Sir John Smythe (soldier) facts for kids

Sir John Smythe (c. 1531 – August 1607) was an English soldier, diplomat, and writer about military topics. He was known for his strong opinions and his detailed writings on warfare.

Contents

Early Life and Education (1531–1572)

John Smythe was born in Essex, England, around 1531. He was the oldest son of Sir Clement Smith, who was a Catholic official. His mother was Dorothy Seymour. John's family had some connection to the royal family through his mother's side. Queen Elizabeth I even called him "a gentleman of her family."

Smythe went to Oxford, but he did not finish his degree. However, he learned a lot there. He often quoted famous Greek and Roman writers in his later works. This shows he had a good education. Even as a teenager, he gained military experience. He fought in two rebellions in England in 1549: Kett's Rebellion and the Western Rising.

Military Career in Europe (1552–1576)

In 1552, Smythe's father passed away, and John inherited his family's property. He sold some of it to fund his travels and military training in Europe. He volunteered to fight in France, the Low Countries, and Hungary. In Hungary, he fought against the Turks in 1566. This caught the attention of Maximilian II, the Holy Roman Emperor. Smythe also joined other English volunteers to fight with Philip II of Spain in the Mediterranean.

Smythe returned to England in 1572. His time fighting in Europe made him a very skilled soldier and gentleman. He learned many different military techniques and practices. These experiences shaped his strong beliefs, which he later wrote about in his books. During his time abroad, Smythe also changed his religious views. He moved away from his father's Catholicism and likely became a Protestant.

Ambassador to Spain (1576–1577)

On November 18, 1576, Queen Elizabeth I chose Smythe to be her special ambassador to Spain. He was a good choice because he knew Spanish customs and military tactics. He also spoke Spanish fluently and was well-liked by the Spanish court. His cousin, Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford, also helped him get the job. Because of this important role, he was knighted in 1576. He also visited King Henry III of France on his way to Spain. He was paid a good salary for his work.

Smythe became ambassador at a difficult time for England and Spain. England was supporting the Dutch Revolt against Spain. Smythe's job was to help keep peace between the two countries. Queen Elizabeth wanted to avoid war with Spain for as long as possible. Smythe also had to protect English merchants in Spain. He also tried to help English Protestants who were being held by the Spanish Inquisition.

Smythe met with King Philip II of Spain on January 24, 1577. He worked hard to keep peace between England and Spain. He convinced Philip to maintain peace with Queen Elizabeth. However, he struggled to protect English people from the Inquisition. He had many disagreements with the General Inquisitor, Gaspar de Quiroga. Their meetings often became heated. Smythe even forced his way into Quiroga's house once, leading to a very tense argument.

Despite these difficulties, Smythe did help some English prisoners get released. He was recalled to England on July 28, 1577.

Life Back in England (1577–1585)

After returning to England, Smythe lived a quiet life as a country gentleman. He had less money than before. He was sometimes fined for not taking care of his property. This period was mostly uneventful for him.

Political Comeback (1585–1588)

In 1585, the Anglo-Spanish War began. This led to disagreements within the English court. One group, led by Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, wanted to fight Spain directly. Another group, led by William Cecil, Lord Burghley, wanted to try diplomacy and avoid expensive wars.

Smythe was chosen to be an ambassador to a Spanish military leader, Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma. This put him in the group that wanted peace. However, this mission was soon canceled.

Smythe then became a strong critic of those who he felt were wasting English soldiers' lives in foreign wars. He also spoke out against the practice of impressment, which forced people into the navy. This opinion was not popular with the court. In 1587, Smythe was asked to train 2,000 English soldiers in Essex. His own reports said he did a good job. But the next year, Dudley, who favored war, had him removed from this position. Dudley claimed Smythe's training was a failure. Smythe's standing in politics became much weaker after this.

Military Writer (1590–1595)

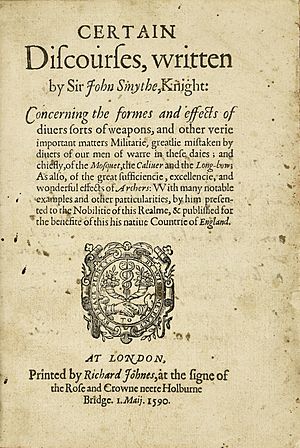

After losing his political influence, Smythe started writing about military topics. In May 1590, he published a book called Certain Discourses. This book was about military strategy.

The Queen's court did not like his book. Soon after it was published, Cecil had the book banned on May 14, 1590. Smythe was very upset. He wrote many letters to Cecil, complaining about his financial problems and how he felt ignored in politics. He believed people were against him because of who he was, not because of his book. Smythe tried to publish a corrected version, but Cecil still did not approve it. The book was not printed again until 1964.

Despite its short original print run, Certain Discourses is now seen as a very important and original military book from that time.

Imprisonment and Death (1596–1607)

Smythe's social standing did not improve. By 1596, he had to sell his family estate. On June 12, 1596, Smythe visited his friend Thomas Lucas in Colchester. Smythe went to a field where Lucas's men were training. He began to give speeches, telling them not to waste their lives in foreign wars. He spoke against forcing men into service. He also told them not to follow any orders from Cecil, whom he criticized. Instead, he urged them to follow his nephew, Thomas Seymour.

Smythe's speeches likely resonated with some soldiers. Many were worried about being forced to fight in ongoing wars. However, his support quickly faded. Soon after, Cecil ordered Smythe's arrest, and Lucas cooperated.

Cecil believed Smythe's actions were part of a larger plan. A search of Smythe's house found weapons and writings against Cecil. This was seen as proof of a conspiracy. Smythe was sent to the Tower of London. While imprisoned, Smythe wrote many letters to Cecil. He begged for his release, saying he was sorry. He also threatened to tell people not to fight in foreign wars. As his imprisonment continued, he became less demanding. He mentioned his old age and poor health. Cecil showed some kindness, allowing his wife, lawyer, and a doctor to visit him. Smythe was released from the Tower on February 3, 1598, by the Queen's orders. He was placed under house arrest at his new home in Little Baddow. He also had to make a public apology in Colchester.

After his release, Smythe stayed out of public life. His name does not appear in records until March 4, 1600. Cecil's son, Robert, 1st Earl of Salisbury, asked Smythe for documents about the Inquisition from his time as ambassador. There was no bad feeling between them. A few weeks later, Smythe's house arrest rules were relaxed. He was allowed to travel a bit further from his home. Smythe spent the last seven years of his life quietly at Little Baddow. He died at the end of August 1607 and was buried in the village church.

Sources

- Coros, D. F. (1982). "SMITH, Clement (by 1515-52), of Little Baddow and Rivenhall, Essex.". The House of Commons 1509-1558. The History of Parliament Trust.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |