Ancient Rome and wine facts for kids

Ancient Rome played a huge part in the story of wine! The first ideas about growing grapes and making wine in Italy came from the ancient Greeks and the Etruscans. As the Roman Empire grew, so did their skills in making wine. They developed new ways to grow grapes and produce wine, and these methods spread all over their empire. Rome's influence is still seen today in major wine-making countries like France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain.

The Romans believed that wine was something everyone needed every day. This made wine available to almost everyone, from slaves and farmers to rich leaders, and both men and women. To make sure Roman soldiers and settlers always had wine, grape growing and wine production spread to every part of the empire. Trading wine also brought money, attracting merchants to do business with tribes in places like Gaul (modern France) and Germania (modern Germany). This spread Roman ideas even before the Roman army arrived! We often find proof of this ancient wine trade through amphorae – special clay jars used to store and carry wine and other goods.

Writings from famous Roman authors like Cato, Columella, Pliny, and Virgil tell us a lot about how wine was used in Roman culture. They also explain how wine was made and grapes were grown back then. Many of the techniques and ideas first developed by the ancient Romans are still used in winemaking today!

Contents

How Wine Making Started in Rome

The exact start of growing grapes and making wine in Italy is not fully known. It's possible that the Mycenaean Greeks had some influence through early settlements in southern Italy. But the clearest evidence of Greek influence dates back to 800 BC. Before this, grape growing was already common in the Etruscan civilization, which was located around what is now the Tuscany wine region.

The ancient Greeks saw wine as a daily essential and a valuable item for trade. Their colonies were encouraged to plant vineyards to make wine for themselves and to trade with Greek city-states. Southern Italy had many native grapevines, which was perfect for wine production. This led the Greeks to call the region Oenotria, meaning "land of vines." The Greek colonies in the south likely also brought their own ways of pressing wine, which influenced Italian methods.

During the time of the Roman Republic, Roman winemaking was shaped by the skills and techniques of their allies and the regions they conquered. The Greek settlements in southern Italy came under Roman control by 270 BC. The Etruscans, who had long-standing trade routes by sea into Gaul, became largely Roman by the 1st century BC.

The Punic Wars against Carthage had a big impact on Roman grape growing. The Carthaginians had advanced ways of growing grapes, described by their writer Mago. Rome burned Carthage's libraries, but Mago's 26 books on agriculture survived. They were translated into Latin and Greek in 146 BC. Although Mago's original work is lost, Roman writers like Pliny and Columella quoted him a lot.

Rome's Golden Age of Wine

For most of Rome's history, Greek wine was considered the best, and Roman wine was cheaper. But the 2nd century BC brought a "golden age" for Roman winemaking. This was when special vineyards, like early "first growths" (the very best vineyards), started to appear in Rome. The famous wine harvest of 121 BC was known as the Opimian vintage, named after the Roman consul Lucius Opimius. This year was special because it had a huge harvest and produced unusually high-quality wine. Some of the best wines from this vintage were still being enjoyed over a century later!

Pliny the Elder wrote a lot about Rome's top vineyards. The most famous were Falernian, Alban, and Caecuban wines. Other important vineyards were Rhaeticum and Hadrianum, located in what are now the Lombardy and Venice regions. Around Rome itself were estates like Alban and Setinum. South towards Naples were estates such as Caecuban and Falernian. In Sicily, the Mamertinum estate was also highly regarded.

At this peak in the empire's wine history, it's estimated that Rome drank over 180 million liters (47 million US gallons) of wine every year. That's about a bottle of wine each day for every citizen!

Pompeii: A Wine City

One of the most important wine centers in the Roman world was the city of Pompeii. It was located south of Naples, on the coast of Campania. Many farms and vineyards covered the slopes of nearby Vesuvius. The soil there was incredibly fertile, producing some of the best wines for Italy, Rome, and the Roman provinces.

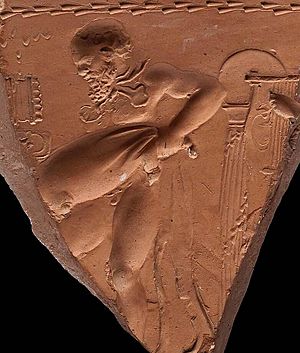

The worship of Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, was very popular in Pompeii. You can see images of him on frescoes (wall paintings) and other ancient objects found in the area. Amphorae with the stamps of Pompeian merchants have been found across the Roman Empire, including in places like Bordeaux and Spain. Some evidence suggests that people even made fake stamps for non-Pompeian wine. This shows how popular Pompeii's wine was, and it might be an early example of wine fraud!

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD had a terrible effect on Campania's wine trade. Ports, vineyards, and warehouses filled with the 78 AD wine harvest were all destroyed. Wine prices shot up, making it too expensive for most people. This happened at a time when even ordinary Romans had started drinking wine regularly. The wine shortage, and the chance to make more money, led to new vineyards being quickly planted closer to Rome. Existing grain fields were even replanted with grapevines.

This rush to plant new vineyards created a wine surplus later on, which caused prices to drop. This hurt wine producers and traders. Also, losing grain fields led to a food shortage for Rome's growing population. In 92 AD, Roman emperor Domitian issued a rule that not only banned new vineyards in Rome but also ordered half the vineyards in Roman provinces to be pulled up.

Even though this rule was mostly ignored in the Roman provinces, historians still debate its effect on the young wine industries in Spain and Gaul. The idea behind the rule was to have just enough wine for Rome's own use, with little left for trade. While vineyards were already growing in these areas, ignoring trade might have slowed down the spread of grape growing and winemaking there. Domitian's rule stayed in place for nearly 200 years until Emperor Probus canceled it in 280 AD.

The destruction and amazing preservation of Pompeii have given us special insights into ancient Roman winemaking. Preserved vine roots show how grapes were planted, and whole vineyards have been found inside the city walls. This helps us understand the pressing and production methods used. Some of these vineyards have even been replanted today with ancient grape types, and scientists are using "experimental archaeology" to try and recreate Roman wine.

How Roman Wine Spread Across the Empire

One of the lasting impacts of the ancient Roman Empire was how they set up grape growing in lands that would become famous wine regions today. Through trade, military campaigns, and settlements, Romans brought their love for wine and the desire to plant vines. Trade was their first and widest influence. Roman wine merchants were eager to trade with everyone, from the Carthaginians and people of southern Spain to the Celtic tribes in Gaul and Germanic tribes along the Rhine and Danube rivers.

During the Gallic Wars, when Julius Caesar arrived in Cabyllona (modern Chalon-sur-Saône) in 59 BC, he found two Roman wine merchants already doing business with the local tribes. In places like Bordeaux, Mainz, and Trier, where Roman army bases were set up, vineyards were planted to supply local needs and cut down on the cost of importing wine from far away. Roman settlements were also founded by retired soldiers who knew about Roman grape growing from their families. They planted vineyards in their new homes. While Romans might have brought grapevines from Italy and Greece, there's also evidence they grew native vines that could be the ancestors of grapes grown in those areas today.

As the Roman Republic grew into an empire beyond Italy, the wine trade also expanded. At first, Italy sold wine to settlements and provinces around the Mediterranean Sea. But by the end of the 1st century AD, the provinces started producing their own wine and even exporting it back to Rome. The Roman market encouraged these provincial exports, increasing both supply and demand.

Wine in Spain (Hispania)

Rome's victory over Carthage in the Punic Wars brought southern and coastal Spain under its control. But it took until the time of Caesar Augustus for the entire Iberian peninsula to be fully conquered. Roman settlement led to the development of wine regions in northern Spain, including what are now Catalonia, Rioja, and Galicia. It also led to wine production in southern Spain, like the Montilla-Moriles region and the sherry region of Cádiz.

While the Carthaginians and Phoenicians first brought grape growing to Spain, Rome's advanced wine technology and new road networks created new business opportunities. Grapes went from being just a farm crop to an important part of a successful business. Spanish wine was even sold in Bordeaux before that region produced its own. Some historians believe that the balisca vine, common in northern Spain (especially Rioja), was brought from Rioja to plant the first Roman vineyards in Bordeaux.

Spanish wines were often traded in Rome. The poet Martial described a highly valued wine called ceretanum from Ceret (modern-day Jerez de la Frontera). Wine historian Hugh Johnson thinks this wine was an early version of sherry. Spanish wines spread more widely than Italian wines throughout the Roman Empire. Amphorae from Spain have been found in France and Britain. The historian Strabo wrote in his work Geographica that the vineyards of Baetica (southern Spain) were famous for their beauty. The Roman agricultural writer Columella was from Cádiz and was greatly influenced by the region's grape growing.

Wine in Gaul (France)

There is archaeological evidence that the Celts first grew grapevines in Gaul (modern France). Grape pips have been found across France, dating back before the Greeks and Romans. Some examples near Lake Geneva are from 10,000 BC. We don't know exactly how much wine the Celts and Gallic tribes made. But when the Greeks arrived near Marseille in 600 BC, they definitely brought new ways of making wine and growing grapes. The Greeks mostly planted in areas with Mediterranean climates, where olives and fig trees also grew well.

The Romans looked for vineyards on hillsides near rivers and important towns. They knew that cold air flows down hills and collects in valleys, which is bad for grapes. So, they avoided valleys and chose sunny hillsides that could provide enough warmth to ripen grapes, even in northern areas. When the Romans took over Massalia (Marseille) in 125 BC, they moved further inland and westward. They founded the city of Narbonne in 118 BC (in the modern Languedoc region) along the Via Domitia, the first Roman road in Gaul. The Romans set up profitable trade with local Gallic tribes, even though these tribes could have made their own wine. The Gallic tribes paid high prices for Roman wine; a single amphora was worth the price of a slave.

From the Mediterranean coast, the Romans moved further up the Rhone Valley. They went to areas where olives and figs couldn't grow, but where oak trees were still found. From their experience in what is now northeastern Italy, the Romans knew that regions with Quercus ilex (a type of oak) had climates warm enough for grapes to ripen fully. In the 1st century AD, Pliny noted that the settlement of Vienne (near what is now the Côte-Rôtie AOC) produced a resinated wine that sold for high prices in Rome. Wine historian Hanneke Wilson says this Rhone wine was the first truly French wine to become famous around the world.

The first mention of Roman interest in the Bordeaux region was in Strabo's report to Augustus. He noted that there were no vines down the river Tarn towards the Garonne into the region known as Burdigala (Bordeaux). The wine for this seaport came from the "high country" region of Gaillac. The Midi region had many native vines that the Romans grew. Many of these are still used today, including Duras, Fer, and Ondenc. Bordeaux's location on the Gironde estuary made it a perfect seaport to transport wine along the Atlantic Coast and to the British Isles. Bordeaux soon had enough vineyards to make its own wine and export it to Roman soldiers in Britain. In the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder mentioned plantings in Bordeaux, including the Balisca grape (known in Spain) under the name Biturica, after the local Bituriges tribe. Some experts believe that Biturica is an ancestor of the Cabernet Sauvignon grape family.

Further up the Rhone, along the Saône river, the Romans found areas that would become the modern wine regions of Beaujolais and Burgundy. Rome's first allies among the Gallic tribes were the Aedui. Rome supported them by founding the city of Augustodunum (modern Autun) in what is now the Burgundy wine region. While vineyards might have been planted there in the 1st century AD, the first clear proof of wine production comes from an account of Emperor Constantine's visit to the city in 312 AD.

The founding of France's other great wine regions is less clear. The Romans liked planting on hillsides, and archaeological evidence of Gallo-Roman vineyards has been found in the chalk hillsides of Sancerre. In the 4th century, Emperor Julian had a vineyard near Paris on the hill of Montmartre. A 5th-century Roman villa in what is now Épernay shows Roman influence in the Champagne region.

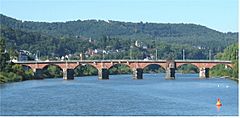

Wine in Germania (Germany)

Even though wild grapevines have grown along the Rhine river since ancient times, the first clear evidence of grape growing dates back to the Roman conquest and settlement of western Germania. Farming tools, like pruning knives, have been found near Roman army posts in Trier and Cologne. But the first definite record of wine production is from a 370 AD work by Ausonius called Mosella. In it, he described lively vineyards along the Mosel river. Ausonius, who was from Bordeaux, compared these vineyards favorably to those in his homeland. He seemed to suggest that grape growing had been in this area for a long time. The Romans planted vineyards in the Rhineland to meet the growing demand from Roman soldiers along the Limes Germanicus (German frontier). It was also very expensive to import wine from Rome, Spain, or Bordeaux. The Romans even thought about building a canal to link the Saône and Mosel rivers to make water trade easier. The alternative was to drink what Tacitus described as an inferior, beer-like drink. Beer was apparently enjoyed by some Roman soldiers. For example, in the Vindolanda tablets (from Vindolanda in Roman Britain, around 97-103 AD), a cavalry officer named Masculus wrote a letter asking for beer to be sent to the garrison because they had run out.

The steep hillsides along the Mosel and Rhine rivers made it possible to grow grapes in a northern location. A slope facing south-southwest gets the most sunshine. The angle of the slope allows the vines to receive the sun's rays directly, rather than at a low or spread-out angle like vineyards on flat land. Hillsides also protected the vines from cold northern winds, and the reflection from the rivers provided extra warmth to help the grapes ripen. With the right type of grape (perhaps an early ancestor of the Riesling grape), the Romans found that wine could be produced in Germania. From the Rhine, German wine would travel downriver to the North Sea and to merchants in Britain, where it started to gain a good reputation.

Despite military conflicts, neighboring Germanic tribes like the Alamanni and Franks were eager customers for German wine. This continued until a 5th-century rule forbade selling wine outside Roman settlements. Wine historian Hugh Johnson believes this might have been an extra reason for the barbarian invasions and sacking of Roman settlements like Trier – "an invitation to break down the door."

Wine in Britannia (Britain)

Rome's influence on Britain regarding wine was more about culture than about growing grapes. Throughout modern history, the British have played a key role in shaping the world of wine and defining global wine markets. Although there's evidence of V. vinifera vines in the British Isles dating back to a warmer climate period, British interest in wine production greatly increased after the Roman conquest of Britain in the 1st century AD.

Amphorae from Italy show that wine was regularly shipped to Britain at great cost, traveling around the Iberian Peninsula. When wine-producing regions developed in Bordeaux and Germany, it became much easier and cheaper to supply the Roman settlers in Britain. However, in Britain itself, no clear evidence of an early local wine industry has been found. This might be because the climate and soil conditions didn't help preserve such evidence. Remnants of amphora production at Brockley Hill, in Middlesex, have been dated to 70-100 AD. This might suggest a very short-lived local wine production, which ended due to Domitian's rule against vine cultivation during a widespread grain shortage. This rule was canceled by Probus in 270 AD. Studies of the Nene Valley and pollen analysis confirm several grape-growing sites, at least from that later date.

More than 400 objects showing Bacchus have been found throughout Britain. This proves how widespread his worship was as a wine-god.

Roman Wine Makers and Sellers

Roman views on wine were complex, especially among the rich equestrian and senator classes. The latter were not supposed to be interested in making personal profits. Rich business people often worked as agents for senatorial landowners. These landowners traditionally used their estates to grow grain, olives, and other basic foods, not for luxury items like wine. Growing grapes required very different skills, practices, and landscapes than traditional farming. It also involved a lot of expense at harvest time for picking, pressing, and storage. The amount of wine produced was also very unpredictable. For a large estate, a bad season could mean huge losses, or profits could be more than what was considered proper for an aristocratic farmer. So, very large wine estates were quite rare. The safest way to invest was to buy small, specialized properties that were already producing wine, along with their equipment, knowledge, and skills. Considering how alcohol can affect people, any investment in large-scale wine production by Rome's ruling class was also seen as morally questionable. Some historians suggest that because of these reasons, Rome's upper classes focused on making refined, high-quality wine and were only slightly involved in high-volume wine production and trade until the Imperial era.

Roman Writers on Wine

The works of classical Roman writers – especially Cato, Columella, Pliny, and Virgil – give us a lot of information about wine's role in Roman culture and how wine was made and grapes were grown back then. Some of these important techniques are still used in modern winemaking. These include thinking about the climate and land when deciding which grape varieties to plant. They also discussed the benefits of different trellising and vine-training systems, and how pruning and harvest yields affect wine quality. Winemaking techniques like sur lie aging (leaving wine on its dead yeast cells after fermentation) and keeping things clean during winemaking to avoid problems were also mentioned.

Marcus Porcius Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato was a Roman statesman. He grew up on his family's farm and wrote a lot about many subjects in De agri cultura (Concerning the Cultivation of the Land). This is the oldest surviving work of Latin prose. He wrote in detail about growing grapes and making wine. He believed that grapes make the best wine when they get the most sunshine. So, he suggested training vines high up in trees and removing all leaves once the grapes started to ripen. He advised winemakers to wait until grapes were fully ripe before harvesting to ensure high quality and protect the estate's reputation. Lower quality and sour wines should be given to the workers. Cato also said that growing vineyards was the only profitable way to use slaves in farming. If slaves became unproductive, their food should be cut. Once they were worn out, they should be sold.

Cato was an early supporter of cleanliness in winemaking. For example, he recommended wiping wine jars clean twice a day with a new broom each time. He also advised sealing the jars well after fermentation to stop the wine from spoiling and turning into vinegar. He said not to fill the amphorae to the very top, leaving some space for a little oxidation. Cato's guide was very popular and became the standard textbook for Roman winemaking for centuries.

Columella

Columella was a writer from the 1st century AD. His 12-volume work De re rustica is considered one of the most important books on Roman agriculture. Volumes 3 and 4 go into the technical details of grape growing, including advice on which soil types produce the best wine. Volume 12 covers various aspects of winemaking.

Columella described boiling grape must (freshly crushed grape juice) in a lead pot to make the sugars more concentrated. This process also allowed the lead to add sweetness and a nice texture to the wine. This practice might have contributed to lead poisoning. He gave precise details on how a well-run vineyard should operate, from the best breakfast for slaves to the amount of grapes expected from each jugerum of land. He also described pruning methods to ensure good harvests. Many modern ways of training vines are similar to Columella's descriptions. In his perfect vineyard, vines were planted two paces apart and tied with willow branches to chestnut stakes about a man's height. He also described some wines from Roman provinces, noting the potential of wines from Spain and the Bordeaux region. Columella praised the quality of wines made from the ancient grape varieties Balisca and Biturica, which experts believe are ancestors of the Cabernet grape family.

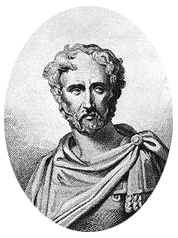

Pliny the Elder

Pliny the Elder was a naturalist and author from the 1st century AD. He wrote the 37-volume Roman encyclopedia Naturalis Historia (Natural History), which he dedicated to Emperor Titus. This work was published after Pliny's death near Pompeii following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The book covers a huge range of topics, including serious discussions about grape growing and wine.

Book 14 is all about wine itself, including a ranking of Rome's "first growths" (best vineyards). Book 17 discusses different grape-growing techniques and an early idea of terroir. This is the idea that unique places produce unique wine. In his rankings of the best Roman wines, Pliny concluded that the vineyard itself had more influence on the wine's quality than the specific vine. The early parts of Book 23 discuss some of the supposed medicinal benefits of wine.

Pliny strongly supported training vines up trees in a pergola (a shaded walkway). He noted that the best wines in Campania all came from this practice. However, because it was dangerous to work on and prune vines trained this way, he advised not using slaves, who were expensive to buy and keep. Instead, he suggested hiring vineyard workers with a contract that covered serious injuries and funeral expenses. He described some grape varieties of his time, recommending Aminean and Nomentan as the best. Some modern experts believe that two white wine varieties he mentioned, Arcelaca and Argitis, might be early ancestors of the modern Riesling grape.

Pliny is also the source of one of the most famous Latin sayings about wine: "In vino veritas," or "There's truth in wine." This refers to how people often talk too much and reveal secrets when they've had too much wine. Pliny didn't see this as a good thing. He regretted that the "excessive candour" of drunkards could lead to bad manners and thoughtless sharing of private matters.

Other Roman Writers

Marcus Terentius Varro, whom the speaker Quintilian called "the most learned man among the Romans," wrote a lot about grammar, geography, religion, law, and science. Only his farming book De re rustica has survived completely. While he borrowed some material from Cato, Varro also credited the lost books of Mago the Carthaginian, as well as Greek writers like Aristotle. Varro's book is written as a dialogue (a conversation) and has three parts. The first part contains most of the discussion on wine and grape growing. He defined old wine as one that was at least a year old. However, he noted that while some wines are best drunk young, especially fine wines like Falernian were meant to be drunk much older.

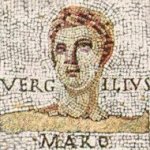

The poetry of Virgil is similar to that of the Greek poet Hesiod. It focuses on the moral values and good qualities of grape growing, especially the hard work and honesty of Roman farmers. The second book of his teaching poem Georgics deals with grape growing. Virgil advised leaving some grapes on the vine until late November, when they become "stiff with frost." This early version of ice wine would have produced sweet wines without the sourness of wine made from grapes harvested earlier.

Virgil's friend Horace often wrote about wine, though no single work is entirely about it. He believed in an Epicurean view of enjoying life's pleasures, including wine, in moderation. Among the earliest recorded examples of choosing a wine for a specific event, Horace's Odes included serving a wine from the guest's birth year at a celebration. He wrote about serving simple wines for everyday use and saving famous wines like Caecuban for special occasions. Horace enthusiastically sided with those who believed wine, not water, was the preferred drink for poetic inspiration. He loved wine so much that when he thought about dying, he was more afraid of leaving his beloved wine cellar than his wife.

Palladius was a 4th-century writer who wrote the 15-volume farming book Opus agriculturae. The first volume was an introduction to basic farming. The next 12 volumes were dedicated to each month of the year and the specific farming tasks to be done in that month. While Palladius covered many crops, he wrote more about vineyard practices than any other. The last two volumes mostly dealt with veterinary medicine for farm animals but also included a detailed account of late-Roman grafting practices. Although he borrowed heavily from Cato, Varro, Pliny, and Columella, Palladius's work is one of the few Roman farming accounts that was still widely used through the Middle Ages and into the early Renaissance. His writings on grape growing were often quoted by later scholars.

How Romans Made Wine

The process of making wine in ancient Rome started right after the harvest. Grapes were often crushed by foot, similar to the French pigeage. The juice that came out first was the most valued and kept separate from what would come later from pressing the grapes. This free-run juice was also thought to have the best medicinal benefits.

Cato described the pressing process taking place in a special room. This room had a raised concrete platform with a shallow basin that had raised edges. The basin sloped gently towards a runoff point. Long, wooden beams were placed horizontally across the basin. The front parts of these beams were attached by rope to a windlass (a machine for winding ropes). The crushed grapes were placed between the beams, and pressure was applied by winding down the windlass. The pressed juice flowed down between the beams and collected in the basin. Building and using a wine press was hard work and expensive, so it was usually only used on large estates. Smaller wineries relied only on treading to get grape juice.

If a wine press was used, an estate would press the grape skins one to three times. Juice from later pressings would be rougher and more tannic. The third pressing usually made a low-quality wine called lora. After pressing, the grape must (juice with skins) was stored in large earthenware jars called dolia. These jars could hold thousands of liters and were often partly buried in the floors of a barn or warehouse. Fermentation took place in the dolium, lasting from two weeks to a month. After that, the wine was moved and put into amphorae for storage. Small holes drilled into the top allowed the carbon dioxide gas to escape.

To make white wine taste better, it might be aged on its lees (dead yeast cells). Sometimes chalk or marble dust was added to reduce acidity. Wines were often exposed to high temperatures and "baked," a process similar to how modern Madeira is made. To make a wine sweeter, a part of the grape must was boiled to concentrate the sugars. This process was called defrutum and was then added to the rest of the fermenting batch. (Columella's writings suggest that Romans believed boiling the must also helped preserve it.) Lead was also sometimes used as a sweetener, or honey could be added. As much as 3 kilograms (6.6 pounds) of honey were recommended to sweeten 12 liters (3.2 US gallons) of wine to Roman tastes. Another technique was to keep some of the sweeter, unfermented must and blend it with the finished wine. Today, this method is known as süssreserve.

Roman Wine Types

Like in much of the ancient world, sweet white wine was the most highly valued style. Wine was often mixed with warm water, and sometimes even seawater.

The ability to age well was a desired quality in Roman wines. Older wines from past harvests sold for higher prices than wines from the current year, no matter their overall quality. Roman law defined "old" wine as wine that had aged for at least a year. Falernian wine was especially valued for its aging ability. It was said to need at least 10 years to mature, but was at its best between 15 and 20 years. The white wine from Surrentine was said to need at least 25 years to be ready.

Similar to Greek wine, Roman wine was often flavored with herbs and spices (like modern vermouth or mulled wine). It was sometimes stored in containers coated with resin, giving it a taste similar to modern retsina. Romans were very interested in the aroma of wine and tried different ways to make a wine smell better. One technique used in southern Gaul was planting herbs like lavender and thyme in the vineyards. They believed the flavors would pass through the soil into the grapes. Modern wines from the Rhone region are often described with aromas of lavender and thyme, likely due to the grape varieties used and the terroir (the unique environment of the vineyard). Another common practice was storing amphorae in a smoke chamber called a fumarium to add a smoky flavor to the wine. Passum, or wine made from dried grapes (raisins), was also very popular. It was produced in the eastern Mediterranean and widely used in religious ceremonies, cooking, and medicine.

The term "vinum" covered a wide range of wine-based drinks. The quality depended on how much pure grape juice was used and how much the wine was diluted when served. Temetum, a strong wine from the first pressing, was used for sacrifices and served undiluted. It was supposedly reserved for elite Roman men and for offerings to the gods. Its name suggests it might have come from the Etruscans. In Rome's distant past, temetum might have been an alcoholic drink made from Rowan fruits. Much lower in quality was posca, a mix of water and sour wine that hadn't yet turned into vinegar. It was less acidic than vinegar but still had some wine aromas and texture. It was the preferred drink for Roman soldiers because of its low alcohol content. Posca's use as soldier's rations was written into Roman law, and each soldier received about a liter per day. Even lower in quality was lora (modern-day piquette). This was made by soaking the pomace (grape skins already pressed twice) in water for a day, and then pressing it a third time. Cato and Varro recommended lora for their slaves. Both posca and lora were the most common wines for ordinary Romans. They were probably mostly red wines, as white wine grapes would have been saved for the upper class.

Grape Varieties in Ancient Rome

The writings of Virgil, Pliny, and Columella give us the most details about the grape varieties used to make wine in the Roman Empire. Many of these grapes have been lost to history. While Virgil's writings often don't separate a wine's name from the grape variety, he frequently mentioned the Aminean grape. Pliny and Columella ranked it as the best in the empire. Pliny described five sub-varieties of this grape that produced similar but distinct wines, saying it was native to Italy. While he claimed that only Democritus knew every grape variety, he tried to speak with authority on the grapes he thought were the only ones worth considering.

Pliny described Nomentan as the second-best wine-producing grape, followed by Apian and its two sub-varieties, which were the preferred grape of Etruria. The only other grapes he considered worthy were Greek varieties, including the Graecula grape used to make Chian wine. He noted that the Eugenia grape had promise, but only if planted in the Colli Albani region. Columella mentioned many of the same grapes but noted that the same grape produced different wines in different regions and could even be known by different names, making it hard to track. He encouraged grape growers to experiment with different plantings to find the best for their areas.

Experts who study grape varieties (ampelographers) debate these descriptions and their possible modern relatives. The Allobrogica grape, used to make the Rhone wine of Vienne, may have been an early ancestor of the Pinot family. Other theories suggest it was more closely related to Syrah or Mondeuse noire. The Rhaetic grape that Virgil praised is believed to be related to the modern Refosco grape of northeastern Italy.

Wine in Roman Culture

In its early years, Rome probably imported wine as a somewhat rare and expensive item. Their native wine-god, Liber pater, was likely a minor deity. Rome's traditional history says its first king, Romulus, offered the gods milk, not wine. The writer Aulus Gellius claimed that in those early times, women were forbidden to drink wine.

Wine played a major role in ancient Roman religion and Roman funerary practices. It was the preferred offering for most gods, including one's deified ancestors. Tombs were sometimes fitted with a permanent, usually stoppered "feeding tube" for these offerings. The invention of wine was usually credited to Liber or his Greek equivalents, Bacchus (later Romanized) and Dionysus. Ordinary, everyday, mixed wines were protected by Venus, but were considered common (vinum spurcum). Therefore, they could not be used in official sacrifices to Roman state gods. A sample of pure, undiluted strong wine from the first pressing was offered to Liber/Bacchus, in thanks for his help in its production. The undiluted wine, known as temetum, was usually reserved for Roman men and Roman gods, especially Jupiter, king of the gods. It was an essential part of the secret, night-time, and women-only Bona Dea festival. During this festival, it was freely consumed but politely referred to as "milk" or "honey." Outside of this context, ordinary wine (Venus' wine) flavored with myrtle oil was thought especially suitable for women; myrtle was sacred to Venus.

The two main public festivals about wine production were the Vinalia. At the Vinalia prima ("first Vinalia") on April 23, ordinary men and women tasted the previous year's wine in Venus's name. Meanwhile, the Roman elite offered a generous wine offering to Jupiter, hoping for good weather for the next year's harvest. The Vinalia Rustica on August 19, originally a country harvest festival, celebrated the grape harvest and the growth of all garden crops. Its patron god may have been Venus, or Jupiter, or both.

Early Roman culture was strongly influenced by the neighboring Etruscans to the north and the ancient Greek colonists of Southern Italy (Magna Graecia). Both of these cultures exported wine and highly valued grape growing. Although Rome was still quite "dry" compared to Greek standards, Roman attitudes towards wine changed greatly as the empire grew. Wine had religious, medicinal, and social roles that made it different from other parts of Roman cuisine. Wine might be watered down by more than half its volume, possibly for taste or purification. Drinking too much undiluted wine was seen as uncivilized and foolish. On the other hand, undiluted wine was thought to be good and "warming" for old men. Throughout Rome's Republic and Imperial eras, offering good wine to guests at banquets showed the host's generosity, wealth, and status.

During the mid-to-later Republic, wine was increasingly seen as a daily necessity rather than just a luxury for the rich. Cato recommended that slaves should have a weekly ration of 5 liters (over a gallon), though this should be sour or lower-quality wine. If slaves became old, sick, or unproductive, Cato advised cutting their rations in half. The widespread planting of grapevines shows the increased demand for wine among all social classes. The growing market for wine also reflects a general change in Roman diets. In the 2nd century BC, Romans began to shift from meals of moist porridge to more bread-based meals; wine helped with eating the drier food.

Bacchus Worship

The Bacchanalia were private Roman mystery cults dedicated to Bacchus, the Greco-Roman god of wine and freedom. They were based on the Greek Dionysia and likely arrived in Rome around 200 BC from Greek colonies in southern Italy and Etruria. They were originally occasional, women-only events, but became more popular and frequent. They were then opened to priests and followers of both genders and all social classes. They may have briefly replaced an existing, legal cult to Liber. Followers used music, dance, and lots of wine to achieve ecstatic religious possession. The Roman Senate saw the cult as a threat to its own power and Roman morality. They suppressed it very harshly in 186 BC. Of about seven thousand followers and their leaders, most were put to death. After that, the Bacchanalia continued in a much smaller form, supervised by Rome's religious authorities, and were probably absorbed into Liber's cult. Despite the ban, illegal Bacchanals secretly continued for many years, especially in Southern Italy, where they likely originated.

Wine in Judaism and Christianity

As Rome took in more cultures, it met people from two religions that generally viewed wine positively: Judaism and Christianity. Grapes and wine appear often, both literally and symbolically, in both the Hebrew and Christian Bibles. In the Torah, grapevines were among the first crops planted after the Great Flood. When exploring Canaan after the the Exodus from Egypt, one good report about the land was that grapevines were plentiful. Jews under Roman rule accepted wine as part of their daily life, but they disliked the excesses they linked with Roman "impurities."

Many Jewish views on wine were adopted by the new Christian group that appeared in the 1st century AD. One of the first miracles performed by the group's founder, Jesus, was turning water into wine. Also, the sacrament of the Eucharist prominently involved wine. The Romans saw some similarities between Bacchus and Christ. Both figures had stories that strongly featured the idea of life after death: Bacchus in the yearly harvest and dormancy of the grape, and Christ in the death and resurrection story. The Eucharist's act of drinking wine as a symbol for consuming Christ, whether spiritually or metaphorically, echoes the rites performed in festivals dedicated to Bacchus.

The influence and importance of wine in Christianity were undeniable. Soon, the Church itself would take over from ancient Rome as the main influence in the world of wine for centuries leading to the Renaissance.

Medical Uses of Wine

Romans believed that wine had the power to both heal and harm. Wine was a recommended cure for mental problems like depression, memory loss, and grief. It was also used for physical problems, from bloating, constipation, diarrhea, gout, and halitosis to snakebites, tapeworms, urinary problems, and vertigo.

Cato wrote a lot about the medical uses of wine. This included a recipe for a laxative: wine made from grapevines treated with a mix of ashes, manure, and hellebore. He recommended soaking the flowers of certain plants, like juniper and myrtle, in wine to help with snakebites and gout. He also believed that a mixture of old wine and juniper, boiled in a lead pot, could help with urinary issues. Mixing wine with very acidic pomegranates could cure tapeworms.

The 2nd-century CE Greco-Roman physician Galen provided several details about wine's medicinal use in later Roman times. In Pergamon, Galen was responsible for the diet and care of the gladiators. He used wine freely in his practice, proudly saying that not a single gladiator died under his care. Wine served as an antiseptic for wounds and a pain reliever for surgery. When he became Emperor Marcus Aurelius's physician, he developed special medicines made from wine called theriacs. Superstitious beliefs about theriacs' "miraculous" ability to protect against poisons and cure everything from the plague to mouth sores lasted until the 18th century. In his work De Antidotis, Galen noted that Romans' tastes were changing from thick, sweet wines to lighter, dry wines that were easier to digest.

The Romans were also aware of the negative health effects of drinking wine, especially the tendency towards "madness" if consumed too much. Lucretius warned that wine could make one furious and lead to arguments. Seneca the Elder believed that drinking too much wine made a person's physical and psychological flaws worse. Drinking wine in excess was frowned upon, and those who drank heavily were considered dangerous to society. The Roman politician Cicero often called his rivals drunkards and a danger to Rome. Most notably, Mark Antony apparently once drank so much that he vomited in the Senate.

See also

In Spanish: Vino en la Antigua Roma para niños

In Spanish: Vino en la Antigua Roma para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |