Coahuiltecan facts for kids

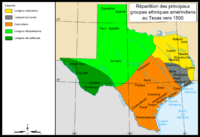

Coahuiltecan territories in the 16th and 17th centuries

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| merged into other groups by 1900 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| San Antonio, South Texas, U.S.; Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, and northeastern Coahuila, Mexico | |

| Languages | |

| Coahuiltecan languages | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous religion, Roman Catholicism |

The Coahuiltecan were many small groups of Native Americans. They lived in what is now southern Texas and northeastern Mexico. These groups were hunter-gatherers, meaning they hunted animals and gathered plants for food.

Europeans first met the Coahuiltecan people in the 1500s. Their population sadly decreased a lot. This was due to new diseases brought by Europeans, people being forced into slavery, and many wars. They fought against the Spanish, Criollo settlers, Apache people, and even other Coahuiltecan groups.

After Texas became separate from Mexico, the Coahuiltecan way of life became very difficult. Because of these hard times, many people today in the United States and Texas do not know much about the Coahuiltecan culture.

In 1886, a scientist named Albert Samuel Gatschet found the last known Coahuiltecan survivors. They were living near Reynosa, Mexico.

Contents

- What Does "Coahuiltecan" Mean?

- Where Did the Coahuiltecan Live?

- A Brief History of the Coahuiltecan

- How Many Coahuiltecan People Were There?

- What Languages Did They Speak?

- How Did They Live and What Were Their Homes Like?

- What Was Their Religion Like?

- Did They Fight Wars?

- What Did the Coahuiltecan Eat?

- See also

What Does "Coahuiltecan" Mean?

The name "Coahuiltecan" comes from Coahuila. This was a state in New Spain where Europeans first met these people. The Spanish got this name from a Nahuatl word.

Where Did the Coahuiltecan Live?

The Coahuiltecan people lived in the flat, dry, and brushy lands of southern Texas. This area was roughly south of a line from the Gulf Coast near the Guadalupe River to San Antonio. It stretched westward to around Del Rio, Texas. They lived on both sides of the Rio Grande river.

Their neighbors included the Karankawa along the Texas coast and the Tonkawa to their northeast. The Jumano lived to their north. Later, the Lipan Apache and Comanche tribes also moved into this area. Their western border was near Monclova, Coahuila and Monterrey, Nuevo Leon. To the south, they lived near Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas.

Even though they lived near the Gulf of Mexico, most Coahuiltecan groups stayed inland. This was because there was not much fresh water near the coast. This limited their ability to live there and use coastal resources like fish and shellfish.

A Brief History of the Coahuiltecan

In the early 1530s, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and his three friends were the first Europeans known to live among the Coahuiltecan. They traveled through their lands.

In 1580, the governor of Nuevo Leon, Carvajal, started regularly raiding Coahuiltecan lands to capture people for slavery. The Coahuiltecan also raided Spanish settlements. They even drove the Spanish out of Nuevo Leon in 1587. But they were not organized enough to defend themselves when more Spanish settlers returned in 1596. Conflicts between the Coahuiltecan and the Spanish continued for many years. The Spanish later made Native Americans move into a system called encomienda instead of slavery.

Diseases like smallpox and measles were common. These diseases caused many deaths among the Native Americans because they had no protection against them. The first recorded outbreak was from 1636 to 1639. More outbreaks followed every few years. One historian from the 1600s said that all Native American groups would soon disappear because of disease. He listed 161 groups that had once lived near Monterrey but were gone.

Spanish explorers kept finding large Coahuiltecan settlements near the Rio Grande delta. They also found big camps with many tribes along the rivers of southern Texas, especially near San Antonio. The Spanish built Mission San Antonio de Valero (which later became the Alamo) in 1718. They wanted to teach Christianity to the Coahuiltecan and other Native Americans, especially the Jumano. Soon, they built four more missions.

The Coahuiltecan people sometimes went to the missions. They sought protection from new dangers like Apache, Comanche, and Wichita raiders from the north. About 1,200 Coahuiltecan and other Native Americans lived in these five missions between 1720 and 1772.

Spanish settlement of the lower Rio Grande Valley began in 1748. This area was where most Coahuiltecan people still lived. In 1757, the Spanish found fourteen different groups living in the delta. Spanish settlers soon outnumbered the Coahuiltecan. Within a few decades, most Coahuiltecan people joined the Spanish and Mestizo populations.

By 1827, only four property owners in San Antonio were listed as "Indians" in the census.

How Many Coahuiltecan People Were There?

Over 300 years of Spanish rule, explorers and priests wrote down the names of more than a thousand groups or bands. The names and makeup of these groups likely changed often. They were often named after places. Most groups probably had between 100 and 500 people.

Experts believe that when the Spanish first arrived, there were about 86,000 to 100,000 non-farming Native Americans in northeastern Mexico and Texas. About 15,000 of these may have lived in the Rio Grande delta, which was a very crowded area. In 1757, a small group of African people, likely escaping slavery, were also recorded living in the delta.

Diseases and slavery greatly reduced the Coahuiltecan population near Monterrey by the mid-1600s. The Coahuiltecan in Texas might have suffered less from diseases and slave raids at first. This was because they were farther away from the main Spanish areas. However, diseases still spread through trade among Native American groups.

After a Franciscan Roman Catholic mission was built in 1718 at San Antonio, the Native American population quickly declined. This was especially true after smallpox outbreaks began in 1739. Most Coahuiltecan groups disappeared before 1825. Their remaining members joined other Native American or mixed-heritage groups in Texas or Mexico.

What Languages Did They Speak?

Most modern language experts believe that the Coahuiltecan people had different cultures and spoke different languages. At least seven different languages are known to have been spoken. One of these is called Coahuiltecan or Pakawa. It was spoken by several groups near San Antonio. The best-known languages are Comecrudo and Cotoname. Both were spoken by people in the Rio Grande delta, along with Pakawa.

How Did They Live and What Were Their Homes Like?

The Coahuiltecan were nomadic hunter-gatherers. This means they moved from place to place to find food. They carried their few belongings on their backs. At each campsite, they built small round huts. These huts had frames made of four bent poles. They covered these frames with woven mats. They wore very little clothing.

Sometimes, many groups would come together in large gatherings. These could include hundreds of people. But most of the time, their camps were small, with just a few huts and a few dozen people. Along the Rio Grande, some Coahuiltecan lived a more settled life. They might have built stronger homes using palm leaves.

Most Coahuiltecan people seemed to follow a regular path as they searched for food. For example, the Payaya group near San Antonio had ten different summer campsites. These were spread out over an area about 30 miles square. Some groups lived near the coast in winter. In the summer, they would travel about 85 miles (140 km) inland. They did this to find prickly pear cactus thickets. Fish was probably the main source of protein for groups living in the Rio Grande delta.

What Was Their Religion Like?

We don't know much about the original religion of the Coahuiltecan people. They sometimes gathered in large numbers for all-night dances called mitotes. During these events, they danced and used peyote as a medicine.

Did They Fight Wars?

The limited resources in their homeland led to strong competition. This often resulted in small-scale warfare between groups.

What Did the Coahuiltecan Eat?

Coahuiltecan people hunted animals for meat. These included deer, bison, peccary (a type of wild pig), armadillos, rabbits, rats, mice, snakes, lizards, frogs, salamanders, and snails. They also fished and caught shellfish. Fish was likely most important for groups living near the Rio Grande delta.

Most foods could be eaten raw. But they used open fires or fire pits for cooking.

Plants made up most of their diet. Pecans were an important source of protein. They gathered pecans in the fall and stored them for later. They cooked the bulbs and root crowns of the maguey, sotol, and lechuguilla plants in pits. They also ground mesquite beans to make flour.

Prickly pear cactus was a very important summer food. They ate its pads (called nopales) and its fruits (called tuna). It also gave them water when water was hard to find. In the winter, plant roots were an important food source.

See also

In Spanish: Coahuiltecos para niños

In Spanish: Coahuiltecos para niños

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |