Siege of Béxar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Béxar |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Texas Revolution | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Texian Rebels | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Martín Perfecto de Cos Domingo Ugartechea Francisco de Castañeda |

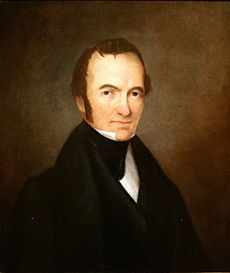

Stephen F. Austin Thomas J. Rusk Edward Burleson Ben Milam † Frank W. Johnson |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,200 | 600 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 150 killed, wounded & captured | 35 killed, wounded & captured | ||||||

The Siege of Béxar (also spelled Béjar) was an important early battle in the Texas Revolution. It took place in what is now San Antonio, Texas. A group of volunteer Texian soldiers fought and defeated the Mexican army there.

Texians were unhappy with the Mexican government. President and General Antonio López de Santa Anna was becoming a very strict ruler. In October 1835, Texas settlers gathered in Gonzales. They wanted to stop Mexican troops from taking back a small cannon. This fight, called the Battle of Gonzales, started the Texas Revolution. More men joined in Gonzales and formed the Texian Army. Even though they had no military training, Stephen F. Austin, a respected local leader, was chosen to lead them.

Santa Anna had sent his brother-in-law, General Martín Perfecto de Cos, to Béxar with more soldiers. On October 13, Austin led his army towards Béxar to face the Mexican troops. The Texians then began a siege of the city. This meant they surrounded the city to try and force the Mexican army to surrender.

Contents

Why the Fight Started

In 1835, people in several Mexican states rebelled. They were unhappy with President Antonio López de Santa Anna's government. He was making the government more "centralist." This meant he wanted all power to be in one central place.

Texians had a small protest about taxes in June. Soon, settlers started forming groups to protect themselves. Mexican officials blamed settlers from the United States for the problems. Many new settlers had not gotten used to Mexican traditions.

Domingo Ugartechea, a military leader in San Antonio de Béxar, sent 100 soldiers. They were led by Francisco de Castañeda. Their job was to get back a small cannon given to the people of Gonzales. The Texians were angry and asked other towns for help. For several days, the Texians delayed the Mexican troops. More Texian fighters arrived.

On October 2, the Texians attacked the Mexican force. Castañeda had orders to avoid a big fight. So, he and his men left. This Battle of Gonzales is seen as the start of the Texas Revolution. After this, a small group of Texians went to Goliad. At the Battle of Goliad, they drove out the small Mexican army at Presidio La Bahia.

Santa Anna worried that stronger actions were needed. He ordered General Martín Perfecto de Cos to lead a large army into Texas. When Cos arrived in San Antonio on October 9, he had 647 soldiers. When Goliad fell to the Texians, Cos lost his way to get supplies from the coast. He believed the Texians would attack San Antonio soon. So, he decided to defend the city instead of attacking the Texian army.

Two days after the Gonzales victory, Stephen F. Austin sent a message. He said, "War is declared." He believed the people wanted to fight against a "Military despotism." Austin wrote that the goal was "to take Béxar, and drive the military out of Texas."

Settlers kept gathering in Gonzales. On October 11, they all chose Austin as their commander. Austin was the first "empresario." This meant he was allowed to bring Anglo settlers into Texas. He had no official military training. But he was respected for his good judgment. He had also led groups against Native American raids.

Austin's first order was for his men to be ready to march. They practiced firing and moving in lines. Austin told them not to shoot their weapons without reason. He also told them to keep their weapons in good shape. He reminded them that "patriotism and firmness" needed "discipline and strict obedience." He said, "The first duty of a soldier is obedience." He also banned "riotous conduct and noisy clamorous talk."

Austin also held elections for army officers. John H. Moore, who led at Gonzales, became a colonel. Edward Burleson, a former officer, became lieutenant colonel. Brazoria merchant Alexander Somervell was elected major.

On October 12, the Texian army had about 300 men. Most were from Austin's settlements. About half had lived in Texas for a long time. The others were newer arrivals. Some had military experience from the United States. Others had joined groups in Texas to fight Native American raids. Almost all were good with guns because they hunted for food.

The men crossed the Guadalupe River that morning. They waited for more help from Nacogdoches. On October 13, Austin led the Texian Army towards San Antonio de Béxar. This was where the last large group of Mexican soldiers was in Texas. Some Texians had no weapons. Those who did had little gunpowder or bullets. As the army marched, Ben Milam formed a small group on horseback to scout ahead. On October 15, one scouting group had a small fight. It was with ten Mexican cavalry soldiers. No one was hurt, and the Mexican soldiers went back to Béxar.

The Texians reached Cibolo Creek on October 16. This was a few miles east of Béxar. Austin asked to meet with Cos. But Cos refused to meet with someone he called an "illegal force." A Texian war meeting decided to stay put and wait for more help. The next day, they changed their minds. Austin moved his army to Salado Creek, about 5 miles (8 km) from Béxar.

Over the next few days, more soldiers and supplies arrived. They came from different English-speaking settlements. One new group, led by James C. Neill, brought two new cannons. These additions brought the Texian army to 453 men. But only about 384 were ready to fight. On October 24, Austin wrote that he had "commenced the investment of San Antonio." He believed the town could be taken in days with more help.

Meanwhile, Cos worked to make the town squares in San Antonio stronger. He also strengthened the walls of the Alamo. The Alamo was a mission that had become a fort near the town. By October 26, Cos's men had 11 cannons ready. Five were in the town squares and six on the Alamo walls. A large 18-pounder cannon was inside the Alamo chapel. It could shoot much farther than the other Mexican cannons.

More Mexican soldiers arrived in Béxar. On October 24, the Mexican army had its highest number: 751 men. Mexican soldiers tried to stop people from entering or leaving the city. But James Bowie was able to leave his home and join the Texians. Bowie was famous for his fighting skills. Stories about his adventures were well known. Juan Seguin, a government official from San Antonio, arrived with 37 Tejanos (Texans of Mexican heritage) on October 22. Later that day, 76 more men joined the Texian Army. They came from Victoria, Goliad, and ranches south of Béxar. The presence of Tejanos showed that the fight was not just between American settlers and Mexicans.

The Siege Begins

First Skirmishes

Even with more men, Austin knew his army was not big enough to attack Béxar directly. So, the Texians got ready for a siege. They looked for a good spot near Béxar. It needed to be easy to defend and block enemy messages. On October 22, Austin made Bowie and Captain James Fannin co-commanders of the 1st Battalion. He sent them to scout the area. By the end of the day, the Texians had taken the Espada mission from Mexican guards. On October 24, Austin said he had started the siege. He thought the city could be taken in a few days if more Texian soldiers arrived fast.

Austin sent Bowie and Fannin to find another good defensive spot on October 27. Instead of returning right away, Bowie and Fannin sent a messenger. They told Austin where they had camped. It was at the old Mission Concepción. This camp was about 2 miles (3 km) from San Antonio de Béxar. It was 6 miles (10 km) from the Texian camp at Espada. Austin was angry. He feared his army would be easily defeated now that it was split. He said officers who did not follow orders would face a military trial. He ordered the army to be ready to join Bowie and Fannin at dawn.

Cos hoped to defeat the Texian force at Concepción before the rest of the Texian Army arrived. So, he ordered Colonel Domingo Ugartechea to attack them early on October 29. The Texians had a good defensive spot, surrounded by trees. This meant the Mexican cavalry could not move easily. The Mexican soldiers soon found their guns were not as good. Their muskets could only shoot about 70 yards (64 m). The Texian long rifles could shoot up to 200 yards (180 m).

The Texians were low on ammunition. Mexican ammunition was plentiful but not good quality. In some cases, Mexican musket balls bounced off Texian soldiers. They caused only bruises. The Battle of Concepción lasted only 30 minutes. Then the Mexican soldiers went back towards Béxar.

Less than 30 minutes after the battle, the rest of the Texian Army arrived. Austin felt the Mexican soldiers must be sad after their defeat. He wanted to go to Béxar right away. But Bowie and other officers refused. They thought Béxar was too strong. The Texians searched the area for any Mexican equipment left behind. They found several boxes of cartridges. The Texians complained that the Mexican gunpowder was "little better than pounded charcoal." So, they emptied the cartridges but kept the bullets. One Texian, Richard Andrews, died. One was wounded. Estimates of Mexican dead range from 14 to 76.

On November 1, Austin sent a note to Cos. He suggested the Mexican army surrender. Cos sent the note back unopened. He said he would not talk with rebels. Austin sent men to check the city's edges. He found that the defenses inside the city were stronger than the Texians thought. On November 2, Austin held a war meeting. They voted to continue the siege. They would wait for more soldiers and cannons before attacking.

Members of the Texian army were eager to fight. Austin complained to the provisional government on November 4. He said his army was "undisciplined militia." He also strongly asked them to "send no more ardent spirits to this camp!" (meaning alcohol).

More Troops Arrive

The siege continued. Soon, more soldiers arrived with Thomas J. Rusk. This brought the Texian army to 600 men. Cos also got more soldiers, bringing the Mexican army to 1,200. This made the Texians even less likely to attack the city directly.

Sam Houston arrived in San Felipe. He expected to meet with the Consultation government. But many members were fighting in the siege of Béxar. So, Houston went to the Texian army outside San Antonio. When Houston arrived, Austin offered him command of the army. But Houston said no. He went ahead to gather the Consultation members.

The members left the army for the meeting (except Austin and William B. Travis). They went back to San Felipe. There, the delegates agreed to fight for the Constitution of 1824. They did not fight for Texas' independence yet. Houston was named general-in-chief of all Texas forces. But this did not include those fighting around San Antonio. Stephen Austin was allowed to go to the U.S. to get support. Edward Burleson, who was Austin's second-in-command, was chosen to lead the volunteer army.

The Grass Fight

The Texian soldiers were not professional soldiers. By early November, many missed their homes. The weather got colder, and food ran low. Many soldiers became sick. Groups of men started to leave, often without permission.

On November 18, a group of volunteers from the United States joined the Texian Army. They were called the New Orleans Greys. Unlike most Texian volunteers, the Greys looked like soldiers. They had uniforms, good rifles, enough ammunition, and some discipline. The Greys, and some Texian groups who had just arrived, wanted to fight the Mexican Army directly.

Encouraged by their excitement, Austin ordered an attack on Béxar for November 22. But several of his officers asked the soldiers that evening. They found that fewer than 100 men wanted to attack Béxar. So, Austin canceled his orders. Within days, Austin left his command to go to the United States. Texians chose Burleson as their new leader.

On the morning of November 26, Texian scout Erastus "Deaf" Smith rode into camp. He reported that a group of mules and horses was near Béxar. About 50 to 100 Mexican soldiers were with them. For several days, Texians had heard rumors. They thought the Mexican Army was getting a shipment of silver and gold. This money was to pay the troops and buy supplies. The Texians had been fighting without pay. Most wanted to attack and take the riches.

Burleson told Bowie to check it out. But he warned him not to attack unless needed. Bowie chose the army's 12 best shooters for the trip. It was clear he planned to find a reason to attack. Burleson stopped the whole army from following. He sent Colonel William Jack with 100 foot soldiers to support Bowie's men.

About 1 mile (1.6 km) from Béxar, Bowie and his men saw the Mexican soldiers. They were crossing a dry ditch. This was likely near where the Alazán, Apache, and San Pedro Creeks meet. After a short fight, the Mexican soldiers went back towards Béxar. They left their pack animals behind.

To the Texians' surprise, the bags on the animals did not have gold. They had freshly cut grass. This grass was to feed the Mexican horses stuck in Béxar. Four Texians were wounded in the fight. One soldier left during the battle. Estimates of Mexican casualties ranged from 3 to 60 killed and 7 to 14 wounded. This victory made the Texians believe they could win against the Mexican army, even if they were outnumbered. The Texians thought Cos must have been desperate to send troops outside the safe walls of Béxar.

The Main Battle

The Attack Begins

Texian spirits began to drop a lot. Winter was coming, and supplies were low. Burleson thought about pulling back into winter camps. In a war meeting, Burleson's officers disagreed. They voted to stay. So, the army remained.

One officer who strongly opposed leaving was Colonel Ben Milam. He walked into the Texian camp and shouted, "Who will go with old Ben Milam into San Antonio?" Three hundred soldiers cheered and said they would go with Milam.

Reports from a captured Mexican soldier and escaped Texian prisoners showed that Mexican morale was also low. Burleson ordered a two-part attack. Milam's troops would attack one way. Colonel Francis W. Johnson's troops would attack another.

On December 5, Milam and Johnson launched a surprise attack. They took two houses in the Military Plaza. One house belonged to Jim Bowie's family. The Texians could not go any further that day. But they made the houses stronger. They stayed there overnight, digging trenches and tearing down nearby buildings.

On December 7, the attack continued. Milam's force captured another spot in the city. However, Milam was killed while leading the attack. Colonel Johnson then took command of both his and Milam's men. He continued the street fighting. They slowly pushed the Mexicans back into the city. Cos pulled back into the Alamo. He was joined by Colonel Ugartechea and 600 more soldiers. But it was too late. Cos made his position stronger. Texian cannons fired at the fortified mission.

As the Texians got closer to the plazas, Cos realized his best defense was inside the Alamo Mission. It was just outside Béxar. In his report to Santa Anna, Cos wrote that he had to move to the Alamo. He said it was smaller and easier to defend. He took the cannons and supplies he could carry. At 1 AM on December 9, the cavalry started to move back towards the Alamo. Colonel Nicolas Condell and his 50 men stayed as a rear guard at the plaza. Years later, some said Cos was not planning to leave the town. He just wanted to move the wounded to the safer Alamo.

Inside the Alamo, Cos suggested a counterattack. But cavalry officers believed they would be surrounded by Texians. They refused their orders. About 175 soldiers from four cavalry groups left the mission. They rode south. Some believed Cos might have been killed when he ran after them. Others said the troops misunderstood their orders and were going all the way to the Rio Grande.

Mexican Surrender

By daylight, only 120 experienced foot soldiers were left in the Mexican army. Cos called Sanchez Navarro to the Alamo. He told him to "go save those brave men." He said to "approach the enemy and obtain the best terms possible." Sanchez Navarro first went back to his post at the plaza. He told the soldiers about the coming surrender. Several officers argued with him. They said, "the Morelos Battalion has never surrendered." But Sanchez Navarro stuck to his orders.

Bugle calls for a talk received no answer from the Texians. At 7 AM, Sanchez Navarro raised a white flag.

Father de la Garza and William Cooke came forward. They took Sanchez Navarro and two other officers to Johnson. Johnson called Burleson. When Burleson arrived two hours later, he found that the Mexican soldiers did not have written permission from Cos. One Mexican officer was sent to get formal permission for the surrender. Burleson agreed to stop fighting right away. Negotiations began. Johnson, Morris, and James Swisher represented the Texians. José Miguel de Arciniega and John Cameron were the interpreters. The men argued for most of the day. They finally agreed on terms at 2 AM on December 10.

Under the agreement, Mexican troops could stay in the Alamo for six days. This was to get ready for their trip back to Mexico. During that time, Mexican and Texian troops were not to carry weapons if they met. Regular soldiers who had ties to the area could stay in Béxar. All recently arrived troops had to return to Mexico.

Each Mexican soldier would get a musket and ten rounds of ammunition. The Texians would allow one small cannon and ten rounds of powder and shot to go with the troops. All other weapons and supplies would stay with the Texians. The Texians agreed to sell some food to the Mexicans for their journey. As the final part of their agreement, all of Cos's men had to promise they would not fight against the Constitution of 1824.

At 10 AM on December 11, the Texian army had a parade. Johnson presented the surrender terms. He asked for the army's approval. He stressed that the Texians had little ammunition left to keep fighting. Most Texians voted for the surrender. But some called it a "child's bargain," meaning it was too weak.

What Happened Next

The Siege of Béxar was the longest Texian campaign of the Texas Revolution. It was the only big Texian success besides the Battle of San Jacinto. The Battle of San Jacinto later led to Texas winning its independence.

Of the 780 Texians who fought, between 30 and 35 were wounded. Five or six were killed. Historian Stephen Hardin says Texian casualties were slightly lower: 4 killed and 14 wounded. The losses were spread evenly between Texas residents and new arrivals from the United States.

Some Texians thought as many as 300 Mexican soldiers were killed. But historians agree that about 150 Mexican soldiers were killed or wounded. This was during the five-day battle. About two-thirds of the Mexican casualties were from the foot soldiers defending the plazas.

To celebrate their victory, Texian troops had a party on the evening of December 10. Governor Henry Smith and the governing council sent a letter to the army. They called the soldiers "invincible" and "brave sons of Washington and freedom." After the war, those who proved they fought in this campaign received 320 acres (130 ha) of land. Eventually, 504 claims were approved.

At least 79 of the Texians who fought later died at the Battle of the Alamo or the Goliad Massacre. Ninety participated in the final battle of the Texas Revolution, at San Jacinto. The Texians took 400 small arms, 20 cannons, and supplies, uniforms, and equipment. During the siege, Cos's men had made the Alamo mission stronger. The Texians chose to gather their forces inside the Alamo instead of making the plazas stronger.

Cos left Béxar on December 14 with 800 men. Soldiers who were too weak to travel were left with Texian doctors. With his departure, there were no more organized Mexican troops in Texas. Many Texians believed the war was over. Johnson called the battle "the period put to our present war." Burleson resigned his leadership on December 15 and went home. Many men did the same. Johnson took command of the soldiers who stayed.

Soon after, new Texian soldiers and volunteers from the United States arrived. They brought more heavy cannons. The large number of American volunteers made Mexicans believe that Texian opposition came from outside influences. This belief may have led to Santa Anna's order to show no mercy in his 1836 campaign.

Santa Anna was furious that Cos had surrendered. He was already getting a larger army ready for Texas. Santa Anna moved quickly when he heard of his brother-in-law's defeat. By late December 1835, he began moving his army north. Many of his officers disagreed with his decision to march inland. They thought a coastal approach was better. But Santa Anna was determined to take Béxar first and get revenge for his family's honor.

See also

In Spanish: Sitio de Béjar para niños

In Spanish: Sitio de Béjar para niños