Rhine campaign of 1796 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rhine campaign of 1796 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the First Coalition | |||||||

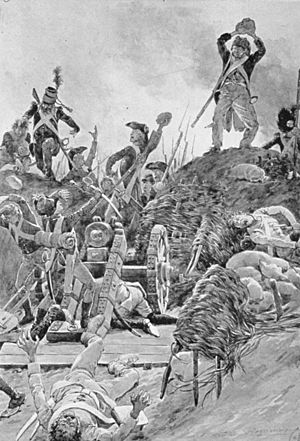

Taking one of the redoubts of Kehl by throwing rocks, 24 June 1796, Frédéric Regamey |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Lower Rhine Army of the Upper Rhine |

Army of Sambre and Meuse Army of the Rhine and Moselle |

||||||

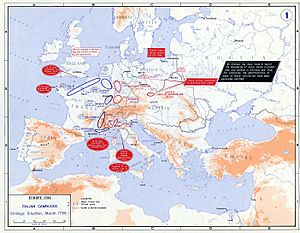

The Rhine campaign of 1796 was a major part of the French Revolutionary Wars. It happened between June 1796 and February 1797. In this campaign, two armies from Austria and its allies fought against two French armies. The Austrian forces, led by Archduke Charles, managed to outsmart and defeat the French. This was the last big campaign of the War of the First Coalition.

The French had a big plan to invade Austria. They wanted to surround the capital city, Vienna, and force the Holy Roman Emperor to give up. They sent three armies. Two armies, led by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan and Jean Victor Marie Moreau, were sent to Germany. A third army, led by Napoleon Bonaparte, went through Italy.

At first, Napoleon's army did very well in Italy. This made Archduke Charles send 25,000 of his soldiers to Italy to help. This weakened the Austrian forces along the Rhine River. Later, Jourdan's army made a fake attack in the north. This tricked Charles into moving more troops there. This allowed Moreau's army to cross the Rhine River at the Battle of Kehl on June 24.

By late July, both French armies had pushed deep into Germany. They forced many smaller German states to sign peace agreements. But the French armies spread themselves too thin. Also, the French generals didn't work well together. Charles used this to his advantage. He left a smaller army to face Moreau in the south. Then, he moved many of his best soldiers to the north to fight Jourdan.

Charles defeated Jourdan's northern army at the Battle of Amberg on August 24 and the Battle of Würzburg on September 3. Jourdan's army had to retreat all the way back to the west side of the Rhine. With Jourdan's army out of the way, Charles focused on Moreau. He forced Moreau to retreat south. During the winter, the Austrians took back the French bridgeheads (areas on the east side of the river) at Kehl and Hüningen. Moreau's army also had to go back to France. Even though Charles won in Germany, Austria lost the overall war in Italy to Napoleon. This led to a peace treaty called the Peace of Campo Formio.

Contents

Why This War Happened

The French Revolution started in 1789. At first, other European rulers thought it was just a problem inside France. But as the French revolutionaries became more extreme, other kings and queens got worried. They felt that what happened to the French royal family could happen to them. In 1791, several European rulers, including Austria, threatened France if anything happened to the French king, Louis XVI.

French people who had left France (called émigrés) also wanted to bring back the old system. They had support from Austria, Prussia, and Britain. Finally, on April 20, 1792, France declared war on Austria. This pulled most of the Holy Roman Empire into the war. This was the start of the War of the First Coalition (1792–1798). France fought against many European countries that shared borders with it, plus Great Britain.

From 1793 to 1795, France had mixed success. By 1794, the French army was changing a lot. The most extreme revolutionaries removed officers who might still be loyal to the old king. They also started a "mass draft" (called levée en masse). This brought thousands of new, untrained men into the army. Many officers were chosen for their loyalty to the Revolution, not for their military skills. The French army also had problems with supplies and discipline. Soldiers often had to take food and supplies from the countryside. After April 1796, soldiers were paid in metal money instead of worthless paper money, but they were still paid late. The French government believed that war should pay for itself. So, they needed to invade new lands to get money and supplies.

The Many States of the Holy Roman Empire

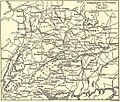

The lands on the east side of the Rhine River were mostly German-speaking. They were part of a huge group of territories called the Holy Roman Empire. Austria was a very important part of this Empire, and its ruler was usually the Holy Roman Emperor. The French government saw the Holy Roman Empire as its main enemy in Europe.

In 1796, the Empire had over 1,000 different areas. These included places like Breisgau (controlled by Austria), free cities like Offenburg, and lands belonging to noble families. Many of these areas were not connected. A village might belong to one ruler, but a single farm or even a few fields might belong to another. The size and power of these areas varied greatly. Some were tiny, just a few square miles. Others were large, like Bavaria and Prussia.

These states were governed in different ways. Some were independent cities, some were church lands, and some were ruled by families. Groups of states formed "Imperial Circles" to work together. They shared resources and protected their interests, like trade and defense. Without help from big states like Austria or Prussia, these small states were easy targets for invasion.

The Rhine River: A Natural Border

The Rhine River was a natural border between the German states of the Holy Roman Empire and France. To attack, either side needed to control the river crossings. The river starts in Switzerland and flows north. The part between Switzerland and Basel, called the High Rhine, flows through steep hills.

At Basel, the land flattens, and the Rhine turns north into a wide valley. This valley is about 31 kilometers (19 miles) wide. It's bordered by the Black Forest mountains on the German side and the Vosges mountains on the French side. Further north, the river becomes deeper and faster. It then widens into a delta before flowing into the North Sea.

In the 1790s, the river was wild and unpredictable. Armies had to be very careful when crossing. River channels twisted through marshes and meadows. Flash floods from the mountains could cover farms. Armies could only cross reliably at specific points. In 1790, there were good bridges at Kehl (near Strasbourg), Hüningen (near Basel), and Mannheim in the north. Sometimes, crossings could happen at Neuf-Brisach, but it was risky. Only north of Kaiserslautern did the river have clear banks with strong, fortified bridges.

War Plans

The fighting along the Rhine had stopped in 1795, but both sides were planning for more war. On January 6, 1796, Lazare Carnot, one of France's leaders, decided that Germany was more important than Italy for the war. France's money situation was bad. So, their armies were expected to invade new lands and live off what they found there. Knowing France planned to invade, Austria announced on May 20, 1796, that the truce would end on May 31.

Austria's Plan

Austria and its allies had about 125,000 soldiers. About 90,000 of these were led by the 25-year-old Archduke Charles. He was the brother of the Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II. Before the campaign started, Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser took 25,000 of these soldiers to Italy. This was because Napoleon was doing well there.

The Austrian plan was to capture the city of Trier. From there, they would attack each French army one by one. If that didn't work, Charles was told to hold his ground.

A group of 20,000 Austrian soldiers was in the north, watching the French at Düsseldorf. Another 10,000 soldiers guarded the fortresses of Mainz and Ehrenbreitstein. Charles put most of his main force, led by Count Baillet Latour, between Karlsruhe and Darmstadt. This area was important because the Rhine and Main rivers met there, making it a likely place for an attack.

The far left side of the Austrian army, led by Anton Sztáray and others, guarded the Rhine from Mannheim to Switzerland. This part of the army included soldiers from the Imperial Circles (local militias). Charles didn't like using these militias in important places. So, when it seemed the French would cross the middle Rhine, he put the militias at Kehl. These were mostly untrained farmers and day laborers. The rest of the force included experienced Austrian soldiers and some French royalists.

Compared to the French, Charles had half the number of troops. They were spread out along a 340-kilometer (210-mile) front from Switzerland to the North Sea. The Imperial troops couldn't cover this huge area well enough to stop the French.

France's Plan

Lazare Carnot's big plan was for the two French armies along the Rhine to attack the Austrian sides. These armies were led by two very experienced generals: Jean-Baptiste Jourdan and Jean Victor Marie Moreau. Jourdan commanded the Army of Sambre and Meuse, and Moreau commanded the Army of the Rhine and Moselle.

Moreau's army was positioned east of the Rhine at Hüningen and north near Landau. Jourdan's army, with 80,000 men, was already on the west side of the Rhine. In the north, Jean Baptiste Kléber had 22,000 troops in a fortified camp at Düsseldorf. Kléber was supposed to push south from Düsseldorf. Jourdan's main force would then attack Mainz and cross the Rhine into Franconia. The French hoped this would make the Austrians pull all their forces from the west side of the Rhine.

While Jourdan drew Austrian attention north, Moreau was to cross the Rhine at Neuf-Breisach, Kehl, and Hüningen. He would invade Baden, attack Mannheim, and conquer Swabia and Bavaria. Eventually, Moreau was supposed to march towards Vienna. Jourdan, after taking most of Franconia, would turn south to protect Moreau's back as he advanced.

At the same time, Napoleon Bonaparte was to invade Italy. He would defeat the Kingdom of Sardinia and take Lombardy from the Austrians. The Army of Italy was told to cross the Alps and join the other French armies in Germany. By spring 1796, Jourdan and Moreau each had 70,000 men. Bonaparte's army had 63,000.

The Battles Begin!

Crossing the Rhine River

As planned, Kléber made the first move. He advanced south from Düsseldorf against the Austrian forces. On June 1, 1796, Kléber's troops captured a bridge over the Sieg River. A second French division also threatened the Austrian left side. The Austrian commander retreated south. On June 4, Kléber defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Altenkirchen. The French captured 1,500 Austrian soldiers and 12 cannons.

After this loss, Charles replaced the Austrian commander with Wilhelm von Wartensleben. Jourdan's main army crossed the Rhine on June 10 at Neuwied to join Kléber. The French Army of Sambre and Meuse then moved towards the Lahn River.

Charles left 12,000 troops to guard Mannheim. He quickly moved his other soldiers north against Jourdan. Charles defeated Jourdan's army at the Battle of Wetzlar on June 15, 1796. Jourdan quickly retreated back to the west side of the Rhine. The Austrians then attacked Kléber's forces, causing 3,000 French casualties. After his success, Charles left 35,000 men with Wartensleben and 30,000 in fortresses. He then moved south with 20,000 troops to help Latour.

While Charles was fighting in the north, Moreau's army was busy in the south. On June 15, Moreau's troops defeated 11,000 Austrians at Maudach. The French lost 600 soldiers, while the Austrians lost three times as many. Moreau then marched his army south to Strasbourg. His advance guard crossed the Rhine at Kehl on the night of June 23/24.

The Austrian position at Kehl was not well defended. On June 24, the French attacked the Swabian (German militia) soldiers on the bridge. The French had 10,065 soldiers in the first attack and lost only 150. The Swabians were greatly outnumbered and couldn't get help. Most of the main Austrian army was still near Mannheim, where Charles expected the main attack. The Swabians lost 700 soldiers and 14 cannons. Moreau sent more troops to Kehl, so he had 30,000 soldiers there.

On the same day, another French force crossed the Rhine near Basel. This gave the French a "pincer" effect. Jourdan's army was coming from the north, Moreau's main army from the center, and this third force from the south.

Within a day, Moreau had four divisions across the river. This was a big success for the French plan. From the south, the French chased the Austrians east. Latour and Sztáray tried to hold a line along the Murg River. On July 5, 1796, the French defeated Latour at the Battle of Rastatt. They pushed his forces back to the Alb River. The Austrian armies didn't have enough soldiers to stop Moreau. They needed help from Charles, who was still busy fighting Jourdan in the north.

France Pushes Forward

Charles realized he needed more soldiers. He feared Moreau's surprise crossings at Kehl and Hüningen. So, he arrived near Rastatt with more troops and prepared to attack Moreau on July 10. But the French attacked first on July 9. In the Battle of Ettlingen, Charles fought off the French attacks on his right side. But the French gained ground on the hills to the east and threatened his side. Charles lost 2,600 soldiers, and Moreau lost 2,400. Worried about his supply lines, Charles began a careful retreat to the east.

French successes continued. With Charles gone from the north, Jourdan crossed the Rhine again. He pushed Wartensleben's army back behind the Lahn River. The French Army of Sambre and Meuse then defeated the Austrians at Friedberg (Hessen) on July 10. Jourdan captured Frankfurt am Main on July 16. He left 28,000 troops to block Mainz and Ehrenbreitstein. Then, Jourdan continued up the Main River. He kept attacking Wartensleben's northern side, forcing the Austrian general to retreat further. Jourdan's army had 46,197 men, while Wartensleben had 36,284. Wartensleben felt it was too risky to attack the larger French force. He kept retreating northeast, moving further away from Charles's army. The French were encouraged by their advance and by capturing Austrian supplies. They captured Würzburg on August 4. Three days later, Jourdan's army won another battle at Forchheim on August 7.

Meanwhile, in the south, Moreau's army kept fighting Charles's retreating army. This happened at Cannstatt near Stuttgart on July 21, 1796. The local German states started talking to Moreau about peace. By mid-July, Moreau's army controlled most of southwestern Germany. Many states signed peace agreements. The Imperial troops (local militias) mostly left the campaign. Their commander disarmed them on July 29, and they went home. Charles retreated with his Austrian troops through Geislingen an der Steige around August 2. He was in Nördlingen by August 10. At this time, Moreau had 45,000 men spread out over a 40-kilometer (25-mile) front. Charles planned to cross the Danube River, but Moreau was too close. So, Charles decided to attack instead.

Austria Fights Back

The Battle of Neresheim on August 11 was a turning point. It was a series of fights where the Austrians pushed back Moreau's right side. They almost captured his artillery. When Moreau prepared to fight the next day, he found that the Austrians had left and were crossing the Danube. Both armies lost about 3,000 men.

Jourdan also faced problems in the north. On August 17, the Austrians caused 1,000 French casualties at Sulzbach. Despite their losses, the French kept advancing. Wartensleben's army retreated behind the Naab River on August 18. Jourdan sent a division to watch Charles, hoping to prevent a surprise attack. But Charles was getting more soldiers south of the Danube. His army grew to 60,000 troops. He left 35,000 soldiers to hold Moreau's army along the Danube.

By now, Charles clearly understood that if he could join forces with Wartensleben, he could defeat both French armies one after the other. He had enough new soldiers. He also changed his supply route to Bohemia. He planned to move north to meet Wartensleben. If Wartensleben wouldn't come to him, Charles would go to Wartensleben. With 25,000 of his best troops, Charles crossed to the north side of the Danube at Regensburg.

On August 22, 1796, Charles met a French division at Neumarkt. The French were outnumbered and pushed back. Charles then attacked Jourdan's right side. Jourdan's army fell back to Amberg as Charles and Wartensleben's forces came together. On August 20, Moreau had sent Jourdan a message saying he would follow Charles closely, but he didn't. In the Battle of Amberg on August 24, Charles defeated the French. The Austrians lost only 400 soldiers. The French lost 1,200 killed and wounded, plus 800 captured. Jourdan retreated. He now faced an enemy that was stronger than his own army.

As Jourdan retreated, he saw a chance to save his campaign by fighting at Würzburg, an important stronghold. But at this point, problems between the French generals became serious. Jourdan had a fight with his commander, Kléber, who suddenly resigned. Two other generals also left the army. Jourdan had to reorganize his troops. He marched south with 30,000 men.

Charles rushed his army towards Würzburg. On September 3, the Austrians won the Battle of Würzburg. They forced the French to retreat to the Lahn River. Charles lost 1,500 soldiers, while the French lost 2,000 killed and wounded, plus 1,000 captured. The losses at Würzburg forced the French to stop their attack on Mainz on September 7. They moved those troops to help their lines further east.

On September 10, more French troops joined Jourdan's army. These 12,000 soldiers had been blocking the east side of Mainz. This brought Jourdan's army to 50,000 men. But the French abandoning the attacks on Mainz, and later Mannheim and Philippsburg, freed up many Austrian soldiers to join Charles.

Moreau seemed unaware of Jourdan's problems. He was still far to the east of Jourdan. Moreau crossed to the south side of the Danube on August 19. By August 20, Moreau knew Charles had crossed the Danube and was heading north. But instead of chasing Charles, Moreau pushed east. On August 24, the Austrians fought Moreau near Augsburg. The French attacked across the river. In the Battle of Friedberg (Bavaria), the French crushed an Austrian regiment. They caused 600 killed and wounded, and captured 1,200 men and 17 cannons. French casualties were 400. This was the last big French victory of the campaign.

French Retreat

It soon became clear that Moreau's army, like Jourdan's, was alone and too spread out. It had to retreat. In September, Austrian forces chased Moreau's army. On September 18, the Austrians briefly captured the fortified bridgehead at Kehl. But a French counterattack drove them out. Both sides lost 2,000 soldiers.

Moreau began retreating on September 19. By September 21, his army reached the Iller River. On October 1, the Austrians attacked but were pushed back. On October 2, Moreau's army, with 39,000 troops, defeated Latour's 24,000 men in the Battle of Biberach. The French lost 500 soldiers, while the Austrians lost 300 killed and wounded, and 4,000 captured. After this, Latour followed the French more carefully.

Moreau wanted to retreat through the Black Forest. But the Austrians blocked that path. Instead, his army went through a different valley and reached Freiburg im Breisgau on October 12. Moreau wanted to reach Kehl further down the Rhine. But by this time, Charles was blocking the way with 35,000 soldiers. To allow his supply trains to escape, Moreau needed to hold his position for a few days. The Battle of Emmendingen was fought on October 19. The French lost 1,000 killed and wounded, plus 1,800 captured. The Austrians lost 1,000 soldiers.

Moreau sent part of his army to the west side of the Rhine at Breisach. With the main part of his army, he offered battle at Schliengen. In the Battle of Schliengen on October 24, the French lost 1,200 soldiers. The Austrians lost 800. The French held off the Austrian attacks but retreated the next day. They crossed back to the west side of the Rhine on October 26. In the south, the French held two bridgeheads on the east bank. Moreau ordered his generals to defend Kehl and Hüningen.

Armistice Refused and Subsequent Sieges

Moreau offered Charles a truce. Charles wanted to accept it so he could send 10,000 more soldiers to Italy. But the Austrian war advisors told him to refuse. They ordered him to capture Kehl and Hüningen. While Charles was told to take these cities, in early January, the French began sending two divisions to Napoleon's army in Italy.

Instead of sending similar numbers of men to Italy, Charles gave Latour 29,000 infantry and 5,900 cavalry. He ordered him to capture Kehl. The Siege of Kehl lasted from November 10 to January 9, 1797. The French lost 4,000 soldiers, and the Austrians lost 4,800. The French agreed to surrender Kehl in exchange for being able to leave the city without being attacked. Similarly, the French gave up the bridgehead at Hüningen on February 5.

What Happened Next?

Moreau's ability to send troops to Italy, and Charles's inability to do so, made a big difference in the Italian campaign of 1796. At the start of the campaign, French planners thought the best way to Vienna was through Germany, not Italy. So, they put most of their forces on the Rhine. The army that controlled the opposite bank controlled access to the crossings. Because of this, the Italian campaign only had 37,000 men and 60 cannons. They faced over 50,000 Allied troops. But Napoleon still managed to separate the Sardinians from their Austrian allies. He also separated the Neapolitans from the Austrians.

While defending the besieged bridgeheads at Kehl and Hüningen, Moreau had been moving troops south to help Napoleon. The Austrian defeat in the Battle of Rivoli in January 1797 allowed Napoleon to surround and capture an Austrian relief force. Soon after, the city of Mantua surrendered to the French. Napoleon's forces continued to advance towards Austria. After a short campaign where Archduke Charles commanded the Austrian army, the French reached Judenburg, about 161 kilometers (100 miles) from Vienna. The Austrians agreed to a five-day truce. Napoleon claimed to have captured 150,000 prisoners, 170 flags, and many cannons. This campaign was a huge victory for Napoleon. In the Rhineland, Charles returned things to how they were before the war.

On April 18, 1797, Austria and France agreed to a truce. This led to five months of talks, which resulted in the Peace of Campo Formio on October 18, 1797. This treaty ended the War of the First Coalition. The peace lasted until 1798 when both sides rebuilt their armies and started the War of the Second Coalition.

Images for kids

Sources

- Barton, Sir Dunbar. Bernadotte: The First Phase. London: John Murray, 1914.

- Bertrand, Jean Paul, R.R. Palmer (trans). From Citizen-Soldiers to Instrument of Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- Graham, Thomas, 1st Baron Lynedoch, (sometimes attributed to). The History of the Campaign of 1796 in Germany and Italy, London, (np), 1797.

- Rothenberg, Gunther E. (Feb 1973), "The Habsburg Army in the Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815)". Military Affairs, 37:1, pp. 1–5.

Web

- Rickard, J. Battle of Ettlingen, 9 July 1796, History of War, 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- Rickard, J. Combat of Siegburg, 1 June 1796, History of War, 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Rickard, J. First Battle of Altenkirchen, 4 June 1796, History of War, 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Smith, Digby and Leopold Kudrna. Austrian Generals of 1792–1815: Württemberg, Ferdinand Friedrich August Herzog von, Napoleon Series. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |