Ancient Greece and wine facts for kids

| This article contains special characters. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols. |

Wine was very important in ancient Greece. It helped the Greeks trade with other countries and regions. Many customs and parts of their culture were connected to wine. It also brought big changes to their society.

One famous saying explains how important wine was:

People living around the Mediterranean Sea started to become more civilized when they learned to grow olive trees and grapevines.

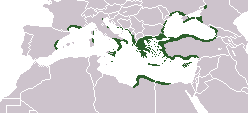

The ancient Greeks were pioneers in growing grapes (this is called viticulture) and making wine. They shared their new methods with early winemaking communities in places like modern-day France, Italy, Austria, and Russia. They did this through trade and by setting up new colonies. Because of this, they greatly influenced other ancient European wine cultures, including the Celts, Etruscans, Scythians, and eventually the Romans.

Contents

How Wine Began in Ancient Greece

Growing grapes has been a part of Greece since the late Neolithic period (the New Stone Age). By the early Bronze Age, growing grapes for wine was common. Through trade with ancient Egypt, the Minoan civilization on the island of Crete learned about Egyptian winemaking. This knowledge likely then spread to Mycenaean Greece.

Minoan palaces had their own vineyards. For example, a place dedicated to wine production was found at Kato Zakros in 1961. In Minoan culture around 1500 BC, wine and the sacred bull were linked. They used horn-shaped drinking cups called rhyta. Grapes, along with olives and grain, were a very important farm crop. They were essential for food and for communities to grow. The ancient Greek calendar even followed the cycle of the grape-growing year.

One of the oldest known wine presses was found in Palekastro in Crete. It's believed that the Mycenaeans spread grape growing from Crete to other islands in the Aegean Sea and possibly to mainland Greece.

During the Mycenaean period, wine became even more important culturally, religiously, and economically. Ancient records on tablets show details about wine, vineyards, and wine merchants. They also mention Dionysus, the Greek god of wine. The Greeks even included the story of how winemaking began in the myths of Dionysus and the hero Aristaeus.

Early pieces of amphoras (large storage jars) show that the Mycenaeans actively traded wine across the ancient world. They traded with places like Cyprus, Egypt, Palestine, Sicily, and southern Italy.

Greek Colonies and Wine Trade

As Greek city-states set up colonies around the Mediterranean Sea, the settlers brought grapevines with them. They also started growing the wild grapevines they found. Sicily and southern Italy were some of the first places they colonized because these areas already had many grapevines. The Greeks called the southern part of the Italian Peninsula Oenotria, which means "land of vines."

Settlements in Massalia (in southern France) and along the Black Sea followed. The Greeks hoped that wine made in these colonies would not only meet their own needs but also create trading chances to supply the nearby city-states.

Athens itself was a big and profitable market for wine. Large vineyards grew in the Attica region and on the island of Thasos to help meet this demand. Some historians think the Greeks might have brought grape growing to Spain and Portugal. However, others believe the Phoenicians probably got there first.

Greek coins from ancient times often show grape clusters, vines, and wine cups. This shows how important wine was to the ancient Greek economy. With every major trading partner, from the Crimea, Egypt, Scythia, Etruria, and beyond, the Greeks shared their knowledge of grape growing and winemaking. They also traded the wine they produced. Millions of amphora pieces have been found by archaeologists. These jars have unique seals from different city-states and Aegean islands, showing how far Greek influence reached.

A shipwreck found off the coast of southern France contained almost 10,000 amphoras. These jars held nearly 300,000 liters of Greek wine. This wine was likely meant for trade up the Rhône and Saône rivers into Gaul (ancient France). It's estimated that the Greeks shipped about 10 million liters of wine into Gaul each year through Massalia. In 1929, the Vix Grave was discovered in Burgundy. It contained several items that showed strong connections between Greek wine traders and local Celtic villagers. The most famous item was a large Greek-made krater, a mixing bowl designed to hold over 1,000 liters of wine.

How Greeks Grew Grapes and Made Wine

Ancient Greeks called the cultivated grapevine hemeris, meaning "tame," to tell it apart from wild vines.

The Greek writer Theophrastus, who lived in the 4th century BC, wrote detailed records about Greek ideas and new methods in grape growing. One of these was studying different vineyard soils and matching them correctly to specific grapevines. Another new idea was to grow fewer grapes on each vine. This made the grapes have more intense flavors and better quality, rather than just producing a lot of grapes. At that time, it was very unusual to intentionally limit how much food was grown.

Theophrastus also described how to use suckering (removing unwanted shoots) and plant cuttings to plant new vineyards. The Greeks also used vine training methods, stacking plants to make them easier to grow and harvest. They didn't just let the grapevines grow wild as bushes or up trees.

While experts haven't found the exact ancestors of today's Vitis vinifera grape varieties among those grown by the ancient Greeks, some grapes have clear Greek origins. Examples include Aglianico (also called Helleniko), Grechetto, and Trebbiano (also called Greco).

Not all Greek grape-growing techniques were widely adopted. Some Greek vineyards used special beliefs to protect against disease and bad weather. For example, they might perform rituals to keep their crops safe.

The Greeks used an early way of crushing grapes called pigeage. Baskets full of grapes were put into wooden or earthenware vats. Vineyard workers would hold onto a rope or plank above for balance and crush the grapes with their feet. Sometimes, they would even play a flute while doing this, making it a festive event. After crushing, the grapes were put into large pithoi (jars) where fermentation (the process that turns grape juice into wine) took place.

Writings by Hesiod and Homer's Odyssey mention some of the earliest ways of making straw wine. This involved laying out freshly harvested grapes on mats to dry almost into raisins before pressing them. A wine made on Lesbos called protropon was one of the first known to be made only from "free run juice." This juice comes from grape clusters that release their liquid just from their own weight.

Other Greek ideas included harvesting grapes that were not fully ripe to make a more acidic wine for blending. They also discovered that boiling grape must (freshly crushed grape juice) was another way to add sweetness to the wine. The Greeks believed wine could also be improved by adding resin, herbs, spices, seawater, brine, oil, and perfume. Modern examples of these practices include Retsina (wine with resin), mulled wine (with spices), and vermouth (with herbs).

Even as late as 691 AD, a rule was made forbidding people from shouting "Dionysus!" while crushing wine grapes. This shows how long the old traditions connected to the god of wine lasted.

Types of Greek Wine

In ancient times, a wine's reputation depended on the region it came from, not on a specific winemaker or vineyard. In the 4th century BC, the most expensive wine sold in Athens came from Chios. It cost between a quarter of a drachma and 2 drachmas for a chous (about 3 liters, or the same as four standard 750 ml wine bottles today).

Like early wine critics, Greek poets would praise good wines and speak less favorably about those that weren't as good. The wines most often mentioned as being high quality came from Chalkidiki, Ismaros, Chios, Kos, Lesbos, Mende, Naxos, Peparethos (today's Skopelos), and Thasos. Two individual wines that were praised, Bibline and Pramnian, had unknown origins. Bibline is thought to have been made in a similar way to Phoenician wine from Byblos. Greek writers like Archestratus highly valued it for its fragrant smell. The Greek version of this wine is believed to have come from Thrace from a grape variety called Bibline.

Pramnian wine was found in several regions, especially Lesbos, but also Icaria and Smyrna (in modern-day Turkey). It was suggested by Athenaeus that Pramnian was a general name for a dark wine that was good quality and could age well.

The earliest mention of a specific named wine is from the poet Alkman (7th century BC). He praised "Dénthis," a wine from the foothills of Mount Taygetus in Messenia, calling it "anthosmías" ("smelling of flowers"). According to wine expert Jancis Robinson, Limnio was almost certainly the Lemnia grape described by Aristotle as a specialty of the island of Limnos. This is probably the same as the modern-day Lemnió grape variety, a red wine with a scent of oregano and thyme. If so, this makes Lemnió the oldest known grape variety still grown today.

The most common style of wine in ancient Greece was sweet and aromatic, though drier wines were also made. The color ranged from very dark, almost black, to tawny (brownish-orange), to almost clear. It was hard to control oxidation, which is a common problem in wine. This meant many wines didn't stay good for long after they were made. However, wines that were stored well and aged were highly valued. The poet Hermippus said the best aged wines smelled like "violets, roses, and hyacinth." Comedic poets joked that Greek women liked "old wine but young men."

Wine was almost always diluted, usually with water (or snow if they wanted it cold). They believed that drinking undiluted wine could even be deadly. Greeks thought that mixing wine with water was a sign of civilized behavior.

Wine in Greek Culture

Besides being important for trade, wine also played key religious, social, and medical roles in Greek society. The "feast of the new wine" (me-tu-wo ne-wo) was a festival in Mycenaean Greece that celebrated the "month of the new wine." The worship of Dionysus was very active and mysterious. It was even featured in Euripides's play The Bacchae. Several festivals were held throughout the year to honor the God of wine.

In February, the Anthesteria festival marked the opening of wine jars from the previous autumn's harvest. It included wine-drinking contests and a parade through Athens with wine jars. The Dionysia festivals included plays (both comedies and tragedies) in honor of the God of wine.

Wine was often part of the symposium, which was a drinking party. These parties sometimes included the game of kottabos, where people would flick lees (sediment) from a wine cup towards a target.

The Greeks, including Hippocrates, often studied the medicinal uses of wine. Hippocrates did a lot of research on this topic. He used wine to treat fevers, help people recover from illness, and as an antiseptic (to clean wounds). He also studied how wine affected his patients' stool. Greek doctors prescribed different types of wine as a pain reliever, a diuretic (to help the body get rid of water), a tonic (to make you feel stronger), and to help with digestion.

The Greeks also knew about some negative health effects, especially from drinking too much wine. The poet Eubulus noted that three bowls (kylikes) were the perfect amount of wine to drink. The idea of three bowls representing moderation is a common theme in Greek writings. (Today, a standard 750 ml bottle usually holds about three to six glasses of wine, depending on how much you pour.)

See also

In Spanish: Vino en la Antigua Grecia para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |