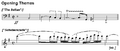

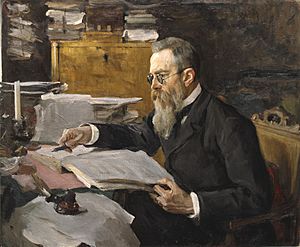

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov facts for kids

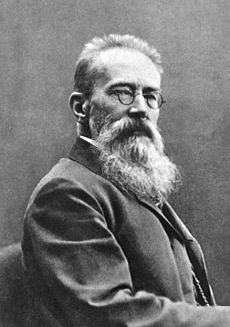

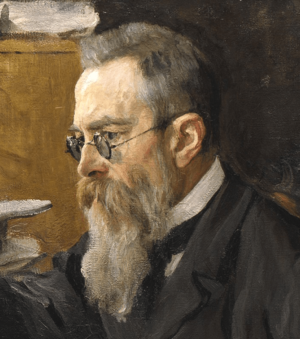

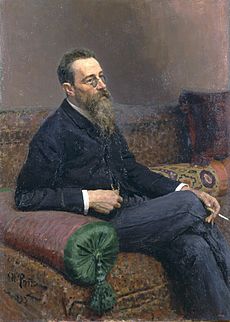

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov (born March 18, 1844 – died June 21, 1908) was a famous Russian composer. He was part of a group of composers known as The Five. He was especially good at writing music for orchestras, which is called orchestration.

Some of his most famous orchestral pieces include Capriccio Espagnol, the Russian Easter Festival Overture, and the musical story Scheherazade. These are still very popular in classical music today. Scheherazade shows how much he loved using fairy-tale and folk stories in his music.

Rimsky-Korsakov believed in creating a special Russian style of classical music. He used Russian folk songs and stories. He also added exciting and unusual sounds, rhythms, and tunes, which was part of a style called musical orientalism. At first, he didn't follow traditional Western music rules. But after he became a professor at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in 1871, he learned a lot about Western music. He spent three years teaching himself and became very skilled in both Russian and Western styles. His music was also inspired by Mikhail Glinka and the composer Richard Wagner.

For most of his life, Rimsky-Korsakov was a composer and a teacher. He also worked in the Russian military. First, he was an officer in the Imperial Russian Navy. Later, he became the civilian Inspector of Naval Bands. He loved the ocean from a young age, which might have inspired his sea-themed works like Sadko and Scheherazade. As Inspector of Naval Bands, he learned a lot about wind and brass instruments. This knowledge made his orchestration even better. He shared this with his students and even wrote a textbook on orchestration.

Rimsky-Korsakov created many original Russian nationalist pieces. He also helped prepare works by other members of The Five for performances. This made their music well-known. He taught many young composers and musicians for decades. Because of this, he is seen as the main person who shaped what people think of as the "Russian style" in classical music. He helped bridge the gap between self-taught composers like Glinka and The Five, and the professionally trained composers who became common in Russia later on. His style influenced many composers, including Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy.

Biography

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov was born in Tikhvin, a town about 200 kilometers (124 miles) east of Saint Petersburg. He came from a noble Russian family. His family had a long history of serving in the Russian government and military.

His father, Andrei Petrovich Rimsky-Korsakov, worked in the government. His mother, Sofya Vasilievna Rimskaya-Korsakova, also came from a noble background.

The Rimsky-Korsakov family often served in the military and navy. Nikolai's older brother, Voin, was 22 years older and a famous explorer. He greatly influenced Nikolai's life. Nikolai remembered that his mother played the piano a little, and his father could play some songs by ear. Nikolai started piano lessons at age six. He was good at hearing music, but he didn't always practice carefully.

Even though he started composing at age 10, Nikolai liked reading more than music. He later wrote that he developed a love for the sea from books and his brother's navy stories. This love led him to join the Imperial Russian Navy at age 12. He studied at a special school in Saint Petersburg and finished his exams in April 1862.

While at school, he took piano lessons from a teacher named Ulikh. His brother Voin, who was then the school director, approved these lessons. He hoped they would help Nikolai become more social. Nikolai said he was "indifferent" to the lessons at first. But he grew to love music after going to operas and concerts.

Ulikh saw Nikolai's musical talent and suggested another teacher, Feodor A. Kanille. Starting in late 1859, Nikolai took piano and composition lessons from Kanille. He later said Kanille inspired him to become a composer. Through Kanille, he discovered new music, including works by Mikhail Glinka and Robert Schumann. When Nikolai turned 17, his brother Voin stopped his music lessons, thinking they were no longer practical.

Kanille told Nikolai to keep visiting him on Sundays to play music and talk. In November 1861, Kanille introduced the 18-year-old Nikolai to Mily Balakirev. Balakirev then introduced him to César Cui and Modest Mussorgsky. All three were composers in their 20s. Nikolai was thrilled to be part of their discussions about music. He felt like he had entered a new world.

Balakirev encouraged Nikolai to compose and taught him basic music rules when he was not at sea. Balakirev also told him to learn about history, literature, and art. When Nikolai showed Balakirev the start of his First Symphony, Balakirev insisted he keep working on it, even though Nikolai had no formal music training.

By late 1862, when Nikolai sailed on a two-year-and-eight-month trip on the ship Almaz, he had finished three parts of his symphony. He composed the slow part while in England and sent it to Balakirev.

At first, working on the symphony kept Nikolai busy during his trip. He bought music scores in every port and even a piano to play them. He also studied Hector Berlioz's book on orchestration. He read books by famous writers like Homer and William Shakespeare. He saw places like London, Niagara Falls, and Rio de Janeiro. But after a while, being away from other musicians made him lose interest. He wrote to Balakirev that he had stopped his music studies for months.

He later remembered, "Thoughts of becoming a musician and composer gradually left me altogether." He felt drawn to distant lands, even though he didn't truly enjoy naval service.

Working with The Five Composers

When Rimsky-Korsakov returned to Saint Petersburg in May 1865, his navy duties were light. But he felt his desire to compose "had been stifled." He said he didn't think about music at all. In September 1865, Balakirev encouraged him to get back into music. Balakirev suggested he write a new part for his symphony and re-orchestrate the whole piece. The symphony was first performed in December 1865.

Letters between Rimsky-Korsakov and Balakirev show that Balakirev often gave ideas for the symphony. Balakirev would even change parts of the music himself.

Rimsky-Korsakov remembered that Balakirev was easy to work with. He gladly rewrote his music based on Balakirev's advice. Even though Rimsky-Korsakov later felt Balakirev's influence was too strong, he still praised Balakirev's skills. With Balakirev's help, Rimsky-Korsakov started other pieces. He began a second symphony but stopped because it sounded too much like Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. He finished an Overture on Three Russian Themes and a Fantasia on Serbian Themes. This Fantasia was played at a concert in 1867. After this concert, the critic Vladimir Stasov called Balakirev's group Moguchaya kuchka, which means "The Mighty Handful" or "The Five." Rimsky-Korsakov also wrote early versions of Sadko and Antar. These works made him known for his orchestral music.

Rimsky-Korsakov spent a lot of time with the other members of The Five. They talked about music, gave feedback on each other's works, and worked together. He became good friends with Alexander Borodin. He also spent more and more time with Mussorgsky. They often played piano music together and discussed other composers. They liked Glinka, Schumann, and Beethoven's later works. They didn't think highly of Mendelssohn, Mozart, or Haydn. Berlioz was highly respected, but Liszt was seen as "crippled." Wagner was rarely discussed. Rimsky-Korsakov listened to these opinions and adopted them. He admitted he often accepted these ideas without fully knowing the music himself.

Within The Five, Rimsky-Korsakov was especially valued for his skill in orchestration. Balakirev asked him to orchestrate a Schubert march. Cui asked him to orchestrate a part of his opera. Even Alexander Dargomyzhsky, a respected older composer, asked him to orchestrate his opera The Stone Guest.

In late 1871, Rimsky-Korsakov moved into his brother Voin's old apartment and invited Mussorgsky to be his roommate. They shared the piano, with Mussorgsky using it in the mornings and Rimsky-Korsakov in the afternoons. They agreed on evening times. Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that they achieved a lot that autumn and winter. Mussorgsky worked on his opera Boris Godunov, and Rimsky-Korsakov worked on his opera Maid of Pskov.

Becoming a Professor and Getting Married

In 1871, at age 27, Rimsky-Korsakov became a Professor of Practical Composition and Orchestration at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. He also led the Orchestra Class. He kept his job in the navy and taught his classes in his military uniform.

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that the new director of the Conservatory, Mikhaíl Azanchevsky, offered him the job with good pay. Some historians think Azanchevsky wanted to bring new ideas to the Conservatory. He might also have wanted to encourage Rimsky-Korsakov to write in a more traditional, Western style. Balakirev, who was against formal music training, still told Rimsky-Korsakov to take the job. He hoped it would help spread nationalist music.

At this time, Rimsky-Korsakov was known for his orchestration in Sadko and Antar. But he had written these works mostly by instinct. He didn't know much about music theory. He had never written counterpoint (combining melodies) and didn't know the names of musical chords. He had also never conducted an orchestra. Knowing his weaknesses, he asked Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky for advice. Tchaikovsky had formal training and was a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. Tchaikovsky told him to study hard.

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that teaching at the Conservatory made him its "very best pupil." To prepare for his classes and stay ahead of his students, he stopped composing new works for three years. He studied textbooks and practiced writing counterpoint, fugues, and choruses.

Rimsky-Korsakov became an excellent teacher and a strong believer in formal training. He revised all his earlier works, including Sadko and Antar, to make them perfect. He also learned to conduct by rehearsing the Orchestra Class. This experience, along with his studies as Inspector of Navy Bands, made him even better at orchestration. His Third Symphony, written after his three years of self-study, shows his improved skills.

Being a professor gave Rimsky-Korsakov financial stability. This encouraged him to marry and start a family. In December 1871, he proposed to Nadezhda Purgold. They had become close at weekly gatherings of The Five. They married in July 1872, with Mussorgsky as the best man. They had seven children. One son, Andrei, became a musicologist and wrote about his father's life.

Nadezhda was also a talented musician. She had studied piano and music theory at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. She became her husband's musical partner and a demanding critic of his work. Her influence on his music was so strong that some wondered if she was leading him away from The Five's musical ideas. Musicologist Lyle Neff wrote that Nadezhda stopped her own composing career after marriage. But she greatly influenced her husband's first three operas. She traveled with him, attended rehearsals, and arranged his music for piano. Later in life, she worked to publish his writings and music.

In early 1873, the navy created a new civilian job: Inspector of Naval Bands. Rimsky-Korsakov was appointed to this role. This kept him on the navy payroll but allowed him to leave his military commission. He wrote that he was delighted to leave his military status and uniform. He was now officially a musician. As Inspector, he worked very hard. He visited navy bands across Russia, checked on bandmasters, reviewed their music, and inspected their instruments. He also created a study program for music students with navy scholarships. He learned a lot about how orchestral instruments are built and played. These studies led him to write a textbook on orchestration. He used his position to learn and share his knowledge. He discussed music arrangements with bandmasters and orchestrated works for military bands.

In March 1884, the navy abolished the Inspector of Bands office, and Rimsky-Korsakov lost his job. He then worked as a deputy under Balakirev at the Court Chapel until 1894. This allowed him to study Russian Orthodox church music. He also taught classes there and wrote his textbook on harmony.

Creative Challenges and New Directions

Rimsky-Korsakov's intense studies and his new views on music education made some of his fellow nationalist composers upset. They thought he was abandoning his Russian roots to write complex music like fugues and sonatas. After he tried to put "as much counterpoint as possible" into his Third Symphony, he wrote chamber works that followed classical rules. These included a string sextet and a string quartet. Tchaikovsky wrote that these works were "filled with a host of clever things but... imbued with a dryly pedantic character." Borodin joked that the symphony sounded like a "German Herr Professor."

Rimsky-Korsakov said that the other members of The Five were not enthusiastic about his symphony or quartet. His first public performance as a conductor in 1874, where he led his new symphony, was also not well-received by his friends. He felt they started to look down on him. Even worse, Anton Rubinstein, a composer who disliked nationalist music, gave him faint praise. Rubinstein said that after hearing the quartet, Rimsky-Korsakov "might amount to something" as a composer. Tchaikovsky, however, continued to support him. He told Rimsky-Korsakov that he admired his artistic modesty and strength. Privately, Tchaikovsky wondered if Rimsky-Korsakov would become a great master or get stuck in "contrapuntal tricks."

Two projects helped Rimsky-Korsakov focus on less academic music. First, he created two collections of folk songs in 1874. He wrote down 40 Russian songs for voice and piano from a folk singer. Then he made a second collection of 100 songs from friends and old books. Rimsky-Korsakov later said this work greatly influenced him as a composer. It also gave him many musical ideas for future projects. The second project was editing the orchestral scores of the pioneering Russian composer Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857). He worked with Balakirev and Anatoly Lyadov. Glinka's sister wanted to publish her brother's music and paid for the project. This was a new type of project in Russian music, and they had to create rules for editing. Balakirev wanted to change Glinka's music to "correct" flaws. But Rimsky-Korsakov wanted to make fewer changes. Rimsky-Korsakov's approach won. He wrote that working on Glinka's scores was a great learning experience. It led him back to modern music after his focus on strict counterpoint.

In mid-1877, Rimsky-Korsakov became very interested in the short story May Night by Nikolai Gogol. He and his wife Nadezhda had read it together. She encouraged him to write an opera based on it. Musical ideas for the opera came to him more often. By early 1878, he started writing seriously and finished the opera by November.

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that May Night was very important because it helped him "cast off the shackles of counterpoint." He wrote the opera with folk-like melodies and a clear, simple style, similar to Glinka. Even so, despite the ease of writing this opera and his next, The Snow Maiden, he sometimes struggled to compose between 1881 and 1888. During this time, he stayed busy by editing Mussorgsky's works and finishing Borodin's Prince Igor (Mussorgsky died in 1881, Borodin in 1887).

The Belyayev Circle

Rimsky-Korsakov met the music supporter Mitrofan Belyayev in Moscow in 1882. Belyayev was a wealthy industrialist who supported the arts in Russia. Like other rich patrons, he wanted to help public life and believed in Russia's greatness. They preferred to support Russian artists over foreign ones. This fit with a growing sense of nationalism in Russian art and society.

By 1883, Rimsky-Korsakov regularly attended weekly music gatherings at Belyayev's home in Saint Petersburg. Belyayev was very interested in the young composer Alexander Glazunov. In 1884, Belyayev rented a hall and hired an orchestra to play Glazunov's First Symphony. This concert gave Rimsky-Korsakov the idea to offer concerts featuring Russian music, and Belyayev agreed. The Russian Symphony Concerts started in 1886–87. Rimsky-Korsakov shared conducting duties with Anatoly Lyadov. He finished his revision of Mussorgsky's Night on Bald Mountain and conducted it at the first concert. These concerts also helped him overcome his creative block. He wrote Scheherazade, Capriccio Espagnol, and the Russian Easter Overture specifically for these concerts. He noted that these three works used less counterpoint and more complex musical patterns.

Rimsky-Korsakov became the leader of the Belyayev circle. Belyayev asked him for advice on the concerts and other projects. In 1884, Belyayev started an annual Glinka prize. In 1885, he founded his own music publishing company. He published works by Borodin, Glazunov, Lyadov, and Rimsky-Korsakov at his own expense. To choose which composers to help, Belyayev set up a council with Glazunov, Lyadov, and Rimsky-Korsakov. They would review submissions and suggest who deserved support.

The composers who gathered with Glazunov, Lyadov, and Rimsky-Korsakov became known as the Belyayev circle. Like The Five, these composers believed in a unique Russian style of classical music. They used folk music and exotic sounds, like Balakirev, Borodin, and Rimsky-Korsakov did. But unlike The Five, these composers also believed in the importance of formal, Western-based music training. Rimsky-Korsakov had taught this at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. Rimsky-Korsakov found the Belyayev circle composers to be "progressive." They valued technical skill but also explored new paths more carefully.

Growing Closer to Tchaikovsky

In November 1887, Tchaikovsky came to Saint Petersburg to hear some of the Russian Symphony Concerts. One concert featured the first full performance of his First Symphony. Another had the premiere of Rimsky-Korsakov's revised Third Symphony. Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky had written to each other before this visit. They spent a lot of time together with Glazunov and Lyadov. Tchaikovsky had visited Rimsky-Korsakov's home since 1876. This visit marked the beginning of a closer relationship between them. Within a few years, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that Tchaikovsky's visits became more frequent.

In public, Rimsky-Korsakov seemed friendly. But privately, he found the situation difficult. He told his friend Semyon Kruglikov about his worries. He remembered the tension between Tchaikovsky and The Five because of their different musical ideas. Tchaikovsky's brother even compared their relationship to "two friendly neighboring states... cautiously prepared to meet on common ground, but jealously guarding their separate interests." Rimsky-Korsakov noticed, with some annoyance, that Tchaikovsky was becoming more popular among his own followers. This personal jealousy was made worse by professional jealousy, as Tchaikovsky's music became more famous than his own. Even so, when Tchaikovsky attended Rimsky-Korsakov's nameday party in May 1893, Rimsky-Korsakov asked him to conduct four concerts for the Russian Musical Society in Saint Petersburg the next season. Tchaikovsky agreed. His sudden death in late 1893 prevented him from fulfilling this. But the list of works he planned to conduct included Rimsky-Korsakov's Third Symphony.

Later Years and the 1905 Revolution

In March 1889, Angelo Neumann's traveling "Richard Wagner Theater" came to Saint Petersburg. They performed Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen. The Five had ignored Wagner's music, but The Ring deeply impressed Rimsky-Korsakov. He was amazed by Wagner's skill in orchestration. He attended rehearsals with Glazunov and studied the music. After these performances, Rimsky-Korsakov focused mostly on composing operas for the rest of his life. Wagner's use of the orchestra influenced Rimsky-Korsakov's own orchestration.

However, Rimsky-Korsakov did not like music that was more experimental than Wagner's, especially by composers like Richard Strauss and Claude Debussy. He would get angry after hearing Debussy's music, calling it "poor and skimpy." This was part of his growing musical conservatism. He became very critical of his own music and others'. While working on his first revision of Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov in 1895, he told his assistant, "It's incredible that I ever could have liked this music." By 1901, he wrote about being "indignant at all [of Wagner's] blunders"—even though Wagner's music had impressed him earlier.

In 1892, Rimsky-Korsakov experienced a second period where he struggled to compose. He suffered from depression and physical symptoms like memory loss. Doctors diagnosed him with neurasthenia. Problems in his family also played a part. His wife and a son were seriously ill, and his mother and youngest child died. He resigned from the Russian Symphony Concerts and the Court Chapel. He even thought about stopping composition forever. After making third versions of Sadko and The Maid of Pskov, he decided to move on from his past works. He had changed all his major works written before May Night.

Another death helped him start composing again. Tchaikovsky's passing gave him two opportunities: to write for the Imperial Theaters and to compose an opera based on Nikolai Gogol's short story Christmas Eve. Tchaikovsky had also based an opera on this story. The success of Rimsky-Korsakov's Christmas Eve encouraged him. He completed an opera about every 18 months between 1893 and 1908, totaling 11 operas. He also started and almost finished a third version of his textbook on orchestration in his last four years. His son-in-law Maximilian Steinberg completed the book in 1912. Rimsky-Korsakov's detailed book on orchestration, with over 300 examples from his work, set a new standard.

In 1905, protests happened at the St. Petersburg Conservatory as part of the 1905 Revolution. Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that these protests were sparked by similar events at St. Petersburg State University. Students demanded political changes and a constitutional monarchy.

Rimsky-Korsakov, who was always politically liberal, felt someone needed to protect the students' right to protest. The disputes between students and authorities were becoming violent. In an open letter, he supported the students against what he saw as unfair interference by the Conservatory leadership. A second letter, signed by Rimsky-Korsakov and other faculty, demanded the resignation of the Conservatory head. Because of these letters, about 100 Conservatory students were expelled, and Rimsky-Korsakov was removed from his professorship.

Just before his dismissal, Rimsky-Korsakov received a letter suggesting he take over as director to calm the student unrest. He refused. Partly to defy his dismissal, Rimsky-Korsakov continued teaching his students at his home.

Soon after his dismissal, a student performance of his opera Kashchey the Immortal turned into a political protest. This led to a police ban on Rimsky-Korsakov's works. News of these events spread widely, causing outrage across Russia and abroad. People sent the composer letters of sympathy, and even peasants sent small donations. Several faculty members, including Glazunov and Lyadov, resigned in protest. Over 300 students left the Conservatory to support Rimsky-Korsakov. By December, he was reinstated under a new director, Glazunov. Rimsky-Korsakov retired from the Conservatory in 1906. The political controversy continued with his opera The Golden Cockerel. Its implied criticism of monarchy and the Russo-Japanese War meant it had little chance of passing the censors. The premiere was delayed until 1909, after Rimsky-Korsakov's death. Even then, it was performed in an adapted version.

In April 1907, Rimsky-Korsakov conducted two concerts in Paris. These concerts, organized by Sergei Diaghilev, featured Russian nationalist music. They were very successful in making Russian classical music popular in Europe. The next year, his opera Sadko was performed at the Paris Opéra, and The Snow Maiden at the Opéra-Comique. He also heard more recent European music. He disliked Richard Strauss's opera Salome. After hearing Claude Debussy's opera Pelléas et Mélisande, he told Diaghilev, "Don't make me listen to all these horrors or I shall end up liking them!" Hearing these works helped him understand his place in classical music. He admitted that he was a "convinced kuchkist" (a member of The Five) and that his works belonged to an older musical era.

Death

Around 1890, Rimsky-Korsakov began suffering from angina, a heart condition. The stress from the 1905 Revolution made his illness much worse. After December 1907, he became severely ill and could no longer work.

In 1908, he died at his estate near Luga. He was buried in Tikhvin Cemetery in the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg, next to Borodin, Glinka, Mussorgsky, and Stasov.

Compositions

Rimsky-Korsakov followed the musical ideas of The Five. He used Orthodox church themes in the Russian Easter Festival Overture. He used folk songs in Capriccio Espagnol and exotic sounds in Scheherazade, which is probably his most famous work. He wrote a lot of music but was always critical of his own work. He revised every orchestral piece up to his Third Symphony, some more than once. These changes ranged from small adjustments to complete rewrites.

Rimsky-Korsakov was open about his musical influences. He told his assistant, "Study Liszt and Balakirev more closely, and you'll see that a great deal in me is not mine." He followed Balakirev in using the whole tone scale, folk songs, and musical orientalism. He followed Liszt for adventurous harmonies. For example, the violin tune for Scheherazade is similar to a theme in Balakirev's Tamara. The Russian Easter Overture also follows Balakirev's style.

However, his use of whole tone and octatonic scales showed his originality. He used these musical devices for the "fantastic" parts of his operas. These parts showed magical or supernatural characters and events.

Rimsky-Korsakov remained interested in musical experiments throughout his career. But he always controlled his experiments, avoiding too much excess. The more unusual his harmonies became, the more he tried to control them with strict rules. In this way, he was both a progressive and a conservative composer. His use of whole tone and octatonic scales was daring for Western classical music. But his careful use of them made him seem conservative compared to later composers like Igor Stravinsky, who often built on Rimsky-Korsakov's work.

Operas

While Rimsky-Korsakov is best known in the West for his orchestral works, his operas are more complex. They offer a wider range of orchestral sounds and beautiful singing. Parts of his operas are as popular as his purely orchestral works. The most famous excerpt is probably "Flight of the Bumblebee" from The Tale of Tsar Saltan. This piece is often played by itself and has been arranged many times, most famously for piano by Sergei Rachmaninoff. Other well-known pieces include "Dance of the Tumblers" from The Snow Maiden and "Procession of the Nobles" from Mlada.

His operas fall into three main types:

- Historical dramas: These include The Maid of Pskov, Mozart and Salieri, and The Tsar's Bride.

- Folk operas: Examples are May Night and Christmas Eve.

- Fairy tales and legends: These include The Snow Maiden, Sadko, The Tale of Tsar Saltan, and The Golden Cockerel.

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote in 1902, "In every new work of mine I am trying to do something that is new for me." He wanted his music to stay fresh and interesting.

American music critic Harold C. Schonberg wrote that the operas "open up a delightful new world." This world is full of Russian Eastern themes, magic, and ancient Slavic beliefs. They are full of poetry and are brilliantly orchestrated. Some critics say Rimsky-Korsakov's operas lack strong drama. But he often said that operas were first and foremost musical works, not just dramatic ones.

Orchestral Works

Rimsky-Korsakov's purely orchestral works are of two types. The most famous ones in the West are mostly programmatic. This means their music tells a story or describes characters or events. The second type of works is more academic, like his First and Third Symphonies. In these, he still used folk themes but applied strict musical rules to them.

Program music came naturally to Rimsky-Korsakov. He believed "even a folk theme has a program of sorts." He composed most of his orchestral works in this style during two periods. First, at the beginning of his career, with Sadko and Antar. Second, in the 1880s, with Scheherazade, Capriccio Espagnol, and the Russian Easter Overture. His approach to musical themes stayed consistent between these periods. Both Antar and Scheherazade use a strong "Russian" theme for the male characters and a more flowing "Eastern" theme for the female ones.

Where Rimsky-Korsakov changed was in his orchestration. His pieces were always known for their imaginative use of instruments. But the earlier works like Sadko and Antar had simpler sounds compared to the rich sounds of his popular works from the 1880s. He focused on clear instrumental colors. In his later works, he added complex orchestral effects. Some he learned from other composers like Wagner, but many he invented himself.

As a result, his later works sound like brightly colored mosaics. They are striking and often use pure groups of instruments side by side. The final part of Scheherazade is a great example. The main tune is played by trombones together. It is joined by patterns in the strings. Meanwhile, other patterns alternate with scales in the woodwinds, and rhythms are played by percussion.

Rimsky-Korsakov's non-program music, though well-made, is not as inspiring as his programmatic works. He needed fantasy to bring out his best. The First Symphony closely follows Schumann's Fourth. The Third Symphony and Sinfonietta contain variations that can sometimes feel repetitive.

Smaller Works

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote many art songs, folk song arrangements, and chamber and piano music. While his piano music is not as important, many of his art songs are beautifully delicate. They are a standard part of Russian singers' performances.

He also wrote choral works, both for general use and for the Russian Orthodox Church. This included settings of parts of the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, even though he was an atheist.

Legacy

A Bridge Between Musical Styles

The critic Vladimir Stasov, who helped start The Five, wrote in 1882 that Russian musicians were skeptical of formal music education. This was true for Balakirev, who strongly opposed academic training. It was also true for Rimsky-Korsakov at first.

Stasov left out an important point: by the time he wrote this, Rimsky-Korsakov had been teaching formal music theory at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory for over ten years. After his three years of self-study, Rimsky-Korsakov grew closer to Tchaikovsky and further from the rest of The Five. Stasov even called him a "renegade." Music historian Richard Taruskin wrote that Rimsky-Korsakov looked back on his early days with The Five with increasing irony.

Taruskin points out that Rimsky-Korsakov's statement, written while Borodin and Mussorgsky were still alive, shows his distance from The Five. It also shows the kind of teacher he became. By the time he taught Liadov and Glazunov, their training was very similar to Tchaikovsky's. They were taught to be very professional from the start. By the time Borodin died in 1887, the era of self-taught Russian composers had largely ended. Every Russian who wanted to write classical music went to a conservatory and received formal education. Taruskin writes that "at last all Russia was one." By the end of the century, the music theory and composition departments at Rubinstein's Conservatory were run by people from the New Russian School.

His Students

Rimsky-Korsakov taught theory and composition to 250 students during his 35 years at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. This doesn't include students he taught at other schools, like Glazunov, or privately at his home, like Igor Stravinsky. Besides Glazunov and Stravinsky, other famous students included Anatoly Lyadov, Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov, Sergei Prokofiev, and Ottorino Respighi.

Rimsky-Korsakov believed talented students didn't need much strict instruction. His teaching method involved showing students what they needed to know in harmony and counterpoint. He guided them in understanding musical forms. He gave them a year or two of systematic study in technique, free composition, and orchestration. He also made sure they knew the piano well. Once these steps were done, their studies would be complete. Conductor Nikolai Malko remembered that Rimsky-Korsakov started his first class by saying, "I will speak, and you will listen. Then I will speak less, and you will start to work. And finally I will not speak at all, and you will work." Malko said his class followed this pattern exactly. Rimsky-Korsakov explained everything so clearly that students just had to do their work well.

Editing Works of The Five

Rimsky-Korsakov's work in editing the compositions of The Five was very important. It was like an extension of how they worked together in the 1860s and 1870s. They would listen to each other's music and work on it together. His editing helped save works that might otherwise have been lost or never performed. This included finishing Alexander Borodin's opera Prince Igor with the help of Glazunov after Borodin's death. He also orchestrated parts of César Cui's William Ratcliff for its first performance. He fully orchestrated the opera The Stone Guest by Alexander Dargomyzhsky three times. Dargomyzhsky was not a member of The Five but shared their musical ideas.

Musicologist Francis Maes wrote that while Rimsky-Korsakov's efforts were good, they were also debated. For Prince Igor, it was thought that Rimsky-Korsakov edited and orchestrated existing parts, while Glazunov composed missing parts, like most of the third act and the overture. This is what Rimsky-Korsakov stated. But Maes and Richard Taruskin point to an analysis of Borodin's notes by Pavel Lamm. This analysis showed that Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazunov removed almost 20 percent of Borodin's original music. Maes says the result is more a joint effort by all three composers than a true representation of Borodin's original idea. Lamm noted that Borodin's notes were so messy that creating a modern version without Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazunov's changes would be very difficult.

More controversial, according to Maes, was Rimsky-Korsakov's editing of Mussorgsky's works. After Mussorgsky died in 1881, Rimsky-Korsakov revised and completed several of his works for publication and performance. This helped spread Mussorgsky's music. Maes wrote that Rimsky-Korsakov let his "musical conscience" guide his editing. He changed or removed what he thought were musical experiments or poor forms. Because of this, Rimsky-Korsakov has been criticized for "correcting" things like harmony.

Maes stated that over time, Rimsky-Korsakov's judgment was proven right in some ways. Mussorgsky's musical style, once seen as rough, is now admired for its originality. While Rimsky-Korsakov's arrangement of Night on Bald Mountain is still usually performed, his other revisions, like his version of Boris Godunov, have been replaced by Mussorgsky's original versions.

Folklore and Nature Themes

Rimsky-Korsakov often used Russian folklore in his music. Other composers in The Five used a type of folk dance song called protyazhnaya. This song style has flexible rhythms, uneven phrases, and unclear tones. After composing May Night, Rimsky-Korsakov became more interested in "calendar songs." These songs were for specific traditional events. He was most interested in how folk music connected to folk culture. These songs were part of rural customs and echoed old Slavic paganism and the idea of pantheism (worshipping nature) in folk rituals. Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that his interest in these songs grew when he studied them for his folk song collections. He was "captivated by the poetic side of the cult of sun-worship." He felt like he could see the ancient pagan period clearly, which greatly influenced his work as a composer.

Rimsky-Korsakov's interest in nature worship was sparked by the folklore studies of Alexander Afanasyev. Afanasyev's book, The Poetic Outlook on Nature by the Slavs, became very important to Rimsky-Korsakov. The composer first used Afanasyev's ideas in May Night. He added folk dances and calendar songs to Gogol's story. He went even further in The Snow Maiden, using many seasonal calendar songs and khorovodi (ceremonial dances) from folk traditions.

Music experts have noted that Rimsky-Korsakov was an artist who explored many ideas. His folklore-inspired operas often dealt with topics like the connection between paganism and Christianity.

In Film

- The 1953 Soviet film Rimsky-Korsakov shows the last twenty years of his life. He is played by Grigori Belov. His earlier years with The Five were shown in the 1950 film Mussorgsky, where he was played by Andrei Popov.

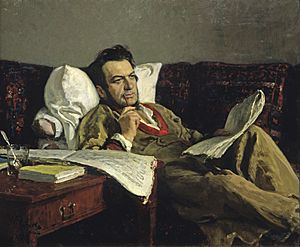

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Nikolái Rimski-Kórsakov para niños

In Spanish: Nikolái Rimski-Kórsakov para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |