1926 United Kingdom general strike facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1926 United Kingdom general strike |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

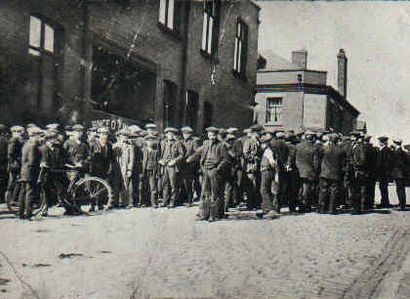

Tyldesley miners outside the Miners' Hall during the strike

|

|||

| Date | 4–12 May 1926 | ||

| Caused by | Mine owners' intention to reduce miners' wages | ||

| Goals | Higher wages and improved working conditions | ||

| Methods | General strike | ||

| Resulted in | Strike called off | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

| Number | |||

|

|||

The 1926 general strike in the United Kingdom was a huge protest by workers. It lasted for nine days, from May 4 to May 12, 1926. The Trades Union Congress (TUC), a group representing many workers' unions, called for the strike.

They wanted the British government to help prevent pay cuts and worse working conditions for 1.2 million coal miners. About 1.7 million workers joined the strike. Many of them worked in transport and heavy industries.

This was a sympathy strike. This means many workers who were not miners joined to support the miners. The government was ready for the strike. They used volunteers to keep important services running. There was not much violence. In the end, the TUC stopped the strike.

Why Did the Strike Happen?

Coal Mining Problems in the 1920s

After World War I, Britain's coal mines faced big problems. During the war, a lot of coal was used at home. This meant that many good coal areas were used up. Britain also exported less coal during the war. Other countries like the United States, Poland, and Germany started selling more coal.

Coal production in Britain was going down. In the early 1880s, each miner produced about 310 tons of coal a year. By the 1920s, this had dropped to only 199 tons.

Economic Challenges and Lower Wages

In 1924, a plan called the Dawes Plan helped Germany. It allowed Germany to sell coal to France and Italy. This extra coal made coal prices lower around the world.

In 1925, Winston Churchill, who was in charge of the country's money, brought back the gold standard. This made the British pound very strong. A strong pound made it harder for Britain to sell its coal to other countries.

Mine owners wanted to keep making money. So, they often cut miners' wages. Miners' weekly pay had been cut in half over seven years. They were also asked to work longer hours. This made the mining industry very unstable.

Miners' Demands and Government Response

When mine owners said they would cut wages even more, the Miners' Federation of Great Britain said no. Their slogan was: "Not a penny off the pay, not a minute on the day."

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) promised to support the miners. The Conservative government, led by Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, stepped in. They offered money to keep miners' wages the same for nine months.

They also set up a special group, the Samuel Commission. This group would study the problems in the mining industry. They would also look at how it affected other businesses and families.

Samuel Commission's Report

The Samuel Commission released its report in March 1926. It suggested ways to improve the mining industry. But it also said miners' wages should be cut by 13.5%. The government's money support would also stop.

The Prime Minister said the government would accept the report. But only if everyone else did too. The mine owners then said miners would get new job offers. These offers included longer workdays and lower wages. The Miners' Federation refused to accept these lower wages.

The General Strike of May 1926

Strike Begins

Talks to avoid the strike failed on May 1. So, the TUC announced a general strike. It would start just before midnight on May 3. The strike was to support miners' wages and hours.

Leaders of the Labour Party were worried about the strike. They knew some union members wanted big changes. They feared the strike would hurt the party's image.

A last-minute problem happened with the Daily Mail newspaper. Its printers refused to print an article that criticized the strike. This made Prime Minister Baldwin worried about freedom of the press.

King George V tried to calm things down. He said, "Try living on their wages before you judge them."

Who Went on Strike?

The TUC worried that a full general strike could cause too much trouble. So, they limited who would strike. They called on railway workers, transport workers, printers, dock workers, ironworkers, and steelworkers. These workers were key to the country's operations.

The government had prepared for the strike for nine months. They created groups like the Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies. This group helped keep the country running. They used the Emergency Powers Act 1920 to make sure important supplies were available.

First Days of the Strike

On May 4, 1926, about 1.5 to 1.75 million workers were on strike. Strikers were everywhere, "from John o' Groats to Land's End". The strike was much bigger than the government or the TUC expected. On this first day, transport across the country stopped.

On May 5, both sides shared their views. Winston Churchill, who edited the government newspaper British Gazette, said the TUC was trying to "wreck" the nation. Prime Minister Baldwin said the strike was a "challenge to the parliament." The TUC's newspaper, British Worker, said they were not fighting the public. They just wanted to help workers.

The government also used special constables, who were volunteers, to keep order. One volunteer later said he felt sympathy for the strikers. He had not known about the "appalling poverty" they faced.

Later Days of the Strike

By May 6, things started to change. The British Gazette said transport in London was getting better. More volunteers, car-sharing, and private buses were helping.

On May 7, the TUC met with Samuel and made new plans to end the strike. But the Miners' Federation said no to these plans. The British Worker newspaper had trouble getting paper. So, it had to print fewer pages. The government also started protecting workers who wanted to return to their jobs.

On May 8, a big event happened at the London Docks. Trucks carrying food were protected by the British Army. They broke through the picket line and delivered food to Hyde Park. This showed the government was gaining control. In Plymouth, tram services started again. Some trams were attacked, but there was also a football match between police and strikers. The strikers won 2-0!

On May 11, striking miners derailed the Flying Scotsman train near Cramlington. The British Worker tried to keep spirits up. It said the number of strikers was growing, not shrinking.

However, a court ruling weakened the strike. A judge said the general strike was not a normal trade dispute. This meant unions could be in trouble for breaking contracts.

Strike Ends

On May 12, the TUC leaders went to 10 Downing Street. They said they would call off the strike. They asked for the Samuel Commission's ideas to be used. They also wanted a promise that strikers would not be punished.

The government said they could not force employers to take back every striker. But the TUC agreed to end the strike anyway. Some smaller strikes continued as unions made deals for their members to return to work.

What Happened After the Strike?

Miners' Struggle Continues

The miners kept striking for a few more months. But they eventually had to go back to work because they needed money. By the end of November, most miners were back. However, many stayed unemployed for years. Those who found work had to accept longer hours and lower pay.

The strike had a big effect on British coal mines. By the late 1930s, the number of miners had dropped by more than a third. But the amount of coal each miner produced went up.

Changes for Unions

The strike caused some disagreements among miners. This made it harder for them to act as one group. Later, the National Union of Mineworkers was formed.

In 1927, a new law was passed called the Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act 1927. This law made sympathy strikes, general strikes, and large groups of picketing illegal.

Overall, the strike did not change unions or work relations much in the long run. The TUC and unions stayed strong. Many historians agree it was not a major turning point. There have been no other general strikes in Britain since then. Union leaders like Ernest Bevin thought it was a mistake. They believed political action was a better way to make changes.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |