Slavey language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Slavey |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North: Sahtúgot’įné Yatı̨́ K’ashógot’įne Goxedǝ́ Shíhgot’įne Yatı̨́ South: Dené Dháh, Dene Yatıé or Dene Zhatıé |

||||

| Native to | Denendeh, Canada | |||

| Region | Northwest Territories | |||

| Ethnicity | Slavey, Sahtu | |||

| Native speakers | 2,120, 65% of ethnic population (2016 census) | |||

| Language family | ||||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in | Northwest Territories, Canada | |||

|

||||

|

||||

Slavey (pronounced SLAY-vee) is a group of languages spoken by the Dene people in Canada. These languages are part of the Athabaskan language family. You can find Slavey speakers mainly in the Northwest Territories, where Slavey is an official language.

People write Slavey using a changed Latin writing system. Some also use Canadian Aboriginal syllabics, which are special symbols for sounds. In their own languages, the Slavey languages have different names. In the North, they are called Sahtúgot’įné Yatı̨́, K’ashógot’įne Goxedǝ́, and Shíhgot’įne Yatı̨́. In the South, they are known as Dené Dháh, Dene Yatıé, or Dene Zhatıé.

Contents

- Understanding North and South Slavey

- How Slavey Sounds

- Writing Slavey

- How Slavey Words Are Built

- People, Numbers, and Objects in Slavey

- Classifying Objects in Slavey

- Word Order in Slavey

- No Cases in Slavey

- Showing Ownership (Possessives)

- Slavey Language Status Today

- Slavey in Popular Culture

- Images for kids

Understanding North and South Slavey

The Slavey language is divided into two main groups: North Slavey and South Slavey. These groups are like different versions of the same language.

North Slavey: The Northern Dialect

North Slavey is spoken by the Sahtu Dene people. They live along the middle Mackenzie River, around Great Bear Lake, and in the Mackenzie Mountains. About 800 people speak North Slavey.

North Slavey is actually a mix of three different ways of speaking, called dialects:

- K’ashógot’įne Goxedǝ́: This is the Hare dialect. The people who speak it are sometimes called "Rabbitskin People" because they used to rely on rabbits for food and clothes.

- Sahtúgot’įné Yatı̨́: This is the Bear Lake dialect. It's spoken by the "Bear Lake People" who live near Great Bear Lake.

- Shíhgot’įne Yatı̨́: This is the Mountain dialect. It's spoken by the "Mountain People" who live in the mountains west of other Slavey groups.

South Slavey: The Southern Dialect

South Slavey is spoken by the Slavey people. They live near Great Slave Lake, the upper Mackenzie River, and in parts of northeast Alberta and northwest British Columbia.

Some communities are bilingual, meaning children learn Slavey at home and English at school. In other places, people speak only Slavey. Around 1,000 people speak South Slavey.

The different ways Slavey is spoken are mostly based on how certain old sounds are pronounced.

How Slavey Sounds

Slavey has a range of sounds, including special ones called "tones."

Tones: The Musical Part of Slavey

Slavey uses two main tones:

- High tone

- Low tone

These tones are like the musical pitch of your voice. They can change the meaning of a word. For example, the word for 'along' might sound different from the word for 'rabbit' just because of the tone. In writing, a high tone is shown with a mark like this: ´ (an acute accent). A low tone has no special mark.

Writing Slavey

Slavey has its own alphabet, which helps people write down the language. The alphabet has special letters to show unique sounds.

| a | c | ch’ | d | ddh | dh | dl | dz | e | g | gh | j | i | j | k | k’ | l | ł | m | mb | n |

| nd | o | r | s | sh | t | th | tł | tł’ | ts | ts’ | tth | tth’ | t’ | u | w | y | z | zh | ɂ |

A mark called an "ogonek" (like a small hook under a letter) shows when a vowel sound comes out through the nose.

There are slightly different alphabets for North and South Slavey:

| ɂ | a | b | ch | ch’ | d | dl | dz | e | ǝ | f | g | gh | gw | h | ı | j | k | kw | k’ | kw’ | l | ł |

| m | n | o | p | p’ | r | s | sh | t | t’ | tł | tł’ | ts | ts’ | u | v | w | wh | w’ | x | y | z | zh |

| ɂ | a | b | ch | ch’ | d | dh | ddh | dl | dz | e | f | g | gh | h | ı | j | k | k’ | l | ł | m | mb | n |

| nd | o | p | p’ | r | s | sh | t | t’ | th | tth | tth’ | tł | tł’ | ts | ts’ | u | v | w | x | y | z | zh |

How Slavey Words Are Built

Slavey verbs (action words) are very complex. They are built by adding many small parts, called "morphemes," in a specific order. The main part of the verb always comes last.

For example, to say "S/he prayed," you combine different parts:

- xa + ya + de + d + h + tí = xayadedhtí

To say "S/he talks," it's simpler:

- go + ∅ (a silent part) + deeh = godee

People, Numbers, and Objects in Slavey

Slavey has ways to show who is doing something, how many, and what kind of object is involved.

Gender: Describing Objects

Slavey uses special prefixes on verbs to describe the type of object. There are three main types, or "genders":

- One type is for things that mark a location, like a house or land. For example, kú̜e̒ godetl’e̒h means "S/he is painting the house."

- Another type is for wood, leaves, and branches. For example, tse de̜la means "wood is located."

- The third type has no special prefix.

Number: How Many?

Slavey shows if there are two people or many people.

- If there are two, a prefix like łe̒h- is used. For example, ni̒łe̒gehtthe means "They two got stuck."

- If there are many, the prefix go- is used. For example, Dahgogehthe means "They dance."

Person: Who is Doing It?

Slavey has ways to show if it's "I," "you," "he/she," or "they."

- "I" (first-person singular) uses se-.

- "You" (second-person singular) uses ne-.

- "He/she" (third person) uses be- or me-.

- There's also a "fourth person" (like "his/her own") which uses ye-.

Classifying Objects in Slavey

Slavey has a unique way of classifying objects. It uses five main categories to describe what an object is like. Some categories are even broken down further.

| Class | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | Thin, stiff, long objects | gun, canoe, pencil |

| 1b | Flexible, rope-like objects; groups of things | thread, snowshoes, rope |

| 2a | Flat, flexible objects | open blanket, open tent, paper |

| 3 | Round, chunky objects | ball, rock, stove, loaf of bread |

| 4a | Small containers with contents | pot of coffee, cup of tea |

| 4b | Large containers with contents | full gas tank, bucket of water |

| 5 | Living things | Any living thing |

For example, tewhehchú means "A cloth-like object is in the water." The word part -chú tells you it's a flat, flexible object.

Word Order in Slavey

In Slavey, the verb (the action word) usually comes at the end of the sentence. The basic order is Subject-Object-Verb (SOV).

- Dene ?elá thehtsi̜̒ means "The man made the boat." (Man - boat - made)

- tli̜ ts’ǫ̀dani káyi̜̒ta means "The dog bit the child." (Dog - child - bit)

If there are other objects (like "for her mother"), they come before the direct object.

No Cases in Slavey

Unlike some languages that use special endings on words to show if they are the subject or object, Slavey does not. It uses word order to tell the difference. The first noun is usually the subject, and the noun right before the verb is the direct object.

Showing Ownership (Possessives)

Slavey uses prefixes to show who owns something. These prefixes are similar to the ones used for direct and indirect objects.

- se- means "my":

- sebáré means "my mitts"

- ne- means "your" (singular, for one person):

- net'saré means "your hat"

- be-/me- means "his/her":

- melįé nátla means "His/her dog is fast."

- ye- means "his/her own" (fourth person):

- yekée whehtsį means "S/he made his/her slippers."

- ʔe- means "someone's" (unspecified owner):

- ʔelįé means "someone's dog"

- naxe-/raxe- means "our" or "your" (plural, for many people):

- naxets'éré means "our blanket"

- ku-/ki-/go- means "their":

- kulí̜é rała means "Their dog is fast."

Slavey Language Status Today

North and South Slavey are official languages in the Northwest Territories. This means they can be used in courts and in the government. However, laws and documents are usually only published in Slavey if the government specifically asks for it.

In 2015, a Slavey woman named Andrea Heron faced a challenge. The government would not allow the special character ʔ (which represents a sound called a glottal stop) in her daughter's name, Sakaeʔah. This was despite Slavey being an official language. The government said their documents couldn't handle the character. Ms. Heron joined another woman who had a similar problem with her daughter's name.

Also in 2015, the University of Victoria started a program to help bring back Indigenous languages, including Slavey. The program connects people who want to learn with fluent speakers. They spend many hours talking only in the language, with no English allowed.

Slavey in Popular Culture

Slavey was the language spoken by the fictional band in the Canadian TV show North of 60. Nick Sibbeston, who used to be the leader of the Northwest Territories, helped the show by advising on the Slavey language and culture.

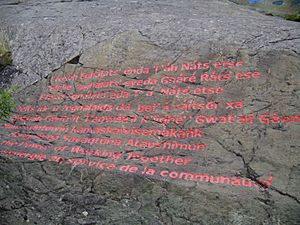

Images for kids

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |