Witold Lutosławski facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Witold Lutosławski

|

|

|---|---|

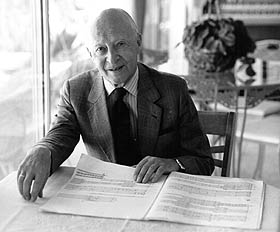

Lutosławski in 1992

|

|

| Born |

Witold Roman Lutosławski

25 January 1913 Warsaw, Congress Poland, Russian Empire

|

| Died | 7 February 1994 (aged 81) Warsaw, Poland

|

| Education | University of Warsaw |

| Occupation |

|

|

Works

|

List of compositions |

| Awards | Full list |

Witold Roman Lutosławski (born January 25, 1913 – died February 7, 1994) was a famous Polish composer and conductor. Many people believe he was the most important Polish composer since Karol Szymanowski and even Frédéric Chopin.

Lutosławski wrote many different kinds of music, like symphonies, concertos (pieces for a solo instrument and orchestra), and other works for orchestras. Some of his most well-known pieces are his four symphonies, the Variations on a Theme by Paganini (1941), the Concerto for Orchestra (1954), and his Cello Concerto (1970).

When he was young, Lutosławski studied piano and composition in Warsaw. His early music was inspired by Polish folk music. Later, in the late 1950s, he started using new and unique ways to compose. He added a bit of chance to his music, called limited aleatoric elements. This meant some parts of the music were not perfectly timed, but he still kept strong control over the overall sound and structure.

During World War II, Lutosławski played piano in Warsaw bars to earn money. After the war, the government in Poland (which was under Soviet influence) banned his First Symphony. They said it was "formalist," meaning it was too complex for ordinary people. Lutosławski strongly disagreed with this censorship. He always tried to keep his artistic freedom. He also supported the Solidarity movement in the 1980s, which fought for freedom in Poland. He received many important awards and honours for his music and his bravery.

Contents

Life and Career

Early Years (1913–1938)

Witold Lutosławski was born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1913. His family owned large estates. His father, Józef, was involved in Polish politics, working to make Poland an independent country again. At this time, Poland was divided among other empires.

In 1915, during World War I, the Lutosławski family moved to Moscow, Russia, to escape the fighting. Józef continued his political work there. However, after the Russian Revolution in 1917, the new Soviet government arrested Józef and his brother Marian. They were sadly executed in September 1918, when Witold was only five years old.

After the war, the family returned to a newly independent Poland. Their estates were ruined. Witold started piano lessons at age six. He later began studying violin and then composition at the Warsaw Conservatory. His main composition teacher was Witold Maliszewski, a student of the famous Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Lutosławski learned a lot about how to build musical structures. He also became a skilled pianist, earning a diploma in piano performance in 1936 and in composition in 1937.

World War II (1939–1945)

Lutosławski finished his Symphonic Variations in 1939. It was played on the radio just before Germany invaded western Poland and Russia invaded eastern Poland in September 1939. This invasion started World War II. Lutosławski was called to serve in the army but was captured by German soldiers. He managed to escape and walked 400 kilometers (about 250 miles) back to Warsaw. Sadly, his brother was captured by Russian soldiers and died in a labor camp in Siberia.

To make a living during the war, Lutosławski played piano in Warsaw cafés. He formed a piano duo with his friend, composer Andrzej Panufnik. They played many different songs, including Lutosławski's Variations on a Theme by Paganini. The Nazis had banned Polish music, but Lutosławski and Panufnik bravely played Polish songs anyway. Cafés were one of the few places Poles could hear live music.

In July 1944, Lutosławski left Warsaw with his mother, just before the Warsaw Uprising. When the city was destroyed by the Germans after the uprising failed, most of his music was lost. He only saved a few pieces. After the war, he returned to the ruined city.

Post-War Years (1946–1955)

After the war, Lutosławski worked on his First Symphony, which he had started in 1941. It was first performed in 1948. To support his family, he also wrote "functional" music, like the Warsaw Suite for a film about the city's rebuilding, and children's songs.

In 1946, he married Danuta Bogusławska. She was very helpful to him, becoming his copyist and helping him write down his complex musical ideas.

Around 1947, the government in Poland, influenced by the Soviet Union, began to control art and music. They said new music had to follow "socialist realism," meaning it should be simple and easy for everyone to understand. They banned Lutosławski's First Symphony, calling it "formalist." Lutosławski strongly disagreed with this censorship and resigned from a composers' committee.

Despite the difficult political situation, Lutosławski continued to compose. In 1954, he wrote his important Concerto for Orchestra. This piece helped him become known as a major composer of serious music. It won him two state prizes.

Becoming Famous (1956–1967)

After Joseph Stalin died in 1953, the rules about art became a bit less strict in Poland. In 1956, the Warsaw Autumn Festival of Contemporary Music was started. This festival allowed new and experimental music to be heard.

Lutosławski's Musique funèbre (meaning Funereal Music), finished in 1958, brought him international fame. He had worked on it for four years. In this piece, he developed his unique way of using harmonies and counterpoint (two or more melodies played at the same time). He also introduced a new technique called "limited aleatorism" in his piece Jeux vénitiens (Venetian Games). This meant that musicians played some parts without perfectly synchronizing, creating a slightly random, yet controlled, sound. These new techniques became a key part of his musical style.

From 1957 to 1963, Lutosławski also wrote some lighter music under the name Derwid. These were mostly waltzes and tangos for voice and piano.

In 1963, Lutosławski wrote Trois poèmes d'Henri Michaux for a choir and orchestra. This was his first piece commissioned from outside Poland and brought him more international praise. He also started working with a music publisher called Chester Music. His String Quartet was first played in 1965, followed by his song-cycle Paroles tissées.

Soon after, Lutosławski began his Second Symphony. It was very different from traditional symphonies. It used his new compositional ideas to create a large, dramatic work. In 1968, this symphony won him a major international award, showing his growing reputation worldwide. In 1967, he received Denmark's highest musical honor, the Léonie Sonning Music Prize.

International Recognition (1967–1982)

Lutosławski composed his Second Symphony, Livre pour orchestre, and a Cello Concerto during a difficult time in Poland. There were many protests and political tensions. Lutosławski did not support the Soviet-backed government. These events may have influenced the dramatic and sometimes tense feeling in his music, especially the Cello Concerto (1968–70). This concerto was written for the famous cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, who also opposed the Soviet government. The Cello Concerto was a huge success.

In the 1970s, Lutosławski wrote several other important pieces, including Les Espaces du sommeil (The Spaces of Sleep) for baritone and orchestra. He also worked on his Third Symphony and a piece for oboe and harp. The Double Concerto for oboe, harp and chamber orchestra was finished in 1980, and the Third Symphony in 1983.

During this time, Poland faced more political changes. The Solidarity movement, led by Lech Wałęsa, gained power in 1980. In 1981, martial law was declared, meaning the army took control. From 1981 to 1989, Lutosławski refused to take part in any official events in Poland. This was his way of showing support for artists who were boycotting the government. In 1983, he sent a recording of his Third Symphony to be played for striking workers in Gdańsk. He was very proud to receive the Solidarity prize that year.

Final Years (1983–1994)

In the mid-1980s, Lutosławski composed three pieces called Łańcuch (Chain). These pieces are built from different musical ideas that overlap, like links in a chain. Chain 2 was written for the famous violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter.

In 1985, his Third Symphony won the first Grawemeyer Prize, a very important award for music composition. Lutosławski used the prize money to create a scholarship fund for young Polish composers to study abroad.

In 1986, Lutosławski received the Royal Philharmonic Society's Gold Medal, a rare and prestigious award. He also received honorary doctorates from several universities around the world, including Cambridge.

He then wrote his Piano Concerto for the pianist Krystian Zimerman. Lutosławski himself had been a talented pianist when he was younger. In 1988, he conducted this piece and his Third Symphony at the Warsaw Autumn Festival. This marked his return to conducting in Poland after the government and opposition began talks.

Around 1990, Lutosławski worked on his Fourth Symphony and an orchestral song-cycle called Chantefleurs et Chantefables. The Fourth Symphony was first played in 1993. After the end of communist rule in Poland in 1989, Lutosławski became the president of the new "Polish Cultural Council."

Lutosławski continued to travel and compose in 1993, even sketching a violin concerto. However, in early 1994, he became very ill with cancer. He died on February 7, 1994, at the age of 81. A few weeks before he died, he received Poland's highest honor, the Order of the White Eagle.

Music

Lutosławski once said that composing music was like "fishing for souls," trying to connect with listeners who felt and thought like him.

Folk Music Influence

In his early works, up to Dance Preludes (1955), Lutosławski used Polish folk music as an inspiration. He didn't just copy folk tunes; he changed and transformed them in his own way. For example, in his Concerto for Orchestra, the folk influences are hidden and hard to recognize without careful study. As his style developed, he stopped using folk music so directly, but its influence remained in subtle ways. He called Dance Preludes his "farewell to folklore."

Pitch Organization

In Five Songs (1956–57) and Musique funèbre (1958), Lutosławski started using his own version of twelve-tone music. This was different from the traditional twelve-tone system. His method allowed him to build harmonies and melodies using specific musical intervals (the distance between two notes). This helped him create rich, full chords, sometimes using all twelve notes of the musical scale.

Aleatory Technique

In 1960, Lutosławski heard a piece by John Cage that used chance. This inspired him to find a way to keep his desired harmonies while adding freedom to the performance.

In his works from Jeux vénitiens onwards, Lutosławski wrote sections where musicians do not have to play perfectly together. The conductor gives cues, and each musician plays their part at their own speed. This creates a controlled randomness, which Lutosławski called "limited aleatorism." He wrote the music exactly as he wanted it to sound, so there was no improvisation. The musicians knew exactly what to play, but not exactly when to play it in relation to others.

For his String Quartet, Lutosławski only provided individual parts for each instrument. He didn't want a full score because he didn't want musicians to think notes had to line up perfectly. His wife helped solve this by cutting the parts into sections, which Lutosławski called mobiles, with instructions on when to move to the next section. In orchestral music, the conductor gives these instructions.

Example 1, from his Second Symphony, shows how this works. At number 7, the conductor cues the flutes, celesta, and percussion. They play their parts at their own pace. The harmony here uses specific intervals. After they finish, there's a short pause. At number 8, the conductor cues two oboes and a cor anglais. They play their parts freely. The harmony here is also carefully chosen. When the conductor cues at number 9, they continue until a repeat sign and then stop, likely at different times. This "refrain" is always played by double-reed instruments, showing Lutosławski's careful control over the sound of the orchestra.

Late Style

In his later works, Lutosławski's music became simpler and more flowing. He used less of the "ad libitum" (at will) coordination. This change appeared as he worked on his Third Symphony. Even in chamber music for just two instruments, he found ways to use his unique harmonic ideas.

Lutosławski's amazing musical developments came from his strong desire to create. He left behind many important compositions, showing his determination even when facing censorship from the authorities.

Legacy

Today, Lutosławski is seen as the most important Polish composer since Szymanowski, and perhaps even since Chopin. After World War II, his Concerto for Orchestra helped him become a leading figure in modern Polish classical music. He is considered one of the most significant European composers of the 20th century. His four symphonies, Variations on a Theme by Paganini (1941), Concerto for Orchestra (1954), and Cello Concerto (1970) are his most famous works.

Awards and Honours

Lutosławski received many awards and honors throughout his life, including:

- Order of Polonia Restituta, 1953

- Order of the Banner of Work, 1955

- Związek Kompozytorów Polskich (ZKP) Prize, 1959

- First Prize of the International Music Council's International Rostrum of Composers, 1959

- Koussevitzky Prix Mondial du Disque (France), 1964

- Grand Prix du Disque de Académie Charles Cros (France), 1965

- Jurzykowski Prize (United States), 1966

- Herder Prize (Germany/Austria), 1967

- Léonie Sonning Music Prize (Denmark), 1967

- First Prize of the International Music Council's International Rostrum of Composers, 1968

- Grand Prix du Disque de Académie Charles Cros (France), 1971

- Prix Maurice Ravel (France), 1971

- Honorary member of the Polish Composers' Union, 1971

- Wihuri Sibelius Prize (Finland), 1973

- Honorary degree of the University of Warsaw, 1973

- Koussevitzky Prix Mondial du Disque (France), 1976

- Order of the Builders of People's Poland, 1977

- Honorary degree of the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, 1980

- Ernst von Siemens Music Prize (Germany), 1983

- Honorary doctorate, Durham University 1983

- Honorary degree of the Jagiellonian University, 1984

- Queen Sofía Composition Prize (Spain), 1985

- Grawemeyer Award (United States), 1985

- Koussevitzky Prix Mondial du Disque (France), 1986

- Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medal (United Kingdom), 1986

- Grammy Award for Best Classical Contemporary Composition, 1987

- Honorary doctorate, University of Cambridge, 1987

- Honorary degree of the Fryderyk Chopin University of Music, 1988

- Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts, 1993

- Polar Music Prize (Sweden), 18 May 1993

- Kyoto Prize (Japan), 1993

- Honorary doctorate, McGill University, 30 October 1993

- Order of the White Eagle (Poland), 1994

See also

In Spanish: Witold Lutosławski para niños

In Spanish: Witold Lutosławski para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |