Siege of Kehl (1796–1797) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Kehl |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Rhine Campaign of 1796 during the War of the First Coalition | |||||||

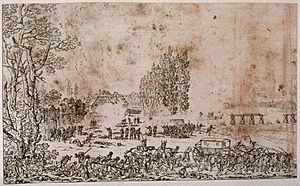

Habsburg and French troops skirmished for control of the crossing in the weeks before the siege. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 20,000 | 40,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 4,000 | 3,800 plus 1,000 captured | ||||||

The Siege of Kehl was a big battle that happened from October 26, 1796, to January 9, 1797. It was part of the French Revolutionary Wars, specifically the War of the First Coalition. In this battle, about 40,000 soldiers from Austria and Württemberg, led by Maximilian Anton Karl, Count Baillet de Latour, surrounded and captured the French-held forts at the village of Kehl.

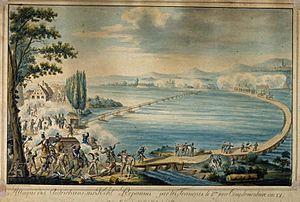

Kehl was a very important place. It had a bridgehead, which is like a fortified area protecting a bridge, that crossed the Rhine River into Strasbourg. Strasbourg was a key city for the French. This battle was a major part of the Rhine Campaign of 1796.

In the 1790s, the Rhine River was much wider and wilder than it is today. It had many channels and islands. The bridges and forts at Kehl and Strasbourg were built by a famous architect named Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban way back in the 1600s. These crossings had been fought over many times before. For the French, being able to cross the Rhine easily was super important for their army. The crossings at Kehl and Hüningen (near Basel) gave them access to southwestern Germany. From there, they could move their armies in many directions.

During the summer of 1796, French and Austrian armies moved back and forth across southern Germany. By October, the Austrian army, led by Archduke Charles, had pushed the French back to the Rhine. After a battle on October 24, the French army pulled back towards the river. The French commander, Jean Victor Marie Moreau, wanted a break in the fighting. Archduke Charles agreed because he wanted to send troops to Italy to help his army there. However, his brother, Emperor Francis II, and his military advisors said no. They made Charles attack Kehl and Hüningen at the same time. This kept his army busy at the Rhine all winter.

On September 18, 1796, the Austrians briefly took control of the bridgeheads at Kehl and Strasbourg. But a strong French counter-attack forced them to retreat. The situation stayed the same until late October. After the Battle of Schliengen, most of the French army went south to cross the Rhine at Hüningen. Meanwhile, Count Baillet Latour moved north to Kehl to start the siege. On November 22, the French defenders at Kehl, led by Louis Desaix, almost ended the siege. They launched a surprise attack and nearly captured the Austrian cannons. But in December, the Austrians made their siege stronger. They built a large semicircle of trenches and cannon positions around the village and bridges. By late December, the Austrian cannons could fire directly at the French defenses. The French defenders eventually gave up on January 9, 1797.

Contents

Understanding the Conflict

Why the War Started

In 1789, a big change called the French Revolution happened in France. At first, other European rulers thought it was just a problem between the French king and his people. But by 1791, the Holy Roman Emperor, Leopold, worried about his sister, Marie Antoinette, who was the Queen of France. In August 1791, Leopold and the King of Prussia warned France. They said that if anything happened to the French royal family, there would be serious consequences. French nobles who had left France also pushed for other countries to help stop the revolution.

On April 20, 1792, France declared war on Austria. This started the War of the First Coalition (1792–1798). France fought against most of the countries that shared borders with it. At first, France won some battles. But during a time called the Reign of Terror, many French generals were scared or even executed. This made the French army less effective.

At the end of the Rhine Campaign of 1795, the French and Austrian armies agreed to a truce. This truce lasted until May 20, 1796. Then, the Austrians announced it would end on May 31. The Austrian army had about 90,000 soldiers. Part of their army was on the east side of the Rhine, watching a French position. Other parts were guarding the Rhine from different points.

The original Austrian plan was to capture a city called Trier. Then they would attack the French armies one by one. But when news arrived about Napoleon Bonaparte's successes in Italy, 25,000 Austrian soldiers were sent to Italy. So, the Austrian leaders changed their plan. They gave Archduke Charles command of both Austrian armies and told him to hold his ground.

The Rhine River and Its Importance

The Rhine River flows west along the border between Germany and Switzerland. For about 80 miles, it cuts through steep hills. Further north, the land flattens out. The Rhine then turns north into a wide valley. This valley is bordered by the Black Forest on the east and the Vosges Mountains on the west. In 1796, this flat area, about 19 miles wide, had many villages and farms.

The Rhine River looked very different in the 1790s. It was wild and unpredictable. In some places, it was four times wider than it is today. Its channels wound through marshes and meadows. It created islands of trees and plants that were sometimes underwater during floods. The river could be crossed reliably at Kehl (near Strasbourg) and at Hüningen (near Basel). These places had systems of bridges and causeways.

Political Landscape of the Area

The German-speaking states on the east side of the Rhine were part of the Holy Roman Empire. This empire was a huge collection of over 1,000 different territories. These territories varied greatly in size and power. Some were tiny "little states" that were only a few square miles. Others were large and powerful. They were governed in different ways. Some were free cities, some were church-controlled lands, and others were ruled by powerful families.

On a map, the Empire looked like a "patchwork carpet" because of all the different pieces. Some states even had parts that were not connected to their main territory. The Holy Roman Empire had ways to solve problems between people and between different areas. Groups of states also worked together for economic reasons and for military protection.

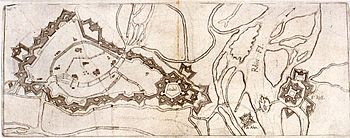

The forts at Hüningen and Kehl were very important bridgeheads across the Rhine. At Strasbourg and Kehl, the first permanent bridge was built in 1338. In 1678, France took over Strasbourg. The bridge became part of the city's defenses. The French King Louis XIV ordered the famous architect Vauban to build strong, star-shaped forts and bridgeheads in both locations. The main forts were on the French side of the Rhine. The bridgeheads and smaller forts protected the bridges and other crossings.

The 1796 Campaign

The 1796 campaign was part of the bigger French Revolutionary Wars. In these wars, France fought against a changing group of countries. These included Prussia, Austria, other German states, Britain, and others. At first, France won some battles. But from 1793 to 1795, they had less success. However, the countries fighting France had trouble working together.

At the end of the Rhine Campaign of 1795, the Austrian and French armies agreed to a truce in Germany. This truce lasted until May 20, 1796. Then, the Austrians announced it would end on May 31. The Austrian army had 90,000 soldiers. Part of their army was on the east side of the Rhine. Other parts were guarding the Rhine from different points.

The French had a plan for a spring attack. Two French armies would push against the sides of the Austrian armies in Germany. A third French army would go towards Vienna through Italy. One French army would push south from Düsseldorf. This was meant to draw Austrian troops away. Meanwhile, another French army would gather on the east side of the Rhine near Mannheim.

The plan worked. The first French army pretended to attack Mannheim. Archduke Charles moved his troops to meet them. Then, the second French army quickly marched south and attacked the bridgehead at Kehl. This was guarded by 7,000 inexperienced German troops. They held the bridgehead for a few hours but then retreated. The French reinforced the bridgehead and poured into Germany. In the south, another French group crossed the river near Basel and moved along the Rhine. Archduke Charles worried about his supply lines and began to retreat to the east.

By July, the French had taken over most of the southern German states. They forced these states to make separate peace deals. The French took a lot of money and supplies from them. However, the French generals were jealous of each other. The two French armies could have joined up and crushed the Austrians, but they didn't. Instead, they both kept pushing east. In August, the Austrian armies finally joined together. This turned the tide against the French. The French army in the north was defeated in several battles. This allowed Archduke Charles to send more troops south.

Early Fighting at Kehl: September 1796

While Archduke Charles and Moreau were moving their main armies, an Austrian general named Franz Petrasch fought the French at Bruchsal. The French troops there were observing Austrian forts and defending the way into France. The French initially pushed the Austrians back. But the French commander realized his force was too small. So, he began to retreat. On September 5-6, the Austrians and French had many small fights. These fights hid the Austrian plan to get closer to Kehl and take the Rhine crossing. By September 15, some French troops arrived in Kehl. They tried to make the forts stronger, but it was hard because the villagers didn't help and the soldiers were tired.

The Kehl fort was commanded by Balthazar Alexis Henri Schauenburg. He only had a small number of soldiers, which was not enough to defend such an important place. General Moreau sent more troops to Kehl, but the Austrians tried to stop them.

Before dawn on September 18, three Austrian groups attacked Kehl. They quickly took over the town's defenses, the village itself, and the fort. Their soldiers even reached one side of the old bridge. But they stopped there, thinking it was the last bridge.

The French tried several times to take back the bridges. They were pushed back by the Austrians' large numbers and heavy cannon fire. Finally, at 7:00 PM, the French got lucky. An Austrian commander and 200 men were captured inside the fort. The next Austrian commander was badly wounded. The French general, Schauenburg, returned with more troops from Strasbourg. At 10:00 PM, the Austrians still held some positions. But new French troops arrived, and the Austrians were pushed back. By 11:00 PM, the French had taken back the fort, Strasbourg, Kehl village, and all their defenses.

What Happened Next

The Austrian failure to hold Kehl in September 1796 gave the French army some safety. If the Austrians had held the crossing, they could have attacked the French army as it retreated. This would have trapped the French army in Germany. But because the Austrians couldn't take the crossing, they had to stay outside Kehl.

After a battle called Schliengen, the French general Moreau only had one way to escape: the small Rhine crossing at Hüningen. He used this to move his army back to France. The big question was who would control these important crossings after the 1796 campaign. Archduke Charles wanted to take control of the Rhine forts. If the French agreed to a truce, he could send many of his troops to Italy to help his army there. The siege of Mantua in Italy was long and costly for both sides. The French government was willing to give up Mantua for the Rhine bridgeheads, which they thought were more important for defending France. But Napoleon Bonaparte, who was fighting in Italy, refused. He believed Mantua was key to conquering Italy.

Charles told his brother, the Emperor, about the French offer. But the Emperor and his military advisors completely refused it. They told Charles to besiege the forts, take them, and stop any French access to southern Germany. They still thought Austrian forces could save Mantua. By keeping Charles busy at the Rhine, besieging the strong forts at Kehl and Hüningen, they sealed the fate of the Austrian troops in Mantua. After it was clear Charles was stuck at the Rhine, Moreau sent many French troops to Italy. Mantua fell on February 2, 1797.

The Siege Begins

Once the Emperor refused Charles's plan, General Latour began the siege of Kehl. Another general, Karl Aloys zu Fürstenberg, was in charge of the siege at Hüningen. Laying siege in the 1700s was complex. Armies would surround a city and wait for those inside to give up. If waiting didn't work, they might try to bribe someone inside. An attacker might offer good terms to a defender who surrendered quickly. This saved time, money, and lives.

As a siege went on, the defenders' situation got worse. The attacking army would build earthworks, which are like dirt walls, to completely surround the target. This stopped food, water, and supplies from getting in. They would also build another line of earthworks to protect themselves from any outside armies.

Usually, time was on the side of the defenders. Most armies couldn't afford to wait too long. Before gunpowder weapons, defenders had a big advantage. But with large cannons and howitzers, traditional defenses became less effective. Still, many of the strong "star-shaped" forts were very challenging to attack.

Kehl's Fortifications

The main bridge over the Rhine started about 400 paces (steps) from where the Kinzig River joined the Rhine. The fort itself was between the Rhine bridge and the Kinzig. It was shaped like a polygon, about 400 feet long. Two sides faced the Rhine. The main wall was about 12 feet high. Below it were strong gun positions, called casemates, that were 83 feet long and 16 feet wide. These allowed cannons to fire along the length of the enemy's lines. Behind these were two other fortified areas that held supplies. All the walls were thick enough to stop most cannon fire. Inside, there were barracks for up to 1500 men. These buildings had already survived heavy Austrian bombing in September 1796.

The fort also had stone and mortar outworks, called ravelins, and each main defense had its own hornwork (a V-shaped defense). The hornwork between the Rhine and the Kinzig was about 250 feet long. These hornworks also had stone walls, a covered ditch for communication, and a sloping earth bank.

The village of Kehl was built on one of these hornworks, along a single long street. At one end was the Commandant's Bridge, which crossed a smaller channel of the Rhine, about 400 feet wide. Near this channel were the Kehl church and graveyard. The fortified wall by the churchyard had its own moat. This wall had room for at least four cannons and 150-200 soldiers. This whole area, called the churchyard redoubt, was about 100 yards wide and controlled the area.

As the Rhine passed the church, it curved sharply. This curve and where the water channels rejoined created a small island called Marlener Island. In dry weather, it was more like a peninsula. Next to this was a larger island, Erlenkopf, which had cannons. This cannon position was protected by wooden posts and connected to the mainland by a light wooden bridge. The river near the bridge was about 200 yards wide.

In the other direction, between Kehl and another stream, the fortifications were also strong. A redoubt there held about 8 cannons and 400 men. It covered the road between a small village and Kehl.

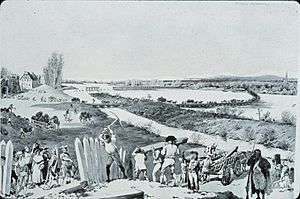

How the Siege Happened

The French knew the siege was coming. So, on October 26, they destroyed most of Kehl village. Only the ruined walls of the church and post office remained. The French kept control of three main islands around the Kehl crossings. These islands were important for their operations. They were connected to Kehl and to each other by temporary bridges. Troops could also move by boat.

On October 26, General Latour immediately started building long earthworks around the bridgehead. These trenches, closest to the French, had a series of small forts connected by ditches. At first, the French thought these were just for defense and ignored the Austrians. They focused on strengthening their own defenses, which were not very strong. After several days, by October 30, they brought up more cannons. Also, General Dessaix arrived to command the fort and brought more troops. The French then worked harder to rebuild the fort and its defenses. They also made several small attacks against the Austrian lines. On November 14, a French group attacked the most forward Austrian positions and took 80 Austrian prisoners. On November 21, the French planned a bigger attack.

The Attack of November 22

At dawn on November 22, 16,000 French foot soldiers and 3,000-4,000 cavalry attacked the Austrian and Württemberg positions. The French infantry came from a small island and from their camp. The first group forced their way into two Austrian forts. Another group broke through the earthworks in the center and took a village and two forts next to it. But three other forts were not taken. The Austrians then rushed out of these forts and attacked the French. This big attack surprised the Austrians. General Latour and Archduke Charles personally went to the gap the French had made. They brought six battalions of armed workers and all the Austrian troops with them.

The French immediately ran into problems. The infantry meant to help the first wave didn't arrive in time. The cavalry couldn't move properly because the ground was marshy and the space was tight. After four hours, the entire French attacking group pulled back. They took 700 prisoners, seven cannons, and two howitzers. They couldn't take another 15 cannons because they didn't have enough horses, so they made them unusable. The French said that thick fog helped the Austrians because it stopped the French from seeing what was happening. The fighting was very heavy. General Moreau himself was wounded in the head. General Desaix's horse was killed, and he hurt his leg. General Latour's horse was also shot. This battle convinced the French that the Austrian forces were too many and too strong to defeat. So, the French focused on making their own defenses stronger.

Expanding the Siege

Much of the Kehl fort was built on old ruins. One of the oldest bridges had been mostly destroyed earlier. The French were rebuilding it. Where old wooden stakes remained, they rebuilt the bridge. Where stakes were missing, they used temporary pontoon bridges. By November 28, the Austrians had built enough trenches and cannon positions to fire on this old bridge. The bridge was completely destroyed. The French repaired it, and the Austrians destroyed it again. It was an easy target. The French couldn't keep it intact for three days in a row. Its wreckage also threatened a pontoon bridge nearby.

The Austrians kept expanding their works and building new cannon positions. On December 6, the Austrians fired all their cannons at once, all day long. At 4:00 PM, they attacked a French position defended by 300 men. They took it, but the French counter-attacked and got it back, taking some prisoners. At the same time, the Austrians attacked another position called the Bonnet de Prétre, where only 20 men were stationed. They took it and connected it to their network of forts. This gave Austrian sharpshooters close access to the bridges. They could shoot French defenders with muskets. It also allowed engineers to dig tunnels under the bridgehead walls and set up cannons closer to the walls. They built new trenches near the old village of Kehl.

The French also made several night attacks on the Austrian works. They would chase the diggers out of the trenches. But the Austrian reserves always got the positions back before the French could capture any cannons or destroy the construction. So, every day, the Austrians expanded their works and built new cannon positions.

On December 9, at night, the Austrians attacked the French positions at the ruins of the old post office and church in Kehl. The fighting was short but fierce. The Austrians finally took the position, but they were driven out the next morning. In this attack, where Archduke Charles was present, the Austrians lost about 300 men and an officer. They attacked again on December 10 and 11 but couldn't take the positions. The Austrians also sent fire ships to destroy the pontoon bridge, but these were stopped. The Austrians did take Ehrlinrhin, a large island where some French reserve units were. A French general, Lecourbe, removed one of the temporary bridges to cut off any hope of French retreat. He grabbed a flag and rallied a group of soldiers to attack the Austrians. He pushed them back to their trenches. Lecourbe's quick thinking saved half of the island for the French.

In the following days, the Austrians added the newly captured land to their large lines and cannon positions. They opened trenches near the old village of Kehl. Within a week, the Austrian cannon positions connected the ruins at Kehl with their left flank. They also linked the entire line to one of the Rhine islands, which was now exposed by low water. The Austrian lines, made of several small forts, were joined by trenches that completely surrounded Kehl and the access to the bridges. These lines started near a village, crossed roads, rivers, surrounded another village, and ended at the Bonnet de Prétre. The Austrian troops on the island could protect the left side. The entire attacking army was protected by strong trenches on the islands in the Kinzig. By the end of the week, the Austrian defenses were connected in a large semicircle around the village. The Austrians took the ruins of the church and the post office by bringing up cannons and bombing the positions. This allowed them to complete their lines.

According to spies and deserters, Archduke Charles himself was encouraging his troops. Moreau reported that he "prepared his troops by speeches and gifts." On January 1, after a long cannon attack, 12 Austrian groups attacked the outer fort and the right side of the French defenses. They drove the French out and immediately took the earthworks and six cannons. French reserves couldn't cross the Rhine fast enough. Boats meant to carry troops had been damaged by the long cannon fire. The connecting bridges, also damaged, were repaired quickly. But by the time these repairs were made, the Austrians were strongly dug into their new positions. The French couldn't force them out. Even miners, who had dug under the trenches, couldn't blow up the fort.

The Surrender

Day by day, the Austrians put more pressure on the French. The French had trouble bringing in enough reserve troops because of damaged bridges and transport. Boats were hit by cannon fire. By the time bridges were repaired and enough reserves could move, the Austrians were dug in and had brought up their cannons. The Austrians kept advancing their earthworks and improving their cannon positions.

At 10:00 AM on January 9, the French general Desaix suggested giving up to General Latour. They agreed that the Austrians would enter Kehl the next day, January 10, at 4:00 PM. The French immediately repaired the bridge, making it usable by 2:00 PM. This gave them more than 24 hours to take everything valuable and destroy everything else. By the time Latour took control of the fort, nothing useful remained. All the wooden defenses, ammunition, and even the carriages for bombs and howitzers had been taken away. The French made sure nothing was left for the Austrian army. The fort itself was just earth and ruins. The siege ended 115 days after it began. Active fighting had lasted for 50 days.

What Happened After

The Austrians lost about 12% of their soldiers in the siege. This was a high number for a siege in the 1700s. These losses were due to the French surprise attacks that caused heavy damage. One estimate says that out of 40,000 Austrian soldiers, 4,800 were lost. Another estimate says Austrian losses were lower: 3,000 killed or wounded and 1,000 captured.

The surrender at Kehl on January 9 allowed Archduke Charles to send more troops and heavy cannons to Hüningen. On February 2, 1797, as the Austrians prepared to attack the Hüningen bridgehead, the French commander offered to surrender. On February 5, the Austrians finally took control of Hüningen. The Holy Roman Emperor then honored the general who led the siege at Hüningen.

Armies in the Battle

French Army

The French fort had its headquarters and three mixed divisions.

- Commanders: General Louis Desaix (later replaced by Laurent Gouvion Saint-Cyr)

- General Jean Baptiste Eblé (Artillery Commander)

- General Anne Marie François Boisgérard (Engineers Commander)

- François Louis Dedon-Duclos (Bridges)

- 1st Division: General Jean-Jacques Ambert

- Brigade: General Louis-Nicolas Davout (3rd, 10th, 31st Demi-brigades)

- Brigade: General Charles Mathieu Isidore Decaen (44th, 62nd Demi-brigades)

- 2nd Division: General Guillaume Philibert Duhesme

- Brigade: General Jean Marie Rodolph Eickemayer (68th, 76th Demi-brigades)

- Brigade: General Claude Lecourbe (84th, 93rd Demi-brigades)

- 3rd Division: General Gilles Joseph Martin Bruneteau (called Saint-Suzanne)

- Brigade: General Joseph Hélie Désiré Perruquet de Montrichard (97th, 100th Demi-brigades)

- Brigade: General Jean Victor Tharreau (103rd, 106th, 109th Demi-brigades)

In total, there were 40 battalions. Moreau said that 15 battalions were on duty every day. Six battalions defended the Kehl fort itself. Three held the trenches. Three occupied the Ehrlen islands, and three held the Kinzig island. Six battalions were kept as a reserve on the other side of the Rhine. He also rotated battalions through the trenches so they wouldn't get too tired. He also had more troops available from the main French army.

Austrian Army

The Austrian force included foot soldiers, three columns, and cavalry.

- Commander: General Maximilian Anton Karl, Count Baillet de Latour (also Artillery Commander)

- Artillery Commander: Lieutenant Field Marshal Johann Kollowrat

- Engineers Director: Colonel Szeredai

Infantry

1st Column

2nd Column

|

3rd Column

Cavalry

|

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |