Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site facts for kids

|

White Haven; Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site

|

|

|

|

| Area | 9.9 acres (4.0 ha) |

|---|---|

| Built | 1795 |

| Built by | Long, William Lindsay |

| Website | Ulsses S. Grant National Historic Site |

| Part of | Grantwood Village, Missouri |

| NRHP reference No. | 79003205 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | April 4, 1979 |

| Designated NHL | June 23, 1986 |

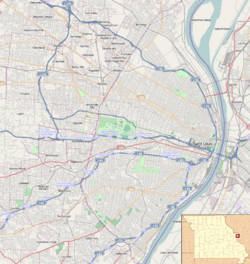

The Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site is a special place in Grantwood Village, Missouri. It covers about 9.65 acres and is located southwest of downtown St. Louis. This site, also known as White Haven, helps us remember the life of Ulysses S. Grant. He was a famous general and later became the President of the United States.

At White Haven, you can explore five old buildings. One of them was the childhood home of Julia Dent, who later married Ulysses S. Grant. White Haven was once a large farm, called a plantation, that used the forced labor of enslaved people. Grant lived here and managed the farm from 1854 to 1859.

Contents

Grant's Life at White Haven

After Ulysses S. Grant married Julia Dent, he was a soldier in different places like Michigan and New York. Julia often traveled with him. In 1850, she came back to White Haven for the birth of their first child, Fred. When Ulysses was sent to the West in 1852, Julia couldn't go because she was expecting their second child. She stayed with her parents at White Haven after visiting Ulysses's parents in Ohio, where their son Ulysses Jr. was born.

Grant's army pay wasn't enough to support his family far away. He tried different ways to earn more money. After being apart for two years, he felt sad and lonely. So, in 1854, he left the army and returned to White Haven.

Grant worked on the White Haven farm for his father-in-law, Colonel Dent. He worked alongside the enslaved people owned by Julia's father. Two more children were born here: Ellen in 1855 and Jesse in 1858. In 1857, there was a big money problem called a financial panic, and bad weather ruined many crops. Because of this, Ulysses worked for a short time in St. Louis, selling houses and as an engineer.

In 1860, Ulysses, Julia, and their four children moved to Galena, Illinois. There, Ulysses worked with his brothers, selling leather goods from their father's business.

Slavery at White Haven Farm

Many enslaved people lived and worked at White Haven. The National Park Service explains that during the 1850s, enslaved labor was used a lot to farm and maintain the 850-acre plantation. From 1854 to 1859, Grant lived here with his family and managed the farm for his father-in-law. His experiences here might have helped him later when he became a general in the American Civil War and then President.

Daily Life for Enslaved Children

In 1830, many of the people enslaved by Colonel Dent were children under ten years old. Children like Henrietta, Sue, Ann, and Jeff played with the Dent children. Julia Dent remembered them fishing, climbing trees, and picking strawberries together. However, enslaved children also had chores, such as feeding chickens and cows. As the white children went to school, the enslaved children learned their assigned tasks. Julia noticed that when the enslaved girls grew older, they started wearing "white aprons," which showed they had moved from playing to doing forced labor.

Chores in the House

Enslaved adults did many jobs inside the Dent family's house. Kitty and Rose helped take care of Julia and Emma. Mary Robinson was the family cook. Julia often praised the delicious food Mary made, like cakes, biscuits, custards, and soups. An enslaved man named "Old Bob" had to keep the fires burning in White Haven's seven fireplaces. Julia thought Bob was sometimes careless if the fires went out, because he would have to walk a mile to a neighbor's house to get a new fire starter. This "carelessness" sometimes gave Bob and other enslaved people a chance to leave the farm for a short time.

Working on the Farm

Enslaved people did most of the hard work on the 850-acre farm. They used farm machines owned by Colonel Dent to plow, plant, and harvest crops like wheat, oats, potatoes, and corn. They also took care of the fruit trees and gardens, growing food for everyone on the property. When Grant managed the farm, he worked alongside Dan, an enslaved man who had been given to Julia when she was born. Grant, Dan, and other enslaved people cut down trees and took firewood by wagon to sell in St. Louis. They also cared for over 75 horses, cattle, and pigs every day. Enslaved people also helped maintain the grounds and worked on remodeling projects for the main house and other buildings.

Finding Freedom

Mary Robinson, an enslaved woman at White Haven, said in 1885 that Grant "always said he wanted to give his wife's slaves their freedom as soon as he was able." In 1859, Grant freed William Jones, who was the only person he is known to have enslaved himself.

During the Civil War, some enslaved people at White Haven simply left the farm to find freedom, just like on many other plantations. In January 1865, the state of Missouri officially ended slavery. This meant that any enslaved people still living at White Haven were finally free.

Grant wrote, "I Ulysses S. Grant... do hereby manumit, emancipate and set free from Slavery my Negro man William, sometimes called William Jones... forever."

After Grant Left White Haven

In 1881, the Grants gave White Haven to William Henry Vanderbilt. This was to pay back a loan Vanderbilt had given Grant after one of Grant's business partners stole investment money. Later, a part of the farm was bought by Adolphus Busch, who created his famous Grant's Farm property there.

In 1913, Albert Wenzlick, a real estate developer from St. Louis, saved the land around the main house from being turned into an amusement park. Wenzlick and his son took care of the house until the son's death in 1979. White Haven was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979 and became a National Historic Landmark in 1986.

In 1989, White Haven became part of the National Park Service. Today, it is one of more than 400 sites managed by this agency, helping people learn about American history.

See also

- General Grant National Memorial (Grant's Tomb), New York City, New York

- Grant Cottage State Historic Site, on Mount McGregor, Wilton, New York

- Ulysses S. Grant Home, Galena, Illinois

- Grant Boyhood Home, Georgetown, Ohio

- Grant Birthplace, Point Pleasant, Ohio

- Grant's Farm

- History of slavery in Missouri

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Missouri

- National Register of Historic Places listings in St. Louis County, Missouri