Ripeness in viticulture facts for kids

When we talk about ripeness in grapes for making wine, it means the grapes are fully grown on the vine and ready to be picked. What "ripe" means can change a lot. It depends on the type of wine being made, like bubbly wine, dessert wine, or regular wine. It also depends on what the winemaker thinks is best. Once grapes are picked, their qualities are set. So, choosing the perfect time to harvest is super important for making great wine!

Many things help grapes ripen. As grapes go through a stage called veraison, their sugar levels go up, and their acid levels go down. The balance between sugar (which affects how much alcohol the wine will have) and acids is key for good wine. Winemakers check the grape juice's sugar content (called "must weight"), its total acidity, and its pH level to decide if it's ripe. More recently, winemakers also look for "physiological" ripeness. This means the tannins and other parts that give wine its color, flavor, and aroma of wine are fully developed.

Contents

How Grapes Change as They Ripen

You could say grapes are always ripening during their yearly life cycle. But more specifically, ripening really kicks off during veraison. This usually happens about 40 to 60 days after the grapes first form. Before veraison, grapes are hard, green, and very sour, with lots of malic acid.

During veraison, which can last 30 to 70 days, grapes change a lot. Their sugar, acid, tannin, and mineral levels all shift. The skins of red grapes start to get their color from special compounds called anthocyanins. These replace the green chlorophyll, making the grapes change from green to red or black.

The grapes get their sugar from the grapevine's stored carbohydrates in its roots and trunk. They also get sugar from photosynthesis, which happens in the leaves. Sucrose from photosynthesis moves from the leaves to the grapes. There, it breaks down into glucose and fructose. How fast sugar builds up depends on things like sunny weather and how many grape clusters are on the vine. As sugar goes up, acids go down. This is partly because the sugar dilutes the acids. Also, the plant uses some acids in its breathing process. This drop in acids, plus more potassium, makes the grape juice's pH level go up.

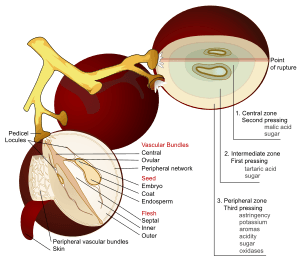

Other parts of the grape also develop during ripening. Minerals like potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sodium increase in the grape skin and pulp. The color changes because of compounds like anthocyanins in the skins. Also, "flavor precursors" start to build up. These are tiny parts that will later give the wine its taste and smell. Tannins in the skin, seeds, and stems also increase. Early on, these tannins are bitter. But as they ripen in the sun, they change. This makes them feel smoother in your mouth when they become wine.

Different Ripeness for Different Wines

What "ripe" means depends on the type of wine. It also depends on what the winemaker believes is the best ripeness. The style of wine is often decided by the balance of sugars and acids. What one winemaker calls "ripe" might be "under-ripe" or "over-ripe" to another! Climate and the grape variety also play a role. In hot places like California or Australia, grapes ripen about 30 days after veraison. In cooler places like the Loire Valley in France, it might take 70 days. Some grapes, like Cabernet Sauvignon, take longer to ripen than others, like Chardonnay or Pinot noir.

Since sugar levels rise as grapes ripen, the sweetness and potential alcohol of the wine are important. This is because yeast turns sugar into alcohol during fermentation. More sugar means more potential alcohol. However, most wine yeasts stop working if the alcohol level gets too high (above 15% alcohol by volume). This leaves some residual sugar, making the wine sweet. Sweet wines, like dessert wines, are often called late harvest wines. They are picked much later than grapes for regular table wines.

Alcohol in wine affects its weight and how it feels in your mouth. It also balances sweetness, tannins, and acids. When you taste wine, alcohol can make acids and tannins feel less harsh. It also helps create different smells in wine as it gets older. Because of this, some winemakers wait for higher sugar levels before harvesting.

For other wines, like Champagne, keeping enough acidity in the grapes is important. Since acid levels drop as grapes ripen, grapes for sparkling wines are often picked very early. These grapes would be too sour for regular table wine. But their high acidity and low sugar are perfect for sparkling wine production.

What Affects When Grapes Ripen

The weather and climate are big factors in grape ripening. Sunlight and warmth are vital for the grapevine to grow and make energy. If there's not enough sun, like during long cloudy periods, the vine slows down. It focuses on surviving, so less energy goes to ripening the grapes. Too much heat can also be bad. Heat waves near harvest can make sugars jump and acids drop fast. Some winemakers might pick early to keep acid levels, even if other parts aren't fully ripe. If acids are too low, winemakers can add them later, like tartaric acid.

Heavy rains before harvest are also a problem. Steady rain can make grapes swell with water, which dilutes their flavors. It can also crack the skins, letting in bad tiny organisms that spoil the wine. Because of these risks, the threat of long rain often leads to an early harvest, even if grapes aren't fully ripe. The best years for wine have slow, steady ripening without extreme heat or too much rain.

How the vineyard is managed also plays a big role. Things like pruning and canopy management affect how the vine grows and uses its energy. Grapevine leaves make energy through photosynthesis. You need enough leaves for the vine to be healthy. But too many leaves can shade the grapes, blocking the sunlight and warmth they need to develop. Too many leaves can also lead to diseases like bunch rot or powdery mildew, which hurt ripening. A vine with too many grape clusters or shoots will have many parts competing for energy. This slows down the ripening of individual clusters. Winemakers try to balance the number of clusters and leaves to get the best ripening.

Sometimes, even with perfect weather and management, not all grapes ripen at the same speed. This problem is called millerandage. It can happen because of bad weather when the grapes are flowering. It can also be caused by soil lacking nutrients like boron, or by grapevine fanleaf virus.

How Winemakers Check Ripeness

Since "ripeness" means many things, winemakers use different ways to check if grapes are ready. The most common way is to measure the sugar, acid, and pH levels. They aim to pick when these numbers are just right for the wine they want to make. Lately, winemakers also look at other things, like how ripe the tannins are and how much flavor has developed. These other factors, beyond just sugar, acid, and pH, are called "physiological" ripeness.

Measuring Sugar Levels

Over 90% of the dissolved stuff in grape juice is sugar. So, measuring the "must weight" is a good way to know how much sugar is in the grapes. Instead of actual weight, they measure the juice's density compared to water. Winemakers use a tool called a refractometer to check the juice from a single grape. Or, they use a hydrometer in the winery with juice from many grapes. Different countries use different scales to measure must weight. For example, the United States uses degrees brix (°Bx), while Germany uses degrees Oechsle (°Oe).

After veraison, winemakers test hundreds of grapes from different parts of the vineyard. They usually pick grapes from the middle of the clusters. They plot the must weight on a chart to see how sugar levels are increasing. The ideal must weight depends on the winemaker's goal. For a wine with 12% alcohol, grapes need to be around 21.7°Bx. For 15% alcohol, they need to be around 27.1°Bx. Most table wines fall between these two.

Checking Acid Levels

As sugar goes up, acid goes down. All wines need some acidity to taste balanced and not flat. Acidity is also important for food and wine pairing. Winemakers try to pick grapes before acid levels get too low. If acids are too low, winemakers can add them later. But it's best if the grapes have natural acids, as they help with flavor and fight against spoilage.

The main acids in wine are tartaric and malic acid. "titratable acidity" or "TA" measures the tartaric acid. This is the most common acid and has the biggest impact on the wine's taste. TA is measured by adding a special solution to grape juice until it changes color. This tells them how much tartaric acid was in the juice. TA levels are given as a percentage. For still table wines, TA is often between 0.60-0.80% for red grapes and 0.65-0.85% for white grapes.

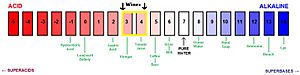

pH Level

The pH level measures how many free hydrogen ions are in the wine. It's related to TA but different. Low pH means lots of acid. Pure water has a pH of 7, but wine is more acidic, usually between 3 and 4. As grapes ripen and acid levels fall, the pH level goes up. Yeasts, bacteria, and color compounds are all affected by pH. Wines with high pH often have duller colors and less flavor. They are also more likely to spoil. So, checking pH levels is very important for winemakers.

Simple pH indicator strips aren't accurate enough for winemaking. Most wineries use a pH meter that gives very precise readings. For white wines, winemakers often look for pH readings between 3.1 and 3.2, with 3.4 as a maximum. If the pH is too high, it might mean the grapes are overripe. Winemakers can add acid to fix high pH. Many winemakers use pH readings as a key sign for when to start the harvest.

Balancing Sugar, Acidity, and pH

The perfect situation for a winemaker is when sugar, acidity, and pH are all perfectly balanced at harvest time. For example, ideal red table wine grapes might have 22 Brix, 0.75 TA, and 3.4 pH. But as winemaker Jeff Cox says, this "royal flush" is rare! With all the different climates, soils, grape types, and weather each year, winemakers learn to find the best compromise. They pick the grapes when they are most aligned with their vision for the final wine.

There are formulas to help. One from the University of California-Davis is the Brix:TA ratio. This uses the ratio of brix degrees to TA measurements. For example, 22°Bx and 0.75 TA gives a 30:1 Brix:TA ratio. Researchers say the most balanced table wines have a Brix to TA ratio between 30:1 and 35:1. Another method is to multiply the pH reading by itself, then multiply that by the Brix reading. For white wine grapes, a number close to 200 is good. For red wine grapes, close to 260 is good. For example, white grapes with a pH of 3.3 and Brix of 20 would give 217.80, which is a good harvest range for some winemakers.

Physiological Ripeness

The idea of physiological ripeness is a newer way to think about grapes. It includes factors that affect wine quality beyond just sugar, acid, and pH. These factors include how ripe the tannins are and how other compounds that give color, flavor, and smell have developed. This idea is similar to the French word engustment, which means the stage when flavor and aroma become clear. Research shows that most aroma compounds develop later in ripening, after sugar levels have settled. This is different from sugar/acid ripeness. A grape can be "ripe" in terms of sugar and acid, but still not fully developed in its tannins, aromas, and flavors.

Most of these qualities are hard to measure exactly. So, winemakers check physiological ripeness by looking at and tasting the grapes. With practice, they learn to connect certain tastes and looks with different stages of development. They check the texture of the skin and pulp, and the color of the skins, seeds, and stems. If the seeds are still green, the tannins inside are likely harsh and bitter. As tannins develop, the seeds get darker. Winemakers also look at the lignification of the stems. They turn from green and flexible to hard, woody, and brown. This shows the vine has finished developing its grapes and is storing energy for next year. Winemakers constantly taste grapes in the weeks before harvest.

Flavor Precursors and Glycosides

Even though it's hard to measure physiological ripeness exactly, scientists are working on ways to do it. For example, some wineries use near infrared (NIR) spectroscopy to measure the amount of color-giving anthocyanins in grape skins. A lot of research is also focused on finding "flavor precursors" and "glycosides" in ripening grapes.

Flavor precursors are compounds in grapes that don't have a taste yet. They are more common than other flavor compounds called flavonoids. Examples include monoterpenes, which give Riesling and Muscat their floral smell, and methoxypyrazine, which gives Cabernet Sauvignon and Sauvignon blanc a "green-bell pepper" smell. When these compounds are "free," they are flavor compounds. But when they combine with sugars, they become glycosides or "flavor precursors." These compounds are released later, during winemaking and aging, and they add to the wine's flavor. In theory, grapes with more flavor precursors can make higher quality wine.

Scientists have found ways to detect these compounds in grapes before harvest. One way is using special machines called gas chromatograph-mass spectrometers. Another method is the glycosyl-glucose assay. This method isolates glycosides from grape juice and then breaks them down to get glucose. The amount of glucose tells them how many glycosides were in the grape. The link between glycosides in grapes and wine quality isn't an exact science, but it's an area where research continues.

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |