Shropshire Canal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Shropshire Canal |

|

|---|---|

The Shropshire Canal at Coalport

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Locks | 0 (3 inclined planes) |

| Status | defunct |

| History | |

| Principal engineer | William Reynolds |

| Date of act | 1788 |

| Date completed | 1791 |

| Date closed | 1912 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Old Yard Junction |

| End point | Coalport |

| Connects to | Donnington Wood Canal, Ketley Canal, Wombridge Canal |

The Shropshire Canal was a special waterway built in Shropshire, England. It was designed to move important materials like coal, iron ore, and limestone. These materials were needed for the factories and industries near the River Severn at Coalbrookdale.

The canal started by connecting to the Donnington Wood Canal. Boats then went up a long slope called the Wrockwardine Wood inclined plane. At the top, it met the older Ketley Canal. A branch of the canal also went to Brierly Hill. The main canal then went down two more inclined planes: the Windmill Incline and the Hay Inclined Plane. It ended at Coalport on the River Severn. The short part of the canal near the River Severn is sometimes called the Coalport Canal.

The Shropshire Canal was finished in 1792 and worked well for many years. Engineers from Prussia even visited in the 1820s to study the Hay inclined plane. In the 1840s, another canal company, the Shropshire Union Canal, leased it. However, the canal started having problems with the ground sinking. After several breaks in its banks in 1855 and 1856, a railway company bought it in 1857. Most of the canal closed in 1858. Parts of it were even turned into a railway line. A small section at the end kept working until 1912. Today, the Hay inclined plane and a part of the canal are looked after by the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust.

Contents

Building the Canal

William Reynolds was a smart and creative ironmaster. He was born in 1758 and learned about iron making at the Coalbrookdale ironworks. He was very interested in science and engineering. In 1783, he started a new ironworks with his brother-in-law.

Reynolds had already helped build the Wombridge Canal and the Ketley Canal (which had an inclined plane) by 1788. He then wanted to build a canal from the Donnington Wood Canal to the River Severn. He got help from his father, John Wilkinson (another ironmaster), and Granville Leveson-Gower (a powerful lord). They all invested money in the project.

On June 11, 1788, a special law was passed by Parliament to create the "Company of Proprietors of the Shropshire Navigation." This company was in charge of building and running the canal. They raised a lot of money for the project.

Reynolds had already planned the canal's route. He likely got help from a civil engineer named William Jessop. The company even held a competition to find the best way to move boats up and down the canal's hills. They offered a prize for the best design.

Work on the canal moved quickly. The first section was finished in early 1789. By 1790, parts of the canal were open, and they started collecting tolls (money for using the canal). The Wrockwardine Wood inclined plane was working soon after. Most of the main canal was ready by 1791, and the whole project was completed by the end of 1792.

At the bottom of the Hay inclined plane, a flat section of canal ran next to the river. There was a lock to the river at first, but it wasn't very useful. The special boats used on the canal couldn't go on the river, and river boats couldn't use the canal. So, the lock was soon filled in. Warehouses were built to move goods between the canal and the river.

When finished, the main canal was about 12.5 kilometers (7.75 miles) long. There was also a branch to Horsehay, which opened in 1792 and was about 4.4 kilometers (2.75 miles) long. The whole project cost less than expected. Even though there were no traditional locks, water was still lost, so several reservoirs were built to keep the canal full.

How the Canal Worked

The Shropshire Canal had three tunnels and three inclined planes. The Snedshill Tunnel was 279 meters (279 yards) long, and the Stirchley Tunnel was 257 meters (281 yards) long. There was also a short tunnel under a main road. The tunnels were about 3 meters (10 feet) wide at water level and 4 meters (13 feet) high. The canal itself was wider, about 5 meters (16 feet) wide and 1.4 meters (4.5 feet) deep.

Instead of traditional locks, which lose a lot of water, Reynolds used inclined planes. These were like ramps where boats were pulled up or down. His design was special because it hardly lost any water. Each inclined plane needed a steam engine to help move the boats.

- The Wrockwardine Wood inclined plane was 360 meters (360 yards) long and lifted boats 36.5 meters (120 feet) up.

- The Windmill inclined plane was 600 meters (600 yards) long and lowered boats 38.4 meters (126 feet).

- The Hay Inclined Plane was the steepest, dropping 63 meters (207 feet) over 350 meters (350 yards).

At first, horses helped move boats on some inclines until the steam engines were ready in 1793. The canal connected to the Ketley Canal at Oakengates. There was a small difference in water levels, so a lock was needed there.

The canal company was run by business owners who wanted to keep the prices low for transporting goods. Even so, the canal made good money, and dividends (payments to shareholders) steadily increased. The end point at Coalport grew quickly, with houses, potteries, and factories. By 1810, they even built a new basin for 60 boats. It's thought that about 100,000 tons of cargo, mostly coal and iron, moved through the canal each year during its busiest times.

Inclined Plane Details

In the 1820s, two engineers from Prussia visited Britain to study railways. They wrote in detail about how the Hay inclined plane worked. The rails were made of strong cast iron. Most of the incline had only three rails, but a short section in the middle had four. This allowed boats going up and down to pass each other.

The boats were made of wood and were about 5.5 meters (18 feet) long and 1.5 meters (5 feet 2 inches) wide. They were 0.76 meters (2.5 feet) deep and weighed about 1.5 tons. When loaded with 5 tons of coal or iron, only a tiny bit of the boat (3 inches) was above the water. To move them on the incline, boats were put on a special wheeled frame.

These inclined planes were quite rare at the time, so many people came to see them. Each incline needed four workers to operate it. Between the inclines, boats were pulled in groups. One horse could pull 12 loaded boats, carrying 60 tons of cargo! Sometimes, groups of 18 or 20 boats were pulled together.

Decline and Closure

In 1845, a railway company called the Ellesmere and Chester Canal Company started planning to turn canals into railways. The next year, this company became the Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Company. This new company was allowed to take over the Shropshire Canal. In 1847, the Shropshire Union Company agreed to be leased by the London and North Western Railway Company (LNWR). This meant the Shropshire Union lost its independence, but it still managed the canals.

The Shropshire Canal was valued at £75,000. Instead of buying it, the Shropshire Union decided to lease it for £3,125 a year, starting in 1849. However, the canal soon faced serious problems with the ground sinking. In 1855, the canal broke through into a railway tunnel, emptying the summit level and causing floods. Seven more breaks happened the next year.

Because of these problems, the LNWR got permission in 1857 to buy the canal for £62,500. They closed most of it on June 1, 1858, and used parts of the canal bed to build a railway to Coalport, which opened in 1861. The Stirchley tunnel was even turned into an open cutting for the railway.

By 1894, the Hay incline was no longer used. However, a section of the canal was still used to carry coal to the Blists Hill furnaces until 1912. In 1905, over 29,000 tons of coal were carried. The furnaces closed in 1912, but this part of the canal wasn't officially abandoned until 1944.

Canal Route

From Wrockwardine to Coalport, the canal generally went south. After connecting to the Donnington Wood Canal, it immediately went up the Wrockwardine incline. At the top was a basin and a wharf (a place for loading and unloading boats). The canal then went under a road that was once part of the Roman Watling Street and entered Snedshill Tunnel.

Further south, the Stirchley Furnaces were on the east side of the canal. The Bishtons owned Langley Furnaces, which were connected to the canal by a tramway. There was also another reservoir before the canal reached Stirchley Tunnel. Beyond this tunnel, the canal split.

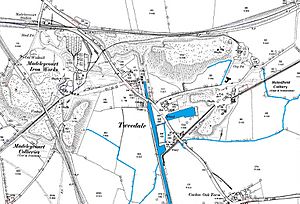

The main route to Coalport turned east, then south again. Here were boat repair sheds and the top of the Windmill incline. Below this incline, the canal went under another road and into Tweedale Basin. Tramways connected this basin to nearby furnaces and collieries (coal mines). These collieries also supplied water to the canal.

The village of Madeley was to the west of the canal. There were also factories and mills along the route, like a cement mill and a corn mill. Shawfield Colliery was on the east bank, and a tramway from it crossed the canal to reach Blist's Hill Brickworks. Blists Hill was a very busy area with boat building, brickworks, and the Blist's Hill Furnaces. Another tramway brought coal from Meadow Pit to Blists Hill. The Hay inclined plane was the steepest, dropping down to a short section of canal that ran next to the River Severn. Here, goods were moved from canal boats to river boats.

Horsehay Branch

Right after the split near Stirchley Tunnel, the canal crossed over a road on an aqueduct (a bridge for water). It then curved northwest. Dawley Castle Furnaces and Botany Bay Colliery were near this branch. The canal followed the land's shape to a point near Doseley church. A tramway went north to Horsehay Furnaces, and the canal then turned sharply south.

Two bridges carried Holywell Lane and Green Lane over the canal before it reached the "Wind." This was the name for two shafts that went down 36.5 meters (120 feet) to the Coalbrookdale Works. After only two years, these shafts were replaced by an inclined plane that used tramway wagons instead of boat cradles.

Canal's Lasting Impact

Parts of the Shropshire Canal are now historical points on the South Telford Heritage Trail. This is a 19.6-kilometer (12.2-mile) walking route that explores the area's industrial past. Much of the canal's original path has been covered by new houses and factories in the town of Telford. However, some larger parts of the canal still remain.

You can still trace the path of the Wrockwardine Wood inclined plane, even though a new road cuts through it. Both tunnels are gone, and a main road (the A442) now covers where the Horsehay branch joined. An aqueduct that carried the canal over a small road near Aqueduct village is a listed building, meaning it's protected for its historical importance.

The remains of the Brierley Hill tunnel and its vertical shafts were found again in 1988. Nearby, parts of the inclined plane that replaced the shafts can still be seen. Nearly 1.6 kilometers (1 mile) of the main canal line above the Hay inclined plane can be traced. It's full of weeds, but some water is still there.

The Hay inclined plane, which was last used in 1894, was restored in 1968 and again in 1975. Its rails were put back in place. At the top of the incline, you can see the remains of a building with a chimney, which was probably the engine house. A historic bridge carries a road over the bottom of the plane.

In 1967, the Dawley Development Corporation decided to save and restore important industrial sites in the area. This led to the creation of the Blists Hill Open Air Museum, which opened in 1973 and is now known as the Blists Hill Victorian Town.

Points of Interest

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wrockwardine Wood inclined plane | 52°42′26″N 2°26′30″W / 52.7071°N 2.4418°W | SJ702122 | |

| Snedshill Tunnel | 52°41′24″N 2°26′46″W / 52.6900°N 2.4460°W | SJ699103 | |

| Stirchley Tunnel | 52°39′14″N 2°27′06″W / 52.6540°N 2.4516°W | SJ695063 | |

| Brierley Hill tunnel and shafts | 52°38′38″N 2°29′13″W / 52.6440°N 2.4869°W | SJ671052 | |

| Aqueduct | 52°39′01″N 2°27′11″W / 52.6504°N 2.4530°W | SJ694059 | |

| Windmill inclined plane | 52°38′46″N 2°26′33″W / 52.6460°N 2.4426°W | SJ701054 | |

| Top of Hay inclined plane | 52°37′21″N 2°27′05″W / 52.6225°N 2.4515°W | SJ695028 | |

| Bottom of Hay inclined plane | 52°37′13″N 2°27′12″W / 52.6202°N 2.4532°W | SJ694025 | |

| End of Coalport wharf | 52°37′01″N 2°26′41″W / 52.6169°N 2.4446°W | SJ699022 |

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |