Sulla facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sulla

|

|

|---|---|

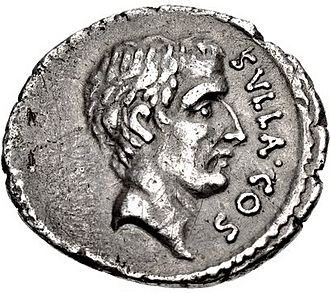

Portrait of Sulla on a denarius minted in 54 BC by his grandson Pompeius Rufus

|

|

| Born | 138 BC |

| Died | 78 BC (aged 60) Puteoli, Italy

|

| Nationality | Roman |

|

Notable credit(s)

|

Constitutional reforms of Sulla |

| Office |

|

| Opponent(s) | Gaius Marius |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children |

|

| Military career | |

| Service years | 107–82 BC |

| Wars | |

| Awards | Grass Crown |

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (138–78 BC), known as Sulla, was a powerful Roman general and statesman. He led the first big civil war in Roman history. He was also the first person in the Republic to take control by force.

Sulla was a very skilled general. He won many battles against enemies both inside and outside Rome. He became famous during the war against King Jugurtha of Numidia. Sulla captured Jugurtha, but his boss, Gaius Marius, got the credit. Sulla then fought successfully against Germanic tribes in the Cimbrian War. He also fought against Italian allies during the Social War. He was given the Grass Crown for his bravery. Sulla believed he was special to the goddess Venus.

Sulla was a key player in the political fights in Rome. He led the optimates, who wanted the Senate to have the most power. They were against the populares, led by Marius, who wanted more power for the common people. Sulla marched his army on Rome, which was unheard of. He defeated Marius's forces. But when Sulla left for Asia, the populares took power again.

Sulla returned from the east in 82 BC. He marched on Rome a second time. He crushed the populares and their allies. He then brought back the job of dictator, which hadn't been used in over a century. He used this power to remove his opponents. He also changed Roman laws to make the Senate stronger. He also limited the power of the tribunes of the plebs. Sulla gave up his dictatorship in 79 BC and retired. He died the next year.

Sulla's actions changed Roman politics forever. His use of the army to gain power set a dangerous example. Later leaders, like Julius Caesar, followed in his footsteps. This led to the end of the Roman Republic.

Contents

Sulla's Early Life and Family

Sulla was born into a noble Roman family called the gens Cornelia. However, his family was not rich when he was born. One of his ancestors, Publius Cornelius Rufinus, was removed from the Senate for having too much silver. After that, Sulla's family didn't hold high offices until Sulla himself.

When Sulla was a baby, a woman supposedly said he would bring luck to his country. After his father died, Sulla was quite poor. He spent his youth with actors and musicians. He even wrote plays. Sulla likely had a good education, learning Greek and Latin. He was fluent in Greek. He became wealthy later in life through inheritances from his stepmother and a friend. This wealth helped him start his political career.

Sulla's First Steps in Politics

Sulla became a quaestor in 108 BC. This was his first official job in Roman politics. A quaestor was a public official who managed money. He was assigned to work under the famous general Gaius Marius.

The War Against Jugurtha (107–106 BC)

The Jugurthine War began in 112 BC. King Jugurtha of Numidia was fighting against Rome. He had killed Roman traders and used bribes. Several Roman commanders had failed against him. In 107 BC, Marius became consul and took over the war. Sulla joined his team.

Marius asked Sulla to organize cavalry (horse soldiers) in Italy. This was a very important job for a young man with little military experience. Sulla was popular with the soldiers. He got along well with other officers, including Marius.

In 106 BC, Sulla helped capture King Jugurtha. Jugurtha had fled to his father-in-law, King Bocchus I of Mauritania. Marius invaded Mauretania. After a big battle, Bocchus decided to betray Jugurtha to the Romans. Sulla was sent to negotiate with Bocchus. He successfully convinced Bocchus to hand over Jugurtha. This made Sulla very famous. Years later, Bocchus even built a statue showing Sulla capturing Jugurtha.

The Cimbrian War (104–101 BC)

In 104 BC, two Germanic tribes, the Cimbri and Teutones, threatened Italy. They had beaten Roman armies before. Marius was elected consul many times to deal with this crisis. Some Roman leaders in the Senate saw Sulla as a way to balance Marius's growing power.

Sulla served under Marius in Gaul. He helped defeat a Gallic tribe that had rebelled. The next year, he was a military tribune. He helped negotiate with the Marsi tribe, convincing them to leave the Cimbri. Sulla felt Marius wasn't giving him enough chances. So, he asked to be transferred to the army of Catulus, Marius's fellow consul.

In 102 BC, the invaders returned. Catulus and Sulla tried to stop them but were defeated. Marius, however, destroyed the Teutones. Marius then joined Catulus's army. Sulla was in charge of getting food for both armies. He did this very well. The Roman armies then attacked the Cimbri. At the Battle of the Raudian Field, the Cimbri were completely defeated.

Marius and Catulus were given triumphs (victory parades). Sulla ran for praetor in 99 BC but lost. People thought he was too proud of his military record for a junior officer. They also knew he was friends with a rich foreign king, Bocchus. They wanted him to spend money on public games. Sulla ran again the next year, promising good shows. He was elected praetor in 97 BC.

Governor in Cilicia (96–93 BC)

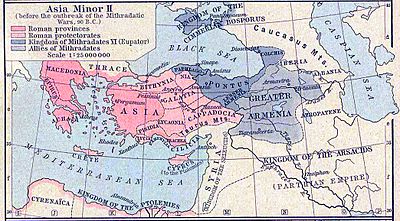

Sulla's time as praetor was mostly quiet. In 96 BC, he became governor of Cilicia in Asia Minor. The Senate ordered Sulla to put Ariobarzanes back on the throne of Cappadocia. King Mithridates VI of Pontus had driven Ariobarzanes out. Sulla succeeded with few Roman troops. He quickly gathered allied soldiers and defeated the enemy. His soldiers were so impressed they called him imperator (a title of honor for a victorious general).

Sulla met with an ambassador from the Parthian Empire near the Euphrates river. This was the first time a Roman official met a Parthian ambassador. Sulla made sure to sit between the Parthian and Cappadocian leaders. This showed that Rome was superior to both. The Parthian ambassador was executed back home for allowing this. But the treaty was agreed upon. It set the Euphrates as the border between Rome and Parthia. A seer told Sulla he would die at the peak of his fame. This prophecy stayed with Sulla his whole life.

Sulla returned to Rome around 92 BC. He was seen as successful in the east. He had restored a king, been hailed imperator, and made a treaty with the Parthians. However, he was accused of taking money from Ariobarzanes. The case was dropped, but it hurt his political plans.

The Social War (91–88 BC)

Relations between Rome and its Italian allies had worsened. The allies wanted Roman citizenship. In 91 BC, a tribune trying to pass a citizenship bill was killed. This caused the Italians to revolt. This was the Social War.

Sulla served as a general in southern Italy. He worked under Consul Lucius Julius Caesar. In the first year, Sulla helped Marius defeat the Marsi. Sulla also tried to help relieve the besieged city of Aesernia, but failed.

In 89 BC, Sulla was put in charge of the southern army. He besieged Pompeii. He defeated an Italian relief force and killed their leader. Sulla then captured Pompeii, Stabiae, and Aeclanum. He forced the Hirpini to surrender. He also attacked the Samnites and captured their capital. For these victories, Sulla was awarded the Grass Crown, Rome's highest military honor.

Rome also passed laws granting citizenship to loyal allies. Sulla's military successes helped end the war. He was easily elected consul for 88 BC. His colleague was Quintus Pompeius Rufus.

Sulla's First Consulship

Sulla's election as consul was a big success. He married his daughter to his colleague Pompeius Rufus's son. He also married Metella, a powerful widow. These marriages helped him build strong political connections.

Sulla passed two laws to help Rome's finances. One law limited interest rates on loans. The other made it easier for poor people to bring debt cases to court. These laws made him popular with the common citizens.

Conflict with Sulpicius

Sulla soon faced a political fight with Publius Sulpicius Rufus, a tribune. Sulpicius wanted to give new Italian citizens more voting power. Sulla and Pompeius Rufus opposed this. Sulpicius then made a secret deal with Marius. Marius would support Sulpicius's law if Sulpicius transferred Sulla's military command to Marius.

Sulpicius tried to pass his law by force. The consuls tried to stop public business. Sulpicius and his armed followers forced the consuls to flee. Sulla had to hide in Marius's house. Marius made Sulla lift the ban on public business. Sulla then left for Capua to join his army.

Sulla Marches on Rome

Sulla learned that Marius had tricked him. Sulpicius passed a law giving Marius command of the war against Mithridates. Sulla told his soldiers that Marius would take away their chance for glory and riches in the East. His troops agreed to follow him to Rome. Most of his officers, however, deserted him.

The Senate and people of Rome were shocked by Sulla's march. Sulla boldly said he was freeing Rome from tyrants. He entered the city and stationed his troops. He then made the Senate declare Marius, his son, Sulpicius, and nine others outlaws. Only Sulpicius was killed. Marius and his son escaped to Africa.

Sulla then cancelled Sulpicius's laws. He tried to strengthen the Senate's power. He sent his army back to Capua. The next elections were a big defeat for Sulla and his allies. His enemy, Lucius Cornelius Cinna, was elected consul. Cinna said he would prosecute Sulla.

Sulla made the new consuls swear to uphold his laws. He then left Italy with his troops for the East. He ignored legal summonses. Sulla's actions showed that military force could be used against Roman citizens. This was a dangerous new step. Political violence continued in Rome after he left. Cinna and Marius eventually took Rome, killed their enemies, and declared Sulla an outlaw. They were then elected consuls.

Sulla's Time as Proconsul

The First Mithridatic War

In 89 BC, King Mithridates VI Eupator of Pontus invaded Roman Asia. Rome declared war. But it took Sulla 18 months to gather his five legions. While Rome prepared, Mithridates ordered the killing of about 80,000 Romans and Italians in Asia.

Mithridates's success caused Athens to revolt against Roman rule. Sulla arrived in Greece in 87 BC. He besieged Athens and its port, Piraeus. These sieges lasted until spring 86 BC.

Sack of Athens

Sulla found a weak spot in Athens' walls. He stormed and captured the city on March 1, 86 BC. The Acropolis was still under siege. Athens was spared total destruction because of its famous past. But the city was looted. Sulla needed money, so he took treasures from temples in Epidaurus, Delphi, and Olympia. After a battle, Sulla's forces captured Piraeus and destroyed it.

Battles in Boeotia

In summer 86 BC, two major battles happened in Boeotia. The Battle of Chaeronea and the Battle of Orchomenus. Sulla's army moved from Athens to central Greece. He needed more food for his soldiers.

At Chaeronea, Sulla's Romans defeated a much larger Pontic army. The Romans stopped the enemy's chariots. They then pushed back the Pontic soldiers. After this victory, Sulla learned that Cinna's government had sent a general to take over his command. Sulla was officially an outlaw in Rome.

Sulla then fought the Pontic army again at Orchomenus. His troops dug trenches to trap the enemy cavalry. Sulla personally rallied his men when they almost broke. The Romans surrounded the Pontic camp and destroyed the army.

Peace with Mithridates

After the battle, Mithridates's general, Archelaus, asked for peace terms. Sulla and Archelaus agreed on terms. Mithridates had to give back Roman lands. He also had to return kingdoms to their rulers. Mithridates would give Sulla ships and pay a large amount of money. In return, Sulla would recognize Mithridates as a Roman ally.

Mithridates was facing rebellions and another Roman army in Asia. He met Sulla in autumn 85 BC and accepted the peace terms. Sulla then dealt with affairs in Asia. He stayed there until 84 BC. He then sailed for Italy with 1,200 ships.

Some people criticized Sulla's peace with Mithridates. They thought he betrayed Roman interests to focus on the civil war in Italy. But later campaigns showed that Mithridates was hard to defeat. Sulla's time in Asia also gave him money and forces for the coming war in Italy.

Civil War in Italy

Sulla landed in Italy in spring 83 BC. He had five legions of experienced soldiers. Many Roman leaders joined him, including Marcus Licinius Crassus and Pompey. Pompey raised an army from his supporters and joined Sulla. Sulla treated him with great respect.

Most people in Italy were against Sulla. They remembered his unpopular actions in Rome. The Senate declared him an enemy. They raised a large army. Sulla, with his money from Asia, advanced quickly. He defeated one of the consuls, Norbanus. He then met the other consul, Scipio. Sulla tried to negotiate with Scipio. Scipio's army blamed him for the talks breaking down. They deserted Scipio and joined Sulla. Sulla let Scipio go.

In 82 BC, the new consuls were Gnaeus Papirius Carbo and the younger Gaius Marius. Sulla faced the younger Marius in the south. Marius, with Samnite support, fought Sulla at Sacriportus. Marius was defeated when some of his soldiers deserted. Marius then retreated to Praeneste and was besieged.

After Marius's defeat, Sulla ordered the killing of Samnite prisoners. This caused more uprisings. Sulla left a general to continue the siege of Praeneste and marched on Rome. The city opened its gates to him. Sulla declared his enemies outlaws. He then left to fight Carbo.

Carbo had suffered defeats. He tried to relieve Marius at Praeneste. Sulla prevented the Italians from helping Marius or Carbo. Carbo lost hope and tried to flee to Africa. His generals tried again to relieve Praeneste. When that failed, they marched on Rome. Sulla rushed back to Rome. He fought the Battle of the Colline Gate on November 1, 82 BC. Sulla's forces won the battle. The civil war in Italy was mostly over.

Sulla's Dictatorship and Reforms

After the Battle of the Colline Gate, Sulla called the Senate to a temple. While he was speaking, he had thousands of Samnite prisoners killed. This shocked the senators. Sulla then went to Praeneste and ended the siege.

Sulla's stepdaughter married Pompey. Pompey was sent to take control of Sicily. With the capture and execution of Carbo, both consuls for 82 BC were dead.

The Proscriptions

Sulla was now in complete control of Rome. He started a program called the proscriptions. This meant he listed people as enemies of the state. These people were then hunted down and killed. Their property was taken by the state.

The proscriptions were Sulla's response to similar killings by Marius and Cinna. Sulla ordered about 1,500 nobles killed. Some estimates say as many as 9,000 people were killed in total. Helping a proscribed person was punishable by death. Killing one was rewarded. Most people killed were not Sulla's enemies. They were killed for their wealth. Their property was sold, which filled Rome's treasury. To protect himself, Sulla banned the sons and grandsons of proscribed people from holding political office. This ban lasted over 30 years.

The young Julius Caesar was a target because he was Cinna's son-in-law. Caesar fled Rome. His relatives, who supported Sulla, helped save him. Sulla later said he regretted sparing Caesar's life. He believed Caesar would become a danger.

Becoming Dictator

At the end of 82 BC or early 81 BC, the Senate appointed Sulla dictator for making laws and settling the constitution. The people's assembly approved this. There was no time limit on his power. Sulla had total control of Rome. This was unusual. Dictators were only appointed in emergencies and for six months. Sulla's dictatorship set a precedent for later leaders like Julius Caesar. It also showed how the Republic could end.

Sulla's Reforms

Sulla wanted to make the Senate stronger. He was an optimate, meaning he supported the traditional Roman aristocracy. He kept his earlier reforms that required Senate approval for new laws. He also made the Centuriate Assembly (assembly of soldiers) more aristocratic.

Sulla disliked the office of the Plebeian Tribune. He believed it was dangerous. He wanted to take away its power and prestige. Tribunes lost the power to propose laws. Sulla also banned former tribunes from holding any other office. This was to stop ambitious people from becoming tribunes. He also took away the tribunes' power to veto Senate actions. However, he kept their power to protect individual Roman citizens.

Sulla increased the number of officials elected each year. He also made all new quaestors automatically become members of the Senate. These changes increased the Senate's size from 300 to 600 members. This also meant the censor no longer needed to create a list of senators. Sulla also gave control of the courts back to the senators. This added to the senators' power.

Sulla also set clear rules for the cursus honorum. This was the order of public offices a Roman politician had to follow. It required a certain age and experience for each office. Sulla also made a rule that a person had to wait 10 years before being re-elected to the same office. He also made sure that consuls and praetors served in Rome during their year in office. Then, they would command a provincial army as a governor the next year. This was to reduce the risk of generals seizing power, like he had done.

Sulla also expanded the Pomerium, the sacred boundary of Rome. This boundary had not changed since the time of the kings. Sulla's reforms looked to the past and also set new rules for the future.

In 80 BC, Sulla resigned his dictatorship. He also disbanded his armies. He walked unguarded in the Forum. He wanted to show that normal government was back. Julius Caesar later made fun of Sulla for giving up his power.

Retirement and Death

Sulla kept his promise and gave up his power. He retired to his country home near Puteoli to be with his family. He stayed out of daily politics in Rome.

Sulla spent his retirement writing his memoirs. He finished them in 78 BC, just before he died. Most of his writings are now lost. Ancient stories say he died from liver failure or a stomach problem.

Sulla had a huge public funeral in Rome. His body was brought into the city on a golden platform. His veteran soldiers escorted it. Many important senators gave speeches. Sulla's body was cremated. His ashes were placed in his tomb in the Campus Martius. Sulla wrote his own epitaph (words on his tomb). It said, "No friend ever served me, and no enemy ever wronged me, whom I have not repaid in full."

Sulla's Impact on Rome

Sulla is often seen as setting a dangerous example for future Roman leaders. Cicero said that Pompey once asked, "If Sulla could, why can't I?" Sulla showed that a general could use his army to take power. This inspired others and helped lead to the end of the Roman Republic.

Sulla tried to make laws to stop generals from using their armies for personal gain. But these laws didn't stop determined generals like Pompey and Julius Caesar. Sulla knew this was a risk.

Many of Sulla's laws lasted for a long time. These included laws about joining the Senate, reforming the legal system, and governing provinces. However, much of his other legislation was cancelled less than ten years after his death. The veto power of the tribunes and their law-making authority were soon brought back. This happened during the consulships of Pompey and Crassus.

Sulla's family continued to be important in Roman politics for many years. His son and grandson issued coins with his name. His descendants held four consulships during the Roman Empire. The last of his direct family line was executed in AD 62 by Emperor Nero.

Sulla's rival, Gnaeus Papirius Carbo, once said Sulla had the cunning of a fox and the courage of a lion. Carbo believed Sulla's cunning was the most dangerous. This idea was later used by Machiavelli to describe an ideal ruler.

Sulla's Family Life

Sulla had five wives and several children:

- His first wife was Ilia (or Julia). They had two children:

- Cornelia, who married twice. Her daughter, Pompeia, later married Julius Caesar.

- Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who died young.

- His second wife was Aelia.

- His third wife was Cloelia, whom Sulla divorced.

- His fourth wife was Caecilia Metella. They had twins:

- Faustus Cornelius Sulla, who was a quaestor.

- Fausta Cornelia, who also married twice.

- His fifth and last wife was Valeria. They had one child:

- Cornelia Postuma, who was born after Sulla's death.

Sulla's Appearance and Personality

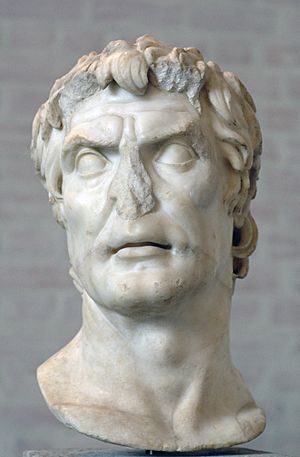

Sulla had red-blond hair, blue eyes, and a pale face with red marks. He thought his golden hair made him look unique.

People said Sulla had two sides to his personality. He could be charming and friendly, joking with common people. But he could also be very strict and serious when leading armies or acting as dictator.

His early life was difficult. He lost his father young and was relatively poor. This might have made him independent. His experiences with ordinary Romans may have helped him succeed as a general, even though he didn't have much military experience until his 30s.

Key Dates in Sulla's Life

- circa 138 BC: Born in Rome.

- 107-105 BC: Served as Quaestor under Gaius Marius in the war against Jugurtha.

- 106 BC: Helped end the Jugurthine War.

- 104-101 BC: Served as a general in the Cimbrian War.

- 97 BC: Became Praetor urbanus.

- 96 BC: Served as governor of Cilicia.

- 90-89 BC: Fought as a senior officer in the Social War.

- 88 BC:

- Became consul for the first time.

- Marched on Rome and declared Marius an outlaw.

- 87 BC: Led Roman armies against King Mithridates of Pontus.

- 86 BC: Participated in the sack of Athens and won the Battle of Chaeronea and the battle of Orchomenus.

- 85 BC: Freed the provinces of Macedonia, Asia, and Cilicia from Pontic control.

- 84 BC: Reorganized the province of Asia.

- 83 BC: Returned to Italy and began a civil war against Marius's supporters.

- 82 BC: Won the Battle of the Colline Gate, ending the civil war.

- 82/81 BC: Appointed dictator.

- 80 BC: Served as consul for the second time. Resigned his dictatorship.

- 79 BC: Retired from political life.

- 78 BC: Died in Puteoli.

See also

In Spanish: Sila para niños

In Spanish: Sila para niños

- Apellicon of Teos

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |