Stephens's banded snake facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hoplocephalus stephensii |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Elapidae |

| Genus: | Hoplocephalus |

| Species: |

H. stephensii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hoplocephalus stephensii Krefft, 1869

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Stephens's banded snake (Hoplocephalus stephensii) is a very venomous snake that lives in trees. It belongs to the Elapidae family, which includes many venomous snakes. This snake is found only in Australia, meaning it's endemic there.

Contents

About the Stephens's Banded Snake

Gerard Krefft first described the Stephens's banded snake in 1869. He named it stephensii to honor William John Stephens, an Australian academic.

What Does This Snake Look Like?

These snakes can grow up to 1 meter (about 3.3 feet) long. Some have even been seen at 120 centimeters (nearly 4 feet)! The Stephens's banded snake is the biggest snake in its group, called the Hoplocephalus genus. Adults can weigh up to 250 grams (about half a pound).

Female Stephens's banded snakes are usually a bit bigger than males. This small difference helps females have more babies.

The snake's body has cool patterns. It has stripes of grey or black mixed with dirty-white bands. These bands go all the way from its head to its tail. Its belly is mostly dirty-white, sometimes with grey spots. The top of its head is usually dark brown, and it has lighter marks on its lips.

This snake has a slender body and a head shaped like an arrow. This shape helps it move easily through trees. It also helps the snake hunt many different animals in its ecosystem. This body design helps the snake save energy for longer periods.

Special Scales for Climbing

The Stephens's banded snake has special scales that help it climb. It has 21 rows of scales around its middle. It also has 220 to 250 belly scales. These belly scales have small notches on the sides. These notches help the snake grip branches when it climbs. It also has 50 to 70 scales under its tail.

Where Do Stephens's Banded Snakes Live?

The Stephens's banded snake lives only along the east coast of Australia. You can find them from Kroombit Tops National Park in southern Queensland down to the Gosford area in New South Wales.

These snakes usually live in forests that get a lot of rain. They prefer places away from people. They can be found up to 950 meters (about 3,100 feet) high in the mountains. Studies show they often live about 20 meters (about 65 feet) high in the tops of trees.

They can live in different types of forests and handle changes in weather. They like areas that are not too bumpy. They also look for hollow trees, thick bushes, or rocky spots to hide.

Male snakes usually roam over a larger area, about 20.2 hectares (about 50 acres). Females have a smaller home range, about 5.4 hectares (about 13 acres). Males travel more to find mates.

How Do These Snakes Behave?

Stephens's banded snakes are often described as nervous and defensive. They are mostly solitary animals, meaning they like to be alone. They only meet other snakes of their kind during mating season. Males will actively look for females to reproduce. If a female doesn't want to mate, she will coil her body tightly. This keeps the male from reaching her.

Living in Trees and Being Active at Night

The Stephens's banded snake is one of the few Australian snakes that mostly lives in trees. Other snakes in the same group, like the broad-headed snake and the pale-headed snake, also live in trees. However, Stephens's banded snakes can also live on the ground if they need to.

These snakes are nocturnal, which means they are active at night. During the day, they hide in hollows inside trees. They don't spend much time basking in the sun. This is because they are small and could be easily caught by predators. When they do bask, they usually stay partly hidden by leaves. They only bask openly when they are pregnant, have just eaten, or are shedding their skin.

Winter Sleep

In winter, Stephens's banded snakes stop eating. They go into a deep sleep called brumation for up to 5 months. They hide in tree hollows during this time. Their bodies slow down a lot, which helps them save energy. Since they are cold-blooded, they can only start digesting food again when it gets warmer.

Their body temperature can change a lot, from 11.1°C to 37.8°C (52°F to 100°F). On a typical day, their body temperature is around 28.4°C (83°F).

These snakes are most active from September to May. They can move around a lot and might use up to 30 different trees. The areas where individual snakes live can overlap. But even then, they usually avoid meeting other snakes.

Life Cycle and Reproduction

Scientists believe Stephens's banded snakes have a slow life cycle. This helps them deal with less food and colder temperatures in their habitat.

Males become ready to reproduce at 3 years old. Females take longer, becoming ready at 4 years old. Females also only have babies every two years. They have small litters compared to other Australian snakes.

In captivity, scientists have seen them reproduce in spring. Stephens's banded snakes give birth to live young. They can have anywhere from 1 to 9 babies in one litter. In the wild, a generation of these snakes lasts about 8 years.

What Do Stephens's Banded Snakes Eat?

Stephens's banded snakes are nocturnal predators. They don't eat very often. They hunt in different ways, sometimes actively searching and sometimes waiting in ambush. They eat many different animals, like bush rats, pygmy possums, small lizards, mice, and frogs.

They often hide in tree hollows where small mammals live. They might coil up in a rodent's nest, waiting for the animal to return.

The types of prey they can find change with the seasons. Since these snakes are not very big, they can't eat adult animals of most prey species. Instead, they hunt young animals throughout the year. Their mouths aren't big enough for larger prey.

Baby Stephens's banded snakes are quite large when they are born, about 25 centimeters (10 inches) long. This large size helps them eat a wider variety of small cold-blooded animals and rodents. This is helpful in their environment, where food might be scarce.

Snake Venom and Safety

The Stephens's banded snake is known to bite easily. Its venom can be very dangerous. The venom causes a problem called venom-induced consumption coagulopathy (VICC). This means the blood starts to clot too much.

Symptoms of VICC include feeling sick, headaches, stomach pain, throwing up, and sweating a lot. The venom makes a special enzyme that causes tiny clots in the blood. These clots can block blood flow. If not treated, the blood vessels can break, leading to lots of bleeding.

There is no specific antivenom made from the Stephens's banded snake's venom. However, doctors have successfully treated bites using tiger snake antivenom. Up to 4 doses of this antivenom have been used.

Even though the venom is dangerous, there has only been one recorded death from a bite. This happened to an elderly man in New South Wales. He was bitten during heavy rain and floods. Rescue teams tried to get him to the hospital, but he couldn't be saved in time.

Threats and Protecting These Snakes

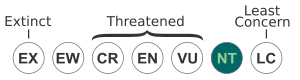

The Stephens's banded snake is listed as "near threatened" on the IUCN Red List. Over the last 200 years, since people from Europe came to Australia, the number of these snakes has gone down.

Scientists use tracking devices to study how these snakes move. They think the snake's population is shrinking mainly because their homes are being broken up. This is due to things like cutting down forests and building new towns or farms. Also, these snakes don't have many babies and grow slowly.

Sometimes, people illegally catch these rare snakes to sell them. This also harms the wild populations. New animals brought into Australia can also spread diseases and compete for food.

To help these snakes, the New South Wales government has a program called ‘Saving Our Species’. This program aims to connect and regrow the snake's broken up habitats.

Keeping Stephens's Banded Snakes as Pets

In New South Wales, people are allowed to own these snakes as pets. However, you need a special license (R3, R4, or R5 Level) from the government. To get this license, you must show proof of first-aid training. You also need a secure enclosure that the snake cannot escape from. You must have a lockable room and a plan for emergencies. Plus, you need references that show you have experience handling venomous reptiles.

Studies of snakes kept in captivity show that they can grow larger and have babies more often than wild snakes. This is because they have a steady supply of food.