Vine training facts for kids

The way grapevines are grown and supported is called vine training systems. This helps farmers manage the plant's leaves and branches, known as the canopy. The goal is to have enough leaves for the plant to make food (photosynthesis) but not so many that they block sunlight from the grapes. Too much shade can stop grapes from ripening properly or cause diseases.

Using specific training systems also helps control how many grapes a vine produces. It can also make it easier to use machines for tasks like trimming the vines, watering, spraying, and harvesting the grapes.

When choosing a training system, farmers think about the weather. Things like how much sun, humidity, and wind there is can change how well a system works. For example, a system that spreads out the leaves might be great for photosynthesis, but it won't protect the grapes from strong winds. In places like Châteauneuf-du-Pape, strong winds can blow grapes right off the vine. So, a more compact, protective training system is better there.

The words trellising, pruning, and vine training are often used to mean the same thing, but they are a bit different.

- A trellis is the actual structure, like stakes, posts, or wires, that the grapevine is attached to. Some vines grow freely without any trellis.

- Pruning means cutting and shaping the vine's main branches, called "cordons" or "arms," usually in winter. This decides how many buds will grow into grape clusters. In some places, like France, rules even say how many buds are allowed. During summer, pruning can also mean removing young shoots or extra grape bunches.

- Vine training uses both trellising and pruning to control the vine's canopy. This affects how many grapes grow and how good they are, because it controls how much air and sunlight the grapes get. This helps them ripen fully and prevents diseases.

Contents

History of Vine Training

People have been training grapevines for thousands of years, as grapes are one of the oldest crops. Ancient Egyptians and Phoenicians learned that different training methods could help vines produce more fruit. When the Greeks settled in southern Italy around 800 BC, they called the land Oenotria, which might mean "land of staked vines." Later, Roman writers in the 1st century AD gave advice on the best vine training for different vineyards.

For a long time, the type of vine training used in an area was simply based on local traditions. In the early 1900s, many of these traditions became official rules, like the French AOC system.

Serious study of vine training systems really took off in the 1960s. This was when many "New World" wine regions (like California, Washington, Australia, and New Zealand) were starting their wine industries. Unlike older regions with centuries of tradition, these new areas did a lot of research. They wanted to understand how different training systems, pruning, and canopy management affected the quality of wine. This research continues today, leading to new training systems that can be adjusted for different wine styles, labor needs, and vineyard climates.

Why We Train Vines

The main reason for training vines is to manage the canopy, especially to control how much shade the grapes get. But there are many other important reasons too. Grapevines are climbing plants that need support because their woody trunks can't hold up all the leaves and grape clusters on their own. Without support, the vine's "arms" (cordons) would fall to the ground.

Farmers want to stop any part of the vine's cordon from touching the ground. This is because the vine might try to grow new roots from that spot. After the phylloxera epidemic in the 1800s (a tiny louse that attacks vine roots), most vines are now grafted. This means the top part of the vine (which produces grapes) is joined to a root system that is resistant to phylloxera. If the top part of the vine touches the ground and grows roots, it could become infected by phylloxera. Also, this new growth would steal water and nutrients from the main vine, making both parts produce lower quality grapes.

Another reason for vine training is to make vineyard work easier and more efficient, especially for machines. If grape clusters are at a consistent height (like waist to chest level), it's easier for workers to harvest them without bending too much. Keeping the grapes at a steady height also makes it simpler to use machines for pruning, spraying, and harvesting.

Too Much Shade for Grapes

Many vine training systems are designed to prevent too much shade on the grapes from the leaves. While some shade is good, especially in very hot places, to protect grapes from too much heat, too much shade can harm grape development. Grapevines need sunlight to grow and make food through photosynthesis. Even if the leaves at the top get plenty of sun, the young buds, grape clusters, and leaves below them will suffer. Too much shade can reduce how well buds form, how many grapes grow, and the size and number of grapes on a cluster.

Grapes benefit from direct sunlight. It helps them ripen better and develop important flavors and colors. Too much shade leads to grapes that don't ripen as well. It can also cause grapes to have higher levels of potassium, malic acid, and pH, while having less sugar, tartaric acid, and color. Besides a lack of sunlight, too much shade also limits air circulation within the vine's canopy. In wet, humid climates, poor air circulation can lead to grape diseases like powdery mildew and grey rot.

Parts of a Grapevine

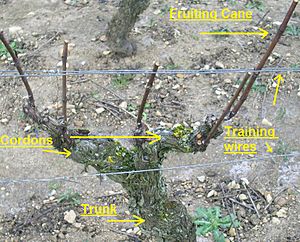

The canopy refers to all the parts of the grapevine that are above ground. This includes the trunk, cordons (main arms), stems, leaves, flowers, and fruit. Vine training mainly focuses on the woody parts: the cordons that grow from the top of the trunk, and the fruiting "canes" that grow from the cordon. When canes are cut back very short, the small stub left is called a "spur."

Grapevines can be either cane trained or spur trained:

- In cane training, there are no permanent cordons. Each winter, the vine is pruned almost entirely back, leaving only one strong cane to become the main branch for the next year's grapes. Examples include Guyot and Pendelbogen.

- In spur training, the main branch or cordon is kept year after year. Only the individual canes growing from it are pruned in winter. Cane-trained vines often have thin, smooth main branches, while spur-trained vines have thick, gnarled cordons. Many old vineyards use spur training. Examples include goblet or bush vine systems.

Cordons can be trained in a unilateral (one arm) or bilateral (two arms) way, with bilateral looking like the letter "T." Cordons are usually trained horizontally along wires. However, some systems, like "V" and "Y" trellises, angle the cordon to look like those letters. Vertical trellising systems, like VSP, refer to the upward direction of the fruiting canes, not the main cordon arms.

From the cordon, new shoots grow from buds. These shoots eventually develop into fruiting canes, where grape clusters will appear. These canes can be positioned at any angle the farmer wants. They are usually pointed upwards, but they can be bent into an arch (like Pendelbogen) or trained to point downwards (like Scott Henry). Training vines to grow downwards often requires more work, as Vitis vinifera vines naturally prefer to grow upwards. In systems like Scott Henry, movable wires allow canes to grow upwards first, then are shifted downwards a few weeks before harvest. The weight of the hanging grapes helps keep the canes pointing down.

The amount of leaves on a grapevine depends on the grape variety and how much it tends to grow. Leaves grow from shoots on the fruiting cane, similar to grape clusters. A vine is called "vigorous" if it produces many shoots, creating a large, leafy canopy. A vine's ability to support a large canopy depends on its healthy root system and stored food. If a vine has too many leaves for its roots, parts of the vine (especially the grapes) might suffer from a lack of resources. While more leaves might seem to mean more food production, this isn't always true. Leaves at the top can create too much shade, stopping photosynthesis in the leaves below. One goal of vine training is to create an "open canopy" that allows enough sunlight to reach all parts of the vine.

Types of Vine Training Systems

Vine training systems can be grouped in different ways. One old way was by the height of the trunk:

- High-trained (or vignes hautes) means the canopy is far from the ground. The ancient Romans used high-trained systems, like the tendone system, where vines grew high overhead on pergolas. A benefit of high-trained systems is better protection from frost.

- Low-trained (or vignes basses) means the canopy is closer to the ground, like the goblet system. Some systems, like Guyot, can be used for both high and low training.

Today, one common way to classify systems is by which parts of the vine are permanent and which are removed each winter during pruning:

- Cane-trained systems: No permanent cordons are kept. The vine is pruned back to a small stub, leaving only one strong cane to grow for the next year. Examples: Guyot and Pendelbogen.

- Spur-trained systems: The main branch or cordon is kept each year, and only individual canes are pruned in winter. Spur-trained vines often have thick, dark, gnarled cordons. Examples: goblet (bush vine) and Cordon de Royat.

Within these groups, systems can be further described by their canopy:

- Is it free (like goblet) or held by wires (like VSP trellising)?

- Does it have a single layer of leaves (Guyot) or a double layer (Lyre)?

- For cordon systems, is it unilateral (one arm) or bilateral (two arms)?

Other ways to classify systems involve trellising:

- Is the vine "staked" with an external support? Some vineyards use permanent stakes to protect against wind. Young vines might use temporary stakes for extra support.

- How many wires are used in the trellis? The number of wires (one, two, three) and whether they can move (like in Scott Henry) affects the canopy size and grape yield.

Common Vine Training Systems

| Training system | Spur or Cane trained | Origins | Where it's found | Benefits | Drawbacks | Notes |

| Alberate | Spur | Likely ancient, used by the Romans | Rural areas of Tuscany and Romagna, Italy | Easy to maintain, needs minimal pruning | Can produce too many grapes of lower quality | Ancient method where vines grow through trees for support |

| Basket Training | Spur | Santorini, Greece | South Australia (like Coonawarra) | Easy to maintain, needs minimal pruning | Lots of shade, which can cause rot and diseases in wet places | A version of the bush vine/Gobelet system with minimal pruning |

| Chablis | Spur | Developed in Chablis | Champagne | Helps vines space themselves out; spurs fan out until they meet the next vine | Arms can fall to the ground if not supported by wires | 90% of Chardonnay vines in Champagne use this method |

| Cordon de Royat | Spur | Bordeaux | Champagne for Pinot noir & Pinot Meunier | A spur-trained version of Guyot Simple; also has a double spur type | ||

| Cordon Trained | Spur | Late 20th century | California and parts of Europe | A spur-trained version of the Guyot system, using single or double cordons instead of canes | ||

| Geneva Double Curtain | Spur | Developed by Nelson Shaulis in New York State in the 1960s | Found worldwide | Increases protection from frost; good for fully mechanized vineyards | Can produce too many grapes | A system where the canopy grows downwards and is split |

| Gobelet | Spur | Likely ancient, used by Egyptians and Romans | Mediterranean regions (e.g., Beaujolais, Languedoc, Sicily) | Good for vines that don't grow very strongly | Vines can be supported by stakes or grow freely | |

| Guyot | Cane | Developed by Jules Guyot in the 1860s | Found worldwide, especially Burgundy | One of the simpler systems, easy to maintain, helps control grape yield | Has a double and simple version | |

| Lenz Moser | Spur | Developed by Dr. Lenz Moser III in Austria in the 1920s | Parts of Europe from mid to late 20th century | Easy to maintain, lower labor and machine costs | Can cause too much shade in the grape area, reducing grape quality | Influenced the development of the Geneva Double Curtain |

| Lyre | Spur | Developed by Alain Carbonneau in Bordeaux | More common in New World wine regions | Allows good air circulation and sunlight into the canopy | Not ideal for vines that don't grow strongly | Can be adapted for cane training |

| Mosel arch | Cane | Mosel | Germany | Each vine has its own stake with two canes bent into a heart shape. Looks like small trees. | ||

| Pendelbogen | Cane | Germany | Switzerland, Rhineland, Alsace, Macon, British Columbia, Oregon | Helps sap flow better and produces more fruit-bearing shoots | Can produce too many grapes and reduce how well they ripen | A version of the Guyot Double |

| Scott Henry | Cane and Spur variant | Developed at Henry Estate Winery in Oregon | Oregon, many New World wine regions | More fruiting areas; split canopy allows more sun, leading to less "grassy" wines with smoother flavors | Can produce too many grapes. Very labor-intensive and costly to set up | Shoots grow along movable wires, allowing half the canopy to be shifted downwards |

| Smart-Dyson | Spur | Developed by Richard Smart (Australia) and John Dyson (America) | United States, Australia, Chile, Argentina, Spain, Portugal | Often used in organic viticulture because the open canopy reduces disease risk and need for sprays | Similar to Scott Henry, but cordons have alternating upward and downward spurs, creating two canopies | |

| Sylvos | Cane | Developed by Carlos Sylvos | Veneto, Australia, New Zealand | Easy to maintain and use machines with | Needs a lot of time for pruning and tying canes | Vines grow downwards from a tall trunk (usually over 1.4 meters) |

| Tendone | Spur | Italy | Southern Italy, parts of South America, Portugal | Grapes grown overhead on arbors or pergolas are less likely to fall or be eaten by animals | Expensive to build and maintain; very dense canopy can lead to diseases | Often used for table grapes rather than wine grapes |

| VSP Trellis | Cane and Spur variant | Several variants developed in Europe and New World wine regions | Cane in New Zealand; spur-trained in France and Germany | Good for mechanized vineyards and vines that don't grow strongly | Can produce too many grapes and cause shading | Most common training system in New Zealand |

See also

In Spanish: Poda de la vid para niños

In Spanish: Poda de la vid para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |