Thames sailing barge facts for kids

A Thames sailing barge is a special type of sailing boat that was once very common on the River Thames in London. These unique flat-bottomed boats were perfect for the shallow waters and narrow rivers of the Thames Estuary. They had a shallow bottom and special side boards called leeboards, which helped them steer.

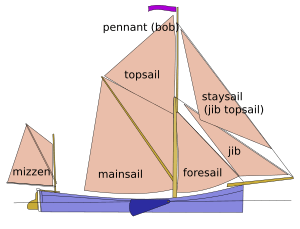

Larger Thames barges were strong enough to sail on the open sea, and they were the biggest sailing ships that could be managed by just two people! A typical barge weighed about 120 tons and had a huge sail area, about 4,200 square feet (390 m2) of canvas spread across six working sails. The main sail was loose at the bottom and held up by a pole called a sprit. It could be quickly folded up to the mast when not needed. Both the main sail and the front sail (called the foresail) were attached to a special bar, which meant they didn't need much adjusting when the boat changed direction. Sometimes, the mate (the captain's helper) would hold the foresail back to help the barge turn faster.

The topsail was usually the first sail put up and the last taken down. It was attached to the top mast with hoops. In narrow parts of rivers or busy harbors, this sail could catch the wind high above buildings or other boats. When approaching a dock, letting go of its rope would make it drop quickly, stopping the boat's forward movement. The small sail at the back, called the mizzen, helped with steering.

The masts of these barges were set in special frames called tabernacles. This allowed them to be lowered so the barges could pass under bridges. A special winch was used to lower and raise the masts, which was a lot of hard work! Sometimes, people called 'hufflers' would come aboard to help with this job for a fee. If a barge had a bowsprit (a pole sticking out from the front), it could also be lifted up to save space when docking.

River barges mostly worked on the London River and in the Port of London. Smaller "cut barges" could even go into the Regent's and Surrey canals. The larger estuary barges were strong enough for the sea and sailed along the coasts of Kent and Essex. Some even traveled further, to the north of England, the South Coast, the Bristol Channel, and to ports in Europe. They carried all sorts of things: bricks, cement, hay, rubbish, sand, coal, grain, and even gunpowder. Timber, bricks, and hay were stacked on deck, while cement and grain were carried loose inside the boat. They could sail very low in the water, sometimes with their sides almost underwater!

Thames barges sailed slowly for about 200 years. But in the 1860s, special barge races began. This led to barges being built with better designs to win, making them faster and more efficient. The Thames barge races are now the second oldest sailing competition in the world, right after the famous America's Cup.

Contents

Building and Design of Thames Barges

Most Thames barges were made of wood, though later on, some were built from steel. They were usually between 80–90 ft (24–27 m) long and about 20 ft (6.1 m) wide. Their shape was very unique: they had a flat bottom with no outside keel (the fin-like part under a boat). The sides flared out a bit, and the front and back were straight. The back of the boat, called the transom, was shaped like a champagne glass, and a large rudder was attached to it for steering.

The main part of the barge was a large hold for cargo, with two small living areas at the front and back. There were two big openings on the deck to access the hold. To stop the barge from drifting sideways in the wind, it had two large, movable leeboards on its sides.

These barges usually had two masts with a special type of sail called a spritsail rig. Most had a topsail above the huge mainsail and a large foresail at the front. The smaller mizzen mast at the back had a single sail mainly used to help steer when turning. This rig also allowed them to have a lot of sail area high up on the mast, which was great for catching wind when other ships, buildings, or trees blocked the wind closer to the water. The topsail could even stay up when the main sail was folded to the mast.

The size of the sails varied from 3,000–5,600 square feet (280–520 m2) depending on the barge. The sails often had a rusty-red color. This was because of a special mixture used to treat them, traditionally made from red ochre, cod oil, urine, and seawater. The red ochre helped protect the sails from the sun's harmful ultra-violet rays. Sails that were stored away, like jibsails, usually weren't treated.

Thames barges didn't need heavy ballast (weight added to the bottom of a boat to keep it stable). When sailing without cargo and with their leeboards raised, they only needed about 3 feet of water. This shallow depth sometimes surprised modern yacht owners who would run aground trying to follow them! Originally, barges didn't have engines, but many were fitted with them later. However, some famous surviving barges, like Mirosa and Edme, have never had engines.

The mast was placed in a "tabernacle" on the deck. It could be lowered and raised even while the boat was moving. This allowed the barge to "shoot bridges" – meaning it could pass under bridges on the Thames and Medway rivers without stopping. If there wasn't a dock available, the barge could use the outgoing tide to settle on the mud near the shore and unload its goods onto carts. A barge without a topsail, called a stumpy-rigged barge, needed a smaller crew. Because they didn't need ballast, they could load and unload cargo much faster. If a barge had a bowsprit, it could also be lifted up to allow the boat to use shorter docks.

In good weather, sailing barges could reach speeds of over 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). Their leeboards made them very good at sailing against the wind. The unique spritsail rig meant that any combination of sails could be used. Often, just the topsail alone was enough to move the boat.

History of Thames Barges

The boats that came before the Thames sailing barge were called London lighters or dumb-barges. These flat-bottomed boats moved cargo up and down the river, using the incoming tide to go upstream and the outgoing tide to return. Two bargemen would use long oars to steer them. These early barges had a flat front or a square, sloping back. A picture from 1764 shows a round-fronted barge from 1697 with a spritsail rig, but no mizzen sail.

The spritsail and leeboards both came from the Netherlands and were seen on the London River by the 1600s.

Smaller barges without a mizzen sail were called luff barges. They were more streamlined and mostly worked in the upper parts of the Thames.

In the 1800s, an artist named EW Cooke drew many pictures of barges on the river, showing all the different types of sails they used.

The flat-bottomed design made these boats very useful and cheap to operate. They could float in as little as 3 ft (0.91 m) of water and could sit upright on the river mud when the tide went out. This allowed them to go into narrow rivers and creeks to pick up farm goods, or to sit on sandbanks and mudflats to load materials for building and brickmaking. It's no surprise that they were most used when London was growing very fast! The main mast could be lowered to pass under bridges. Also, unlike most sailing boats, these barges could sail completely empty (without ballast), which saved a lot of time and effort.

While the spritsail rig was most common, some barges had a sloop rig (with a gaff and an overhanging boom), and some were ketch rigged (with two masts, the back one shorter than the front). "Mulies" had a spritsail on the main mast and a gaff rig on the mizzen. "Dandy rigs" had a spritsail on the main and a lugsail on the mizzen.

The design of the hull changed over time: decks were added around 1810, the round bow became common around 1840 and a straight front by 1900, and the square back (transom stern) replaced the sloping back around 1860.

The first Thames Barge Races happened in 1863, 1864, and 1865. These races continued every year until 1938. The person who started them, William Henry Dodd, wanted to make bargemen more respected and to improve how barges performed. There were two classes: one for smaller "stumpies" (under 80 tons) and one for heavier topsail barges (under 100 tons). These races were very competitive, and new barges were soon built using the improved techniques learned from the races, all to win the next year! The Medway races started in 1880.

The peak of Thames barges was around 1900, when over 2000 were registered. After that, their numbers slowly went down. The last wooden barge, SB Cabby, was built in 1928. The last Thames barge to carry cargo only by sail was the Cambria in 1970, owned by the famous folk song collector Captain A. W. (Bob) Roberts.

After the Second World War, the trade carried by coastal barges decreased as more goods were moved by road instead of by sea. This made it harder for barge owners to make money, so most barges were given motors and used for shorter trips within the Thames Estuary.

Trading Goods on the Thames Barges

Many goods were brought into London by barge, like building materials. Bricks came from Essex and Kent, cement from Kent, and sand was dug by the bargemen from sandbanks in the estuary. When the barges reached London Bridge, their masts were lowered with the help of 'hufflers' (strong helpers) so they could pass under to docks in the Pool of London or even further upstream to Westminster. At the dock, the cargo was unloaded by horse and cart. While a cart could carry about one and a half tons, a barge could carry 80 to 150 tons, with 120 tons being the most common.

Hoy Companies

Before Thames sailing barges became so common, there was already a good trading system along the estuary. Each port had a "hoy company" that would send boats called hoys (open square-sail barges) to London weekly to deliver or pick up goods. They would typically arrive in London loaded on Monday, unload, and return on Thursday with new cargo, getting home for Sunday. By the 1880s, they were competing with steam trains but could offer prices four or five times cheaper.

The Hay and Dung Trade

All transport in London used horses, which needed huge amounts of hay and straw. And in return, they produced a lot of dung!

The 'Stackie' was a special type of barge made for this hay and dung trade. The inside of the boat would be filled with root crops, and hay would be stacked high on the deck, sloping inwards. This stack, about 12 feet (3.7 m) high, would be covered with a tarpaulin and tied down. The main sail had to be smaller to clear this stack, and the front sail would be tied to a temporary wire. Often, the stack would even hang over the sides of the boat, blocking the view from the steering wheel. This meant the captain and mate had to communicate very well to sail such a difficult load in a busy river. On the way back from London, the hold would be filled with dung, which was useful for farmers but a problem in London.

The Mirosa, built in 1892, was once a stackie barge. She has been raced and chartered since the 1970s and is one of the few remaining Thames sailing barges that has never had an engine. The Dawn, built in 1897, was also a stackie. She has been restored and is sailing again. Stackies are popular with model-makers, and two models, Venta and British King, are often shown at the Thames sailing barge museum.

Cut Barges

The smallest river barges were designed to trade up the Regent's and Surrey canals. They could carry 70-80 tons and were only 14 feet (4.3 m) wide. They were "stumpies" (without a topmast) with a high main sail. They had very little curve in their deck because they had to pass under very low bridges. They would store their leeboards and lower their masts flat on the deck. When empty, the barge would sometimes be partly filled with water to make it sit lower and gain a few extra inches of clearance for a bridge or tunnel.

Cement Barges

These were the Kentish Barges from along the Medway River. Chalk was dug between Aylesford and Strood, and the barges would take the chalk to the many cement works in the area. Then they would carry the cement to London. There was also brick and cement work along the Swale river. At Teynham, Charles Richardson made bricks that were used in the railway bridge from Greenwich to London. Cement from his factories in Conyer was even sent from London to New Zealand. These barges were easy to spot because they were covered in ash and cement dust from lying near the cement works. Also, the mud in Kentish creeks like Conyer and Milton would stain clean paint.

Kentish barges didn't need bowsprits as much as the Essex barges, which found them helpful for the long journey along the Swin (Thames).

Grain Barges

A main job for barges was moving grain. They would pick up grain unloaded from large ships coming from other countries and take it from London ports to mills or malt factories at the end of many tidal creeks on the East coast and around the Thames estuary. Grain was also taken to London mills further upstream, like the City Flour Mills at Puddle Dock, which was said to be the largest in the world when built in the 1850s. Grain could be carried loose in the hold or in bags. Barges delivering grain out of London would then look for a suitable cargo to bring back to London so they didn't return empty. A well-known example of a grain barge is the SB Kathleen, a 59-ton barge built in 1901. She was built for carrying a lot of cargo rather than for speed. She was 82.8 feet (25.2 m) long and 19.7 feet (6.0 m) wide. When empty, she needed 30 inches (76 cm) of water, and when full, 6 feet (1.8 m).

Brick Barges

Bricks were made using heavy clay from Essex, or clay from along the Swale, mixed with local chalk and "breeze" (ash from London rubbish). This ash was brought by barge to Teynham, Lower Halstow, and Conyer. The finished Kentish yellow bricks then went back to London. A large barge-building industry grew in Sittingbourne. These barges could carry 100 tons, holding 40,000 to 42,000 bricks, and were box-shaped.

Coastal Barges

Portland stone was brought from quarries in Weymouth, around the North Foreland, into the Thames estuary, and up into the London River.

North Sea Barges

The North Sea was important for trade. Coal was brought from Newcastle to the shallow ports along the London River. These barges were usually schooner-rigged (with two masts, the front one shorter) but had the flat barge hull. After the Second World War, coal was still delivered to the gasworks at Margate by SB Will Everard from Goole. During the First World War, they carried coal between Goole and Calais. This was a four-day trip, carrying 200 tons. The barges were generally too shallow to set off mines.

Coastal barges made long journeys. The SB Havelock of London, built in 1858, regularly traded between Liverpool and Rotterdam.

The Barge Races

The performance of barges became much better because of the yearly sailing races. In these races, barges competed for trophies and money prizes. These matches are believed to have encouraged improvements in design, leading to the very efficient final shape of the barges. They were started in 1863 by a rich owner named Henry Dodd. Dodd was a farm boy from Hackney, London, who became wealthy by carrying the city's waste to the countryside on his barges. He might have been the inspiration for Charles Dickens's character, the Golden Dustman, in his book Our Mutual Friend. When Dodd died in 1881, he left £5000 for future race prizes.

The Thames and Medway barge matches were stopped for a while in 1963. In those races, Spinaway C won the Thames race and came second in the Medway. Memory came second in the Thames and first in the Medway. These two were the very last of the older style barges to win the classic races.

The matches have stopped and restarted several times. They are now considered the world's second-oldest sailing race, after the America's Cup. The race course originally started upriver from Erith, but by the early 1900s, the start was moved downriver from Gravesend into the Estuary and back to Gravesend.

In 2013, the Thames Match celebrated its 150th anniversary, and to mark the occasion, the finish line was at Erith. There was a full schedule of races in 2017 on the Medway and Thames.

The 109th Medway barge race took place on Saturday, June 3, 2017. The course was 29 miles (47 km) long, starting from Gillingham Pier, following the channel to the Medway buoy east of the Nore in the Thames, and returning to Gillingham. The 110th race was planned for May 19, 2018.

Operation Dynamo – The Dunkirk Evacuation

Thirty barges were part of the fleet of 'Little Ships' that helped rescue soldiers of the retreating British Expeditionary Force from the beaches of Dunkerque during World War II. The flat-bottomed barges could reach the shallow beaches and pick up troops, taking them to larger ships waiting further out at sea. These larger ships would then make the journey across the English Channel.

Twelve barges were sunk, but eighteen vessels returned. One of these, SB Pudge, was damaged by a mine but has been repaired and is still used on the rivers today. Another, Ena, had her crew taken off and was supposed to be left behind in France, but a group of soldiers with only holiday sailing experience managed to float her and sail her home. The oldest 'Little Ship' still active is the barge Greta, built in 1892.

| Name | Official number | Year | Location | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ada Mary | 049850 | 1865 | Frindsbury | Returned |

| Beautrice Maud | 129112 | 1910 | Sittingbourne | Returned |

| Cabby | 160687 | 1928 | Frindsbury | Returned |

| Ena | 122974 | 1906 | Harwich | Returned |

| Glenway | 127260 | 1913 | Rochester | Returned |

| Greta | 98324 | 1892 | Colchester | Returned |

| H A C | ??? | |||

| Haste Away | 086628 | 1886 | Harwich | Returned |

| Lady Sheila | ??? | |||

| Monarch | 113687/ 120492 | 1900/1905 | Sittingbourne | Returned |

| Pudge | ||||

| Queen Alexandra | 115856 | 1902 | East Greenwich | Returned |

| Seine | ??? | |||

| Shannon | 109920 | 1898 | Milton Regis | Returned see also 105792/ 25632 |

| Sherfield | ??? | |||

| Spurgeon | 087219 | 1883 | Murston | Returned |

| Thyra | 127262 | 1913 | Maidstone | Returned |

| Tollesbury | 110315 | 1901 | Sandwich | Returned |

| Viking | 104319/ 114764 | Returned | ||

| Vessels lost | ||||

| Aidie | 1924 | Brightlingsea | lost | |

| Burton | 081867 | 1880 | Murston | lost |

| Barbara Jean | 149251 | 1924 | Brightlingsea | abandoned lost |

| Claude | 076584/(017556) | 1876 | Sittingbourne | lost |

| Doris | 113759 | 1904 | Ipswich | abandoned 3 n.m E of beaches |

| Duchess | 118372 | 1904 | East Greenwich | lost |

| Ethel Everard | 149723 | 1926 | Great Yarmouth | lost |

| Lady Rosebery | 127268 | 1917 | Rochester | lost |

| Lark | 112735 | 1900 | Greenhithe | lost |

| Queen | 089574/??? | 1884 | Limehouse | lost |

| Royalty | 109919 | 1898 | Rochester | lost |

| Valonia | 132631 | 1911 | East Greenwich | lost |

| Warrior | ??? | lost |

How Thames Barges Were Built

Thames barges were built to be very strong. They had flat bottoms so they could easily be pulled onto a beach or rest on the river mud. Their sails were designed so that just two men, and maybe a boy, could operate them. They were built in special bargeyards next to a river or creek. These yards had "bargeblocks" – raised platforms about a meter high – which allowed workers to build the boat from above and below.

The smallest barges were river barges, carrying about 100 tons. Estuary barges were usually heavier, 120-140 tons, and coastal barges could carry 160-180 tons. The largest barges, like the four Everards barges and the Barbara Jean and Aidie, could carry 280 tons.

Barges were made only of wood until 1900, when the first steel barges appeared. During its working life, a barge might be "doubled" or "boxed" – meaning a second layer of planks would be added over the first for extra strength.

The Kathleen, a typical grain barge built in 1901, became famous because her detailed measurements were published in books. Over time, her sails were changed to fit new trading needs.

The main beam at the bottom, called the keel, was a piece of elm wood 12 by 4 inches (30 by 10 cm) and 82.8 feet (25.2 m) long. At the front, the stempost stood up straight, and at the back, the sternpost. These were made from 6 feet (1.8 m) lengths of 12 by 9 inches (30 by 23 cm) English oak. Inside, other timbers strengthened the boat's shape.

Across the keel were laid the floors, which were 8 by 6 inches (20 by 15 cm) oak timbers placed about 20 inches (51 cm) apart. Most of these floors were 19.7 feet (6.0 m) long, the same as the barge's width. On top of the floors, on earlier barges, a huge Oregon pine beam called a keelson was bolted. On Kathleen, the keelson was a steel section, cheaper but could bend.

The side frames, called futtocks, were joined to the ends of each floor. These were 8 by 6 inches (20 by 15 cm) oak timbers, averaging 6 feet (1.8 m) long. Temporary poles held the futtocks in place until the shipwright approved the shape. Then, temporary strips of wood called ribbands were nailed to the outside of the frames to hold them. Inside, strong timbers called inner chines were bolted to the floors and futtocks, and above them, an oak stringer was bolted to the futtocks.

Inside the Barge

Pine planks, 3 inches (7.6 cm) thick, were laid on the floors to form the "ceilings" (the inner bottom of the hold). The height of the deck was marked on the frames, and a strong oak beam called an inwale was bolted to the futtocks. The inside of the hold was lined with 2 inches (5.1 cm) thick pine. The inwale created a ledge for the curved deck beams and other supports. Because of the two large holds, regular deck beams couldn't be used alone. There were beams at the front hold, under the mast, between the main hold and the cabin, and supporting the back. On the Kathleen, the decks on the port (left) and starboard (right) sides were different widths.

Leeboards and Rudder

The leeboards are a key feature of Thames barges. They are needed because the barges don't have a keel to stop them from moving sideways. On the Kathleen, they were made of 3 inches (7.6 cm) thick oak and reinforced with seven iron straps. Each weighed about 25 long hundredweight (1,300 kg), was 18 feet (5.5 m) long, and had an 8 feet (2.4 m) fan shape. They pivoted from the side of the boat and could drop 5 feet (1.5 m) below the hull. They were raised using two special winches. Partially raised leeboards could even be used to help steer, and in shallow waters, the barge could turn by dragging a leeboard in the mud.

The rudder was attached to a 12 inches (30 cm) square, 11 feet (3.4 m) oak rudderpost. The rudder blade was 7 feet 4 inches (2.24 m) wide, made of boards that got narrower from 12 inches (0.30 m) to 6 inches (0.15 m). On older, smaller boats, there was a 12 feet (3.7 m) long handle called a tiller. On some barges, ropes or chains and pulleys were attached to the rudder post and connected to a traditional ship's wheel. On most barges, the rudder was connected to the wheel by a special gear that allowed some looseness. Some barges had an all-metal ship's wheel, which was called a "chaff cutter" because it looked like a farm tool.

The Sail Rig

When she was built, Kathleen had a bowsprit, a main mast, and a mizzen mast. She had spritsails on both masts and a topsail on the main mast. In 1926, she was changed to sail without a bowsprit. In 1946, she lost her mizzen mast when an engine was added. By 1954, her sails were reduced to that of a motor barge, and from 1961 to 1965, she was used as a lighter (a boat for moving goods short distances), with her engine and mast removed. When she was converted into a barge yacht for races in 1966 and 1967, her sails were similar to how they were in 1926.

This was the classic spreetie rig. Early spritsail barges were rigged without a top mast; these were called stumpies. They raced in a separate class in the Thames barge race until 1890.

The loose-footed spritsail was good for river work. This rig also allowed for a tall stack of cargo on deck. The entire sail could be quickly folded to the mast, giving clear access to the deck and hold for loading and unloading. Barges don't have ballast, so if there's too much wind, they will lean too much and must turn into the wind. If the rope holding the sail (the sheet) is loosened, the back end of a boom would drag in the water, making the rudder useless and causing the boat to tip over. But with a loose-footed main sail, the sheet is simply released, and control is immediately regained.

Since there's no boom sticking out, the boat can pass through narrow gaps between other moored boats. Loose-footed sails are not as good at sailing against the wind, but this usually wasn't a problem for carrying cargo. Ropes called vangs control the top of the main sail and act as sheets for the topsail. The topsail can be set high to catch the wind above the shadows of other ships, warehouses, and local features.

The two-person crew could quickly shorten the sails even in rough seas. The topsail was on hoops, so its rope was let go, and the sail dropped. The mainsail was pulled tightly to the mast by special ropes called brails. The vangs were loosened, the sheet released, and the sail was "brailed up" by the mate using a winch. The mate would let go of the foresail ropes, and it would drop to the deck. If the barge was going to beach, the winches were used to lift the leeboards to stop them from hitting the bottom. The anchor was dropped. The barge could then be unloaded onto the sand when the tide went out. The sails were secured, and the sprit was fixed in place.

In narrow channels and behind tall buildings, the mainsail and mizzen are folded, and the bowsprit is lifted. The barge then sails only on its topsail and foresail. A gaff rig was better for bad weather and long sea journeys. However, when a gaff-rigged boat takes in its mainsail, it cannot set the topsail.

A boomie is a flat-bottomed ketch-barge. It had a ketch rig on both the main and mizzen masts, meaning the sprit was replaced by a gaff, and the bottom of the sail was tied to a boom. These were large barges, often built with smoother lines and a rounded back. They had a fixed bowsprit, and the mast was set deep into the boat. It took four or five men to sail them, they needed more space at the dock, and they couldn't operate on their topsail alone. So, they were better for longer sea journeys. When times were tough, some of these barges would be changed to have a sprit on the main mast but keep the gaff on the mizzen, becoming a mulie. The biggest barge ever launched in Kent, Eliza Smeed (1867), was rigged like a barquentine (a type of sailing ship) but still had leeboards.

The Thames and Medway sailing race community divides barges into two groups: staysail barges, whose foresails are attached to the main support rope, and bowsprit barges, which have a bowsprit. The barges on the Medway and London River are generally staysail barges. The larger estuary barges, which make longer trips on open water like the Swin and the Wallet channels, tend to be the bowsprit barges. Barges can change their rig and class, as the Kathleen did. For racing, extra sails like additional staysails and spinnakers can be carried.

Spars

The mainmast was made of 11-inch (28 cm) spruce wood. It was 40 ft (12 m) tall to the top and 35 ft (11 m) to the point where the upper ropes attached. The sprit, which was 10+1/2-inch-diameter (27 cm), was 59 ft (18 m) long. The topmast, 7+1/2 in (19 cm), was 39 ft 6 in (12.04 m) to its attachment point, with a 4 ft 6 in (1.37 m) pole and a 9 ft (2.7 m) headstick.

The mizzen mast, 6 in (15 cm), was 17 ft (5.2 m) tall. Its sprit, 6-inch-diameter (15 cm), was 24 ft (7.3 m), and the boom, 4-inch-diameter (10 cm), was 14 ft (4.3 m). The bowsprit, 7 in (18 cm), was 22 ft 6 in (6.86 m) long, with 14 ft (4.3 m) sticking out.

Standing Rigging

Original barges used hemp ropes for their rigging, but most barges today use wire ropes. The standing rigging held the masts and sprit in place. Since the masts were lowered and raised to clear bridges, the forestay (a main support rope) was connected to the windlass (a machine for pulling ropes). The topmast could also be lowered. The lower end of the sprit was held to the mast in a "muzzle," but lifted up by a chain called a "stanliff" or "standlift." The barge had 3-inch (7.6 cm) shrouds (side support ropes).

Sails

The mainsail was 27 ft 3 in (8.31 m) (front edge), by 34 ft 6 in (10.52 m) (top edge) with a back edge of 49 ft 0 in (14.94 m) and a bottom edge of 35 ft 6 in (10.82 m). This gave it a sail area of 285 square yards (238 m2).

The topsail was 34 ft (10 m) (front edge), with a back edge of 34 ft (10 m) and a bottom edge of 31 ft (9.4 m). This gave it a sail area of 128 square yards (107 m2).

The foresail was 31 ft (9.4 m) (front edge), with a back edge of 30 ft (9.1 m) and a bottom edge of 26 ft (7.9 m). This gave it a sail area of 91+1/2 square yards (76.5 m2). The jib was 42 ft (13 m) (front edge), with a back edge of 28 ft (8.5 m) and a bottom edge of 18 ft 4 in (5.59 m). Her jib topsails were 48 ft (15 m) (front edge), with a back edge of 33 ft (10 m) and a bottom edge of 21 ft (6.4 m), giving a sail area of 55 square yards (46 m2). A lighter set had a front edge of 56 ft (17 m), a back edge of 38 ft (12 m), and a bottom edge of 24 ft 6 in (7.47 m), giving a sail area of 72 square yards (60 m2).

Her mizzen sail was 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m) (front edge), by 12 ft 0 in (3.66 m) (top edge) with a back edge of 23 ft 6 in (7.16 m) and a bottom edge of 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m). This gave it a sail area of 285 square yards (238 m2).

The sails on a Thames barge are a reddish-brown color because of the red ochre used to treat them. The sailcloth is made of flax, and it needs to be treated to stay flexible and waterproof. It's important that the flax doesn't dry out, or it will rub and wear out against the rigging or the brails when not in use.

Preserving Thames Barges

Inspired by a book about the Norfolk Wherry Trust, the Thames Sailing Barge Trust was started on April 15, 1952. It was founded in the cabin of the sailing barge George Smeed. The trust bought the sailing barge Memory in 1955 and used it to carry cargo until 1960, when the trust was closed. (Note: This trust is not the same as the current organization with the same name.)

Memory was then bought by Sailtrust Limited, a company formed by John Kemp and Brian Beer. Following a suggestion, she was changed to be an adventure training ship. However, the company couldn't make enough money from adventure training, so they used Memory for weekend charters, with John Kemp as the captain. Memory was the first sailing barge to be used for charter trips.

In April 1965, Sailtrust Ltd signed a contract with the London Borough of Redbridge to take groups of schoolchildren sailing every week from April to October. This contract lasted for eleven years. In the second year of this contract, the Board of Trade made rules stricter for charter vessels, and Memory could no longer be used for that purpose. She was replaced by the auxiliary sailing barge Thalatta, which had been a cargo ship until 1966. Both barges were captained by John Kemp. The operation of Thalatta was later taken over by the East Coast Sail Trust. The Trust then re-rigged her, using some parts from the damaged barge Memory. In 2005, the Trust had to repair her hull, and with funding, they finished the repairs in 2009. Then, in August 2011, they launched the barge again.

More About Thames Barges

- List of active Thames sailing barges

- Cooks yard – A place where barges were built and repaired in Maldon, Essex

- Mersey Flat – Another flat-bottomed cargo boat, found on the Mersey Estuary

- Norfolk wherry – Another flat-bottomed cargo boat used in rivers

- Humber Keel – Another traditional river and estuary boat

- Thames River Steamers

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |