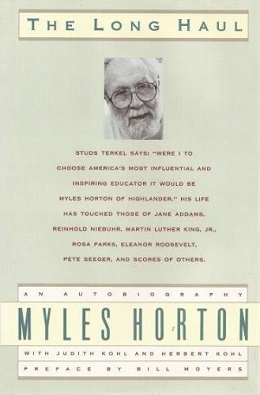

The Long Haul (autobiography) facts for kids

First edition

|

|

| Author | Myles Horton |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Autobiography |

| Publisher | Teachers College, Columbia University |

|

Publication date

|

1998 |

| Media type | Print (Softcover) |

| Pages | 228 |

| ISBN | 0-8077-3700-3 |

| OCLC | 37705315 |

| 374/.9768/78 21 | |

| LC Class | LC5301.M65 H69 1998 |

The Long Haul is a book about the life of Myles Horton. He was a special kind of teacher and leader. Myles Horton helped start the Highlander School. This school taught people how to work together for big changes in society. Highlander was important in the labor movement (workers fighting for better jobs) in the 1930s. It also played a key role in the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Horton's ideas about teaching and learning helped many people.

Contents

Myles Horton's Early Life

Myles Horton was born in Savannah, Tennessee, on July 9, 1905. His parents were not rich, but they were educated. They taught him important lessons. He learned that rich people sometimes lived off the hard work of others. He also learned that education should help you do good things for others.

He understood the power of groups working together, like unions. He also learned how important it was to care for your neighbors. As a young person, he worked at a sawmill and packed tomatoes. At the tomato job, he helped other young workers organize a strike action. They stopped working until they got a small raise. Later, he became a top student and football player in high school.

College Years and New Ideas

Horton went to Cumberland University in Lebanon, Tennessee. It was a small college. He learned to teach himself because there were not many good teachers. This helped him develop his own ideas. He started studying how workers could own and run businesses together. He also looked at local labor unions and how working people could organize strongly.

He became a socialist. This meant he believed that people who were treated unfairly should work together. They could build a new society where everyone was equal. After college, he worked for the YMCA. In 1928, he organized a meeting that included both black and white people. This was against the unfair Jim Crow laws of that time. He also started a discussion group for poor people in Ozone, Tennessee. Here, he helped people talk about their problems and find solutions together.

Learning in Graduate School

In 1929, Horton went to Union Theological Seminary in New York City. This was a school known for its new ideas. He learned from Reinhold Niebuhr, a Christian thinker. Niebuhr's ideas about doing what is right in an unfair world helped Horton think about civil disobedience. This means peacefully refusing to obey unfair laws.

Horton read many different thinkers, like Alexander Hamilton, John Dewey, Karl Marx, and Vladimir Lenin. His time in New York helped him see the world more broadly. Many of his friends there came from wealthy families. Some of them helped him start the Highlander School. He also saw protests in Manhattan. Police often broke them up roughly. This helped him think about how to use peaceful actions to make changes. He believed in practical non-violence, not just being against all force.

After New York, Horton studied at the University of Chicago. He saw how people were trying to solve social problems. He visited places like Hull House, which helped new immigrants. In Chicago, he learned that working together was not just more effective. It also helped people learn better. He also learned how important it was for everyone in a group to share their different ideas openly. He realized that people should have control over their own lives, including their education. He thought that education for people who were treated unfairly should show the kind of fair society they wanted to create.

Discovering Danish Folk Schools

While in Chicago, Horton learned about Danish folk schools. These schools started in the 1800s in Denmark. They used ideas similar to what Horton believed in. He traveled to Denmark to see them for himself. He saw schools where students and teachers learned from each other in a relaxed setting. Students learned because they wanted to, not just for tests. And the education aimed to create a fair and equal society.

Starting the Highlander School

When Horton came back to the U.S., he met with friends from Union Theological Seminary. Together, they started the Highlander School in the hills of Tennessee. This school combined all that Horton had learned. It brought together his childhood lessons, his formal education, his political work, and the ideas from the Danish folk schools.

They began by leading informal discussions for adults in the community. They talked about geography, economics, and local union issues. They also learned to understand problems from the students' point of view. They encouraged people who were never taught to value their own ideas to talk and learn together to solve their problems.

Highlander and the Labor Movement

Highlander soon started helping to organize unions in the area. They also hosted community gatherings. This made the political community stronger. Highlander began a more formal program to train union members. These were regular workers who wanted to become leaders in the union movement. Newly chosen union organizers and shop stewards studied there for weeks.

The school kept its ideas of democratic education for working people. It focused on a specific social issue: organizing workers when the government was making it hard for unions. This experience was very important for Highlander's later work in the civil rights movement.

Highlander was also the only school in the South that allowed both black and white people to study together. This was called integration. They knew it was important to teach union leaders not to let bosses turn white workers against black workers. It was also a chance for people to learn about racial equality. White and black students studied together, often for the first time. Their experience at the school showed the fair society Highlander wanted to create.

Later, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, many left-leaning people were removed from the labor movement. Unions became less interested in changing society. They focused more on getting benefits from powerful people. After the Red Scare (a time when people were afraid of communism) cut Highlander off from the main labor movement, it focused more on racial equality.

Highlander and the Civil Rights Movement

Highlander began working with African American leaders in the South. They helped start "Citizenship Schools." In these schools, black people could learn to read. They also learned how to pass tests to register to vote. These schools were a mix of Highlander's informal education ideas and what African American leaders knew their communities needed.

Highlander kept training people who wanted to start Citizenship Schools. But many more schools were started by people who had never even been to Highlander. More and more African Americans were organizing for fairness in the South. The civil rights movement was truly beginning.

The Citizenship School program was later taken over by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Martin Luther King, Jr.. But Highlander stayed a very important place for the civil rights movement. Many famous activists went to Highlander workshops. These included Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, Rosa Parks, James Bevel, and Bernard Lafayette. They talked about plans and learned tactics together. They learned from the labor movement and found their own ways forward. Ideas spread at Highlander. For example, the song "We Shall Overcome" moved from the labor movement to the civil rights movement there.

The state of Tennessee eventually closed the school in 1959. They used false reasons to do it. Highlander moved to nearby Knoxville for ten years. Then, they created another permanent school. Highlander continued to work for racial equality. Later, they also focused on protecting the environment and helping immigrant rights.