Italian campaign (World War II) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Italian campaign |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mediterranean and Middle East theatre of World War II and European theatre of World War II | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Allies: • • • Co-belligerents: Supported by: |

Axis: • • |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| May 1944: 619,947 men (ration strength) April 1945: 616,642 men (ration strength) 1,333,856 men (overall strength) Aircraft: 3,127 aircraft (September 1943) 4,000 aircraft (March 1945) |

May 1944: (ration strength) April 1945: (ration strength) (overall strength) (military only) Aircraft: (September 1943) (April 1945) |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Sicily: Vehicles: 8,011 aircraft destroyed |

Sicily: Aircraft: |

||||||||

| 152,940 civilians killed | |||||||||

The Italian campaign was a major part of World War II. It involved battles between the Allied powers and the Axis powers in and around Italy. This campaign lasted from 1943 to 1945. After the German occupation in September 1943, it was also known as the Liberation of Italy.

The Allied Forces Headquarters (AFHQ) was in charge of all Allied ground forces in the Mediterranean area. They planned and led the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. This was followed by the invasion of mainland Italy in September. The campaign continued until the German forces in Italy surrendered in May 1945.

Many lives were lost during this campaign. Between September 1943 and April 1945, about 60,000 to 70,000 Allied soldiers died. Around 38,805 to 50,660 German soldiers also lost their lives. The total number of Allied soldiers who were injured or killed was about 330,000. For the Germans, this number was over 330,000. Before its collapse, Fascist Italy had about 200,000 casualties. Most of these were prisoners taken during the invasion of Sicily. Over 150,000 Italian civilians died. Also, 35,828 anti-fascist fighters and about 35,000 troops from the Italian Social Republic were killed.

The invasion of Sicily in July 1943 led to big changes in Italy. The Fascist government, led by Benito Mussolini, collapsed. King Victor Emmanuel III ordered Mussolini's arrest on July 25. The new Italian government then signed an agreement with the Allies on September 8, 1943.

However, German forces quickly took control of northern and central Italy. German paratroopers rescued Mussolini. He then set up a new government called the Italian Social Republic (RSI). This was a puppet state that worked with the Germans. German soldiers, sometimes with Italian fascists, also committed terrible acts against civilians.

During this time, the Italian Co-Belligerent Army was formed. They fought alongside the Allies against the RSI and its German allies. There was also a large Italian resistance movement fighting the Germans. Other Italian troops continued to fight with the Germans. This period is known as the Italian Civil War. In April 1945, Italian resistance fighters captured Mussolini. He was then executed. The campaign ended when the German Army Group C surrendered on May 2, 1945. This was one week before Germany's official surrender. Even small independent states like San Marino and the Vatican, which are surrounded by Italy, were affected by the fighting.

Contents

Why Italy? Understanding the Strategy

Before the Allies won the North African campaign in May 1943, they disagreed on how to defeat the Axis powers. The British, especially Prime Minister Winston Churchill, preferred a strategy that used their strong navy. They wanted to blockade the enemy and launch smaller attacks around the edges of Europe.

The United States, with its larger army, wanted a more direct approach. They aimed to fight the main German forces in northwestern Europe. This big attack, however, depended on first winning the Battle of the Atlantic.

The disagreement was strong. American leaders wanted to invade France as soon as possible. They felt no other operations should delay this main effort. The British argued that they already had many troops ready for sea landings in the Mediterranean. This made a smaller invasion possible and useful.

Eventually, the leaders of the U.S. and Britain found a middle ground. They agreed to focus most of their forces on invading France in early 1944. But they would also launch a smaller campaign in Italy. President Franklin D. Roosevelt wanted to keep U.S. troops active in Europe in 1943. He also liked the idea of getting Italy out of the war.

They hoped an invasion would force Italy to surrender. This would allow Allied navies, especially the British Royal Navy, to control the Mediterranean Sea. This would make it safer to send supplies to Egypt and Asia. Also, Italian soldiers guarding areas in the Balkans and France would have to return to defend Italy. The Germans would also need to move troops from the Eastern Front to defend Italy. This would help the Soviet Union.

The Campaign Begins: Sicily and Mainland Italy

Invading Sicily: Operation Husky

The Allied invasion of Sicily was called Operation Husky. It started on July 9, 1943. Soldiers landed from the sea and dropped from the sky near the Gulf of Gela. The main forces involved were the U.S. Seventh Army led by George S. Patton. Also, the 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade, led by Guy Simonds, were there. The British Eighth Army, led by Bernard Montgomery, also took part.

The original plan was for the British to push north along the east coast to Messina. The Canadians would be in the middle, and the Americans on the left. The Americans had the important job of pushing Axis forces out of Sicily on their left side. When the British Eighth Army faced strong defenses near Mount Etna, General Patton expanded the American role. They advanced northwest towards Palermo and then north to cut off the coastal road.

This was followed by an advance east of Etna towards Messina. Small sea landings on the northern coast helped Patton's troops reach Messina. They arrived just before the first units of the Eighth Army. The German and Italian defenders could not stop the Allies from taking the island. However, they managed to move most of their troops to the mainland. The last ones left on August 17, 1943. The Allied forces gained valuable experience in these difficult operations.

Landing on Mainland Italy

On September 3, 1943, British Eighth Army forces landed in the 'toe' of Italy. This was called Operation Baytown. It happened on the same day the Italian government agreed to an armistice with the Allies. The armistice was announced publicly on September 8.

On September 9, the U.S. Fifth Army, led by Mark W. Clark, landed at Salerno. This was Operation Avalanche. They expected little resistance but met strong German defenses. British forces also landed at Taranto in Operation Slapstick, facing almost no opposition.

The Allies hoped the Germans would retreat north after Italy surrendered. At first, Adolf Hitler thought Southern Italy was not important. But this did not happen. The Eighth Army made good progress up the eastern coast. They captured the port of Bari and important airfields near Foggia. Even without extra troops, the German 10th Army almost pushed back the Salerno landing.

The main Allied goal in the west was the port of Naples. This city was chosen because it was the northernmost port that fighter planes from Sicily could protect. In Naples itself, anti-Fascist groups started an uprising. This was known as the Four Days of Naples. They fought bravely until Allied forces arrived.

As the Allies moved forward, they faced very difficult land. The Apennine Mountains run like a spine down the Italian peninsula. In the most mountainous areas, over half the land has peaks over 900 meters high. These areas were easy to defend. The Allies had to cross many ridges and rivers. The rivers could flood suddenly, which made Allied plans difficult.

Pushing North: The Advance on Rome

In early October 1943, Hitler was convinced by his commander in Southern Italy, Albert Kesselring, to defend Italy far from Germany. This would use Italy's natural defenses in the center of the country. It would also stop the Allies from easily capturing airfields closer to Germany. Hitler also believed that giving up southern Italy would allow the Allies to invade the Balkans. This region had important oil, bauxite, and copper resources.

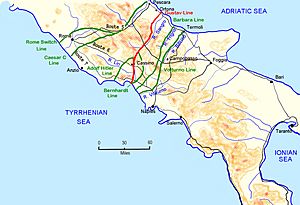

Kesselring took command of all forces in Italy. He immediately ordered the building of several defensive lines south of Rome. Two lines, the Volturno and the Barbara, were used to slow down the Allied advance. This bought time to prepare the strongest defenses, known as the Winter Line. This included the Gustav Line and two other lines in the west, the Bernhardt and Hitler lines.

The Winter Line was a huge challenge for the Allies in late 1943. It stopped the Fifth Army's advance on the western side of Italy. The Eighth Army broke through the Gustav Line on the Adriatic coast. Ortona was captured, but with heavy losses for Canadian troops. However, blizzards and deep snow in December stopped the advance completely.

The Allies then focused on the western front. An attack through the Liri valley seemed to offer the best chance to reach the Italian capital. Landings behind the line at Anzio were planned. This was called Operation Shingle. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill supported it. The goal was to weaken the German Gustav Line defenses.

However, the early push inland to cut off German defenses did not happen. The American commander, John P. Lucas, disagreed with the plan. He felt his forces were not large enough. Lucas dug in his troops, which gave Kesselring time to gather enough forces. The Germans then surrounded the beachhead. After a month of hard fighting, Lucas was replaced by Lucian Truscott. Truscott eventually broke out in May.

It took four major attacks between January and May 1944 to finally break the line. A combined assault by the Fifth and Eighth Armies achieved this. Forces from Britain, America, France, Poland, and Canada were involved. They focused their attack along a 32-kilometer front between Monte Cassino and the western coast.

At the same time, General Mark W. Clark was ordered to break out of the Anzio position. He was supposed to cut off and destroy a large part of the German 10th Army. This army was retreating from the Gustav Line. But Clark missed this chance. He disobeyed orders and sent his U.S. forces to enter Rome instead. Rome had been declared an open city by the German Army, so there was no resistance.

American forces took Rome on June 4, 1944. The German 10th Army was able to escape. This may have caused twice as many Allied casualties in the following months. Clark was seen as a hero in the United States. However, later reviews of his decisions have been critical.

Final Push: Into Northern Italy

After Rome was captured, and the Allied invasion of Normandy happened in June, some Allied units left Italy. The U.S. VI Corps and the French Expeditionary Corps (CEF) were moved. These seven divisions went to take part in Operation Dragoon, the invasion of Southern France.

The sudden removal of these experienced troops was partly made up for. Three new divisions arrived gradually. These were the Brazilian 1st Infantry Division, the U.S. 92nd Infantry Division, and the U.S. 10th Mountain Division.

From June to August 1944, the Allies moved past Rome. They captured Florence and got close to the Gothic Line. This was the last major German defensive line. It stretched from the coast north of Pisa, across the Apennine Mountains between Florence and Bologna, to the Adriatic coast near Rimini. To shorten their supply lines, the Polish II Corps advanced towards the port of Ancona. After a month-long battle, they captured it on July 18.

During Operation Olive, which began on August 25, the Allies broke through the Gothic Line. This happened on both the Fifth and Eighth Army fronts. But there was no decisive breakthrough. British Prime Minister Churchill hoped a big advance in late 1944 would open a path. He wanted Allied armies to move northeast through the "Ljubljana Gap" (now Slovenia). This would lead to Vienna and Hungary. He hoped to stop the Red Army from advancing into Eastern Europe. However, U.S. military leaders strongly opposed this. They felt it did not fit the overall Allied war priorities.

In October, Richard McCreery took over as commander of the Eighth Army. In December, Mark Clark, the Fifth Army commander, was given command of the 15th Army Group. This meant he was in charge of all Allied ground troops in Italy. Harold Alexander then became the Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean. Lucian K. Truscott Jr. replaced Clark as commander of the Fifth Army.

During the winter and spring of 1944–45, partisan groups were very active in Northern Italy. Since there were two Italian governments at this time (one on each side of the war), the fighting also became a civil war.

Bad winter weather made it impossible to move tanks and use air power. The Allies also suffered huge losses in the autumn fighting. Some British troops had to be sent to Greece. Also, some British and Canadian units were moved to northwestern Europe. Because of this, the Allies could not continue their attack in early 1945. Instead, they focused on defending while preparing for a final attack in the spring.

In late February and early March 1945, Operation Encore took place. Parts of the U.S. IV Corps (including the 1st Brazilian Division and the U.S. 10th Mountain Division) fought through minefields in the Apennines. They pushed German defenders from key high points like Monte Castello, Monte Belvedere, and Castelnuovo. This removed German artillery positions that had been blocking the way to Bologna. Meanwhile, damage to roads forced Axis forces to use sea, canal, and river routes for supplies. This led to Operation Bowler against ships in Venice harbor on March 21, 1945.

The Allies' final attack began with massive air and artillery bombardments on April 9, 1945. By April 1945, the Allies had 1,500,000 men and women in Italy. The Axis had 599,404 troops on April 7. Of these, 439,224 were Germans and 160,180 were Italians. By April 18, Eighth Army forces in the east broke through the Argenta Gap. They sent tanks forward to meet the U.S. IV Corps. This trapped the remaining defenders of Bologna. On April 21, Bologna was entered by the 3rd Carpathian Division, the Italian Friuli Group (both from the Eighth Army), and the U.S. 34th Infantry Division (from the Fifth Army).

The U.S. 10th Mountain Division bypassed Bologna and reached the River Po on April 22. The 8th Indian Infantry Division, from the Eighth Army, reached the river on April 23.

By April 25, Italian partisan groups declared a general uprising. On the same day, after crossing the Po River, Eighth Army forces moved north-northeast towards Venice and Trieste. On the U.S. Fifth Army front, divisions pushed north toward Austria and northwest to Milan. On the Fifth Army's left, the U.S. 92nd Infantry Division (the "Buffalo Soldiers Division") moved along the coast to Genoa. A quick advance towards Turin by the Brazilian division surprised the German–Italian Army of Liguria, causing it to collapse.

Between April 26 and May 1, the Battles of Collecchio-Fornovo di Taro took place. The 148th German Infantry Division surrendered to Brazilian soldiers. The Brazilian soldiers captured about 15,000 Italian and Nazi soldiers. These battles marked the end of fighting in Italy and the end of the Italian fascist army.

As April 1945 ended, the German Army Group C was retreating on all fronts. It had lost most of its fighting strength and had little choice but to surrender. General Heinrich von Vietinghoff signed the surrender document for the German armies in Italy on April 29. This officially ended the fighting on May 2, 1945.

Images for kids

See also

- Italian front (World War I)

- Liberation of France

- Military history of Italy during World War II

- Italian Co-Belligerent Army

- Italian Co-Belligerent Navy

- Italian Co-Belligerent Air Force

- Italian Social Republic

- Italian resistance movement

- Italian Civil War

- List of British military equipment of World War II

- List of equipment of the United States Army during World War II

- List of German military equipment of World War II

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |