White slave propaganda facts for kids

White slave propaganda was a term for public efforts, like photos, drawings, books, and talks, that showed enslaved people who looked biracial or even white. These examples were used before and during the American Civil War. Their goal was to help the abolitionist movement, which wanted to end slavery. They also helped raise money for schools for formerly enslaved people.

These images often showed children with mostly European features next to dark-skinned adult slaves with typical African features. The idea was to shock people watching. It reminded them that enslaved people were human, just like them. It also showed that enslaved people were not "different" or "other."

Contents

History of Slavery and Mixed Heritage

By 1860, about 10% of the 4 million enslaved people in the US had mixed racial backgrounds. There were more mixed-race enslaved people in the Upper South. Slavery had been around longer there. Also, enslaved people often lived closer to white workers and masters on smaller farms. This led to more mixing between groups. Studies show that African Americans today have, on average, about 24% European DNA.

In the 1930s, a project called the WPA collected stories from former slaves. When women talked about their parents, about one-third of them said they had a child with a white father. Or they said their own father was white. The difficult situation of these mixed-race enslaved people, especially children, was often shared to help the abolitionist cause.

Some people who supported slavery wanted it to be legal everywhere. They even suggested that white workers in the North would have better lives as slaves.

How Abolitionists Used "White Slaves"

Abolitionists used stories and images of light-skinned enslaved people in different ways. They wanted to show how cruel slavery was, no matter a person's skin color.

Stories and Books

The first abolitionist novel was The Slave: or Memoirs of Archy Moore, published in 1836. It was written by Richard Hildreth. The main character was a mixed-race enslaved hero. His father was a white plantation owner, and his enslaved mother was also the daughter of a white plantation owner. He could say that he had "the best blood of Virginia" from both sides of his family. When he and his sister decided to escape, they easily passed as white citizens. A later version of the book in 1852 was even called The White Slave; or, Memoirs of a Fugitive.

In the famous 1852 novel Uncle Tom's Cabin, there is a character named Eliza. She was described as a "quadroon" slave, meaning she had one-quarter black ancestry. Her child also looked almost white.

Another popular book was Mary Hayden Pike's Ida May: a Story of Things Actual and Possible (1854). This story was about an enslaved person who looked white. In 1855, a young mixed-race enslaved girl named Mary Mildred Botts became free. She looked white. Her father got help from abolitionists to buy her freedom, along with his wife and two other children. One person who helped was US Senator Charles Sumner from Massachusetts, who adopted her. Many people thought she was like the character Ida May from the book.

Newspapers like the Boston Telegraph and the New York Times wrote articles about her. Pictures of her were shared widely. Mary Mildred Botts appeared on stage with Senator Sumner and other abolitionists. She sat with them while they gave talks, and she was introduced as a former slave. In 1856, Senator Sumner gave a speech in the Senate. Two days later, he was attacked and seriously injured on the Senate floor by a Representative from South Carolina.

Years after slavery ended, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper wrote the novel Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted in 1892. It tells the story of a "colored" family before and after slavery. Most of the family members had so much European ancestry that they could easily pass for white. Only Iola's grandmother looked "unmistakably colored." When Iola's uncle, Robert Johnson, escaped slavery and became a hero in the Union army, a white officer told him: "You do not look like them, you do not talk like them. It is a burning shame to have held such a man as you in slavery." Johnson replied that it was just as wrong to enslave him as it was to enslave "the blackest man in the South."

True Stories

Some formerly enslaved people who looked European wrote true stories about how they used their appearance to "pass for white" and gain freedom. One such story was Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom by Ellen Craft, written with her husband William. Ellen Craft had mostly white ancestors. She often spoke at abolitionist events.

The Crafts and other abolitionists also shared the story of Salomé Müller. She was a German immigrant who became an orphan as a baby in New Orleans. Even though she was completely of European descent, she was enslaved as a baby. People just assumed she was a mixed-race slave. The fear that white girls could be taken and enslaved made Parker Pillsbury write to William Lloyd Garrison: "A white skin is no security whatsoever. I should no more dare to send white children out to play alone...than I should dare send them into a forest of tigers and hyenas."

Fannie Virginia Casseopia Lawrence was a young white-appearing enslaved girl who gained freedom in early 1863. A woman named Catherine S. Lawrence from New York adopted her. She was baptized by a famous preacher, Henry Ward Beecher, in Brooklyn, New York. Small photographs of her, called carte de visite, were sold to raise money for the abolitionist cause.

A Special Case: Freed Slaves from Louisiana

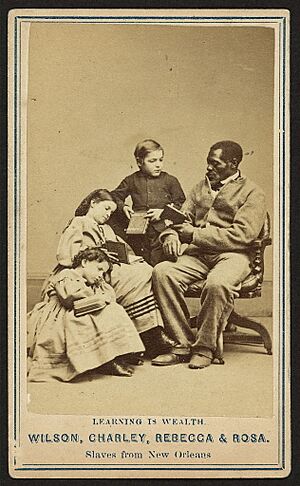

By 1863, in parts of Louisiana controlled by the Union Army, there were 95 schools for freedmen (formerly enslaved people). About 9,500 students attended these schools. Money was needed to keep them running. So, groups like the National Freedman's Association and the American Missionary Association, along with Union officers, started a public campaign. They sold small photographs, called carte de visite (CDV), of eight formerly enslaved people. There were five children and three adults.

Colonel George H. Hanks traveled with these formerly enslaved people on a tour of Philadelphia and New York. A drawing, based on a photo of them, appeared in Harper's Weekly in January 1864. The drawing's caption was "EMANCIPATED SLAVES, WHITE AND COLORED." Four of the children looked mostly white, even though they had been born into slavery.

The group traveled from New Orleans to the North. Four of the children looked white or "octoroon" (meaning one-eighth black ancestry). According to the Harper's Weekly article, they were described as "perfectly white," "very fair," or "of unmixed white race." Their light skin was a strong contrast to the darker skin of the three adults, Wilson, Mary, and Robert, and the fifth child, Isaac. Isaac was described as "a black boy of eight years; but nonetheless [more] intelligent than his whiter companions."

Colonel Hanks from the 18th Infantry Regiment went with the group. They posed for photos in New York City and Philadelphia. These photos were made into carte de visite cards and sold for twenty-five cents each. The money went to Major General Nathaniel P. Banks in Louisiana to support education for freedmen. Each photo noted that the money from sales would be "devoted to the education of colored people."

Many of these photos were made. At least twenty-two still exist today. Most were produced by Charles Paxson and Myron Kimball. They took the group photo that later became the drawing in Harper's Weekly. A portrait of Rebecca was taken by James E. McClees of Philadelphia.

Images for kids

-

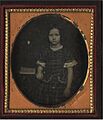

Mary Mildred Botts/Williams in an 1855 daguerreotype

See also

- Julia Chinn

- Louisa Picquet

- Mary Mildred Williams

- White slavery

- Garafilia Mohalbi

- Wilson Chinn

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |