Southern Rhodesia in World War II facts for kids

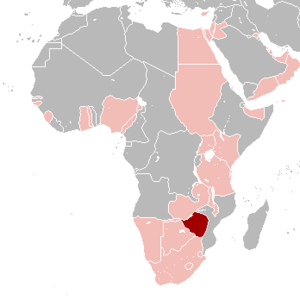

Southern Rhodesia, a self-governing British colony (now Zimbabwe), joined World War II in 1939. This happened right after Germany invaded Poland, and Britain declared war. Even though it was a colony, Southern Rhodesia managed its own contributions to the war.

Many Southern Rhodesians served in the armed forces. A total of 26,121 people, from all races, joined up. About 8,390 of them served overseas. They fought in Europe, the Mediterranean, East Africa, and Burma.

One of Southern Rhodesia's most important contributions was to the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. This plan trained airmen from Britain, the Commonwealth, and other Allied countries. Southern Rhodesia trained 8,235 airmen in its flying schools.

Sadly, 916 Southern Rhodesians were killed and 483 were wounded during the war.

Rhodesian soldiers were spread out among British and South African forces. This was done to avoid large losses in any single unit. Most white Rhodesian men served in Britain, East Africa, and the Mediterranean. Later in the war, they were sent to more places. Black troops, mainly from the Rhodesian African Rifles, fought in Burma from late 1944. Other non-white soldiers and white servicewomen helped in East Africa and at home in Southern Rhodesia.

Thousands of black men were also asked to work. They helped build airfields and later worked on farms.

World War II changed Southern Rhodesia a lot. It affected its money and military. The air training scheme especially helped the economy and led to many former airmen moving to Southern Rhodesia after the war. This made the white population more than double by 1951.

After Zimbabwe became independent in 1980, the government removed many war memorials. They saw them as reminders of colonial rule.

Contents

How the War Started for Southern Rhodesia

In 1939, Southern Rhodesia had been a self-governing colony for 16 years. This meant it had a lot of power over its own affairs, including defense. However, it was not fully independent like a "dominion" (countries like Canada or Australia). Still, it was often treated like one by other Commonwealth nations.

In 1939, Southern Rhodesia had about 67,000 white people. This was a small group, about 5% of the total population. The black population was over a million. There were also about 10,000 people of mixed or Indian heritage.

The leader of Southern Rhodesia was Godfrey Huggins. He had been Prime Minister since 1933. He had also fought in World War I.

Before World War II, Southern Rhodesia had a small army called the Rhodesia Regiment. It was made up of white men. There was also the British South Africa Police (BSAP), which was partly military. The Rhodesian Air Force (SRAF) was very small, with only 10 pilots and eight planes.

When Nazi Germany took over Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Huggins knew war was coming. He wanted to make sure his government could pass emergency laws. He decided to spread Rhodesian soldiers in small groups among British and South African forces. This was to prevent huge losses, like those seen in World War I. This idea was approved.

Southern Rhodesia would automatically be included if Britain declared war. But the colony still showed its loyalty. On August 28, 1939, its parliament voted to support Britain if war broke out.

War Begins

When Britain declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939, Southern Rhodesia declared war almost immediately. This was even before some of the fully independent dominions did. Huggins said the war was about survival for Southern Rhodesia, just as it was for Britain.

Most white people supported this decision. They felt it was their patriotic duty. Most black people did not pay much attention to the war starting.

Britain expected Italy to join Germany, but this did not happen right away. Southern Rhodesia's No. 1 Squadron SRAF was already in northern Kenya, near the Italian East Africa border.

The first Rhodesian ground troops sent overseas were 50 soldiers. They went to Nyasaland in September to guard against a possible uprising. They returned after a month. White Rhodesian officers also went to other parts of Africa to lead black troops there. This became a common practice.

Many white Rhodesians volunteered for the forces very quickly. Over 2,700 joined in the first three weeks. The main problem for recruiters was convincing men in important jobs, like mining, to stay home.

The SRAF accepted 500 new recruits. Its commander offered to run a flying school to train more airmen. This offer was accepted. In January 1940, Southern Rhodesia set up its own Air Ministry. This ministry would manage the Rhodesian Air Training Group, which was part of the larger Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS).

By May 1940, about 1,600 white Rhodesians were serving overseas. Southern Rhodesia passed a law allowing the call-up of white men aged 19 to 25. The age was later lowered to 18. Part-time training became mandatory for all white men aged 18 to 55.

On May 25, 1940, Southern Rhodesia became the first country in the EATS to start an air school. The SRAF became part of the British Royal Air Force (RAF) in April 1940. Two other RAF squadrons were later named "Rhodesian" squadrons.

Fighting in Africa and the Mediterranean

First Deployments

No. 237 Squadron was based in Kenya. By March 1940, it had grown to 28 officers and 209 other ranks. Many Rhodesian officers and men were in Kenya, helping different East African units. Rhodesian surveyors mapped areas near Abyssinia and Italian Somaliland. The Medical Corps ran a hospital in Nairobi. A company of coloured and Indian-Rhodesian transport drivers also arrived in Kenya in January.

The first large group of white Rhodesian soldiers went to North Africa and the Middle East in April 1940. They were 700 men from the Rhodesia Regiment. They joined various British units in Egypt and Palestine. Many Rhodesian soldiers were part of the King's Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC). Rhodesian signallers also worked with the British Royal Corps of Signals.

East Africa Campaign

Italy joined the war on June 10, 1940. This started the East African Campaign and the Desert War in North Africa. Rhodesian-led forces were involved in early clashes with Italian troops.

Italian forces invaded British Somaliland on August 4, 1940. A British force, including 43 Rhodesians, fought the Italians at the Battle of Tug Argan. The British had to retreat and were evacuated by sea. The Italians then took over British Somaliland.

No. 237 Squadron flew reconnaissance missions and supported ground attacks on Italian outposts. British forces in Kenya grew stronger with the arrival of South African brigades. No. 237 Squadron moved to Sudan in September.

In Sudan, No. 237 Squadron continued reconnaissance and bombing missions. The Southern Rhodesian Anti-Tank Battery arrived in Kenya in October. They joined the front lines in January 1941.

British forces, including Rhodesian officers, advanced into Abyssinia and Italian Somaliland in early 1941. No. 237 Squadron supported Indian divisions in Eritrea. One Rhodesian plane was shot down. Italian fighters also attacked Rhodesian planes on the ground.

The Battle of Keren (February–April 1941) was a tough, seven-week fight. No. 237 Squadron helped by observing Italian positions and bombing. After the Italians surrendered, the Rhodesian squadron moved to Asmara. They bombed the port of Massawa. On the same day, the Italian capital of Abyssinia, Addis Ababa, surrendered. The war in East Africa effectively ended when the Duke of Aosta surrendered on May 18, 1941. No. 237 Squadron and the Rhodesian Anti-Tank Battery then moved to Egypt to fight in the Western Desert.

North Africa Campaign

In North Africa, Rhodesians helped in Operation Compass (December 1940 – February 1941). They fought at Sidi Barrani, Bardia, and other places. This operation was very successful for the Allies. They captured Tobruk and many Italian soldiers. Germany sent the Afrika Korps under Erwin Rommel to help the Italians. Rommel then launched a strong counter-attack, forcing the Allies to retreat.

Many Rhodesian soldiers were transferred to Kenya in February 1941 to join the new Southern Rhodesian Reconnaissance Regiment. Rhodesians in the 1st Cheshires moved to Malta. The Rhodesian Signallers went to Cairo to handle communications. The 2nd Black Watch, with its Rhodesian soldiers, defended Crete and later joined the Tobruk garrison. No. 237 (Rhodesia) Squadron received new Hawker Hurricane planes.

Rhodesians were also a key part of the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG). This unit operated behind enemy lines. It was formed in 1940. By late 1941, there were two Rhodesian patrols in the LRDG. Each vehicle had a Rhodesian place-name on its hood. The LRDG worked closely with the Special Air Service (SAS), which also had some Rhodesians. They transported and supported SAS troops. The LRDG also kept a "Road Watch" on the main road in Libya, reporting enemy movements.

In November 1941, the British Eighth Army launched Operation Crusader to relieve Tobruk. Rhodesians in the LRDG raided enemy areas, ambushing convoys and destroying aircraft.

Rommel advanced east in January 1942. He won a major victory at the Battle of Gazala in May–June 1942, and captured Tobruk. During this time, the Southern Rhodesian Anti-Tank Battery suffered losses. Rommel's advance was stopped at the First Battle of El Alamein in July.

Southern Rhodesian pilots also helped defend Malta in 1942. John Plagis, a Rhodesian airman, became a "flying ace" by shooting down five enemy planes.

In late 1942, Southern Rhodesia decided to join a unified Southern African Command led by South Africa. This meant most Rhodesian servicemen would fight alongside South African forces for the rest of the war.

El Alamein Battle

The Second Battle of El Alamein (October–November 1942) was a major victory for the Allies. It changed the course of the North African war. Rhodesians in the KRRC were part of the initial attack.

The Rhodesian Anti-Tank Battery also fought at El Alamein. They supported the Australian 9th Division. The fighting was very intense. The Rhodesian gunners disabled two German tanks and damaged two more, forcing the enemy to retreat. They held their position. One Rhodesian officer and seven other ranks were killed. Several Rhodesians received medals for their bravery.

After El Alamein, the KRRC Rhodesians chased the retreating Axis forces. They advanced through Tobruk, Gazala, and Benghazi. By January 1943, Allied forces reached Tunisia's border.

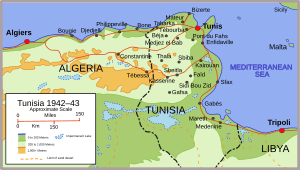

Tunisia Campaign

The Tunisia Campaign had two fronts. The Eighth Army, including Rhodesian units, was in southeastern Tunisia. The Germans attacked Medinine in March 1943, but failed. No. 237 (Rhodesia) Squadron, with future Prime Minister Ian Smith as a pilot, returned to North Africa.

Montgomery launched a major attack on the Mareth Line on March 16. The Rhodesian Anti-Tank Battery took part. The Allies advanced, but bad weather slowed them down. A flanking move by New Zealand forces forced the Axis to withdraw. The Rhodesian anti-tank gunners fought their last battle in Africa at Enfidaville on April 20. British tanks entered Tunis on May 7, 1943. The Axis forces in North Africa surrendered a week later.

By the time Tunis fell, most Rhodesians were moving to the South African 6th Armoured Division or going home on leave.

Dodecanese Islands Campaign

The Long Range Desert Group (LRDG), which included Rhodesians, fought in the Dodecanese Campaign (September–November 1943). They were sent to the island of Kalymnos. The Allies were trying to capture these islands to use them as bases against German-occupied areas.

The Germans launched heavy air attacks. The LRDG and other troops on Kalymnos had to withdraw to Leros. German air attacks on Leros increased. On November 12, 1943, the Germans attacked Leros by sea and air. During the Battle of Leros, Rhodesians fought bravely. They held their position for three days. On November 16, they were ordered to split up and escape. More than half of the unit made it back to Egypt.

Italy Campaign

The largest group of Southern Rhodesian troops in the Italian Campaign (1943–45) was about 1,400 men. They were mostly from the Southern Rhodesian Reconnaissance Regiment and were part of the South African 6th Armoured Division. This division had Rhodesian tank squadrons and a large group of Rhodesian infantry. There were also two Rhodesian artillery batteries.

After training in Egypt, the division sailed to Italy in April 1944. No. 237 Squadron, now flying Spitfires, moved to Corsica to operate over Italy.

The 6th Division helped force the Germans out of the Battle of Monte Cassino in May 1944. They then advanced towards Rome. On June 6, 1944, a Rhodesian tank squadron was among the first Allied units to enter Rome.

The Germans fought hard, slowly retreating north. The mountainous terrain made it difficult for tanks. The Rhodesian tank squadrons fought in victories at Castellana, Bagnoregio, and Chiusi.

By late August 1944, the Germans had formed the Gothic Line in the mountains. The Rhodesians of Prince Alfred's Guard temporarily became infantry. The Southern Rhodesian Anti-Tank Battery also used mortars. They helped push the Germans north.

In October, Rhodesians of the Cape Town Highlanders fought fiercely at Monte Stanco. They suffered heavy losses but achieved their goal. Both Rhodesian artillery batteries supported the attack.

During the winter of 1944–45, the Rhodesians patrolled around the Reno River. Many had never seen snow but adapted well. In February 1945, the 6th Division moved to Lucca for rest. No. 237 Squadron attacked German transport in the Po Valley.

Balkans and Greece

After the Battle of Leros, the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) was reorganized. About 80 of its officers and men were from Southern Rhodesia. In early 1944, the LRDG moved to Italy. Britain wanted to keep German divisions busy in southeastern Europe. In June 1944, the LRDG operated on the coast of Yugoslavia. They set up observation posts and reported German ship movements.

Rhodesian patrols from the LRDG went into Yugoslavia and Albania in August and September 1944. They contacted partisan leaders to arrange air support. From September, Rhodesians from the LRDG also did reconnaissance in southern Greece. They entered Athens in November as the Germans left. The Rhodesians helped Greek forces guard an orphanage in Athens against communist supporters. Four Rhodesians were killed.

The LRDG returned to Yugoslavia in February 1945. They patrolled the coast to find German ships hiding during the day. They reported their locations for bombing. This was dangerous work. Sometimes, Rhodesian patrols communicated in Shona to avoid being understood by Germans. The LRDG's last actions were helping Tito's partisans capture German-held islands in April and May 1945.

Spring 1945 Offensive in Italy

In March 1945, German forces in Italy still held strong defensive positions. The 6th Division rejoined the line in early April, just before the Allies launched their spring offensive. Rhodesian units took positions opposite Monte Sole, Monte Abelle, and Monte Caprara.

On April 15, 1945, South Africans and Rhodesians attacked German positions. The Cape Town Highlanders advanced up Monte Sole. A Rhodesian officer, Second Lieutenant G. B. Mollett, led his men through a minefield to the top. He later received a medal for this. Hand-to-hand fighting continued until dawn, when the Germans retreated. The Witwatersrand Rifles took Monte Caprara. The Cape Town Highlanders took Monte Abelle on April 16. The regiment lost 31 killed and 76 wounded, including three Rhodesians killed.

This victory helped the Allies break through. By April 19, the 6th Division's tanks were moving towards Lombardy and Venetia. American and Polish troops entered Bologna on April 21. The South Africans and Rhodesians advanced northwest. The Rhodesian squadron of the Special Service Battalion and the Rhodesians of Prince Alfred's Guard fought many battles with the retreating Germans.

The 6th Division crossed the Po River on April 25. They then quickly advanced towards Venice. On April 30, the 6th Division met up with British and American forces south of Treviso. They cut off the Germans' last escape route from Italy.

German forces in Italy surrendered on May 2, 1945. The 6th Division was near Milan. Twelve days later, the 6th Division held a victory parade at Monza racetrack. The Rhodesians then served as occupation troops in Lombardy before returning home.

Britain, Norway, and Western Europe

Southern Rhodesia's main fighting contributions in Britain and Western Europe were in the air. Rhodesian pilots and Allied airmen trained in the colony's flying schools helped defend Britain. They also took part in bombing Germany.

Rhodesia had the only RAF flying ace of the Norwegian Campaign (April–June 1940), Squadron Leader Caesar Hull. Later, in the Battle of Britain, three Rhodesian pilots were among "The Few" who defended Britain. Two of them, Hull and John Chomley, died.

Two of the RAF's three Rhodesian squadrons, Nos. 44 and 266, operated from England. No. 266 (Rhodesia) Squadron was a fighter squadron. It was initially mixed but became almost entirely Rhodesian by August 1941. It fought in the Battle of Britain. Its duties included patrolling, protecting convoys, and escorting bombing raids.

No. 44 (Rhodesia) Squadron was a heavy bomber unit. It was the first RAF squadron to use Lancasters. It took part in important attacks, like the one on the MAN diesel factory in Augsburg in April 1942. In March 1943, No. 44 Squadron bombed cities in northern Italy and Germany, including Berlin.

From early 1944, No. 266 Squadron took part in ground attacks over the Channel and northern France. They also escorted Allied bombers. In May 1944, Prime Minister Sir Godfrey Huggins visited the squadron. Before the invasion of Normandy, the Rhodesian aircraft became fighter-bombers. They bombed bridges, roads, and railways.

Southern Rhodesians were also involved in the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944 ("D-Day"). Some served on ships, others parachuted into Normandy. No. 266 Squadron flew over the beaches, supporting the infantry and paratroopers.

No. 266 Squadron, still mostly Rhodesian, supported the advancing Allied armies through France, the Low Countries, and Germany. In late March 1945, Rhodesian fighters protected Allied paratroopers crossing the Rhine. In April, the squadron operated over Hanover and the northern Netherlands. No. 44 Squadron bombed targets as far away as East Prussia and cities closer to Berlin. Its last bombing mission was on Hitler's residence, the Berghof, on April 25, 1945. After Germany surrendered on May 7, No. 44 Squadron helped evacuate British prisoners of war.

Burma Campaign

Southern Rhodesia's main contribution to the Burma Campaign was the Rhodesian African Rifles (RAR). This regiment of black troops, led by white officers, joined the front in late 1944. The colony also provided many white officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) to other African divisions in Burma. Almost every African battalion in Burma had Rhodesian leaders.

The RAR was formed in May 1940. Most volunteers came from Mashonaland. It started with one battalion and expanded to two in late 1943.

1RAR trained in Kenya and Ceylon. In December 1944, it joined the Burma Campaign at Chittagong. The brigade supported the 25th Indian Division in northwestern Burma. They advanced through the Mayu peninsula and took part in the Battle of Ramree Island.

Japanese troops in Burma believed that African soldiers were cannibals. This was partly due to rumors spread by the black troops themselves. This belief had a strong psychological effect on the Japanese.

In March 1945, the 22nd Brigade, including 1RAR, was tasked with clearing Japanese troops from the Taungup area. 1RAR patrolled the area and had several contacts with the enemy. On April 26, 1RAR led the Battle of Tanlwe Chaung. After bombing and artillery fire, elements of 1RAR charged the hills and defeated the Japanese. Seven RAR men were killed and 22 were wounded.

1RAR spent May 1945 building quarters and training. They then marched to Prome in June. The monsoon season made operations difficult due to mud. From early July, 1RAR patrolled around Gyobingauk, engaging Japanese parties. Even after Japanese commanders surrendered, Allied troops continued patrolling to deal with stragglers. After the formal surrender in September 1945, 1RAR guarded Japanese prisoners in Burma. They returned home in March 1946.

Other Places Southern Rhodesians Served

Southern Rhodesian servicemen also served in other parts of the war. Rhodesian sailors in the Royal, South African, and Merchant Navies crewed ships worldwide. This included the Indian Ocean, the Arctic, and the Pacific. No. 237 (Rhodesia) Squadron operated in Iran and Iraq in 1942–43. They guarded oil wells and supported the British Tenth Army.

Closer to home, Southern Rhodesian military surveyors helped plan the Allied invasion of Madagascar in May 1942. They landed with the invading forces. They stayed on the island long after the French garrison surrendered. The last Rhodesian left Madagascar in October 1943.

Home Front Efforts

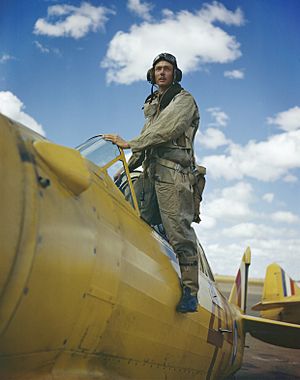

Rhodesian Air Training Group

Southern Rhodesia's role in the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS) is considered its greatest contribution to the Allied victory. The Rhodesian Air Training Group (RATG) eventually ran 11 airfields. This required a huge national effort to build, maintain, and staff them. At its peak, more than a fifth of the white population was involved. This allowed Southern Rhodesia to contribute much more than if it had only sent men to fight.

Southern Rhodesia was ideal for air training. It was far from the fighting, supported Britain, and had excellent weather. The RATG was the last EATS group formed, but the first to start training airmen. It also produced qualified pilots before any other group, starting in November 1940.

The training program was expanded to eight flying schools. There were also two air firing and bombing ranges. Six reserve landing grounds were built to prevent congestion. Later, a special air station trained instructors. Small offices were set up in South Africa to handle equipment and personnel.

The pilot's course initially lasted six months. Trainees learned ground subjects and had to fly at least 150 hours. Later, the course was shortened to speed up pilot output.

Trainees came from all over the world, mostly British. They included people from South Africa, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, America, Yugoslavia, Greece, France, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, Fiji, and Malta. British officials praised Southern Rhodesia's consistent flow of well-trained pilots and observers.

Home Service

The Rhodesian African Rifles (RAR) were based in Salisbury from 1940 to 1943. Their main role was garrison duties within the colony. The Rhodesian Air Askari Corps, a unit of black volunteers, guarded air bases and provided labor.

The war led to more black men and white women taking on higher responsibilities in the British South Africa Police (BSAP). The BSAP hired more black patrolmen as the urban black population grew. This led to more appreciation for black constables.

Women's Contributions

White Southern Rhodesian women served in auxiliary units. The government set up three women's services: the Women's Auxiliary Volunteers (WAV), the Women's Auxiliary Air Service (WAAS), and the Women's Auxiliary Military Service (WAMS). Most servicewomen served within Southern Rhodesia. Some went to East Africa.

These services aimed to replace men with women in military and air forces where possible. Recruitment began in June 1941. Most volunteers were married women. They worked as typists, clerks, caterers, drivers, and in workshops. Many women in the air service did skilled work, like checking flying instruments and doing repairs. Women in the Auxiliary Police Service served as BSAP officers.

White women who did not join the forces also helped. They worked in factories. The Women's National Service League sent parcels to servicemen overseas. These parcels contained clothes, newspapers, soap, food, and small luxuries. This helped keep the troops' morale high.

Economic Impact and Conscripted Labor

The Southern Rhodesian economy grew a lot during the war. War spending increased greatly. Total spending on the air training scheme alone was over £11 million. These amounts were huge for a white population of less than 70,000.

Southern Rhodesia was the world's second-largest gold producer. Gold remained its main income. However, many mines shifted to strategic minerals like chrome and asbestos. Southern Rhodesia became a main source of chrome for the Allies. It was also the world's third-largest producer of asbestos. The government encouraged new industries to use the colony's natural resources.

The RATG created a small economic boom. It also led to the first direct demand for labor from Southern Rhodesia's black population: building airfields. The government assigned labor quotas to districts. Local chiefs and headmen provided workers. This system was called chibaro.

The chibaro workers received pay, but it was low. Many men ran away to avoid the call-up. Some feared they might be drafted to fight overseas.

A severe drought in 1941–42 caused a food shortage. In June 1942, the Compulsory Native Labour Act was passed. This allowed unemployed black men aged 18 to 45 to be conscripted for work on white-owned farms. This conscription helped increase the country's farm output. The scheme continued until 1946.

A Food Production Committee helped white farmers grow more crops. Maize production grew by 40%. Potato and onion harvests also increased. Tobacco production was high. The beef industry also grew. Southern Rhodesia also provided goods like timber, leather, and building materials to the Eastern Group Supply Council.

Internment Camps and Polish Refugees

Thousands of Axis prisoners of war (POWs) and "enemy aliens" were held in Southern Rhodesia. These were mainly Italians and Germans. The colony also hosted nearly 7,000 refugees from Poland. Britain asked Southern Rhodesia to manage investigations into enemy aliens in central Africa.

Five internment camps were set up. No. 1 and No. 2 camps housed Germans. The other three camps housed about 5,000 Italians from Somaliland and Abyssinia. The newer camps had poor living conditions and many escapes.

Polish refugees were housed in special settlements near Marandellas and Rusape from 1943. These camps were run by local authorities and the Polish consulate. The Polish government-in-exile provided money. Many Poles returned to Europe after the war. Southern Rhodesia allowed about 726 Polish refugees to settle permanently.

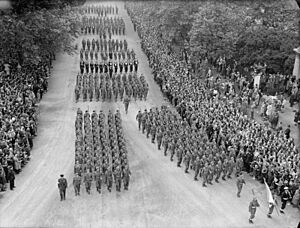

End of the War

Southern Rhodesia sent soldiers, airmen, and seamen to London for the Victory Parade on June 8, 1946. The colony's group marched after South Africa. The Southern Rhodesian color guard included a white officer and two black sergeants. In April 1947, King George VI gave the Rhodesia Regiment the title "Royal" for its service in both World Wars.

War Statistics

Southern Rhodesia contributed more manpower to the Allied cause, compared to its white population, than any other British dominion or colony. A total of 26,121 Southern Rhodesians served. This included 15,153 black men, 9,187 white men, 1,510 white women, and 271 coloured and Indian men. Of those who served overseas, 6,520 were white men and 1,505 were black men.

About 33,145 black Southern Rhodesians were conscripted for labor. The Rhodesian Air Training Group trained 8,235 Allied airmen.

A total of 2,409 Southern Rhodesians served in the RAF. Many others served in the Southern Rhodesian forces or the British or South African Armies. Southern Rhodesians received 698 decorations for bravery. White people received 689, while black troops won nine. No coloured or Indian servicemen were decorated.

Sadly, 916 Southern Rhodesians died from enemy action. This included 498 airmen, 407 ground troops, eight seamen, and three female personnel. Another 483 were wounded.

What Happened After the War

The Rhodesian Air Training Group was very important for Southern Rhodesia's history. It led to great economic growth. Many former instructors and trainees moved to the colony after the war. This caused Southern Rhodesia's white population to more than double by 1951. RAF training operations in the country ended in March 1954.

Ties with South Africa grew stronger after the war. Both countries became more industrialized. The economy of Southern Rhodesia grew rapidly after 1945. Huggins remained Prime Minister for another decade. He oversaw the Federation with Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1953.

Southern Rhodesia also helped in other Commonwealth operations in the 1950s and early 1960s. This included the Malayan Emergency.

The Federation ended in 1963. Two years later, Southern Rhodesia's mostly white government declared independence (UDI). Many World War II veterans, including Prime Minister Ian Smith, were in this government. They declared independence on Armistice Day, November 11, at 11:00 AM. The UK government banned Rhodesia from the annual Armistice Day service in London. Smith's government held its own ceremony. World War II veterans held many important positions in the Rhodesian Security Forces during the Bush War in the 1970s.

After Zimbabwe became independent in 1980, the government removed many war memorials. They saw them as reminders of white minority rule and colonialism. Many Zimbabweans believe their nation's involvement in the World Wars was mainly a result of colonial rule. Southern Rhodesia's war dead are now remembered in graves in Zimbabwe, South Africa, Zambia, and Greece. They are also remembered at war memorials in the UK.

Images for kids