Alamo Mission facts for kids

The chapel of the Alamo Mission is known as the "Shrine of Texas Liberty"

|

|

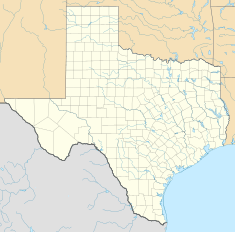

| Location | 300 Alamo Plaza San Antonio, Texas U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 29°25′33″N 98°29′10″W / 29.42583°N 98.48611°W |

| Name as founded | Misión San Antonio de Valero |

| English translation | Saint Anthony of Valero Mission |

| Patron | Anthony of Padua |

| Founding priest(s) | Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivare |

| Area | 5 acres (2.0 ha) |

| Built | 1718 |

| Native tribe(s) Spanish name(s) |

Coahuiltecans |

| Governing body | Texas General Land Office |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii) |

| Designated | 2015 (39th session) |

| Part of | San Antonio Missions |

| Reference no. | 1466-005 |

| State Party | |

| Designated | October 15, 1966 |

| Reference no. | 66000808 |

| Designated | December 19, 1960 |

|

U.S. Historic district

Contributing property |

|

| Designated | July 13, 1977 |

| Part of | Alamo Plaza Historic District |

| Reference no. | 77001425 |

| Designated | June 28, 1983 |

| Reference no. | 8200001755 |

The Alamo is a famous historic building in San Antonio, Texas, USA. It started as a Spanish mission in the 1700s, built by Catholic missionaries. Later, it became a fortress. It was the site of the famous Battle of the Alamo in 1836. This battle was a very important part of the Texas Revolution, where brave American heroes like James Bowie and Davy Crockett fought and died.

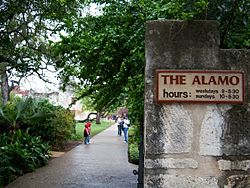

Today, the Alamo is a museum. It is part of the Alamo Plaza Historic District and the San Antonio Missions World Heritage Site.

The mission was first called Misión San Antonio de Valero. It was one of the first Spanish missions in Texas. Its goal was to teach Native American tribes about Christianity. In 1793, the mission stopped being a church and was left empty. Ten years later, it became a fort for a military group called the Second Flying Company of San Carlos de Parras. They probably gave it the name Alamo, which means "cottonwood trees" in Spanish.

During the Texas Revolution, Mexican General Martín Perfecto de Cos gave up the fort to the Texian Army in December 1835. This happened after a long fight called the Siege of Béxar. A small group of Texian soldiers then stayed at the fort for several months. On March 6, 1836, all the defenders were killed in the Battle of the Alamo. When the Mexican Army left Texas later that year, they tore down many of the Alamo's walls and burned some buildings.

For the next five years, soldiers from both Texas and Mexico sometimes used the Alamo. But eventually, it was left empty again. In 1849, after Texas joined the United States, the U.S. Army rented the Alamo. They used it as a supply depot. They left it in 1876 when Fort Sam Houston was built nearby. The Alamo chapel was sold to the state of Texas. It was used for tours, but no one tried to fix it up. The other buildings were sold to a company that used them as a grocery store.

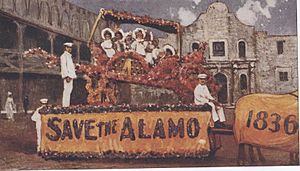

The Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT) group started in 1891. They wanted to save the Alamo. Adina Emilia De Zavala and Clara Driscoll worked hard to convince the state government to buy the remaining buildings in 1905. The DRT was then put in charge of taking care of the Alamo. Over the next 100 years, there were attempts to change who controlled the Alamo. In early 2015, George P. Bush, the Texas Land Commissioner, officially moved control of the Alamo to the Texas General Land Office. On July 5, 2015, the Alamo and four other missions in San Antonio became a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Contents

The Alamo's Story

How the Mission Began

In 1716, the Spanish government set up several Roman Catholic missions in East Texas. These missions were far away from other Spanish towns, making it hard to get supplies. To help the missionaries, the new governor of Spanish Texas, Martín de Alarcón, wanted to create a stopover point. This stopover would be between the settlements along the Rio Grande and the new missions in East Texas.

In April 1718, Alarcón led a trip to start a new community in Texas. They built a temporary structure made of mud, brush, and straw near the San Antonio River. This building became the new mission, San Antonio de Valero. It was named after Saint Anthony of Padua and the viceroy of New Spain, the Marquess of Valero. On May 1, Alarcón officially gave the mission to Father Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares. The mission was near a group of Coahuiltecan people. It started with a few Native American converts from another mission. About one mile (two km) north of the mission, Alarcón built a fort called the Presidio San Antonio de Béxar. Close by, he also started the first town in Texas, San Antonio de Béxar, which is now the city of San Antonio.

Within a year, the mission moved to the west side of the river to avoid floods. Over the next few years, other missions were built nearby. In 1724, a hurricane from the Gulf Coast destroyed the mission buildings. So, the mission moved to its current spot. This new location was across the San Antonio River from the town and north of a group of huts called La Villita.

Over many years, the mission grew to cover about three acres. The first strong building was likely a two-story stone house for the priests. Other buildings were made of adobe to house the Native American converts. There was also a workshop for making cloth. By 1744, more than 300 Native American converts lived at San Antonio de Valero. The mission grew most of its own food and made its own clothes. They had 2,000 cattle and 1,300 sheep. Each year, their farms grew up to 2,000 bushels of corn and 100 bushels of beans. They also grew cotton.

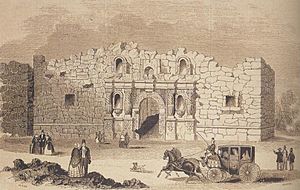

The first stones for a permanent church were laid in 1744. However, the church, its tower, and the sacristy fell down in the late 1750s. Building started again in 1758. The new chapel was at the south end of the inner courtyard. It was made of four-foot-thick limestone blocks. These blocks came from a place where the San Antonio Zoo is now. The church was planned to be three stories high with a dome and bell towers. It was shaped like a cross. The first two levels were finished, but the bell towers and third story were never built. Four stone arches were put up for the dome, but the dome itself was never added. Since the church was never finished, it probably was not used for church services.

The chapel was meant to be very fancy. Niches, or special spaces, were carved on both sides of the door for statues. The lower niches held statues of Saint Francis and Saint Dominic. The upper niches had statues of Saint Clare and Saint Margaret of Cortona. Carvings were also made around the chapel's door.

Up to 30 adobe or mud buildings were built for workshops, storage, and homes for the Native American residents. The nearby fort often did not have enough soldiers. So, the mission was built to protect against attacks by Apache and Comanche raiders. In 1745, 100 mission Native Americans successfully fought off 300 Apaches who had surrounded the fort. Their actions saved the fort, the mission, and likely the town. Walls were built around the Native American homes in 1758. This was probably after a terrible event at the Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá. The convent and church were not fully inside these eight-foot-high walls. The walls were two feet thick. They enclosed an area 480 feet long (north-south) and 160 feet wide (east-west). For more protection, a small tower with three cannons was added near the main gate in 1762. By 1793, another cannon was placed on a wall near the convent.

The number of Native Americans living at the mission changed a lot. It was highest at 328 in 1756 and lowest at 44 in 1777. The new leader of the interior provinces, Teodoro de Croix, thought the missions were a problem. He started to reduce their power. In 1778, he said that all unbranded cattle belonged to the government. Apache tribes had stolen most of the mission's horses. This made it hard to gather and brand the cattle. So, the mission lost a lot of its wealth and could not support many converts. By 1793, only 12 Native Americans remained. By this time, most of the hunting and gathering tribes in Texas had learned about Christianity. In 1793, Misión San Antonio de Valero stopped being a mission.

Soon after, the mission was left empty. Most local people were not interested in the buildings. But visitors were often very impressed. In 1828, a French scientist named Jean Louis Berlandier visited the area. He wrote about the Alamo: "An enormous battlement and some barracks are found there, as well as the ruins of a church which could pass for one of the loveliest monuments of the area."

The Alamo as a Military Fort

In the 1800s, the mission became known as "the Alamo." The name might have come from nearby cottonwood trees, which are called álamo in Spanish. Another idea is that in 1803, a military unit from Álamo de Parras in Coahuila used the empty buildings. Locals often called them simply the "Alamo Company."

During the Mexican War of Independence, parts of the mission were often used as a prison. Between 1806 and 1812, it was San Antonio's first hospital. Spanish records say some repairs were made for this, but no details are given.

The buildings were controlled by Spain, then by Mexico in 1821 after Mexico became independent. Soldiers stayed at the fort until December 1835. That's when General Martín Perfecto de Cos gave up to Texian forces. This happened after a two-month siege of San Antonio de Béxar during the Texas Revolution. In the few months Cos was in charge, he ordered many improvements to the Alamo. His men likely tore down the four stone arches that were supposed to hold a church dome. They used the broken pieces to build a ramp to the back of the chapel. There, Mexican soldiers placed three cannons that could fire over the roofless building's walls. To close a gap between the church and the barracks, the soldiers built a wooden fence. When Cos left, he left behind 19 cannons.

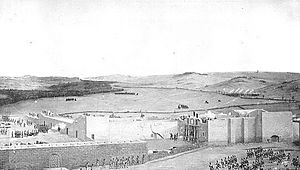

The Battle of the Alamo

After General Cos left, there were no organized Mexican troops in Texas. Many Texians thought the war was over. Colonel James C. Neill took command of the 100 soldiers who stayed. Neill asked for 200 more men to make the Alamo stronger. He worried his small group could be starved out after a four-day siege. However, the Texian government was having problems and could not send much help. Neill and engineer Green B. Jameson started to make the Alamo stronger. Jameson put the cannons that Cos had left along the walls.

General Sam Houston heard Neill's warnings. He ordered Colonel James Bowie to take 35–50 men to Béxar. Their job was to help Neill move all the cannons and destroy the fort. But there were not enough oxen to move the cannons to a safer place. Most of the men believed the fort was important for protecting the settlements to the east. On January 26, the Texian soldiers decided to hold the Alamo. On February 11, Neill left to find more soldiers and supplies. William Travis and James Bowie agreed to share command of the Alamo.

On February 23, 1836, the Mexican Army arrived in San Antonio de Béxar. Their leader was President-General Antonio López de Santa Anna. They wanted to take back the city. For the next thirteen days, the Mexican Army surrounded the Alamo in a siege. During this time, work continued inside the fort. Mexican soldiers tried to block the water ditch leading into the fort. So, Jameson oversaw the digging of a well at the south end of the plaza. They found water, but they also weakened a wall near the barracks. This caused it to collapse, making it unsafe to fire over that wall.

The siege ended with a fierce battle on March 6. As the Mexican Army climbed over the walls, most Texians went back to the long barracks and the chapel. During the siege, Texians had carved holes in many of the walls in these rooms so they could shoot. Each room had only one door leading to the courtyard. These doors were protected by dirt walls. Some rooms even had trenches dug into the floor for cover. Mexican soldiers used the Texian cannons they captured to blast open the doors. This allowed them to enter and defeat the Texians.

The last Texians to die were eleven men using two 12-pound cannons in the chapel. The entrance to the church was blocked with sandbags, which the Texians could shoot over. A shot from an 18-pound cannon destroyed the barricades. Mexican soldiers entered the building after firing their muskets. With no time to reload, the Texians, including Dickinson, Gregorio Esparza, and Bonham, grabbed rifles and fired before being killed with bayonets. Texian Robert Evans was in charge of gunpowder. He was supposed to keep it from falling into Mexican hands. Wounded, he crawled toward the powder room but was killed by a musket ball. His torch was only inches from the powder. If he had succeeded, the explosion would have destroyed the church.

Santa Anna ordered the Texian bodies to be piled up and burned. All, or almost all, of the Texian defenders were killed in the battle. Some historians believe at least one Texian, Henry Warnell, escaped. Warnell died several months later from wounds he got during the battle or his escape. Most Alamo historians agree that 400–600 Mexicans were killed or wounded. This was about one-third of the Mexican soldiers in the final attack. Historian Terry Todish said this was "a tremendous casualty rate by any standards."

More Military Use

After the Battle of the Alamo, one thousand Mexican soldiers, led by General Juan Andrade, stayed at the mission. For the next two months, they repaired and strengthened the fort. However, there are no records of what improvements they made. After the Mexican army lost the Battle of San Jacinto and Santa Anna was captured, the Mexican army agreed to leave Texas. This ended the Texas Revolution. As Andrade and his soldiers left on May 24, they disabled the cannons, tore down many Alamo walls, and set fires. Only a few buildings survived. The chapel was in ruins, most of the Long Barracks was still standing, and the building with the south wall gate was mostly whole.

The Texians briefly used the Alamo as a fort in December 1836 and again in January 1839. The Mexican army took control again in March 1841 and September 1842. They briefly took San Antonio de Bexar. Historians Roberts and Olson said, "both groups carved names in the Alamo's walls, dug musket rounds out of the holds, and knocked off stone carvings." Pieces of the debris were sold to tourists. In 1840, the San Antonio town council allowed citizens to take stone from the Alamo for $5 per wagonload. By the late 1840s, even the four statues on the front wall of the chapel had been removed.

On January 13, 1841, the Republic of Texas government passed a law giving the Alamo chapel back to the Roman Catholic Church. By 1845, when Texas joined the United States, bats lived in the empty buildings. Weeds and grass covered many of the walls.

As the Mexican–American War was about to begin in 1846, 2000 United States Army soldiers were sent to San Antonio. They were led by Brigadier General John Wool. By the end of the year, they used part of the Alamo for their Quartermaster's Department (supplies). Within eighteen months, the convent building was repaired and used as offices and storage. The chapel remained empty because the army, the Catholic Church, and the city of San Antonio argued over who owned it. In 1855, the Texas Supreme Court decided that the Catholic Church owned the chapel. While the arguments continued, the army rented the chapel from the Catholic Church for $150 per month.

Under the army's care, the Alamo was greatly repaired. Soldiers cleaned the grounds and rebuilt the old convent and mission walls. They mostly used the original stones that were lying around. During these repairs, a new wooden roof was added to the chapel. A bell-shaped front was also added to the chapel's front wall. At that time, reports said that soldiers found several skeletons while clearing the rubble from the chapel floor. The new chapel roof was destroyed in a fire in 1861. The army also cut more windows into the chapel. They added two on the upper front and more on the other three sides. The complex eventually had a supply depot, offices, storage, a blacksmith shop, and stables.

During the American Civil War, Texas joined the Confederacy. The Confederate Army took over the Alamo. In February 1861, the Texan Militia, led by Ben McCullough and Sam Maverick, faced General Twiggs. Twiggs was the commander of all US Forces in Texas and was based at the Alamo. Twiggs decided to surrender, and all supplies were given to the Texans. After the Confederacy lost the war, the United States Army took control of the Alamo again. Soon after the war, the Catholic Church asked the army to leave. They wanted the Alamo to be a place of worship for local German Catholics. The army refused, and the church did not try to take it back again.

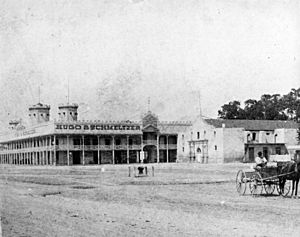

The Alamo as a Store

The army left the Alamo in 1876 when Fort Sam Houston was built in San Antonio. Around that time, the Church sold the convent building to Honore Grenet. He added a new two-story wooden building to the complex. Grenet used the convent and the new building for a wholesale grocery business. After Grenet died in 1882, his business was bought by Hugo & Schmeltzer, who continued to run the store.

San Antonio got its first train service in 1877. The city's tourism started to grow. The city advertised the Alamo a lot. They used photos and drawings that only showed the chapel, not the city around it. Many visitors were disappointed. In 1877, a tourist named Harrier P. Spofford wrote that the chapel was "a reproach to all San Antonio." She said its walls were broken, its rooms were filled with military supplies, and its battle-scarred front had been changed.

Who Owns the Alamo?

In 1883, the Catholic Church sold the chapel to the State of Texas for $20,000. The state hired Tom Rife to manage the building. He gave tours but did not try to fix the chapel, which annoyed many people. In past decades, soldiers and members of the local Masonic lodge had written graffiti on the walls and statues. In May 1887, a Catholic person was arrested. They were angry that Masonic symbols were on a statue of Saint Teresa. They broke into the building and smashed statues with a sledgehammer.

The 50th anniversary of the Alamo's fall did not get much attention. Afterward, the San Antonio Express newspaper called for a new group to recognize important historical events. The Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT) formed in 1892. One of their main goals was to save the Alamo. Adina Emilia De Zavala, whose grandfather was the Vice-president of the Republic of Texas, was an early member. Around 1900, Adina de Zavala convinced Gustav Schmeltzer, who owned the convent building, to offer it to the DRT first if he ever sold it. In 1903, Schmeltzer wanted to sell the building to a developer. He offered it to the DRT for $75,000, but they did not have the money. While De Zavala tried to raise money, she met Clara Driscoll. Clara was a wealthy person who loved Texas history, especially the Alamo.

Soon after, Driscoll joined the DRT. She became the head of the San Antonio chapter's fundraising group. The DRT arranged to have 30 days to buy the property. They would pay $500 upfront, $4,500 after 30 days, and another $20,000 by February 10, 1904. The rest would be paid in five yearly payments of $10,000. Driscoll paid the first $500 from her own money. When fundraising did not get enough money (only $1,021.75 of the $4,500 needed), Driscoll paid the rest herself.

Driscoll and de Zavala urged the Texas government to approve $5,000 for the next payment. But Governor S. W. T. Lanham said no. He said it was "not a justifiable expenditure of the taxpayers' money." DRT members set up a collection booth outside the Alamo and held fundraising events. They collected $5,662.23. Driscoll agreed to pay the difference and the final $50,000. After people heard about her generosity, newspapers called her the "Savior of the Alamo." Many groups asked the government to pay Driscoll back. In January 1905, de Zavala wrote a bill. It was supported by representative Samuel Ealy Johnson Jr. (father of future US President Lyndon Baines Johnson). The bill was to pay Driscoll back and make the DRT the caretakers of the Alamo. The bill passed, and Driscoll got all her money back.

Driscoll and de Zavala argued about how to best preserve the building. De Zavala wanted to make the outside of the buildings look like they did in 1836. She focused on the convent, which was then called the long barracks. Driscoll wanted to tear down the long barracks. She wanted to create a monument like ones she had seen in Europe: "a city center opened by a large plaza and anchored by an ancient chapel."

They could not agree. So, Driscoll and some other women formed a different DRT chapter called the Alamo Mission chapter. The two chapters argued over who was in charge of the Alamo. In February 1908, the DRT executive committee leased out the building. De Zavala was angry. She announced that a group wanted to buy the chapel and tear it down. She then locked herself in the Hugo and Schmeltzer building for three days.

Because of de Zavala's actions, on February 12, Governor Thomas Mitchell Campbell ordered that the superintendent of public buildings take control of the property. Eventually, a judge named Driscoll's chapter the official caretakers of the Alamo. The DRT later removed de Zavala and her followers from the group.

Restoring the Alamo

Driscoll offered to pay to tear down the convent, build a stone wall around the Alamo, and turn the inside into a park. The government delayed a decision until after the 1910 elections. After that, Texas had a new governor, Oscar Branch Colquitt. Both de Zavala and Driscoll spoke to him. Colquitt toured the property. Three months later, Colquitt removed the DRT as official caretakers of the Alamo. He said they had done nothing to restore the property since they took control. He also announced he planned to rebuild the convent. Soon after, the government paid to tear down the building that Hugo and Schmeltzer had added. They also approved $5,000 to restore the rest of the complex. The restorations began but were not finished because the money was not enough.

Driscoll was upset with Colquitt's decisions. She used her influence as a big donor to the Democratic Party to work against him. At the time, Colquitt was thinking about running for U.S. Senate. She told the New York Herald Tribune that "the Daughters desire to have a Spanish garden on the site of the old mission, but the governor will not consider it. Therefore, we are going to fight him from the stump." She also said they would make speeches against senators who voted against giving control back to the DRT. Later, while Colquitt was away, Lieutenant Governor William Harding Mayes allowed the upper walls of the long barracks to be removed. Only the one-story walls of the west and south parts of the building were left. This conflict became known as the Second Battle of the Alamo. When Driscoll died in 1945 and de Zavala in 1955, their bodies were placed in the Alamo Chapel for people to see.

In 1931, Driscoll convinced the state government to buy two pieces of land between the chapel and Crockett street. In 1935, she convinced the city of San Antonio not to put a fire station in a building near the Alamo. The DRT later bought that building and made it the DRT Library. During the Great Depression, money from government programs was used to build a wall around the Alamo and a museum. They also tore down several non-historic buildings on the Alamo property. The Alamo Cenotaph, a monument designed by Pompeo Coppini, was finished in 1940.

The Alamo was named a National Historic Landmark on December 19, 1960. It was also recorded by the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1961. It was one of the first places listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. It is also part of the Alamo Plaza Historic District, which was named in 1977. As San Antonio got ready for the Hemisfair in 1968, the long barracks got a roof and became a museum. Few big changes have happened since then.

According to Herbert Malloy Mason's Spanish Missions of Texas, the Alamo is one of "the finest examples of Spanish ecclesiastical building on the North American continent." However, the mission and other San Antonio missions are at risk from the environment. The limestone used to build them came from the San Antonio River banks. It expands when it gets wet and shrinks when it gets cold. This causes small pieces of limestone to break off. Steps have been taken to help with this problem.

Disputes Over Control

In 1988, a theater near the Alamo showed a new movie, Alamo: The Price of Freedom. The 40-minute film was shown many times a day. The movie caused many protests from Mexican-American activists. They said the movie had anti-Mexican comments and did not show what Tejano people did in the battle. The movie was re-edited because of the complaints. But the argument grew, and many activists started to push the government to move control of the Alamo to the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). Because of pressure from Hispanic groups, state representative Orlando Garcia of San Antonio started hearings about the DRT's money. The DRT agreed to share their financial records more openly, and the hearings were canceled.

Soon after, San Antonio representative Jerry Beauchamp suggested that the Alamo be moved from the DRT to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Many minority lawmakers agreed with him. However, the San Antonio mayor, Henry Cisneros, said control should stay with the DRT. So, the government put the bill aside.

Several years later, Carlos Guerra, a reporter for the San Antonio Express-News, wrote articles criticizing the DRT for how they managed the Alamo. Guerra claimed the DRT kept the chapel too cold. This caused water vapor to form, which mixed with car exhaust fumes and damaged the limestone walls. These claims led the government in 1993 to try again to move control of the Alamo to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. At the same time, State Senator Gregory Luna filed a bill to move oversight of the Alamo to the Texas Historical Commission.

Bones of three adults and a child were found in 1936. A report in 1976 showed that the plaza was on top of a cemetery. Research by San Antonio's county archivist John Leal showed that 1,006 people were buried in the area. 921 of them were Native American or of mixed heritage. State law said nothing could be built on top of cemeteries. Gary Gabehart, president of the Inter-Tribal Council of American Indians, asked for part of the plaza to be closed to traffic in 1994. But the DRT said there was no proof of burials at the Alamo.

By the next year, some groups in San Antonio started pushing for the mission to become a larger historical park. They wanted to make the chapel look like it did in the 1700s. They also wanted to focus on the Alamo's mission days, not just the Texas Revolution. The DRT was very angry. The head of their Alamo Committee, Ana Hartman, said the argument was about gender. She said, "There's something macho about it. Some of the men who are attacking us just resent what has been a successful female venture since 1905."

The dispute was mostly settled in 1994. Governor George W. Bush promised to stop any law that would remove the DRT as caretakers of the Alamo. Later that year, the DRT put up a marker on the mission grounds. It recognized that the area had once been Native American burial grounds. When renovations found more bones, the DRT allowed the Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation to hold reburial ceremonies. Since 1995, the Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation holds a ceremony at the church to honor the buried, except when they were denied entrance in 2019.

In 2006, Sarah Reveley found that the DRT's yearly budget for preserving the Alamo was only $350. She also learned that out of $213,000 given to the group by the state between 2005 and 2008, only $37,000 was spent on the Alamo. The rest went to their museums in Austin. The French Legation Museum received three times what was spent on the Alamo. Reveley filed a 65-page complaint against the DRT in 2009. She said they broke the 1905 law that required the Alamo to be properly maintained. Pieces of the ceiling's plaster in the church fell on February 11, 2009. The DRT removed Revely from the group, which was the fourth time this had happened in its history.

In 2010, the office of the Texas Attorney General received a complaint. It said the DRT had been mismanaging the site and the money given for its care. An investigation began. After two years, the Attorney General's office concluded that the DRT had indeed mismanaged the Alamo. They listed many examples of bad behavior. These included not properly maintaining the Alamo, mismanaging state funds, and not doing their duty.

During the investigation, a state law was passed in 2011. Governor Rick Perry signed it. This law moved the care of the Alamo from the DRT to the Texas General Land Office (GLO). The change officially happened in 2015. The DRT first disagreed with the Attorney General's report. They even filed a lawsuit to stop the transfer. But the organization eventually promised to work with the Texas GLO to preserve the Alamo for future generations.

The Alamo Today

As of 2002, the Alamo welcomed over four million visitors each year. This makes it one of the most popular historic sites in the United States. Visitors can tour the chapel and the Long Barracks. The Long Barracks has a small museum with paintings, weapons, and other items from the Texas Revolution. More items are shown in another building. There is also a large model that shows what the fort looked like in 1836. A big mural, called the Wall of History, shows the Alamo's story from its mission days to modern times.

The site has a yearly budget of $6 million to operate. Most of this money comes from sales in the gift store. Under the 2011 law, the Alamo is cared for by the General Land Office. Commissioner George P. Bush announced on March 12, 2015, that his office would take over the daily operations of the Alamo from the Daughters of the Republic of Texas.

There has been new resistance to the General Land Office's plan for the site. The plan wants to make the site four times bigger and include a 100,000-square-foot museum. One concern is the idea of moving the Alamo Cenotaph to a different place. Other worries include the proposed $450 million cost of the project. People also worry about any changes to the story of the Alamo.

Images for kids

-

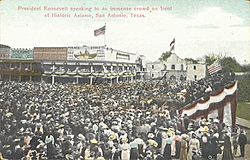

Under six flags, Alamo, San Antonio, Texas (postcard, circa 1915–1924)

-

Memorial poem carved in granite written by a Japanese geography professor in 1914 comparing the Battle to the siege of Nagashino Castle in 1575

See also

In Spanish: Misión de El Álamo (Texas) para niños

In Spanish: Misión de El Álamo (Texas) para niños

- Alamo Village, in Brackettville, Texas

- Espada Acequia, an aqueduct

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Texas

- List of the oldest buildings in Texas

- List of World Heritage Sites in the United States

- Main and Military Plazas Historic District

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Bexar County, Texas

- Spanish Governor's Palace