Werner Voss facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Werner Voss

|

|

|---|---|

Werner Voss, with the Pour le Mérite on his collar

|

|

| Born | 13 April 1897 Crefeld, Prussia, German Empire |

| Died | 23 September 1917 (aged 20) near Poelcappelle, West Flanders, Belgium |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

Luftstreitkräfte |

| Years of service | 1914–1917 † |

| Rank | Leutnant |

| Unit | 11th Hussar Regiment; Kampfstaffel 20; Jagdstaffel 2; Jagdstaffel 5; Jagdstaffel 10; Jagdstaffel 14; Jagdstaffel 29 |

| Awards |

|

Werner Voss (German: Werner Voß; 13 April 1897 – 23 September 1917) was a brave German flying ace during World War I. He was known for shooting down 48 enemy planes. Werner was the son of a dyer from Krefeld, Germany. He was a very patriotic young man, even when he was still in school.

Werner started his military journey in November 1914 as a 17-year-old Hussar (a type of cavalry soldier). Later, he switched to flying and quickly became a natural pilot. After flight school and serving in a bomber unit, he joined a new fighter squadron called Jagdstaffel 2 on November 21, 1916. There, he became good friends with Manfred von Richthofen, who was also known as the Red Baron.

By April 6, 1917, Voss had already won 24 victories. He was given Germany's highest award, the Pour le Mérite. He took a month off during a very tough time in the air war, called "Bloody April". Even though Richthofen got 13 more victories while Voss was away, Richthofen still saw Voss as his only real rival for being the top ace.

After his break, Voss returned to flying. He helped test new fighter planes and really liked the Fokker Triplane. He then led a few different squadrons for a short time. On July 30, 1917, at Richthofen's request, Voss was given command of Jagdstaffel 10. By this time, he had 34 victories.

His last battle happened on September 23, 1917, just hours after his 48th victory. Flying his silver-blue Fokker Dr.1, he bravely fought alone against eight British aces. These included famous pilots like James McCudden and Arthur Rhys-Davids. Voss showed amazing flying skills and shooting in the fight. He even hit every one of his opponents' planes with bullets. James McCudden, a British hero, called Voss "the bravest German airman." The pilot who shot Voss down, Arthur Rhys-Davids, wished he could have captured him alive. This famous air battle is still talked about by aviation historians today.

Contents

Werner's Early Life and Joining the Military

Werner Voss was born in Krefeld, Germany, on April 13, 1897. His mother, Johanna Mathilde Pastor Voss, was a religious homemaker. She raised her children in the Evangelical Lutheran faith. His father, Maxmilian, owned a factory that dyed fabrics. Werner had two younger brothers, Maxmilian Jr. and Otto. Two of his cousins, Margaret and Katherine, also lived with the family. The Voss parents wanted daughters, so they treated their nieces like their own children.

The Voss family lived in a nice two-story house with a yard. Werner was expected to take over the family business when he grew up. But even before World War I started, he felt a strong pull to serve his country. After finishing school, he joined the Krefeld Militia. In April 1914, even though he was too young for the army, Werner joined Ersatz Eskadron 2. For his 17th birthday, his parents gave him a Wanderer motorcycle. He got his motorcycle license on August 2, 1914.

When Germany entered World War I, Werner spent August and September 1914 driving for the German military as a volunteer. The Militia unit he joined sent new soldiers to the 11th Hussar Regiment. On November 16, 1914, Werner Voss officially became a soldier in this regiment, even though he was still only 17. On November 30, the hussar regiment was sent to fight on the Eastern Front.

Military Service: From Horses to Planes

Becoming a Pilot

Voss was good at his military duties on the Eastern Front. He was promoted to Gefreiter (a type of corporal) on January 27, 1915. Then, he became an Unteroffizier (a non-commissioned officer) on May 18, 1915, when he was barely 18 years old. For his service, he received the Iron Cross 2nd Class.

On August 1, 1915, Voss transferred to the Luftstreitkräfte (German Air Service). He joined a training unit in Cologne. On September 1, he started learning to fly in his hometown of Krefeld. Voss was a natural pilot. He flew his first solo flight on September 28. After he finished his training on February 12, 1916, he stayed at the school as an instructor. On March 2, he was promoted to Vizefeldwebel (a senior non-commissioned officer). He was the youngest flight instructor in the German air service.

First Air Battles

On March 10, 1916, Voss was sent to Kampfstaffel 20 (Tactical Bomber Squadron 20). He first served as an observer, then was allowed to fly as a pilot. He earned his pilot's badge on May 28, 1916, after flying real combat missions. On September 9, 1916, he became an officer. He then transferred to single-seater scout aircraft and joined Jagdstaffel 2 (Fighter Squadron 2) on November 21, 1916.

Here, Voss became very good friends with Manfred von Richthofen, the famous Red Baron. They often flew together in combat. Their friendship was strong, even though they came from different family backgrounds.

Voss loved machines, especially motorcycles. He often spent time with his mechanics, Karl Timms and Christian Rueser, and even called them by their first names. They later moved to other squadrons to stay with him. Voss sometimes ignored uniform rules. He would work on his plane in the hangar with the mechanics, wearing a dirty jacket without his rank badges. He even decorated his Albatros D.III plane with a swastika and a heart for good luck. While he dressed casually on the ground, he wore a silk shirt under his flying gear when he flew. He joked that he wanted to look good for the girls in Paris if he was captured. The silk collar also protected his neck from rubbing while he looked around for other planes.

Voss got his first air victory on November 26, 1916. He got a second victory later that day. For these two wins, he received the Iron Cross First Class on December 19, 1916. His first victory of 1917, against Captain Daly, taught Voss how to shoot accurately at moving targets. Voss even visited Daly in the hospital twice.

Voss's number of victories grew quickly in February and March 1917. Out of 15 victories for his squadron in March, he shot down 11 of them himself. For his brave actions, he received the Knight's Cross with Swords of the Order of Hohenzollern on March 17. The next day, Voss shot down two British planes in just ten minutes. One plane caught fire, and the other crash-landed behind German lines. The British pilots who were captured complained that Voss had shot at them after they had landed.

After his 23rd victory on April 1, Voss again shot at the pilot and his plane after it had crash-landed. On April 6, 1917, he claimed two more victories within 15 minutes. He shot down a two-seater scout plane and a Sopwith Pup. The two-seater pilot bravely got out of his plane to save aerial photos, even with Voss shooting at him and German artillery firing. The Sopwith Pup was later seen with German markings, but Voss's victory was not officially confirmed because it landed behind German lines.

Voss received the Pour le Mérite on April 8, 1917. It was common for winners of this award to get a month of leave. Voss immediately went home for his holiday. He did not return to fighting until May 5. By the time of this break, Voss had become very skilled at shooting and knowing what was happening around him in battle.

His holiday allowed him to spend Easter and his birthday at home. There was a big family reunion. He took a formal photo wearing his Pour le Mérite. He also worked on his motorcycle and rode it around. He was out of action during "Bloody April," when the German Air Service caused heavy losses for the British Royal Flying Corps. Richthofen, who had 11 victories before Voss started his own count, got 13 more victories while Voss was away. Richthofen called Voss his "most redoubtable competitor."

When Voss returned from leave, he was not happy with his commanding officer, Franz Walz. Voss felt Walz was not aggressive enough. Voss complained to higher command about Walz. Because of this, all three men were moved out of the squadron. Voss was sent to Jagdstaffel 5 to take temporary command on May 20, 1917.

Voss as a Commander

Voss was given an Albatros D.III plane with his new squadron's markings. During his short time with Jasta 5, Voss scored six more victories. On May 9, 1917, he shot down or forced down three Allied planes. This was the first of two times he would achieve three victories in one day. However, he was not always successful. On May 28, 1917, after his 31st victory, he was one of three German pilots who attacked Captain Keith Caldwell of 60 Squadron. Caldwell's plane was badly damaged, but the New Zealander managed to escape.

Voss was slightly hurt on June 6, 1917, by Flight Sub-Lieutenant Christopher Draper. But he quickly returned to duty. Voss then went on leave with Richthofen to Krefeld. Photos show them showing off their planes to Voss's family. After his leave, on June 28, Voss took temporary command of Jagdstaffel 29. Just five days later, he was given temporary command of Jagdstaffel 14.

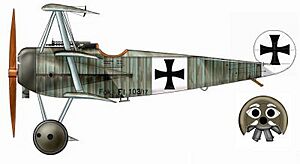

Voss was one of the first pilots to test the F.I. triplane prototype, which later became the famous Fokker Dr.I. He tested the Fokker F.I. s/n 103/17 on July 5, 1917. Even though the Fokker was slow in a dive, Voss loved it. It was easy to fly, could turn better than any other plane, had two machine guns, and could climb very fast. This climbing ability helped pilots quickly gain height over opponents. Voss strongly suggested that the Fokker be used in combat.

On July 30, Voss took permanent command of Jagdstaffel 10 in Richthofen's Flying Circus, Jagdgeschwader I (JG I). He replaced Ernst Freiherr von Althaus at Richthofen's request. He was given a new silvery Pfalz D.III plane. However, Voss thought it was not as good as his green Albatros D.V. He may have scored four victories with the Pfalz. Voss was a "loner" and did not like the paperwork and duties of being a commander. Another officer, Oberleutnant Ernst Weigand, handled the daily tasks. Voss often rode his motorcycle around the airfield instead of using his staff car.

In late August 1917, the Fokker F.I. prototype with its rotary engine was given to Voss as his personal plane. As a child, Voss had flown Japanese fighting kites with his cousins. This gave him the idea to paint the front of his triplane with two eyes, eyebrows, and a mustache. Many famous people came to see the new fighter. On August 31, Anthony Fokker (the plane's designer) brought German Chancellor Georg Michaelis and Major General Ernst von Lossberg to see and film the new triplane. On September 9, Crown Prince Wilhelm also visited Jagdstaffel 10.

By September 11, 1917, Voss had 47 victories. This was second only to the Red Baron's 61. During this time, he had his closest call in combat. After shooting down ace Oscar McMaking, Voss was attacked by Captain Norman Macmillan. Macmillan flew his Sopwith Camel very close to Voss, and machine gun bullets almost hit Voss's head. Macmillan saw Voss turn his head twice to check the Camel's position before dodging. Then, a Royal Aircraft Factory RE.8 flew between them, almost crashing into the Camel and stopping the attack as Voss dived away. Macmillan claimed a victory, but Voss returned to base with a damaged plane.

The next day, Voss took leave as a squadron leader. He first went to Berlin, where he received a signed photo of Kaiser Wilhelm II from the emperor himself. From the 15th to the 17th, he was at the Fokker factory with his girlfriend Ilse. He was also allowed to visit Düsseldorf and his hometown of Krefeld, but it is not known if he did. He returned to duty on September 22, 1917.

Voss's Final Patrol

Voss returned from leave on September 23, 1917, not fully rested. A fellow pilot, Leutnant Alois Heldmann, said Voss seemed "nervous." Still, Voss flew a morning mission and shot down an Airco DH.4 from No. 57 Squadron RFC at 9:30 AM. When he returned to base with bullet holes in his Fokker, he did a victory loop before landing, since Richthofen was away. Voss was wearing striped gray trousers, a dirty gray sweater, and tall lace-up boots, not his usual neat flying clothes.

Just before Werner landed, his brothers Max and Otto Voss arrived for a visit. Otto was a 19-year-old army leutnant who wanted to become a pilot like his older brother. Max Jr. was a 16-year-old sergeant. Voss was tired and told his brothers he looked forward to more time off. They ate lunch together. His brothers noticed he looked worn out, which can be seen in his last photos. After lunch, the three posed for a photo using Werner Voss's camera with a timer. Then, Voss was scheduled for another patrol.

At the same time, on the British side, No. 56 Squadron RFC was getting ready for its afternoon patrols. 'B' Flight was led by Captain James McCudden. His Royal Aircraft Factory SE5a plane had a large 'G' painted on its side. Two other aces, Captain Keith Muspratt and Lieutenant Arthur Rhys-Davids, followed him. Three other pilots were also with 'B' Flight.

'C' Flight, led by Captain Geoffrey Hilton Bowman, was also getting ready. Lieutenant Reginald Hoidge and another ace, Lieutenant Richard Maybery, were in 'C' Flight.

Both flights of 56 Squadron took off at 5:00 PM. They climbed into a sky with a thick cloud ceiling at 2,700 meters (about 8,850 feet). McCudden noted that visibility was good horizontally, but hazy on the ground. German anti-aircraft fire was heavy. As 'B' Flight continued its patrol, McCudden shot down a German DFW at 6:00 PM. Rhys-Davids fired at it as it fell.

On the German side, Voss had changed clothes. He wore a colorful silk shirt under his brown leather coat. His polished brown boots shone. His Pour le Mérite medal was at his throat. He was to lead one of the afternoon patrols. His wingmen were Leutnant Gustav Bellen and Leutnant Friedrich Rüdenberg. After taking off at 6:05 PM, Voss, in his new Fokker Triplane, quickly left his slower wingmen behind. A few minutes later, Oberleutnant Ernst Weigand led a second flight. None of these planes could catch up with Voss.

The Battle Begins

The air battle started over Poelkapelle around 6:30 PM. The Germans chasing Voss were stopped by British Sopwith Camels, SPADs, and Bristol F.2 Fighters. Two flights of the skilled 56 Squadron were flying lower, at 1,800 meters (about 5,900 feet). Below that, Lieutenant Harold A. Hamersley of 60 Squadron saw a group of German planes. He turned to help what he thought was a Nieuport plane being attacked by a German Albatros. He fired a short burst to distract the German.

The "Nieuport" was actually Voss's Fokker Triplane. Voss quickly turned on Hamersley and fired his machine guns, hitting his wings and engine. Hamersley spun his plane to escape, with Voss still firing at him. Lieutenant Robert L. Chidlaw-Roberts rushed to help. Within seconds, Voss hit Chidlaw-Roberts's plane, forcing him out of the fight.

While Hamersley and Chidlaw-Roberts fell away, Voss was attacked by 'B' Flight of 56 Squadron. Captain McCudden and his wingmen attacked from 300 meters (about 980 feet) above Voss. McCudden attacked from the right, while Lieutenant Arthur Rhys Davids attacked from the left. Voss did not try to escape. Instead, he spun his triplane and fired at his attackers head-on, hitting McCudden's wings. Voss then hit Cronyn's plane from close range, forcing him out of the fight.

At this point, 'C' Flight arrived. Bowman and Maybery joined the attack on Voss. Hoidge also joined the battle.

Voss, in his triplane, twisted and turned among his many attackers. He never flew straight for more than a few seconds. He dodged British fire and shot at all of them. The fight became so fast and confusing that the pilots later gave different accounts. However, some things were agreed upon:

- Muspratt's engine lost its coolant early on from a bullet. He glided away from the fight.

- At one point, a red-nosed Albatros D.V. tried to help Voss, but Rhys-Davids hit its engine, and it left the fight.

- Voss was caught in a crossfire by at least five attackers but seemed unharmed. Maybery left the fight with his plane damaged.

Voss and the six remaining British aces spiraled down to 600 meters (about 1,970 feet). Sometimes Voss was higher than his attackers, but he did not try to escape. He used his triplane's fast climb rate and ability to turn quickly to dodge his opponents. He kept turning and attacking any plane chasing him. Bowman later said that Voss "kicked on full rudder... gave me a burst while he was skidding sideways." Bowman's plane was hit and slowed down, but he stayed in the fight.

Death in the Sky

Then, after flying head-on at McCudden, Voss's plane was hit by machine-gun fire from Hoidge. After this, Voss stopped moving his plane around and flew level for the first time. At this moment, Rhys-Davids, who had pulled away to change ammunition, rejoined the battle. He was 150 meters (about 490 feet) higher than Voss, who was at 450 meters (about 1,475 feet). Rhys-Davids began a long dive towards the back of Voss's triplane, which did not react. At very close range, he fired at Voss's plane before breaking away. A few seconds later, Voss's plane drifted into Rhys-Davids's path again, in a slow glide to the west. Rhys-Davids fired another long burst, causing the engine to stop. The two planes almost crashed into each other. As the triplane's glide became steeper, Rhys-Davids flew past it at about 300 meters (about 980 feet) and lost sight of Voss's plane below his own. From above, Bowman saw the Fokker as if it were trying to land, until it suddenly stalled. It then flipped upside down and nose-dived straight to the ground. Only the rudder remained after the crash.

McCudden, watching from 900 meters (about 2,950 feet), remembered: "I saw him go into a fairly steep dive... and then saw the tri-plane hit the ground and disappear into a thousand fragments, for it seemed to me that it literally went into powder."

Voss had fought the British aces for about eight minutes. He dodged them and hit almost every British plane. His damaged plane crashed near Plum Farm in Belgium around 6:40 PM.

Aftermath

British Reaction

Lieutenant Verschoyle Phillip Cronyn later described his difficult flight back. He was one of the few pilots to escape Voss's gunfire. He had to fly his damaged plane home, which was almost falling apart. He lost control while trying to land and made a fast, desperate landing around 6:40 PM, about the same time Voss's triplane crashed. His squadron commander, Major Blomfield, helped the shaken pilot from his plane and gave him some brandy. Cronyn became very emotional, but then pulled himself together as McCudden and Rhys-Davids landed. Rhys-Davids was breathing fast and stammering from excitement. He also got brandy and gave a jumbled account of the fight.

The mood in the 56 Squadron mess that night was quiet. They wondered who their fallen opponent was. Names like Richthofen, Voss, and Wolff were suggested. Rhys-Davids received many congratulations, but he humbly said, "If I only could have brought him down alive."

The next day, September 24, 1917, a British patrol reached the crash site. Documents in Voss's pocket identified him. Werner Voss was buried like any other soldier near Plum Farm, in a shell crater without a coffin or special honors. His grave was later lost due to the ongoing fighting.

That same day, Maurice Baring was sent by Major General Hugh Trenchard to gather information about the air battle. Baring interviewed McCudden, Maybery, Hoidge, and Rhys-Davids. McCudden simply reported that the crash was near Zonnebeke. Maybery said he saw two triplanes in the fight, a gray one and a green one, plus other German planes. Hoidge did not see the red-nosed Albatros. Rhys-Davids said the fight started when a red-nosed Albatros, a green German scout, and a gray and brown Triplane attacked an SE.5. He also thought the triplane had four guns and a stationary engine instead of a rotary engine. Later stories about Voss's last stand would use these "facts" from Baring's report.

Rhys-Davids, in a letter home on September 25, mentioned his victory but did not know his victim's name. However, another letter on September 28 mentioned Voss by name. Also, on September 28, V. P. Cronyn was sent to a non-combat job due to combat fatigue.

On October 1, 1917, the British Headquarters in France and Belgium announced that "Lieut. Vosse... has been found within the British lines." British airmen had already dropped messages behind German lines to tell them of his death. The credit was given only to "a British airman." By October 5, Rhys-Davids's letter to his mother boasted about his souvenir rudder and compass from the triplane wreckage.

On October 27, the same day Rhys-Davids died in action, a British intelligence officer finally reached the wreckage. He confirmed it was a triplane. He noted its top surfaces were camouflage green and its bottom surfaces were blue. He took some small pieces from the wreck to go with his report. This information gave the British their first look at the new plane, even though Voss had put a French Le Rhone engine in it.

German Reaction

Leutnants Rüdenberg and Bellen returned to base, as did the other Jasta 10 pilots. Only Heldmann had news, reporting that Voss had flown towards British lines while an SE.5 chased him. Timm and Rueser anxiously waited for him as the sun set. The news that Voss was missing was sent to wing headquarters. Calls were made to all friendly airfields. Late that night, a German unit reported seeing six British planes shoot down a lone German aircraft that fell within British trenches. Heldmann refused to believe Voss was killed in the air. He claimed Voss must have been shot after crawling from the wreckage.

On September 24, Jasta 10 pilots dropped a note over British lines asking about Voss. By September 25, two days after the fight, the Niederrheinische Volkszeitung newspaper announced Voss's death. That same day, Jasta 10 lost its second commander in three days when Weigand was killed.

On October 7, 1917, the Krefelder Zeitung newspaper published tributes to Werner Voss. These included messages from Crown Prince Wilhelm, plane designer Anthony Fokker, and Generalleutnant Ernst von Hoeppner.

On October 11, 1917, Bellen left Jasta 10 due to illness. In November, Rüdenberg left active duty to go to university. Some historians believe these moves were punishment for not helping Voss in his battle.

Werner Voss's Legacy

When the British aces of 56 Squadron learned who their fallen enemy was, they quickly praised him. James McCudden VC, the leading British pilot in the fight, truly regretted Voss's death. He said: "His flying was wonderful, his courage magnificent and in my opinion he was the bravest German airman whom it has been my privilege to see fight."

Years later, Voss was not forgotten. Because his grave was lost, Werner Voss is one of 44,292 German soldiers remembered at the Langemark German war cemetery in Belgium. During the Nazi era, Voss's old school in Krefeld was renamed in his honor. This name was changed back after Germany lost World War II. However, a main road in Krefeld is still named after him. He is also remembered with street names in Stuttgart and Berlin.

People still debate why Voss chose to keep fighting against such overwhelming odds instead of trying to escape. Some think he wanted to catch up to the Red Baron's number of victories. Although British reports from the time do not mention Voss refusing to retreat, McCudden later said that Voss seemed to turn down chances to get away safely. In 1942, authors received letters from Chidlaw-Roberts and Bowman recalling Voss's last stand. Bowman believed Voss had a chance to escape but chose to fight despite the impossible situation. This is the earliest known source for the idea that Voss refused to retreat. The air battle remains a topic of discussion among aviation historians.

|

See also

In Spanish: Werner Voss para niños

In Spanish: Werner Voss para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |