Siege of Drogheda facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Drogheda (1649) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cromwellian Conquest of Ireland | |||||||

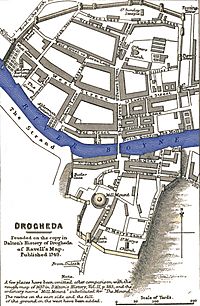

A plan of Drogheda in 1649 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,547 | c. 12,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| c. 2,000 killed, wounded or captured | c. 150 killed or wounded | ||||||

| 700–800 civilians killed | |||||||

The Siege of Drogheda happened from September 3 to 11, 1649. It was a major event at the start of the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland. The town of Drogheda was defended by a mix of Irish Catholics and Royalists. Their leader was Sir Arthur Aston.

English forces, led by Oliver Cromwell, attacked the town. Cromwell was the commander of the Commonwealth of England army. Sir Arthur Aston refused to give up the town. So, Cromwell's soldiers stormed it. Many of the defenders were killed. A number of civilians also died. This event is still seen as a terrible act today. It affects how people view Cromwell.

Contents

Why the Siege Happened

Since 1642, most of Ireland was controlled by the Irish Catholic Confederation. They had taken over much of the country after the 1641 Irish rebellion. In 1649, King Charles I of England was executed. After this, the Irish Confederates joined forces with English Royalists. They wanted to secure Ireland for Charles I's son, Charles II of England.

In June 1649, these combined forces attacked Dublin. But they lost the Battle of Rathmines on August 2. Some Royalist Protestants then switched sides. James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde, had to gather his remaining troops. He needed to form a new army.

Oliver Cromwell landed near Dublin in August 1649. His army was made up of experienced soldiers. Many were from the New Model Army. Cromwell's goal was to take back Ireland for the Commonwealth of England. On August 23, Royalist leaders met in Drogheda. They decided to defend the town.

Drogheda's defense force had about 2,550 men. These were a mix of Royalist and Confederate soldiers. Sir Arthur Aston led them. Ormonde's plan was to avoid big battles. Instead, he wanted to hold towns in eastern Ireland. He hoped that lack of food and sickness would weaken Cromwell's army.

Cromwell needed to capture ports on Ireland's east coast quickly. This was important for getting supplies for his troops. Armies usually fought from spring to autumn. This was when they could find food easily. Cromwell arrived late in the year. So, he needed a constant supply of goods from the sea. He preferred fast attacks on towns using his cannons. This was quicker than long blockades.

The Siege of Drogheda

Cromwell reached Drogheda on September 3. His large cannons arrived by sea two days later. Cromwell's total army had about 12,000 soldiers. They had eleven heavy cannons, each firing 48-pound balls.

Drogheda's defenses were old medieval walls. These walls were tall but not very thick. This made them weak against cannon fire. Most of the town was north of the River Boyne. But its two main gates, Dublin and Duleek, were south of the river. The Millmount Fort also stood south of the river. It overlooked the town's defenses.

Cromwell placed his forces south of the River Boyne. This allowed him to focus his attack. He left the northern side of the town open. A small group of cavalry covered it. Parliamentarian ships also blocked the town's harbor.

Cromwell later explained why he did not surround the whole town. He wrote that dividing his army would make it vulnerable. The defenders could attack one part of his army. They could also launch a surprise attack from inside the town.

Call to Surrender

Cromwell set up his cannons near the Duleek gate. They were on both sides of St Mary's Church. This gave them a good firing position. They made two large holes, called breaches, in the walls. One was south of the church, the other to the east. After this, Cromwell asked the Royalists to surrender.

On Monday, September 10, Cromwell sent a letter to Sir Arthur Aston. It said:

Sir, I have brought the Parliament's army here. I want to bring this place under control. To prevent bloodshed, I ask you to give the town to me. If you refuse, you will have no one but yourself to blame. I await your answer. Your servant, O. Cromwell

The rules of war at that time were clear. If a town refused to surrender and was then captured by force, its defenders could be killed. Accepting a surrender after an attack was up to the attacker.

Aston refused to surrender. His soldiers in Drogheda were very low on gunpowder and ammunition. They hoped that Ormonde, who was nearby with about 4,000 Royalist troops, would come to help them.

The Attack

At 5:00 PM on September 11, Cromwell ordered attacks on both breaches in Drogheda's walls. Three regiments attacked the holes. They gained a foothold in the south. But they were pushed back in the east. Cromwell had to send two more regiments to the eastern attack. The second wave of soldiers climbed over piles of their dead comrades. At the southern breach, the defenders fought back. Their commander, Colonel Wall, was killed. This made them retreat. More Parliamentarian soldiers then poured into the breach. About 150 Parliamentarian troops died in the fighting at the walls. This included Colonel Castle.

After Colonel Wall's death, more and more Parliamentarian soldiers entered the town. The Royalist defense at the walls collapsed. The remaining defenders tried to escape across the River Boyne. They headed to the northern part of the town. Aston and 250 others hid in Millmount Fort. This fort overlooked Drogheda's southern defenses. Other defenders were stuck in towers along the town walls. Meanwhile, Cromwell's troops rushed into the town.

With up to 6,000 Parliamentarian troops now inside, Drogheda was captured.

The Aftermath

When Cromwell rode into the town, he saw many dead Parliamentarian soldiers at the breaches. This made him very angry. He ordered his soldiers not to spare anyone who was armed in the town. That night, about 2,000 men were killed.

After breaking into the town, Cromwell's soldiers chased the defenders. They went through the streets and into private homes. They also attacked churches and other strong points. There was a drawbridge that could have stopped the attackers from reaching the northern part of the town. But the defenders did not have time to pull it up. So, the killing continued in northern Drogheda.

Killing of Prisoners

About 200 Royalists, led by Aston, had barricaded themselves in Millmount Fort. This was while the rest of the town was being taken. A Parliamentarian colonel, Daniel Axtell, offered to spare their lives if they surrendered. They did surrender.

According to Axtell, these disarmed men were then taken to a windmill. They were killed about an hour after they had given up. Aston was reportedly beaten to death. His wooden leg was broken. Parliamentarian soldiers thought he had hidden gold inside it.

Some Royalists, like Aston, were Englishmen. They had been captured and released on parole in England earlier. But they continued fighting for King Charles in Ireland. Cromwell's side believed they had broken their promise. So, they could be executed. The Royalists argued that their parole only applied in England, not in Ireland.

Another group of about 100 Royalist soldiers hid in the steeple of St Peter's Church. This church was at the northern end of Drogheda. Parliamentarian soldiers, led by John Hewson, set fire to the steeple. Cromwell had given this order. About 30 defenders burned to death inside. Another 50 were killed outside when they tried to escape the flames.

The last large group of Royalist soldiers was about 200 men. They had retreated into two towers. One was the west gate, and the other was a round tower called St. Sunday's. They were asked to surrender but refused. So, guards were placed on the towers. The Parliamentarians waited, sure that hunger would make them give up. When the people in the towers finally surrendered, they were treated differently. Those in one tower, about 120 to 140 men, had killed and wounded some guards. All the officers from that tower were killed. Many of the regular soldiers were also killed. The remaining men from the first tower, along with the soldiers in the other tower, were sent away to Barbados.

The heads of 16 Royalist officers were cut off. They were sent to Dublin. There, they were put on spikes along the roads leading into the city. Any Catholic priests found in the town were also killed. Cromwell himself said they were "knocked on the head." This included two who were executed the next day.

Cromwell wrote on September 16, 1649: "I believe we killed all the defenders. I do not think thirty of them escaped alive. Those who did are safely held for Barbados." He listed Royalist losses as 60 officers, 220 cavalry soldiers, and 2,500 infantry.

However, Colonel John Hewson wrote that "those in the towers, about 200, surrendered to the General's mercy. Most of them were spared and sent to Barbados." Other reports mentioned 400 military prisoners. Some of the soldiers escaped over the northern wall. According to one Royalist officer, Dungan, "many were secretly saved by officers and soldiers." This happened despite Cromwell's order to kill everyone. Richard Talbot, who later became an important leader, was one of the few defenders to survive.

At least two Royalist officers who were initially spared were later killed. Three days after the town was stormed, Sir Edmund Verney, an Englishman, was walking with Cromwell. An old friend called him aside. But instead of a friendly talk, he was stabbed with a sword. Two days later, Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Boyle, an Anglo-Irish Protestant, was eating. An English Parliamentarian soldier came in and whispered something to him. Boyle stood up to follow the soldier. His hostess asked where he was going. He replied, "Madam, to die." He was shot after leaving the room.

Civilian Deaths

It is not clear how many civilians died during the attack on Drogheda. Cromwell mentioned "many inhabitants" of Drogheda among the dead in his report to Parliament. Hugh Peters, a chaplain in Cromwell's army, said the total number of deaths was 3,552. About 2,800 of these were soldiers. This means between 700 and 800 civilians were killed. However, John Barratt wrote in 2009 that "there are no reliable reports from either side that many [civilians] were killed."

The only surviving civilian story of the siege comes from Dean Bernard. He was a Protestant priest and a Royalist. He said that about 30 of his church members were hiding in his house. Parliamentarian troops fired through the windows. One civilian was killed, and another was wounded. The soldiers then broke into the house, firing their weapons. But an officer who knew Bernard stopped them from killing those inside. He recognized them as Protestants. So, the fate of Irish Catholic civilians might have been worse.

The week after Drogheda was stormed, Royalist newspapers in England claimed that 2,000 of the 3,000 dead were civilians. This idea was also used in English Royalist and Irish Catholic accounts. Irish church records in the 1660s claimed that 4,000 civilians had died at Drogheda. They called the attack "unmatched cruelty and betrayal."

Why Cromwell Acted That Way

Cromwell defended his actions at Drogheda in a letter. He wrote to the Speaker of the House of Commons:

I believe this is God's fair judgment on these cruel people. They have shed so much innocent blood. And this will help prevent more bloodshed in the future. These are good reasons for such actions, which otherwise would cause sadness and regret.

Historians have looked at the first part of this statement, "the righteous judgement of God," in two ways. First, it could mean that the killing of the Drogheda soldiers was revenge. It was for the Irish killing of English and Scottish Protestants in 1641. In this view, "barbarous wretches" would mean Irish Catholics.

However, Cromwell knew that Drogheda had not been taken by Irish rebels in 1641. It also had not been taken by Irish Confederate forces in the years after. The soldiers defending Drogheda were both English and Irish. They were Catholics and Protestants. The first Irish Catholic troops came to Drogheda in 1649. They were part of the alliance between the Irish Confederates and English Royalists. Historian John Morrill has argued that English Royalist officers were treated most harshly. They were not spared, were killed after being captured, and their heads were displayed. From this view, Morrill believes that by "barbarous wretches," Cromwell meant the Royalists. Cromwell thought they had refused to accept "God's judgment" in the English Civil War. He felt they were needlessly continuing the civil wars.

The second part of Cromwell's statement was that the killings would "tend to prevent the effusion of blood for the future." This is understood to mean that such harshness would stop future resistance. It would prevent more deaths. Another of Cromwell's officers wrote that "such extreme strictness was meant to discourage others from fighting." Indeed, the nearby towns of Trim and Dundalk surrendered or fled when they heard what happened at Drogheda.

Some writers, like Tom Reilly, have said that Cromwell's orders were not unusually cruel for that time. The rules of war then stated that if a fortified town refused to surrender and was then captured by force, its defenders could lose their lives. However, others have argued that while Arthur Aston refused to surrender, "the sheer scale of the killing [at Drogheda] was simply unheard of."

According to John Morrill, the killings at Drogheda "had no direct comparison in 17th century British or Irish history." The only similar case in Cromwell's career was at Basing House. There, 100 out of 400 soldiers were killed after a successful attack. Morrill states, "So the Drogheda massacre stands out for its cruelty, for its mix of harshness and planning, for its mix of hot- and cold-bloodedness."

See also

- Wars of the Three Kingdoms

- Irish battles

- List of massacres in Ireland

- Siege of Jerusalem

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |