Spokane Garry facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Spokane Garry

|

|

|---|---|

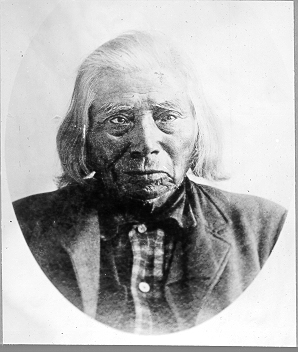

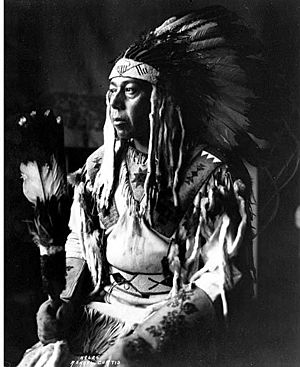

Chief Spokane Garry

|

|

| Born | 1811 Junction of the Spokane and the Little Spokane Rivers

|

| Died | 1892 (aged 80–81) |

| Other names | Chief Garry Spokan Garry Chief Spokane Garry |

Spokane Garry (sometimes spelled Spokan Garry) was an important Native American leader. He was born around 1811 and lived until 1892. Garry led the Middle Spokane tribe. He also helped connect white settlers with American Indian tribes. This happened in the area we now call eastern Washington state.

Early Life and Learning

Spokane Garry's Spokane name was Slough-Keetcha. He was born near where the Spokane River and the Little Spokane River meet. This was around the year 1811. His father was the chief of the Middle Spokanes.

In 1825, white settlers came to the area. The Hudson's Bay Company, a fur trading business, chose Garry and another boy to go to school. This school was at an Anglican mission in Fort Garry, which is now Winnipeg, Manitoba. The Missionary Society of the Church of England ran the school.

Before he left, the boy was renamed "Spokane Garry." This honored his tribe and Nicholas Garry, a leader of the Hudson's Bay Company. On June 24, 1827, he was baptized. This was one of the first Protestant baptisms for a non-white person west of the Rocky Mountains. His friend at school was Kootenais Pelly.

At Fort Garry, students learned English. They also learned new ways to survive. Garry liked learning, but new ways of life were hard. Once, he was disciplined for not following rules. He learned that white settlers could be kind. He also learned that it was often best to cooperate.

Garry's father, Chief Illim-Spokanee, died in late 1828. In the spring, Garry and Pelly left the school. They made a long journey back to the Spokane River. Garry needed to become the new chief of his tribe.

Returning to Spokane

Garry and Pelly returned to Spokane in the fall of 1829. Garry shared what he learned at Fort Garry with his people. He also taught neighboring tribes of the Columbia Plateau. The next spring, they went back to the mission. They brought five more students with them. In 1831, Garry was sent back west. He told the Kootenais that Pelly had died. Instead of returning to the mission, Garry went to Spokane and stayed there.

For the next few years, Garry taught his people. He shared his simple Anglican faith. He also taught them farming methods he learned. As chief, he felt a strong duty to his people. He wanted to ensure they lived peacefully with white settlers. Around this time, he married a woman he named Lucy.

In the 1840s, many missionaries visited the Spokanes. Some were impressed by the people's faith. Others did not like the Indians' activities. Catholic missionaries were not friendly to either group. None of them could convince the Spokanes to join their churches. Some missionaries said Garry's faith was too simple. This may have made his reputation weaker among Christians.

Later Years and Leadership

In the mid-1840s, Garry joined the first Walla Walla expedition. During this trip, a white man named Grove Cook killed a young Christian man. This man was Toayahnu, the son of Piupiumaksmaks, the chief of the Walla Wallas. The Indian agent did not seem willing to punish the crime. This made the Indians very angry. Tensions grew worse after the Whitman Massacre in 1847. Garry was a wealthy man in his tribe. He tried to keep peace between the groups.

On October 17, 1853, Garry met with Isaac Stevens. Stevens was the new Governor of Washington Territory. Stevens was surprised that Garry spoke English and French well. But he also found Garry unwilling to speak openly.

Two years later, Stevens called a meeting. The Walla Walla, Nez Perce, Cayuse, and Yakama tribes were there. Stevens wanted to make a treaty. He also asked Garry to come and watch. The chiefs agreed to a treaty, and peace seemed possible. But soon, the Yakama decided not to give up their land. They began to prepare for war against the United States. They asked younger Spokane members to join them. But Garry stopped his men from fighting. He could not stop the war, though. It began on September 23.

When Stevens heard about the war, he went to the Spokane village. He demanded to speak to Garry. Chiefs from the Coeur d'Alenes, Spokanes, and Colvilles were there. Leaders of the local French Canadian community also attended. Stevens promised friendship. But he asked the Spokanes to choose right away. They could sign a treaty and give up most of their land. Or they could declare war against the United States. He said:

I think it is best for you to sell a portion of your lands, and live on Reservations, as the Nez Perces and Yakimas agreed to do. I would advise you as a friend to do that... If you think my advice good, and we should agree, it is well. If you say, "We do not wish to sell," it is also good, because it is for you to say...

Garry gave a strong speech. He listed all the problems the Indians had. He said they did not want to give up their old lands for the white settlers. Stevens could not win the argument. He left, and the Spokanes kept their lands.

In the years that followed, Garry worked for peace. He tried to make a new treaty with the government. But his efforts were ignored. Stevens instead told the Spokanes to leave their traditional lands. He wanted them to own land individually under the Indian Homestead Act of 1862. The Spokanes did not get a reservation in the treaty they finally signed in 1887.

Legacy

In 1961, Dudley C. Carter created a carving of Garry. It is at St. Dunstan's Church of the Highlands in Shoreline, Washington. This carving honors a book about Garry. The church's vicar had written the book.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |