Social War (91–87 BC) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Social War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crisis of the Roman Republic | |||||||

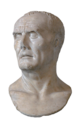

Roman territory in red. Initial insurgent territories in dark green, with later insurgents' territories in light green. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Italian rebels

Marsic group:

Marsi

Paeligni Vestini Marrucini Picentes Frentani |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 175,000 men | 130,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 50,000 killed | 50,000 killed | ||||||

| c. 100,000 killed in total | |||||||

The Social War was a big conflict in ancient Italy. It happened from 91 to 87 BC. This war was fought between the powerful Roman Republic and many of its Italian allies. The word "Social" comes from the Latin word socii, which means "allies." So, it was truly a "War of the Allies." It is also sometimes called the Italian War or the Marsic War.

The war began in late 91 BC when the city of Asculum rebelled. Other Italian towns quickly joined the fight against Rome. At first, Rome was confused about how to respond. But soon, they gathered huge armies to stop the rebels. The fighting was tough, but by the end of the first year, Rome managed to split the Italian rebels into two groups.

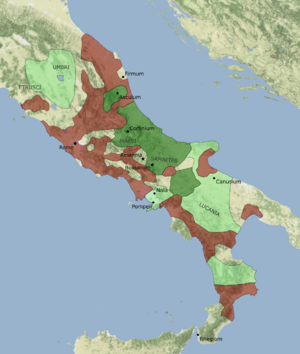

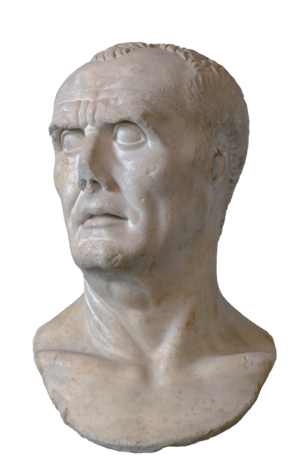

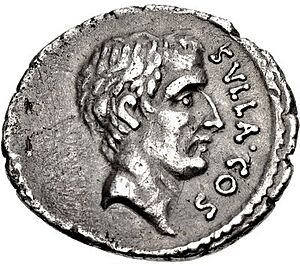

In 89 BC, the Italian rebels tried to invade other Roman areas but were defeated. A Roman general named Lucius Cornelius Sulla won important victories in the south. These wins helped him become a consul the next year. By 88 BC, most of the fighting was over. Rome then focused on another big war in the east. The last rebels made a deal with Rome during a short civil war in 87 BC.

During the war, Rome passed laws offering Roman citizenship to Italian towns. This was if they had not rebelled or if they agreed to stop fighting. This helped to reduce support for the rebels. Historians still debate why the war started. Some think the allies wanted Roman citizenship. Others believe they were fighting against Rome's control over their lands.

Contents

What Was the Social War?

The name Social War comes from the Latin words bellum sociale. This means "war of the allies." Today, this name is used for any war between allies. The historian Florus first used this name in the 2nd century AD. Before that, Romans called it the Marsic War. This was named after the Marsi tribe, who were fierce fighters. They killed two Roman consuls during the war. It was also called the Italian War.

Why Did the War Start?

Italy Before the War

In the 2nd century BC, the Roman Republic controlled the Italian peninsula. Rome had many agreements with city-states in Italy. These cities promised to send soldiers to help Rome in its wars. In return, Rome guaranteed their land and self-government. Italian soldiers became very important to Rome's army. By 218 BC, there were three Italian allies for every two Romans in the army.

Italian cities helped Rome for different reasons. They shared in war treasures and land. Rome also supported the leaders of allied cities against local revolts. Over time, Rome started to get involved in the allies' internal matters. For example, Rome tried to stop certain religious practices in 186 BC.

Before the Social War, people could only have one citizenship. If someone became a Roman citizen, they lost their local citizenship. This meant they might lose their social standing in their hometown.

Italian Demands

Historians still discuss what the Italian allies truly wanted. There are two main ideas from ancient writings. One says they fought for Roman citizenship. The other says they fought against Rome's control.

Edward Bispham, a modern historian, believes the war was a revolt against Rome. He thinks the desire for citizenship and independence both came from a wish for equality and freedom.

Wanting Citizenship

Appian's Civil Wars is a main source for this time. Appian says the Italians wanted Roman citizenship. He also suggests they wanted to be "partners in rule rather than subjects." This means they wanted to share power with Rome. Poorer Italians probably wanted fair treatment from Roman officials. Richer Italians wanted to be directly involved in Roman politics.

Attempts to give citizenship to Italians started in 125 BC. These efforts were often made by Roman politicians. They thought giving citizenship would make Italian leaders happy. This was especially true if Rome needed to use allied lands for its own citizens.

Marcus Livius Drusus, a Roman politician in 91 BC, also tried to pass reforms. These reforms would have given citizenship to the allies. When his plans failed, Appian says the Italians went to war. They wanted the citizenship and legal equality they were denied.

Fighting for Freedom

Henrik Mouritsen, another historian, thinks Appian's idea about citizenship is not quite right. He believes that later writers thought citizenship was very important. They then assumed Italians in the past felt the same way. Mouritsen points out that before the Social War, there was little demand for citizenship. This is because having Roman citizenship meant giving up local independence.

Instead, Mouritsen focuses on Italian anger about Roman land reforms. Rome had taken land from Italian cities centuries ago. After 133 BC, Rome started to divide up these lands. Italians complained that Roman officials were taking their land. This land was supposed to be protected by treaties. These complaints stopped the land distribution process.

Mouritsen suggests that the war started because of these land issues. Drusus proposed a law to give more land to Roman citizens. This angered the allies, who saw their lands being taken. The allies began to prepare for a revolt in 91 BC. Rome sent troops to Italy, which were captured at the start of the war. Drusus then tried to give citizenship to the allies to calm them. When this failed, the war began.

How the War Began

Planning the Revolt

Rebelling against Rome was very risky. The Italians had to form strong alliances. They also exchanged hostages to make sure cities stayed loyal. Appian describes secret talks between Italian states. Rome did not know the full extent of these plans.

Rome was aware of some unrest. Roman troops were sent to important locations before the war. These troops were captured when the war started. This shows that the revolt was planned before Drusus' time in office.

Italian Leadership

When the war began, the Italians quickly formed armies. This means they had already agreed on how to share power. According to ancient sources, the Italians set up a new capital at Corfinium. They created a senate with 500 members. This senate then chose two consuls and twelve praetors. These leaders were split between the northern and southern fighting fronts. Quintus Poppaedius Silo led the north, and Gaius Papius Mutilus led the south.

Some historians think the Italian government was like Rome's. Others believe it was a federal system, with leaders from different tribes. Italian coins and other sources mention "imperatores," which were military commanders. These leaders were likely chosen by each ethnic group.

The Spark of War

In late 91 or early 90 BC, a rumor spread that Asculum was exchanging hostages. This was a sign of war preparations. A Roman official, Quintus Servilius, went to Asculum. He threatened violence if they did not stop. But the people of Asculum were afraid of being discovered. They killed Servilius and another Roman official. They also killed all Romans in the city and took their goods. After this open act of violence, the Italians revolted.

This story is different from Appian's account. Appian says Asculum rioted after Marcus Livius Drusus was killed in Rome. He also says Romans started prosecuting Italians who helped them get citizenship. But historians believe Appian's timeline is wrong. The Italians would not have had enough time to organize after Drusus' death.

The War's Progress

The war's end is not clear. Most fighting stopped in 89 BC. But some rebels continued until 87 BC. There were two main areas of fighting: a northern front and a southern front. There was also a quick attempt to rebel in other areas, but Rome stopped it fast.

At first, Rome was confused by the rebellion. A Roman politician, Quintus Varius Hybrida, set up a court. This court looked for people who had encouraged the Italians to go to war. It seems Romans did not fully understand why the war started.

90 BC: Early Battles

Appian says the Italians gathered about 100,000 men at the start of the war. Rome's Latin allies stayed loyal. Rome also controlled important areas like Capua. The Roman consuls for 90 BC were Lucius Julius Caesar and Publius Rutilius Lupus. They had experienced generals like Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla working for them.

Rome raised a huge army of over 140,000 men. They had fourteen legions. Rome also got ships and soldiers from its allies overseas.

Italian Attacks

The Italians launched their first attacks in late 91 and early 90 BC. Their plans showed they knew Roman military strategies. In the south, the Italian general Gaius Papius Mutilus was merciful to pro-Roman fighters. Many Roman soldiers even switched sides to join the Italians.

The Italian army besieged the Roman colony of Aesernia. Consul Lucius Julius Caesar tried to help but failed. The Romans lost other towns like Venafrum and Grumentum. The Italians won major victories in Campania and Picenum. Mutilus captured several cities in Campania. In Picenum, Italian generals defeated Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo.

Roman Comeback

In the north, on June 11, Consul Publius Rutilius Lupus was killed in battle. His untrained men were defeated by the Marsi. When the bodies were sent back to Rome, it caused panic. The Senate then ordered that war dead be buried on the battlefield.

In the same battle, Gaius Marius won a big victory. He crossed the river after seeing the bodies of Roman soldiers floating downstream. Marius eventually took command. With help from Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Marius defeated the Marsi near the Fucine lake. This victory split the Italian rebels into two groups.

Sextus Julius Caesar helped Pompey Strabo. They defeated the Italian forces and forced them into Asculum. Strabo then besieged Asculum. Sextus' forces also pushed back other Italian armies. The northern front of the war mostly collapsed after these Roman victories.

The Italians tried to negotiate peace. They even asked Mithridates VI Eupator, a king from the east, for help. But Mithridates did not give a clear answer. As Rome gained control, the Senate passed a law. This law, called the lex Julia de civitate, offered Roman citizenship to any Italian community that had not rebelled or that stopped fighting. This law removed a main reason for the war. Only the most determined Italian rebels kept fighting.

89 BC: Roman Victories

The new consuls for 89 BC were Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo and Lucius Porcius Cato. In January, the Marsi tried to support other rebellions. The two consuls stopped them. Strabo defeated the Marsi near Asculum. Cato defeated the Marsi near the Fucine lake but was killed in battle.

The Romans continued to attack the Marsi. They forced the Marsi to ask for peace. These victories allowed Rome to focus on the siege of Asculum. They also could attack the southern Italian forces from the north. The Italians had to move their capital from Corfinium to Bovianum. By summer, Rome had calmed the northern area, except for Asculum.

Rome also attacked in the south. Sulla besieged Nola and captured Pompeii. He also took Stabiae and Herculaneum by June. Sulla then moved into Samnium. He captured Bovianum after tough fighting. The Italians had to move their capital again to Aesernia. Sulla's victories helped him become consul for 88 BC.

Asculum surrendered in November 89 BC. For this victory, Pompey Strabo celebrated a triumph in Rome. More laws were passed to give citizenship, like the lex Plautia Papiria. New laws also helped create new Roman colonies. This process of reorganizing Italy continued for many years.

88 and 87 BC: The End of the War

By 88 BC, the Social War was mostly over. Only a few groups continued to resist. The new consuls were Lucius Cornelius Sulla and Quintus Pompeius Rufus. Rome was worried about Mithridates VI Eupator invading in the east. So, neither consul was sent to fight the Italians. Sulla was given command against Mithridates.

Pompey Strabo continued to accept surrenders in the north. This ended the war in that area. The remaining northern rebels fled south to Samnium and Apulia. The Italians reorganized under Quintus Poppaedius Silo. He commanded about 50,000 men. Silo was able to win back some areas in Samnium. But his forces were badly defeated in Apulia, and Silo was killed.

After Silo's death, Italian organized resistance collapsed. For some historians, his death marks the end of the Social War. However, some Samnite and Lucanian rebels continued fighting. They even asked Mithridates for help. These rebels refused to surrender. In 87 BC, a short civil war broke out in Rome. This allowed the rebels to make a deal with the Roman government. They sided with the Roman general Lucius Cornelius Cinna and Gaius Marius. In return, they were promised citizenship and the return of their people and goods.

What Happened After the War?

The Social War was a huge effort for both sides. Rome had to spend a lot of money on the war. The central and southern parts of Italy were greatly damaged. After the war, much of the Italian countryside was in chaos.

The war changed Italy's political and legal maps. Many Italian communities became Roman citizen cities, called municipia. Their local laws were replaced by Roman laws. This process of making cities Roman took many years.

New Citizens and Voting

One big issue after the war was how to register the new Italian citizens. Rome had 35 tribes, which were voting groups. Each tribe got one vote, no matter how many people were in it. How the many new Italian citizens were placed into these tribes would affect Roman politics for a long time.

At first, there were ideas to create new tribes just for the Italians. This would limit their political power. But a Roman politician named Publius Sulpicius Rufus challenged this. He passed a law to put the new citizens into the existing 35 tribes. This would give them more influence. However, Sulla marched on Rome and canceled this law.

Later, Lucius Cornelius Cinna took control of Rome. He supported the Italians getting full voting rights. He made sure the new citizens were spread among the old tribes. This was confirmed even after Sulla's civil war. But registering all these new citizens took many years. It was not fully completed until the time of Emperor Augustus.

Most new citizens lived far from Rome. Only a few could travel to vote in person. This meant that wealthy people closer to Rome had more influence.

Changes to the Republic

The Social War led to more conflicts. The disputes over citizenship continued. This encouraged people to support generals like Lucius Cornelius Cinna. He presented himself as a champion for the Italians.

The war also changed Roman politics. It brought large armies back to Italy. This gave generals a chance to gain political power illegally. For example, Sulla used his army to take control of Rome in 88 BC.

The war also affected the Roman army. Soldiers' loyalty to the state decreased. Generals had to tolerate bad behavior to keep their men's support. The war also blurred the line between Romans and foreign enemies. Some historians believe that Rome's victory in the Social War was not a true win. It created conditions that led to the collapse of the Roman Republic.

Images for kids

-

Italian coin depicting a soldier standing next to an Italian bull and on top of a Roman standard.

-

Coin depicting Mithridates VI Eupator. On the right, it displays in Greek, his title as basileos, followed by his name. His invasion of Roman Asia in 89 BC triggered the First Mithridatic War.

-

This bronze tablet contains the lex Malacitana, a 1st century AD municipal charter for Malaca – modern Málaga – in Spain. Similar municipal laws, predecessors to the later Flavian-era laws, would have been drawn up through Italy in the aftermath of the war.

-

Gaetano De Sanctis brought a similar view as that of Mommsen, interpreting Italian war goals in the context of Italian risorgimento.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |