Albert Kesselring facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Albert Kesselring

|

|

|---|---|

Kesselring wearing his Knight's Cross in 1940

|

|

| Nickname(s) | Smiling Albert Uncle Albert |

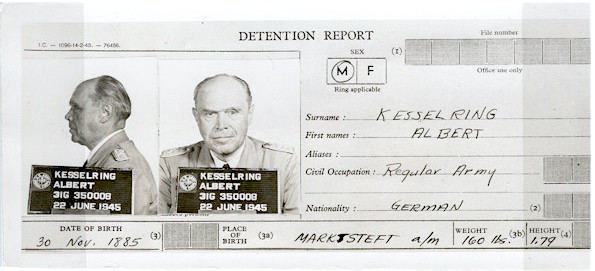

| Born | 30 November 1885 Marktsteft, Kingdom of Bavaria, German Empire |

| Died | 16 July 1960 (aged 74) Bad Nauheim, Hessen, West Germany |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1904–1945 |

| Rank | Generalfeldmarschall |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | World War I

World War II

|

| Awards | Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds |

| War crimes | |

| Conviction(s) | War crimes |

| Criminal penalty | Death; commuted to life imprisonment; further commuted 21 years' imprisonment |

Albert Kesselring (born November 30, 1885 – died July 16, 1960) was a German military officer. He served in the German Air Force (called the Luftwaffe) during World War II. Kesselring was a highly decorated commander. He received the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds, one of the highest military awards.

Kesselring joined the Bavarian Army in 1904 as a young officer. He served in the artillery. Before World War I, he trained to observe from balloons. During World War I, he fought on both the Western and Eastern fronts. After the war, he continued to serve in the German army. In 1933, he helped rebuild Germany's air force, which had been banned after World War I. He became the Luftwaffe's chief of staff from 1936 to 1938.

During World War II, Kesselring led Luftwaffe forces in the invasions of Poland and France. He also played a role in the Battle of Britain and the invasion of the Soviet Union (called Operation Barbarossa). He was the main German commander in the Mediterranean area, which included the North African campaign. Kesselring led a strong defense against Allied forces in Italy. He was injured in an accident in October 1944. Towards the end of the war, he commanded German forces on the Western Front.

After the war, Kesselring was found guilty of serious actions during the conflict. He was sentenced to death for ordering the killing of 335 Italian civilians in the Ardeatine massacre. He was also found guilty of encouraging his troops to harm civilians as a way to punish the Italian resistance movement. His death sentence was later changed to life in prison. He was released in 1952 due to health reasons. Kesselring wrote his memoirs, Soldat bis zum letzten Tag ("A Soldier to the Last Day"), in 1953. He passed away in 1960.

Contents

- Early Life and Military Beginnings

- World War I Experiences

- Between the World Wars

- World War II Campaigns

- After the War

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Military Beginnings

Albert Kesselring was born in Marktsteft, Bavaria, on November 30, 1885. His father, Carl Adolf Kesselring, was a schoolmaster.

In 1904, after finishing school, Kesselring joined the German Army. He became an officer cadet in an artillery regiment. He stayed with this regiment until 1915, except for periods at military schools. In 1906, he became a Leutnant (lieutenant).

In 1910, Kesselring married Luise Anna Pauline (Liny) Keyssler. They did not have children of their own, but in 1913, they adopted Rainer, his second cousin's son. In 1912, Kesselring trained as a balloon observer. This showed his early interest in aviation. His leaders thought he was very good at combining military plans with new technology.

World War I Experiences

During World War I, Kesselring served with his regiment in Lorraine. In 1914, he moved to the 1st Bavarian Foot Artillery. He was promoted to captain in May 1916. He showed great skill in the Battle of Arras in 1917. He worked tirelessly to stop the British advance. For his service on the Western Front, he received the Iron Cross, 1st Class.

In 1917, he joined the General Staff, even though he had not attended the special War Academy. He also served on the Eastern Front. His experiences there helped shape his strong views against communism. In January 1918, he returned to the Western Front as a staff officer.

Between the World Wars

Joining the Reichswehr

After World War I, Kesselring helped with the demobilization of German troops. In 1919, he became a battery commander. He joined the Reichswehr (Germany's new army) in October 1922. He worked at the Ministry of the Reichswehr in Berlin. He helped organize the army and develop new weapons.

In 1929, he returned to Bavaria as a commander. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1930. He spent two years in Dresden with the 4th Artillery Regiment.

Building the Luftwaffe

In 1933, Kesselring left the Reichswehr. He was appointed head of administration for aviation. At this time, Germany was not allowed to have an air force. This was a secret way to rebuild it. The Luftwaffe (German Air Force) was officially created in February 1935. Kesselring helped build new factories and worked with engineers.

He was quickly promoted in the Luftwaffe. He became a Generalmajor in 1934 and a Generalleutnant in 1936. He also received special monthly payments from Adolf Hitler.

At 48, Kesselring learned to fly planes himself. He believed officers should understand what their soldiers do. He flew several types of aircraft regularly until March 1945.

Kesselring became Chief of Staff of the Luftwaffe in June 1936. He oversaw its growth and the development of new aircraft like the Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter and Junkers Ju 87 dive-bomber. He also helped develop paratroopers.

He supported the Condor Legion in the Spanish Civil War. He had disagreements with his superior, General der Flieger Erhard Milch. Kesselring asked to be transferred to a field command. He was given command of Luftgau III (Air District III) in Dresden. He was promoted to General der Flieger in 1937 and became commander of Luftflotte 1 in 1938.

Air Force Strategy

Kesselring believed air power was important for supporting ground operations. He focused on using planes to help the army. He also supported building long-range heavy bombers. As chief of staff, he pushed for new technologies and training for bombing missions. He was promoted to Generalfeldmarschall in 1940.

World War II Campaigns

Poland Invasion

In the Polish campaign of 1939, Kesselring's Luftflotte 1 supported Army Group North. He had 1,105 aircraft. His main goal was to attack Polish airfields. Once air superiority was achieved, the Luftwaffe focused on supporting ground troops.

The Luftwaffe found it hard to locate all Polish airfields. Only 24 Polish aircraft were destroyed on the ground. However, air superiority was achieved by disrupting Polish communications. Kesselring himself was shot down during this campaign.

His air fleet helped destroy two Polish armies in the Battle of the Bzura. Kesselring also ordered air attacks against Warsaw in late September. About 10 percent of the city's buildings were destroyed. Between 20,000 and 25,000 civilians were killed. Kesselring said only military targets were attacked, but the bombing was not precise. For his role, Hitler awarded him the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.

France and Low Countries

Kesselring's Luftflotte 1 was not initially involved in the campaigns in the west. However, after a German invasion plan was accidentally revealed, Kesselring was given command of Luftflotte 2 in January 1940. This air fleet supported Army Group B.

Kesselring's air operations were successful against the small Belgian and Dutch air forces. However, the German paratroopers suffered heavy losses in the Battle for The Hague and the Battle of Rotterdam. On May 14, 1940, Kesselring ordered the bombing of Rotterdam city center. Fires destroyed much of the city, killing about 800 civilians.

After the Netherlands surrendered, Luftflotte 2 moved to Belgium. The Battle of France was going well. By May 24, Allied forces were cut off near Dunkirk. German leaders wanted to destroy the Allied forces from the air. Kesselring and his commanders were not confident due to heavy losses and long distances. The German air operation failed to stop the evacuation.

Kesselring's air fleet then focused on the final phase of the battle for France. They conducted a strategic air offensive against Paris. The campaign was quick, and the Luftwaffe gained air superiority. For his part in the western campaign, Kesselring was promoted to Generalfeldmarschall (field marshal).

Battle of Britain

After France, Kesselring's Luftflotte 2 was sent to the Battle of Britain. His headquarters was in Brussels. Kesselring's air fleet was the largest in the Luftwaffe. He was responsible for bombing southeastern England and London. Later, Luftflotte 3 took over night attacks, while Luftflotte 2 handled daylight operations.

Kesselring was unsure about attacking Britain. He preferred capturing Gibraltar first. However, the German air force leader, Hermann Göring, believed the British air force was weak. Kesselring agreed with Göring, thinking the British fighter command could be easily defeated.

The first phase of the battle was only partly successful. German attacks on British airfields peaked in early September 1940. Göring decided to attack London to draw out the remaining British fighters. Kesselring enthusiastically supported this idea. However, British intelligence showed their fighter command was not near collapse.

The focus shifted to destroying docks and factories in London. This decision relieved pressure on the British fighter command. On September 7, Kesselring's air fleet was still the largest. Eight days later, his fleet carried out a major daylight attack on London. This attack is seen as the climax of the battle. The German airmen faced a prepared enemy and suffered heavy losses.

Luftflotte 2 continued the Blitz on British cities until May 1941. They bombed cities like Birmingham and Coventry. The aim was to disrupt production and make workers homeless.

Invasion of the Soviet Union

Luftflotte 2 was moved to the east for operations against the Soviet Union. This move was kept secret from the British. Kesselring made sure his air fleet had extra transport to keep up with fast-moving ground troops. However, German logistics struggled, and many vehicles became unusable.

Luftflotte 2 supported Army Group Centre. Kesselring's goal was to gain air superiority quickly while supporting ground operations. He had 1,223 aircraft, half of the Luftwaffe's total. Kesselring said he told his air force generals to treat the army's requests as orders.

The German attack surprised the Soviet Air Force. Kesselring reported that in the first week, Luftflotte 2 destroyed 2,500 Soviet aircraft. With air superiority, Luftflotte 2 focused on ground operations. They protected the sides of the armored advances. Kesselring worked to improve cooperation between the army and air force.

By July 26, Kesselring reported destroying many enemy vehicles and aircraft. His air fleet supported battles like Białystok–Minsk and Smolensk. Minsk was heavily damaged by German air raids. However, the air fleet suffered heavy losses.

In late 1941, Luftflotte 2 supported the final German attack on Moscow, Operation Typhoon. Raids on Moscow were dangerous due to strong Soviet defenses. Kesselring was pessimistic about the results of these raids.

The air fleet provided effective support in the early stages of the offensive. However, bad weather hindered operations. Kesselring's air fleet was moved to the Mediterranean in November. This weakened German air power in the Soviet Union. The air superiority Germany had earlier in the war faded.

Mediterranean and North Africa

In November 1941, Kesselring became the German Commander-in-Chief South. He moved to Italy with his Luftflotte 2 staff. He commanded ground, naval, and air forces.

Controlling Malta was very important. Malta was a British base that allowed attacks on Axis supply ships heading to North Africa. Kesselring ordered attacks on Malta's airfields and ports. He also attacked Malta Convoys, which supplied the island.

Kesselring's Luftflotte 2 had an immediate impact. The offensive began on March 20, 1942. They flew 11,000 sorties against Malta. This caused severe hardship for the island's population. Axis shipping losses decreased significantly.

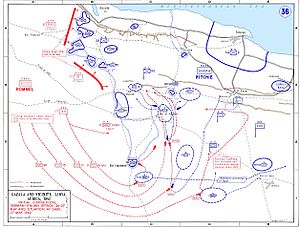

By suppressing Maltese forces, Kesselring helped deliver more supplies to Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps in Libya. Rommel then prepared an attack on British positions. Kesselring planned Operation Herkules, an airborne and sea attack on Malta. He hoped to secure the supply lines to North Africa.

For the Battle of Gazala, Kesselring temporarily took command of some ground units. He helped solve Rommel's supply problems. Kesselring was critical of Rommel's performance in the Battle of Bir Hakeim. After heavy air strikes, Bir Hakeim was evacuated by the French. For his role, Kesselring received the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords.

After capturing Tobruk, Rommel convinced Hitler to attack Egypt instead of Malta. Kesselring and the Italians disagreed. The Malta operation was never fully supported by German high command. The failure to take Malta was a major setback for the Axis in North Africa.

Logistical problems grew, leading to the disastrous First Battle of El Alamein and Battle of Alam el Halfa. Kesselring supported Rommel's decision to withdraw. Kesselring believed Rommel was a great general for fast-moving troops, but too unpredictable for higher command.

In October 1942, Kesselring was given direct command of all German armed forces in the theater, except Rommel's army. His command also included troops in Greece and the Balkans.

Tunisia Campaign

Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of French North Africa, created a crisis for Kesselring. He quickly sent troops to Tunisia to establish a defensive position. By December, the Allied commander, Dwight D. Eisenhower, admitted that Kesselring had won the race to secure Tunisia.

Kesselring hoped to launch an offensive to drive the Allies out of North Africa. At the Battle of the Kasserine Pass, his forces inflicted heavy losses on the Allies. However, strong Allied resistance stopped the advance. Kesselring focused on moving supplies from Italy, but Allied aircraft and submarines hindered his efforts. An Allied offensive in April finally broke through. About 275,000 German and Italian troops were captured. Kesselring had delayed the Allies in Tunisia for six months. This delay contributed to the postponement of an Allied invasion of Northern France until 1944.

Kesselring was nicknamed "Smiling Albert" by the Allies. His own troops called him "Uncle Albert." He was popular because he often visited the front lines.

Italian Campaign Defense

Sicily Landing

Kesselring expected the Allies to invade Sicily next. He reinforced the island with German divisions. He knew this force could not stop a large invasion. He hoped for an immediate counterattack.

The Allied invasion of Sicily on July 10, 1943, met strong resistance. Allied air forces forced Luftflotte 2 to withdraw most of its aircraft to the mainland. Kesselring flew to Sicily on July 12 to assess the situation. He decided that only a delaying action was possible. He reinforced Sicily with more divisions.

Kesselring managed to delay the Allies in Sicily for another month. The Allied conquest of Sicily was complete by August 17. His evacuation of Sicily was very successful. He evacuated 40,000 men, vehicles, and supplies. He achieved excellent coordination among his forces.

Allied Invasion of Italy

After Sicily fell, German high command feared Italy would leave the war. Kesselring remained confident the Italians would fight. Hitler decided to hold the Po Valley in northern Italy. Kesselring was ordered to withdraw from southern Italy. He was to join Rommel's forces in the north. Kesselring was to be transferred to Norway.

Kesselring believed Italy could be held for six to nine months. He thought the Allies would not operate beyond their air cover. He resigned on August 14, 1943, but Hitler refused to accept it. Hitler believed Kesselring was too optimistic but militarily capable.

Italy withdrew from the war on September 8. The Germans disarmed Italian units. Kesselring immediately moved to secure Rome. He used a mix of bluff and force to overcome Italian resistance. He secured the city in two days.

Benito Mussolini was rescued by the Germans in Unternehmen Eiche on September 12. Italy became an occupied country. Kesselring blamed the Allies for the tragedy in Italy. He felt Hitler would have let Italy leave the war if the Allies had respected its neutrality.

Salerno and Defensive Lines

Kesselring intended to fight hard. At the Battle of Salerno in September 1943, Kesselring launched a counterattack against the US Fifth Army. The attack caused heavy casualties for the Allies. It forced them back in some areas. Luftflotte 2 launched 120 aircraft over Salerno. The German offensive failed due to Allied naval gunfire and strong resistance. Kesselring gained precious time.

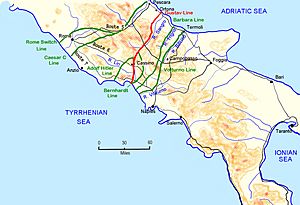

He prepared a series of defensive positions: the Volturno Line, the Barbara Line, and the Bernhardt Line. The Apennine Mountains in Italy favored defense. The Germans used a "reverse slope defense," hiding their positions. Bad weather also helped the defenders.

In November 1943, the Allies reached Kesselring's main position, the Gustav Line. This was the narrowest part of the peninsula. Kesselring believed it could be held with fewer divisions. He met with Hitler in November 1943. Kesselring gave an optimistic assessment. Hitler then moved Rommel to France. On November 21, 1943, Kesselring took command of all German forces in Italy.

The Luftwaffe had a notable success on December 2, 1943. 105 Junkers Ju 88s attacked the port of Bari. They used chaff to confuse Allied radar. The port was full of brightly lit Allied ships. This was a very destructive air raid. Some 16 ships were sunk. The port was out of action for three weeks.

Cassino and Anzio Battles

The first Allied attempt to break the Gustav Line in the Battle of Monte Cassino in January 1944 had some early success. Kesselring quickly sent reserves to the front. They stabilized the German position.

Kesselring felt surprised when the Allies landed at Anzio. He quickly moved forces to counter the landing. He brought in divisions from northern Italy and the Cassino front. He also received troops from other theaters. By February, Kesselring was able to launch an offensive at Anzio. His forces could not crush the Allied beachhead.

Meanwhile, fierce fighting continued at Monte Cassino. Kesselring brought in the 1st Parachute Division. Despite heavy losses, an Allied offensive in March 1944 failed to break the Gustav Line.

The Allies launched Operation Strangle, an air campaign to cut German supply lines. This left the German Army Group C very short of fuel and ammunition.

On May 11, 1944, General Sir Harold Alexander launched Operation Diadem. This finally broke through the Gustav Line. The German Tenth Army had to withdraw. Due to fuel shortages, units moved slowly. A gap opened between the Tenth and Fourteenth Armies. Kesselring replaced his army commander.

Fortunately for the Germans, Mark W. Clark, commander of the U.S. Fifth Army, focused on capturing Rome. Kesselring diverted troops to oppose Clark's attack. The Tenth Army was able to link up with the Fourteenth Army. They conducted a fighting withdrawal to the next defense line. For his role, Kesselring received the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds.

Protecting Italian Heritage

Kesselring tried to avoid destroying important Italian cities. These included Rome, Florence, Siena, and Orvieto. Some historic bridges, like the Ponte Vecchio, were booby-trapped instead of being blown up. However, other historic Florentine bridges were destroyed on his orders.

Kesselring supported Rome being declared an open city in August 1943. This meant it should not be attacked. The Allies never fully accepted this, as Rome remained a center of government. Rome was bombed many times by the Allies.

Kesselring believed the open city status helped calm unrest in Rome. He withdrew from Rome without defending it, saving the city from destruction. After the Allies occupied Rome, they used it for military purposes.

Kesselring tried to protect the Monte Cassino monastery. He avoided using it for military purposes. However, the Allies believed it was being used to direct German artillery. On February 15, 1944, Allied bombers destroyed the monastery. Kesselring had some German soldiers shot for looting artworks. A 1945 Allied investigation found that Italian cultural treasures suffered little damage overall. Kesselring's personal interest helped save many art treasures.

Central Europe Operations

After recovering from a car accident, Kesselring was called by Hitler to command the Commander-in-Chief West on March 10, 1945. This was after the loss of the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen. Kesselring remained optimistic despite the desperate situation. He believed Germany would defeat the Soviets and then turn west.

The Western Front generally followed the Rhine River. Kesselring was ordered to hold the Saar–Palatinate triangle. German commanders warned that defending it would lead to heavy losses. Kesselring insisted the positions be held.

The German position quickly crumbled. Kesselring later said Hitler reluctantly allowed a withdrawal. The German First and Seventh Armies suffered heavy losses. However, they avoided being surrounded. They conducted a skillful delaying action. They evacuated their last troops across the Rhine on March 25, 1945.

As Germany was cut in two, Kesselring's command grew. He commanded several Army Groups on the Eastern Front and in Italy. On April 30, Hitler died. The next day, Karl Dönitz became the new German President. Dönitz appointed Kesselring as Commander-in-Chief Southern Germany.

Surrender and Capture

In Italy, German officers had been secretly negotiating a surrender with the Allies. Kesselring knew about these talks. He later informed Hitler. At the last minute, Kesselring changed his mind about accepting the surrender. He feared it would endanger his other forces. On April 30, he relieved his commanders who were pushing for surrender.

The next morning, May 1, these commanders were arrested. However, they soon regained control. They agreed to a quick surrender. The German armies in Italy were defeated. Kesselring remained opposed to the surrender. He was finally convinced by Karl Wolff on May 2. The armistice became effective at 2:00 PM on May 2.

North of the Alps, Army Group G surrendered on May 6. Kesselring decided to surrender his own headquarters. He surrendered to an American major in Saalfelden, Austria, on May 9, 1945. He was treated courteously by Maxwell D. Taylor, commander of the US 101st Airborne Division. Kesselring was allowed to keep his weapons and field marshal's baton. He was later arrested and held in American and then British custody.

After the War

Trial and Conviction

For many Italians, Kesselring's name became linked with the harsh German occupation. His name was at the top of a list of German officers blamed for many terrible actions.

The Moscow Declaration of October 1943 stated that German officers responsible for atrocities would be sent back to the countries where the deeds happened. The British decided to hold trials in Italy. Kesselring's trial began in Venice on February 17, 1947. The British military court was led by Major General Sir Edmund Hakewill-Smith.

Kesselring was charged with two things: the shooting of 335 Italians in the Ardeatine massacre, and encouraging his troops to kill Italian civilians. Kesselring argued that the order to kill ten Italian civilians for each German soldier killed by resistance fighters was "just and lawful." On May 6, 1947, the court found him guilty of both charges. He was sentenced to death by firing squad.

The British government later decided that no more death sentences should be carried out. They also decided that existing death sentences should be changed. On July 4, 1947, Kesselring's death sentence was changed to life imprisonment.

Release from Prison

In May 1947, Kesselring was moved to Wolfsberg, Carinthia prison. He was later transferred to Werl Prison in Westphalia. While in prison, he worked on a history of the war for the US Army Historical Division. He also secretly worked on his memoirs.

A group in Britain lobbied for his release. This group included Winston Churchill, the former Prime Minister. Churchill called Kesselring a "good general." Field Marshal Alexander, Kesselring's opponent in Italy, also supported his release. Alexander said, "Kesselring and his soldiers fought against us hard but clean."

The Italian government refused to carry out death sentences. The death penalty had been abolished in Italy. This disappointed the British government.

In Germany, the release of military prisoners became a political issue. With the creation of West Germany in 1949, there were calls for amnesty. The German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer made it clear that West Germany's participation in a European defense treaty depended on the release of German military figures.

In July 1952, Kesselring was diagnosed with cancer in his throat. The British were concerned he might die in prison. Kesselring was transferred to a hospital. In October 1952, he was released from prison due to ill health. His release caused protests in Italy.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1952, Kesselring became the honorary president of three veterans' organizations. One was the Luftwaffenring, for Luftwaffe veterans. Another was the Verband deutsches Afrikakorps, for veterans of the Afrika Korps. The third, and most controversial, was the right-wing Der Stahlhelm. He tried to reform this organization.

Kesselring's release caused anger in the Italian Parliament. Kesselring said he had saved the lives of millions of Italians. He said they should build him a monument. In response, an Italian jurist named Piero Calamandrei wrote a poem. The poem said that if Kesselring returned, he would find a monument made of Italian resistance fighters. This poem is on monuments in several Italian towns.

Kesselring's memoirs, Soldat bis zum letzten Tag (A Soldier to the Last Day), were published in 1953. The English edition was called A Soldier's Record. The book sold well. Critics noted that Kesselring did not question where blind obedience ended.

Kesselring died in Bad Nauheim, West Germany, on July 16, 1960, at age 74. He had a heart attack. He was given a funeral by the Stahlhelm veterans' group. His former chief of staff praised him as a man of strong character. The head of the Luftwaffe hoped Kesselring would be remembered for his earlier achievements.

In 2000, a memorial event was held for Kesselring. No representatives from the German military attended. They said Kesselring was "not worthy of being part of our tradition." However, two veterans' groups honored him. To his aging troops, Kesselring remained a respected commander.

Field Marshal's Baton

Kesselring's field marshal's baton was found by an American soldier in July 1945. It remained with the soldier's family until 2010. It was then sold at auction for $731,600.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Albert Kesselring para niños

In Spanish: Albert Kesselring para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |