Ancient Roman cuisine facts for kids

The cuisine of ancient Rome changed a lot during its long history. What Romans ate was affected by big political shifts, like when Rome went from being a kingdom to a republic, and then a huge empire. As the empire grew, Romans learned about many new foods and cooking styles from different places.

At first, there wasn't a huge difference in food between rich and poor Romans. But as the empire expanded, these differences became much bigger.

Contents

Finding Out About Roman Food

Most foods from ancient times rot away. But things like ashes and animal bones give us clues about what ancient Romans ate. For example, tiny plant remains have been found in a cemetery in Spain. When Boudica's army burned a Roman shop in Colchester, imported figs were preserved as charred remains.

In Herculaneum, a city destroyed by Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, archaeologists found chickpeas and bowls of fruit. In the city's sewers, they found tiny fish bones, sea urchin spines, and plant remains. They identified dill, coriander, flax, lentils, cabbage, and many kinds of nuts, fruits, and legumes. At Pompeii, grapes, bread, and pastry were found burned in gardens, left as offerings to household gods.

Roman Meals and Eating Habits

Traditionally, Romans ate a breakfast called ientaculum at sunrise. Their main meal, cena, was eaten in the middle of the day. A light supper, vesperna, was eaten at night.

As more foreign foods arrived, the cena became bigger and included more types of food. It slowly moved to the evening, and the vesperna eventually disappeared. The mid-day meal, prandium, became a light snack to last until the evening cena. For working-class Romans, these changes were less common because their daily routines matched their manual labor.

However, for wealthy Romans who didn't do manual labor, it became normal to finish all their business in the morning. After prandium, they would finish any last tasks and visit the baths. Around 2 p.m., the cena would begin. This meal could last late into the night, especially if guests were invited. It was often followed by comissatio, a round of wine and other alcoholic drinks.

In early Roman times, the cena was mainly a type of porridge called puls. The simplest puls was made from emmer (a type of grain), water, salt, and fat. A fancier version used olive oil and was eaten with vegetables. Wealthy people often ate their puls with eggs, cheese, and honey. Sometimes, it was even served with meat or fish.

Over time, the cena grew to have two parts: a main course and a dessert with fruit and seafood. By the end of the Roman Republic, meals usually had three parts: an appetizer (gustatio), a main course (primae mensae), and dessert (secundae mensae).

Roman soldiers mainly ate wheat. By the 4th century, most soldiers ate as well as people in Rome. They received rations of bread and vegetables, along with meats like beef, mutton, or pork. Their food also depended on where they were stationed. Mutton was popular in Northern Gaul and Britannia, but pork was the main meat for soldiers.

Roman Foods and Ingredients

Roman colonies sent many foods to Rome. For example, ham came from Belgium, oysters from Brittany, and garum (a fish sauce) from Mauretania. Wild game came from Tunisia, and flowers from Egypt.

The ancient Roman diet included many foods still used in modern Italian cooking. Pliny the Elder wrote about over 30 types of olives, 40 kinds of pears, and many different figs and vegetables. Some of these vegetables are not found today, or they have changed a lot. Romans ate carrots of different colors, but not orange ones.

Many vegetables were grown and eaten, including celery, garlic, cabbage, kale, broccoli, lettuce, onions, leeks, asparagus, radishes, turnips, parsnips, beets, green peas, and cucumbers.

However, some foods common in modern Italian cooking were not used. For example, spinach and eggplant came later from the Arab world. Tomatoes, potatoes, capsicum peppers, and maize (corn, used for polenta) only arrived in Europe after the discovery of the New World. Romans knew about rice, but it was very rare. There were also few citrus fruits. Lemons were known in Italy from the 2nd century AD but were not widely grown.

Breads and Grains

From 123 BC, the Roman state gave out unmilled wheat (about 33 kg) to as many as 200,000 people each month. This was called the frumentatio. At first, there was a small charge, but from 58 BC, it became free. Only Roman citizens living in Rome could receive it.

Originally, Romans ate flat, round loaves made from emmer (a grain like wheat) with a little salt. Wealthy people also ate eggs, cheese, honey, milk, and fruit. Around 1 AD, bread made from wheat became popular. Over time, more wheat-based foods replaced emmer loaves. There were many types of bread. White bread was for the rich, darker bread for the middle class, and the darkest bread for the poor. Bread was sometimes dipped in wine and eaten with olives, cheese, and grapes. When Pompeii was destroyed in 79 AD, there were at least 33 bakeries in the city. Roman chefs made sweet buns with blackcurrants and cheesecakes with flour, honey, eggs, ricotta-like cheese, and poppy seeds. Sweet wine cakes were made with honey, red wine, and cinnamon. Fruit tarts were popular with the rich, but poor people couldn't afford them.

Juscellum was a broth with grated bread, eggs, sage, and saffron. This recipe is found in Apicius, a Roman cookbook from the late 4th or early 5th century.

Meat in Roman Meals

Butcher's meat was a rare luxury. The most popular meat was pork, especially sausages. Beef was not common in ancient Rome. Seafood, wild game, and poultry like ducks and geese were more common. For example, after his Roman triumph, Caesar gave a public feast to 260,000 poorer people that included seafood, game, and poultry, but no butcher's meat. Meat was mostly eaten at religious sacrifices and at dinner parties for the very rich. Cows were valued for their milk, and bulls for farm work. Meat from working animals was tough. Veal was sometimes eaten. The Roman cookbook Apicius has only a few recipes for beef, but many more for lamb or pork.

Dormice were eaten and seen as a special treat. They were a sign of wealth among rich Romans. Some even had dormice weighed in front of their dinner guests. A law was passed to stop people from eating dormice, but it didn't work.

Fish and Seafood

Fish was more common than meat. Romans had advanced ways of raising fish, with large businesses for oyster farming. They also farmed snails and oak grubs. Some fish were highly valued and very expensive, like mullet from the Cosa fishery. Romans found clever ways to keep fish fresh.

Fruit in Ancient Rome

Fruit was eaten fresh when it was in season. It was also dried or preserved for winter. Popular fruits included apples, pears, figs, grapes, quinces, citron, strawberries, blackberries, elderberries, currants, damson plums, dates, melons, rose hips, and pomegranates. Less common fruits were azeroles and medlars. Cherries and apricots, both brought to Rome in the 1st century BC, were popular. Peaches arrived in the 1st century AD from Persia. Oranges and lemons were known but used more for medicine than for cooking. Lemons were not widely grown in Italy until the Roman Empire. Romans grew at least 35 types of pears and three types of apples. There are recipes for pear and peach creams and milk puddings flavored with honey, pepper, and a little garum.

Columella gave advice on how to preserve figs by crushing them into a paste with anise, fennel seed, cumin, and toasted sesame, then wrapping them in fig leaves.

Vegetables in Roman Diet

While early versions of Brussels sprouts, artichokes, peas, rutabaga, and possibly cauliflower existed in Roman times, the types we know today were developed much later. Cabbage was eaten both raw (sometimes dipped in vinegar) and cooked. Cato the Elder thought cabbage was good for digestion.

Legumes

Legumes eaten by Romans included dried peas, fava beans (broad beans), chickpeas, lentils, and Lupines. Romans knew several kinds of chickpeas. They were either cooked into a broth or roasted as a snack. The Roman cookbook Apicius has several recipes for chickpeas.

Nuts

Ancient Romans ate walnuts, almonds, pistachios, chestnuts, hazelnuts, pine nuts, and sesame seeds. They sometimes ground nuts to thicken sweet wine sauces for roast meat and fowl. Nuts were also used in savory sauces for cold cuts. Nuts were used in pastries, tarts, and puddings sweetened with honey.

Dairy Products

Cheese was a common food, and making it was well-established by the Roman Empire. It was part of the standard food for Roman soldiers and popular among regular people. Emperor Diocletian (284–305 CE) even set maximum prices for cheese. Many Roman writers mentioned how cheese was made, its quality, and how it was used in cooking. Pliny the Elder described its uses for diet and medicine. Columella gave the most detailed description of Roman cheesemaking.

Condiments and Sauces

Garum was a special fish sauce unique to ancient Rome. It was used as a seasoning instead of salt, as a table condiment, and as a sauce. There were four main types of fish sauce: garum, liquamen, muria, and allec. It was made in different qualities from fish like tuna, mullet, and sea bass. It could be flavored, for example, mixed with wine, or diluted with water (hydrogarum), which was popular among Roman soldiers. The most expensive garum was garum sociorum, made from mackerel in Spain and traded widely. Pliny wrote that two large jars of this sauce cost 1,000 sesterces, which was a lot of money.

Roman Cooking Methods

One way of cooking in ancient Rome was using the focus. This was a hearth placed in front of the lararium, the household altar for guardian spirits. In some homes, the lararium was built into the wall, and the focus was a raised brick structure where a fire was lit. More commonly, the focus was a rectangular, portable hearth with stone or bronze feet. After separate kitchens became common, the focus was used mostly for religious offerings and warmth, not for cooking.

Romans used portable stoves and ovens. Some had water pots and grills on them. In Pompeii, most houses had separate kitchens, usually small. A few were large, like the kitchen at the Villa of the Mysteries, which was nine by twelve meters. Many kitchens in Pompeii had no roofs, looking more like courtyards. This helped smoke escape. Kitchens with roofs must have been very smoky, as the only ventilation came from high windows or holes in the ceiling. Romans built chimneys for bakeries and blacksmiths, but not for private homes until around the 12th century AD.

Many Roman kitchens had an oven (furnus or fornax). Some, like the kitchen at the Villa of the Mysteries, had two. These ovens were square or dome-shaped, made of brick or stone, with a flat floor often made of granite or lava. Dry twigs were used to light fires inside them. On kitchen walls, there were hooks and chains for hanging cooking tools. These included various pots and pans, knives, meat forks, sieves, graters, spits, tongs, cheese-slicers, nutcrackers, jugs for measuring, and pâté molds.

Drinks in Ancient Rome

In Ancient Rome, wine was usually mixed with water before drinking. This was because the fermentation wasn't controlled, and the alcohol content was high. Winemakers sometimes changed or "improved" wine. Instructions exist for turning white wine into red and vice versa, and for saving wine that was turning into vinegar. These instructions, along with detailed descriptions of Roman winemaking, date back to 160 BC.

Wine was also flavored in different ways. For example, passum was a strong, sweet raisin wine. Mulsum was a fresh mix of wine and honey. Conditum was a mixture of wine, honey, and spices made in advance and aged. One special recipe, Conditum Paradoxum, was for a mix of wine, honey, black pepper, laurel, dates, mastic, and saffron, cooked and stored. Another recipe called for adding seawater, pitch, and rosin to the wine. A Greek traveler said this drink was probably an acquired taste. Sour wine mixed with water and herbs (posca) was a popular drink for poorer people and a main part of a Roman soldier's food.

Beer (cerevisia) was known but considered common. It was often linked to "barbarian" cultures.

Roman Desserts

Ancient Romans didn't have refined sugar or properly churned butter like we do today. However, they had many desserts to enjoy after their meals, often served with wine. The most famous desserts were large plates of fresh fruits. Some exotic fruits that couldn't grow in Rome were even shipped from far-off lands for the wealthy. Since there was no sugar, people always wanted the sweetest fruits available.

Sprias were a type of sweet pastry that was common. They had a thin, cake-like crust and sometimes contained fruit. Enkythoi was another common Roman pastry that was softer, like a modern sponge cake.

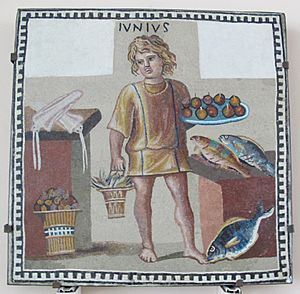

Images for kids

-

Still life with eggs, birds and bronze dishes, from the House of Julia Felix, Pompeii

See also

In Spanish: Gastronomía romana para niños

In Spanish: Gastronomía romana para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |