Thames and Medway Canal facts for kids

The Thames and Medway Canal is an old canal in Kent, south east England. It was also known as the Gravesend and Rochester Canal. It was about 11 km (7 mi) long. The canal cut across the Hoo Peninsula, connecting the River Thames at Gravesend with the River Medway at Strood.

People first thought of building this canal in 1778. It was meant to be a shortcut for military boats. These boats traveled from Deptford and Woolwich Dockyards on the Thames to Chatham Dockyard on the Medway. The canal would save them a long 74 km (46 mi) journey around the peninsula and through the Thames estuary. The canal was also planned for regular boats carrying goods between the two rivers.

Contents

Building the Canal

Early Plans and Challenges

The first real attempt to build the canal started in 1799. An engineer named Ralph Dodd shared his ideas and looked for people to invest money. Dodd's plan was for a 6-mile canal with special water gates called locks. He thought it would take two years to build and cost about £24,576. Part of the money would come from selling the dug-out chalk, which could be used to help farms. Dodd believed the canal would be useful for the government and for businesses.

In 1800, the canal company got permission from Parliament to start work. Building began at the Gravesend end. But the cost had already gone up to £57,433.

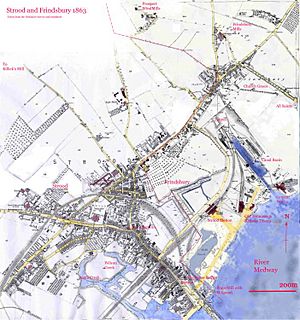

From the Gravesend area, the canal started with a straight part. By 1801, it reached about 6.5 km (4 miles) to Higham. A new engineer, Ralph Walker, arrived. He said the whole canal would cost much more than expected. Work stopped, and by 1804, Dodd had likely left the project.

Finishing the Canal

Over the next few years, Walker suggested two new paths for the Higham to Strood section. He got permission and raised money for these. His second path was chosen, but it needed a tunnel through the chalk hills. Work on this tunnel did not begin until 1819.

The canal finally opened on October 14, 1824. By this time, the Napoleonic wars were long over, so the military didn't need the canal as much. The canal project needed five Acts of Parliament (special laws) and cost about £260,000.

How the Canal Worked (and Didn't)

The canal was 13 meters (43 feet) wide. It was built for the Thames sailing barges, which were common on both rivers. The canal was supposed to carry crops like hops and other local goods. However, it did not make much money.

Water Problems

The canal had locks at each end. These locks helped keep the water level steady and protected it from the changing tides. But the canal walls leaked, and the water level would drop between every high tide. A special pumping station, powered by steam, had to be built to fix this problem.

Tunnel Troubles

Boat owners then complained that the tunnel was too slow to use. So, in 1830, it was closed for two months. During this time, a 100-yard long open-air section was dug in the middle. This split the tunnel into two separate parts: the Higham tunnel and the Strood tunnel. The fees to use the canal, called tolls, went up because of these improvements. However, if a boat missed the tide, it would have to wait in the canal basin. This wait could be longer than the journey around the Hoo Peninsula would have taken.

The Amazing Tunnel

The Higham and Strood tunnel is 3.5 km (2.2 mi) long. It was the second longest canal tunnel built in the UK. The longest is the Standedge Canal Tunnel. It was also the biggest tunnel of its kind. It was 10.7 meters (35 feet) high from the arch to the canal bed. It was 6.6 meters (21.5 feet) wide at the water line and had a towpath 1.5 meters (5 feet) wide. The water was 2.4 meters (8 feet) deep. These large sizes meant a 60-tonne sailing barge could fit through, even with its mast lowered.

Digging the Tunnel

The tunnel was dug through the chalk using only hand tools. Sometimes, gunpowder was used to break up the rock. Sadly, several workers died from falling rocks. At the time, the tunnel was seen as an amazing feat of engineering.

The tunnel is so perfectly straight, that a person placed at one end, may discern a small light entering at the other extremity [...] On the opening of the tunnel, a small steam passage boat was employed for the conveyance of passengers from Gravesend to Rochester, and vice versa; but as it was found to injure the towing-path of the tunnel, as well as the banks of the canal, it was discontinued. Foot passengers, however, still pass to and fro, though some caution is necessary, to avoid coming into contact with the horse, or horses, towing the barges.

—Tallis Directory

1839

From 1845, a new railway line between Gravesend and Strood began to share the tunnel with the canal. A single railway track was laid partly on the towpath and partly on wooden supports in the water.

The ride through the dreary tunnel with the dark waters of the canal beneath us, and an insecure chalk roof above our heads, enlivened as it is by occasional shrieks from the engine's vaporous lungs, and the unceasing rattle of the train, is apt to make one feel somewhat nervous; and the first glimpse of bright daylight that breaks upon us, relieves us from a natural anxiety as to the chances we run of being crushed by the fall of some twenty tons of chalk from above, or being precipitated into twenty feet of water beneath, with the doors of the carriages locked and no "Nautilus belt" around our waists and not even a child's caul in our pocket. This relief is however temporary, for the light only breaks in through a gap in the tunnel, and some more experienced traveller informs us we are only half out of it. However, our journey is brought to a close without any accident: and we embark on the steamer that is to deposit us at Chatham.

—William Orr, 1847

Railway Takes Over

In 1846, the canal company sold the tunnel to the South Eastern Railway company. The railway company filled in the canal inside the tunnel and laid a double railway track over it. This became part of the North Kent Line. The house of the canal's towing contractor was turned into the ticket office for Higham railway station.

William Orr's worries about falling chalk were not wrong. Over the years, there have been many small roof falls. In December 1999, a fall near Strood caused a train to go off its tracks. Luckily, no one was seriously hurt. By this time, about 60% of the tunnel had been lined (strengthened). In 2004, the tunnel was closed to line the rest of it and replace the tracks. It reopened a year later on January 17, 2005.

The Canal Today

What's Left of the Canal

The rest of the canal, between Higham and Gravesend, was used until 1934. It was damaged by bombs during World War II. Some parts have been filled in, or are now full of reeds. The Strood canal basin, which was left alone after the tunnel was filled, was also filled in during 1986. Buildings have now been built on top of it.

Since 1976, the Thames & Medway Canal Association (TMCA) has looked after the canal. They have cleaned out some areas by dredging (removing mud and rubbish). British Rail also fixed one of the swing bridges. The towpath, which is a path next to the canal, has recently been fixed up for people to walk and cycle on. It is now part of Route 1 of the National Cycle Network, which goes from Dover to John o' Groats. For walkers, it is part of circular walks connected to the Saxon Shore Way.

Plans for the Future

There are now plans to fully fix up the canal. The idea is to make it a main feature of new building projects in Gravesend. This would help the town and also meet the needs of the Thames Gateway project, which involves building new homes. In October 2004, the Gravesend canal basin was dredged. After that, the lock gates into the Thames were repaired. This means boats from the river can now use the basin. The path of the canal has been protected from new buildings since 1992.

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |