Swedish famine of 1867–1869 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Swedish famine of 1867–1869 |

|

|---|---|

| Country | Sweden |

| Period | 1867–1869 |

| Observations | cold weather, drought |

The Famine of 1867–1869 was the last major famine in Sweden. It was also one of the last big famines in Europe caused by natural events, like bad weather. Another similar famine happened in Finland around the same time (1866–1868).

In Sweden, people called the year 1867 Storsvagåret, which means 'Year of Great Weakness'. In some areas, like Tornedalen, it was known as Lavåret ('Lichen Year'). This was because people had to make bark bread from lichen to survive. This difficult time led many Swedes to move to the United States.

Contents

Why Did the Famine Happen?

Sweden had several bad harvests in the 1860s. The spring and summer of 1867 were extremely cold across the whole country. In one place called Burträsk, people couldn't even start planting crops until Midsummer (late June). There was still snow on the ground!

This late spring was followed by a very short summer and an early autumn. This meant crops didn't grow well. It also made it hard to find enough food for farm animals. Because of this, food prices went up a lot.

The famine spread across Sweden, but it was worst in the northern parts. Early ice and snow made it difficult to move food supplies. This meant emergency help couldn't reach the hungry areas easily.

In 1868, a widespread drought hit the country. This caused another failed harvest and left animals starving. So, the famine continued for another year.

How Did People Try to Help?

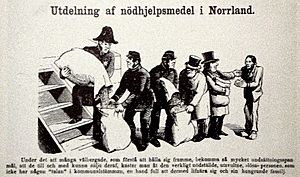

In late 1867, the Swedish government offered emergency loans to the northern counties. They also encouraged local leaders to create "emergency committees." These groups collected money from volunteers and people who wanted to help.

The government also set up two main emergency committees. One was in the capital city, Stockholm, and the other in Gothenburg. Newspapers asked people for donations. Charity concerts, plays, and other events were held to raise money for famine victims.

Help also came from outside Sweden, from both Europe and America. Reports say that foreign donations were about as much as the money raised inside Sweden. Famous people like Jenny Lind gave 500 kronor. John Ericsson gave a large sum of 20,000 kronor.

Rules for Getting Help

Local city councils gave out the help from these committees. At the time, there was a law called the Poor Care Regulation of 1847. This law was supposed to help anyone who needed it.

However, in reality, getting help was very difficult. Authorities and important people made strict rules. They thought the 1847 law was too generous. A new, stricter law was even planned for 1871.

To get help, you had to be willing to work. If you were starving but wouldn't work, you didn't get food. The only exceptions were people who couldn't work, like the elderly or those with disabilities. But even then, only 10% of the emergency money could be used for "charity" without work. The rest had to be given to people who worked for it.

So, jobs like building roads or making handicrafts were set up. This gave people a chance to work for the help they needed. These tasks were often symbolic. They showed that the government would only help those who were seen as productive.

Problems with Help Distribution

Some local councils were criticized for being too strict. They followed the "work for help" rule so closely that the neediest people didn't get any help. For example, in the parish of Grundsunda, people who couldn't offer a Surety (a promise to pay back later) received no help.

The local governor, Per Grundström, wrote about the situation. He said that many beggars and very poor people got nothing. He noted that "Torp-dwellers and other undesirables were in fact left without much at all."

Authorities even suggested that starving people should eat Bark bread made from lichen. They didn't want to give out too much flour. Some local committees, like the one in Härnösand, mixed flour with lichen. They baked it into bread before giving it out. But this bread caused chest pains and made children vomit.

What Happened After the Famine?

Newspapers strongly criticized how the relief money was given out. They said it was unfair and ineffective. The paper Fäderneslandet was especially angry. It pointed out that the people who needed help most were left out. This was because authorities refused to bend the "work for help" rule. The paper called this rule "quasi philosophical thoughts about the value of work."

Many people believed the famine was worse because food wasn't shared fairly. This idea was supported by the fact that 1867 was actually a good year for Swedish cereal exports. The largest farms and estates sold their harvests, mostly oats, to Great Britain. These oats were used to feed horses pulling buses in London.

The authorities chose to interpret the Poor Care Regulation of 1847 very strictly. This made the famine worse than it needed to be. A few years later, the 1847 law was replaced by the very strict Poor Care Regulation of 1871. This new law followed the harsh rules that the elite had used during the famine.

The great famine of 1867–68, and the anger about how the government handled the help, likely led to a huge increase in Swedish emigration to the United States. Many people left Sweden around this time, seeking a better life.

In Books and Media

- The book Svälten: Hungeråren som formade Sverige describes this famine.

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |