Winemaking facts for kids

Winemaking is the process of making wine. It starts with choosing the best fruit, usually grapes. Then, the fruit juice goes through a special process called fermentation, which turns its sugars into alcohol. Finally, the wine is put into bottles. People have been making wine for thousands of years! The science behind wine and winemaking is called oenology. A person who makes wine is often called a winemaker or a vintner. Growing grapes is known as viticulture, and there are many different kinds of grapes.

Winemaking can be split into two main types:

- Still wine: This wine has no bubbles.

- Sparkling wine: This wine has bubbles, either naturally formed or added.

Other main types of wine include red wine, white wine, and rosé. While most wine is made from grapes, it can also be made from other fruits, like in fruit wine. There are also similar light alcoholic drinks, such as mead (made from honey and water) and kumis (made from fermented mare's milk).

Contents

- How Wine is Made: The Process

- The Grapes: Starting Point of Wine

- Harvesting and Destemming Grapes

- Crushing and First Fermentation

- Cold Stabilization

- Secondary Fermentation and Aging

- Malolactic Fermentation

- Laboratory Tests

- Blending and Fining

- Preservatives in Wine

- Filtration

- Biodynamic Wines

- Bottling the Wine

- Winemakers

- See also

How Wine is Made: The Process

Making wine involves five main steps, starting with picking the grapes. After picking, the grapes are brought to a winery to get ready for the first stage of fermentation. How red wine and white wine are made starts to be different at this point.

Red wine is made from the pulp (called must) of red or black grapes. The grape skins stay with the juice during fermentation, which gives the wine its red color.

White wine is made by pressing crushed grapes to get just the juice. The skins are removed and are not used further. Sometimes, white wine can even be made from red grapes! This happens by quickly pressing the grapes to get the juice with very little contact with the dark skins.

Rosé wines are made from red grapes. The juice stays in contact with the dark skins just long enough to get a pink color. This is called maceration or saignée. Less often, rosé is made by mixing red and white wine. White and rosé wines do not get much of the tannins (a bitter substance) from the skins.

To begin the first fermentation, winemakers might add yeast to the grape must (for red wine) or juice (for white wine). Sometimes, natural yeast already on the grapes or in the air can start the process. This first fermentation usually takes one to two weeks. During this time, the yeast eats the sugars in the grape juice and turns them into ethanol (alcohol) and carbon dioxide gas. The carbon dioxide then goes into the air.

After the first fermentation of red grapes, the "free run" wine (juice that flows out easily) is pumped into tanks. The remaining grape skins are then pressed to get out any last juice and wine. The pressed wine can be mixed with the free run wine if the winemaker chooses. The wine is kept warm so that any leftover sugars continue to turn into alcohol and carbon dioxide.

The next step for red wine is called malolactic conversion. This is a natural process where special bacteria change "crisp, green apple" malic acid into "soft, creamy" lactic acid. This makes the wine taste smoother. Red wine is sometimes moved into oak barrels to age for weeks or months. This gives the wine special oak flavors and some tannin. Before bottling, the wine needs to be settled or cleared, and any final adjustments are made.

The time from picking grapes to drinking the wine can be a few months for young wines, or over twenty years for wines that are meant to age. However, only about 10% of red wines and 5% of white wines will taste better after five years than they do after just one year.

Depending on the grape quality and the type of wine desired, some of these steps might be combined or skipped. Many good quality wines are made using slightly different methods. The quality mostly depends on the grapes themselves, not just the steps taken during winemaking.

There are also different ways to make certain wines. For sparkling wines like Champagne, a second fermentation happens inside the bottle. This traps carbon dioxide in the wine, creating the famous bubbles. These bottles then spend time on a special rack before being opened to remove any leftover bits. Other sparkling wines, like Prosecco, use a faster method where carbon dioxide is added by machines to create bubbles.

Sweet wines are made by stopping the fermentation before all the sugar has turned into alcohol, leaving some residual sugar. This can be done by chilling the wine, adding certain things to stop the yeast, or filtering out all yeast and bacteria. For very sweet wines, the grapes might be harvested late, frozen (for ice wine), or allowed to dry out to concentrate their sugars. In these high-sugar wines, fermentation often stops naturally because of the high sugar and rising alcohol levels. For port wine and other fortified wines, strong alcohol (like brandy) is added to stop fermentation and set the alcohol content. Sometimes, a winemaker might save some sweet grape juice and add it to the wine after fermentation is done, a method called süssreserve in Germany.

The winemaking process creates some leftover materials like wastewater, pomace (grape skins and seeds), and lees (dead yeast cells). These need to be collected and handled properly.

Some "synthetic" or "fake" wines are made without grapes at all. They start with water and alcohol, then add acids, sugars, and other compounds.

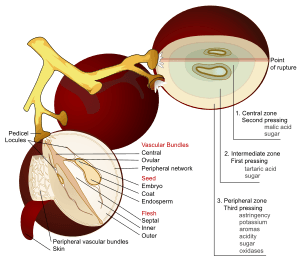

The Grapes: Starting Point of Wine

The quality of the grapes is the most important factor for the quality of the wine. Many things affect grape quality, such as the grape type, the weather during the growing season, minerals in the soil, how acidic the soil is, when the grapes are picked, and how the vines are trimmed. All these factors together are often called the grape's terroir. Because grapes are sensitive to weather, winemaking is affected by climate change.

Grapes are usually picked from the vineyard in the northern hemisphere from early September to early November. In the southern hemisphere, it's from mid-February to early March. In some cooler southern areas, like Tasmania, picking can even go into May.

The most common type of grape used for wine is Vitis vinifera, which includes almost all European grape varieties.

Harvesting and Destemming Grapes

Harvest is when grapes are picked, and it's the very first step in making wine. Grapes can be picked by machines or by hand. The winemaker usually decides when to harvest based on the sugar level (called °Brix), acid level (TA or Titratable Acidity), and pH of the grapes. They also consider how ripe the berries taste, how the tannins are developing (seed color and taste), the overall health of the grapevine, and weather forecasts.

Mechanical harvesters are large machines that drive over grapevine trellises. They use plastic or rubber rods to shake the grapes off the vine. Mechanical harvesters can pick grapes from a large area quickly and with fewer workers. However, a downside is that they can pick up unwanted things like leaves, stems, moldy grapes, or even small animals. Some winemakers clean the vines before mechanical harvesting to avoid this. In the United States, mechanical harvesting is rarely used for very high-quality wines because it can damage grapes and increase oxidation. In other countries, like Australia and New Zealand, it's more common due to fewer available workers.

Manual harvesting means picking grape clusters by hand from the grapevines. In the United States, some grapes are put into large bins (one or two tons) to be taken to the winery. Hand-picking allows skilled workers to choose only ripe clusters and leave behind any that are not ripe or have problems like rot. This is a good way to make sure only good quality fruit goes into the wine.

Destemming is the process of separating the grapes from their stems (the rachis). Depending on how the wine is made, this step might happen before crushing to reduce the amount of tannins and plant-like flavors in the wine. For some very special German wines, grapes are picked one by one, so destemming isn't needed.

Crushing and First Fermentation

Crushing is when grapes are gently squeezed to break their skins and release the juice inside. Destemming is removing the grapes from their stems. In traditional or small-scale winemaking, grapes were sometimes crushed by stepping on them barefoot, or by using small, simple crushers that could also destem. However, larger wineries use mechanical crusher/destemmers.

The decision to destem is different for red and white wine. For white wine, grapes are usually only crushed, and the stems are put into the press with the berries. The stems help the juice flow better when pressing.

For red winemaking, stems are usually removed before fermentation. Stems have a lot of tannin and can give the wine a plant-like smell (like green bell peppers). Sometimes, if the grapes themselves don't have enough tannin, the winemaker might leave some stems in, especially if the stems have turned brown and are ripe.

If a winemaker wants to get more flavor from the skins, they might crush the grapes after destemming. Removing stems first means no stem tannin will be extracted. In these cases, grapes pass between two rollers that squeeze them enough to separate the skin and pulp, but not so much that the skins are torn too much. For some delicate red wines like Pinot noir or Syrah, some or all grapes might be left whole (uncrushed). This helps keep fruity smells through a process called partial carbonic maceration.

Most red wines get their color from the grape skins. So, the juice needs to be in contact with the skins to get that color. Red wines are made by destemming and crushing grapes into a tank, then leaving the skins with the juice during the whole fermentation (this is called maceration). It's possible to make white (colorless) wines from red grapes by pressing the uncrushed fruit very carefully. This limits contact between the juice and skins, like in the making of Blanc de noirs sparkling wine, which comes from the red Pinot noir grape.

Most white wines are processed without destemming or crushing. They go straight from picking bins to the press. This avoids getting any tannin from the skins or seeds and helps the juice flow well. Sometimes, winemakers choose to crush white grapes for a short time (3 to 24 hours) to let the skins touch the juice. This helps get flavor and tannin from the skins and can also increase the pH of the juice, which might be good for very acidic grapes. This was more common in the 1970s but is still done by some winemakers today.

For rosé wines, the fruit is crushed, and the dark skins stay in contact with the juice just long enough to get the desired pink color. Then the must is pressed, and fermentation continues as if making a white wine.

Yeast is usually already present on grapes, often looking like a powdery coating. The first, or alcoholic, fermentation can happen with this natural yeast. However, because natural yeast can give unpredictable results, winemakers often add special cultured yeast to the must. One problem with using wild yeast is that fermentation might not finish, leaving the wine sweet when a dry wine is wanted. Wild yeast can also sometimes produce unpleasant acetic acid (vinegar).

During the first fermentation, yeast cells eat the sugars in the must and multiply, creating carbon dioxide gas and alcohol. The temperature during fermentation affects both the final taste and how fast the fermentation happens. For red wines, the temperature is usually 22 to 25 °C (72 to 77 °F), and for white wines, it's 15 to 18 °C (59 to 64 °F).

For every gram of sugar that is turned into alcohol, about half a gram of alcohol is made. So, to get a 12% alcohol concentration, the must should have about 24% sugars. The sugar percentage is measured using a special tool called a saccharometer. If the grapes don't have enough sugar for the desired alcohol level, sugar can be added (this is called chaptalization). In commercial winemaking, adding sugar is controlled by local rules.

Wines with more than 12% alcohol can be made using yeast that can handle high alcohol levels. Some yeasts can produce 18% alcohol, but extra sugar is needed for such high alcohol content.

During or after the alcoholic fermentation, a second fermentation called malolactic fermentation can happen. In this process, specific types of bacteria change malic acid into the milder lactic acid. Winemakers often start this fermentation by adding the desired bacteria.

Pressing the Grapes

Pressing is when pressure is put on grapes or pomace (grape skins and seeds) to separate the juice or wine from the solid parts. Pressing isn't always necessary; if grapes are crushed, a lot of juice (called free-run juice) comes out right away and can be used for winemaking. This free-run juice is usually of higher quality than pressed juice. Pressed juice can sometimes have more bitter compounds. However, most wineries use presses to get more juice from each ton of grapes, as pressed juice can be 15% to 30% of the total juice.

Presses work by squeezing grape skins or whole grape clusters between two surfaces. Modern presses control how long and how much pressure is applied, usually increasing from 0 to 2.0 Bar. Sometimes winemakers separate the pressed juice into different batches based on the pressure used. As pressure increases, more tannin is extracted from the skins into the juice, which can make the pressed juice too bitter or harsh. Because water and acid are mostly in the grape pulp, and tannins are mostly in the skin and seeds, pressed juice or wine tends to be less acidic and have a higher pH than free-run juice.

Before modern winemaking, most presses were basket presses made of wood and operated by hand. These presses had a wooden cylinder with slats and a movable top plate that was pushed down. The grapes or pomace were loaded into the cylinder, and the plate was lowered until juice flowed out. As the juice flow slowed, the plate was pushed down again. This continued until the winemaker decided the juice quality was too low or all liquid was pressed. Since the early 1990s, modern mechanical basket presses have become popular again among high-end winemakers who want to copy the gentle pressing of old basket presses.

For red wines, the must is pressed after the first fermentation. This separates the skins and other solids from the liquid. For white wine, the liquid is separated from the must before fermentation. For rosé, the skins might stay in contact for a shorter time to give color, and then the must is pressed. After the wine sits or ages for a while, it is separated from dead yeast and any remaining solids (called lees) and moved to a new container for any further fermentation.

Pigeage (Punching Down the Cap)

Pigeage is a French term for managing the grape skins in fermentation tanks. For certain wines, grapes are crushed and poured into open fermentation tanks. Once fermentation starts, the carbon dioxide gas pushes the grape skins to the surface, forming a layer called the "cap." Since the skins are where the tannins come from, this cap needs to be mixed back into the liquid every day. Traditionally, this was done by stomping through the vat.

Cold Stabilization

Cold stabilization is a process used to reduce tartrate crystals in wine. These crystals, also known as "wine diamonds," look like clear sand grains. They form when tartaric acid and potassium combine and can appear as sediment in the wine, though they are harmless. During cold stabilization, after fermentation, the wine's temperature is lowered to near freezing for one to two weeks. This causes the crystals to separate from the wine and stick to the sides of the tank. When the wine is drained, the tartrates are left behind. They can also form in wine bottles stored in very cold conditions.

Secondary Fermentation and Aging

During the secondary fermentation and aging process, which takes three to six months, fermentation continues very slowly. The wine is kept under an airlock to protect it from air, which can cause oxidation. Proteins from the grapes break down, and leftover yeast cells and other tiny particles settle to the bottom. Potassium bitartrate (wine diamonds) will also settle out, especially if the wine is cold stabilized. As a result, the cloudy wine becomes clear. The wine can be moved (called racking) during this process to remove the lees.

Secondary fermentation usually happens in large stainless steel tanks, oak barrels, or glass demijohns (also called carboys), depending on what the winemakers want to achieve. Unoaked wine is fermented in stainless steel or other materials that don't affect the taste. Depending on the desired taste, wine might be fermented mostly in stainless steel and then briefly put in oak, or fully fermented in stainless steel. Oak chips can also be added to non-wooden barrels for a similar effect, often used in less expensive wines.

Amateur winemakers often use glass carboys, which hold about 4.5 to 54 liters (1 to 14 gallons). The type of container used depends on the amount of wine being made, the grapes, and the winemaker's goals.

Malolactic Fermentation

Malolactic fermentation happens when special bacteria change malic acid into lactic acid and carbon dioxide. This can be done on purpose by adding specific bacteria to the aging wine, or it can happen naturally if these bacteria are already present.

Malolactic fermentation can make wine taste better if it has high levels of malic acid. Malic acid, in large amounts, can make wine taste harsh and bitter. Lactic acid, however, is softer and less sour.

Laboratory Tests

Whether wine is aging in tanks or barrels, tests are regularly done in a laboratory to check the wine's condition.

Blending and Fining

Different batches of wine can be mixed before bottling to get the desired taste. The winemaker can fix any problems by blending wines from different grapes or batches made under different conditions. These adjustments can be simple, like changing acid or tannin levels, or more complex, like mixing different grape types or years to create a consistent taste.

Fining agents are used during winemaking to remove tannins, reduce bitterness, and remove tiny particles that could make the wine cloudy. Winemakers choose which fining agents to use, and these can change for different products or even different batches, often depending on the grapes from that year.

Gelatin has been used in winemaking for centuries and is a traditional way to clarify wine. It's also the most common agent to reduce tannin content. Usually, no gelatin remains in the wine because it reacts with wine parts, clarifies the wine, and forms a sediment that is removed by filtering before bottling.

Besides gelatin, other fining agents often come from animal products, such as milk protein (casein), egg whites, bone char, isinglass (from fish bladders), and skim milk powder. Although not common, finely ground eggshell is sometimes used.

Some flavored wines contain honey or egg-yolk extract.

Non-animal-based filtering agents are also often used. These include bentonite (a clay-based filter), diatomaceous earth, cellulose pads, paper filters, and membrane filters (thin plastic films with tiny holes).

Preservatives in Wine

The most common preservative used in winemaking is sulfur dioxide (SO2). It's usually added as liquid sulfur dioxide, or as sodium or potassium metabisulphite. Another useful preservative is potassium sorbate.

Filtration

Filtration in winemaking has two goals: making the wine clear and making it stable against microbes. For clarification, large particles that make the wine look cloudy are removed. For microbial stabilization, tiny organisms that could spoil the wine or cause it to ferment again are removed.

Clarification removes particles larger than about 5–10 micrometers for rough cleaning, or 1–4 micrometers for clearer wine. For microbial stability, the wine needs to be filtered at least to 0.65 micrometers to remove yeast, and 0.45 micrometers to remove bacteria. However, filtering at this level can sometimes make the wine's color lighter and its body thinner. Microbial stabilization doesn't mean the wine is completely sterile; it just means enough yeast and bacteria have been removed to make the wine stable.

Wine can also become clear naturally by putting it in a refrigerator at about 2 °C (35 °F). The wine takes about a month to settle and become clear without needing any chemicals.

Biodynamic Wines

Biodynamic wines are made using special biodynamic methods for growing the grapes and processing them after harvest. Biodynamic winemaking uses organic farming methods, like using compost as fertilizer and avoiding most pesticides. It also uses soil supplements made from specific formulas, follows a planting calendar based on stars, and treats the earth as a "living and receptive" organism.

Bottling the Wine

A final small amount of sulfite is added to help keep the wine fresh and stop any unwanted fermentation in the bottle. Wine bottles are traditionally sealed with a cork. However, other ways to seal bottles, like synthetic corks and screwcaps, are becoming more popular because they are less likely to cause "cork taint" (a bad smell or taste from the cork). The last step is adding a capsule (a cover) to the top of the bottle, which is then heated to create a tight seal.

Winemakers

A winemaker is a person who makes wine. They are usually employed by wineries or wine companies. However, many independent winemakers make wine at home for fun or for small businesses. Also, winemaking is still done in traditional ways by families who make wine for their own use.

Here are the top 15 wine-producing countries by volume (in thousands of hectoliters):

| Country | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48,525 | 42,772 | 45,616 | 52,029 | 44,739 | 50,000 | 50,900 | 42,500 | 48,500 | |

| 44,381 | 50,757 | 41,548 | 42,004 | 46,698 | 47,000 | 45,200 | 36,600 | 46,400 | |

| 35,353 | 33,397 | 31,123 | 45,650 | 41,620 | 37,700 | 39,300 | 32,500 | 40,900 | |

| 20,887 | 19,140 | 21,650 | 23,590 | 22,300 | 21,700 | 23,600 | 23,300 | 23,900 | |

| 16,250 | 15,473 | 11,778 | 14,984 | 15,197 | 13,400 | 9,400 | 11,800 | 14,500 | |

| 11,420 | 11,180 | 12,260 | 12,500 | 12,000 | 11,900 | 13,100 | 13,900 | 12,500 | |

| 9,327 | 9,725 | 10,569 | 10,982 | 11,316 | 11,200 | 10,500 | 10,800 | 9,500 | |

| 13,000 | 13,200 | 13,511 | 11,780 | 11,178 | 11,500 | 11,400 | 11,400 | 10,800 | |

| 8,844 | 10,464 | 12,554 | 12,820 | 10,500 | 12,900 | 10,100 | 9,500 | 12,900 | |

| 6,906 | 9,132 | 9,012 | 8,409 | 9,334 | 8,900 | 9,000 | 7,500 | 9,800 | |

| 7,148 | 5,622 | 6,308 | 6,237 | 6,195 | 7,000 | 6,000 | 6,700 | 5,300 | |

| 3,287 | 4,058 | 3,311 | 5,100 | 3,700 | 3,600 | 3,300 | 4,300 | 5,200 | |

| 6,400 | 6,353 | 6,400 | 5,300 | 4,900 | 5,600 | 5,200 | 4,700 | 4,700 | |

| - | - | - | 2,600 | 2,400 | 2,600 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 3,400 | |

| Rest of the World | 27,847 | 30,906 | 27,194 | 31,000 | 27,100 | 29,800 | 29,900 | 30,900 | 30,700 |

| World | 264,425 | 267,279 | 257,889 | 290,100 | 270,000 | 277,000 | 273,000 | 251,000 | 282,000 |

See also

In Spanish: Producción del vino para niños

In Spanish: Producción del vino para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |