Anton Rubinstein facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Anton Rubinstein

|

|

|---|---|

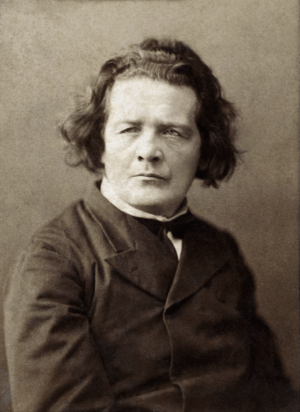

Portrait of Rubinstein by Ilya Repin

|

|

| Born |

Anton Grigoryevich Rubinstein

28 November [O.S. 16 November] 1829 Vikhvatinets, Baltsky Uyezd, Podolia Governorate, Russian Empire

|

| Died | 20 November [O.S. 8 November] 1894 (aged 64) Petergof, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire

|

| Occupation | Pianist, teacher, composer and conductor |

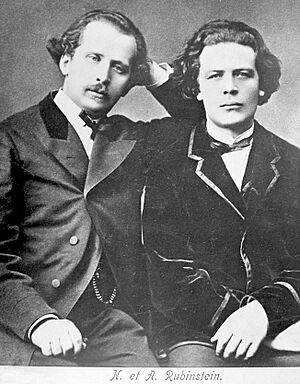

Anton Grigoryevich Rubinstein (Russian: Антон Григорьевич Рубинштейн, tr. Anton Grigor'evič Rubinštejn; 28 November [O.S. 16 November] 1829 – 20 November [O.S. 8 November] 1894) was a famous Russian pianist, composer, and conductor. He played a very important role in Russian culture when he started the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, a major music school. He was the older brother of Nikolai Rubinstein, who also founded another important music school, the Moscow Conservatory.

As a pianist, Rubinstein was one of the greatest keyboard players of the 1800s. He was especially known for his "historical recitals." These were seven huge concerts in a row that showed the history of piano music. Rubinstein performed these special concerts across Russia, Eastern Europe, and the United States.

Even though he is best remembered as a pianist and teacher (he taught Tchaikovsky composition), Rubinstein also wrote a lot of music. He composed 20 operas, with The Demon being the most famous. He also wrote many other pieces, including five piano concertos, six symphonies, and many works for solo piano and chamber groups.

Contents

Early Life and Music Training

Anton Rubinstein was born in a village called Vikhvatinets in the Russian Empire. His family was Jewish, but before he turned five, his grandfather decided that all family members should become Russian Orthodox. So, Anton was raised as a Christian.

His mother, who was a good musician, started teaching him piano when he was five. Later, a teacher named Alexander Villoing heard him play and took Rubinstein as a student for free. Rubinstein played his first public concert at age nine. That same year, his mother sent him with Villoing to Paris. He tried to join the famous Paris Conservatoire but wasn't accepted.

Rubinstein and Villoing stayed in Paris for a year. In December 1840, Rubinstein played for an audience that included famous composers like Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt. Chopin invited Rubinstein to his studio and played for him. Liszt suggested that Villoing take Rubinstein to Germany to study composing. However, Villoing took Rubinstein on a long concert tour across Europe and Western Russia instead. They finally returned to Moscow in June 1843.

To help Anton and his younger brother Nikolai with their music careers, their mother sent them on a tour of Russia. After this, the brothers went to Saint Petersburg to play for Tsar Nicholas I and the royal family at the Winter Palace. Anton was 14 years old, and Nikolai was eight.

Travels and Performances

Studying in Berlin

In the spring of 1844, Rubinstein, Nikolai, their mother, and sister Luba traveled to Berlin. There, Anton met and received support from famous composers like Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer.

Mendelssohn, who had heard Rubinstein play before, said he didn't need more piano lessons. Meyerbeer sent both Anton and Nikolai to Siegfried Dehn to study composition and music theory.

In 1846, Rubinstein's father became very ill. Anton stayed in Berlin while his mother, sister, and brother went back to Russia. He continued his studies and started composing seriously. By then, he was 17 and no longer a child prodigy. He visited Liszt in Vienna, hoping to become his student. But Liszt told him that a talented person must succeed on their own. Rubinstein faced hard times and poverty. After an unsuccessful year in Vienna and a concert tour in Hungary, he returned to Berlin and gave music lessons.

Returning to Russia

The Revolution of 1848 forced Rubinstein to return to Russia. For the next five years, he mostly stayed in Saint Petersburg. He taught, gave concerts, and often performed for the Imperial court. The Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, the Tsar's sister-in-law, became his most important supporter. By 1852, he was a leading musician in Saint Petersburg. He performed as a soloist and worked with many great musicians who visited the city.

He also composed a lot of music. After some delays, his first opera, Dmitry Donskoy, was performed in Saint Petersburg in 1852. Three more short operas followed. He also played and conducted several of his own works, including his Ocean Symphony and his Second Piano Concerto. Because his operas weren't very successful in Russia, Rubinstein decided to travel abroad again to become more famous as a serious artist.

Touring Europe Again

In 1854, Rubinstein started a four-year concert tour of Europe. This was his first big tour in ten years. Now 24, he felt ready to show the public his skills as a pianist and a composer. He quickly became known again as a great virtuoso. Many people, like Ignaz Moscheles, said he was as powerful and skilled as anyone.

Rubinstein often played his own compositions during his concerts. At some shows, he would conduct his orchestral works and then play as a soloist in one of his piano concertos. A special moment was when he conducted his Ocean Symphony in Leipzig in 1854. While opinions on his composing were mixed, people loved his piano playing.

During a break from touring in 1856–57, Rubinstein stayed with Elena Pavlovna and the royal family in Nice. He discussed with Elena Pavlovna plans to improve music education in Russia. These talks led to the creation of the Russian Musical Society (RMS) in 1859.

Founding the St. Petersburg Conservatory

The Saint Petersburg Conservatory, Russia's first music school, opened in 1862. It grew out of the Russian Musical Society. Rubinstein not only founded the school and became its first director, but he also brought in many talented teachers.

Some people in Russia were surprised that a Russian music school would try to be truly Russian. Others worried it wouldn't be Russian enough. Rubinstein faced a lot of criticism from a group of Russian nationalist composers known as The Five.

During this time, Rubinstein had his greatest success as a composer. This included his Fourth Piano Concerto in 1864 and his opera The Demon in 1871. He also wrote orchestral works like Don Quixote, which Tchaikovsky liked.

American Tour

By 1867, disagreements with the "The Five" group and other issues caused problems within the Conservatory. Rubinstein resigned and went back to touring Europe. Unlike his earlier tours, he started playing more works by other composers instead of just his own.

The Steinway & Sons piano company asked Rubinstein to tour the United States in 1872–73. His contract with Steinway was for 200 concerts at a very high rate of 200 dollars per concert, plus all expenses. Rubinstein stayed in America for 239 days and gave 215 concerts. Sometimes he played two or three concerts a day in different cities!

Even though he found the tour difficult, Rubinstein earned enough money to be financially secure for the rest of his life. When he returned to Russia, he bought a country house (dacha) in Peterhof, near Saint Petersburg, for himself and his family.

Later Life

Rubinstein continued to tour as a pianist and conduct orchestras. In 1887, he returned to the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. He wanted to improve the school's standards. He removed weaker students, changed many professors' roles, made entrance and exam rules stricter, and updated the courses. He also taught special classes for teachers and gave personal coaching to talented piano students.

He resigned again in 1891 and left Russia. This was because the government wanted to set limits on how many students from certain ethnic groups could be admitted or receive awards, which would unfairly affect Jewish students. Rubinstein moved to Dresden and started giving concerts again in Germany and Austria. Most of these concerts were for charity.

Rubinstein also coached a few pianists, including his only private piano student, Josef Hofmann. Hofmann became one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century.

Despite his feelings about the ethnic policies in Russia, Rubinstein sometimes returned to visit friends and family. He gave his last concert in Saint Petersburg on January 14, 1894. His health quickly declined, and he moved back to Peterhof in the summer of 1894. He died there on November 20 of that year from heart disease.

Today, a street in Saint Petersburg where he lived is named Rubinstein Street in his honor.

Rubinstein's Piano Playing

"Van II"

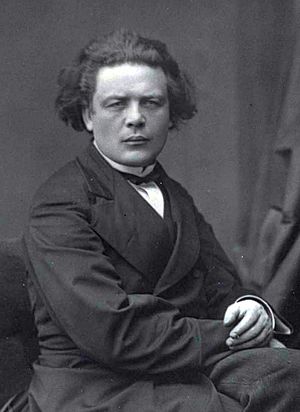

Many people at the time thought Rubinstein looked a lot like Ludwig van Beethoven. Ignaz Moscheles, who knew Beethoven well, said Rubinstein's face and hair reminded him of Beethoven. Liszt even called Rubinstein "Van II." People also felt his piano playing was like Beethoven's. They said the piano would "erupt volcanically" when he played. Audiences often felt exhausted after his concerts, feeling like they had witnessed a powerful force.

Sometimes Rubinstein's playing was too intense for listeners. American pianist Amy Fay wrote that while he had a "gigantic spirit" and was "poetic and original," an entire evening of his playing was "too much." She once got a terrible headache from his performance of a Schubert piece.

Clara Schumann, another famous pianist, was very critical. After hearing him play a Mendelssohn trio, she wrote that he played it so fast and loudly that she couldn't hear the other instruments. She later said he "no longer plays" but just made "a perfectly wild noise or else a whisper."

Viennese music critic Eduard Hanslick wrote in 1884 that Rubinstein's playing had a "natural strength and elemental freshness." He concluded, "Yes, he plays like a god, and we do not take it amiss if, from time to time, he changes, like Jupiter, into a bull." Rubinstein was also very good at improvising music on the spot, a skill Beethoven also had.

His Technique

Rubinstein's teacher, Villoing, helped him with hand position and finger skills. From watching Liszt, Rubinstein learned how to move his arms freely. Theodor Leschetizky, a piano teacher at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, compared muscle relaxation at the piano to a singer's deep breathing. He noted how Rubinstein would take "deep breaths" at the start of long musical phrases and use dramatic pauses.

In his book The Great Pianists, music critic Harold C. Schonberg described Rubinstein's playing as "extraordinary breadth, virility and vitality." He said it had "immense sonority and technical grandeur," but sometimes it could be a bit messy. When he was really into a performance, Rubinstein didn't seem to mind if he played some wrong notes, as long as he expressed the music's feeling. He once joked, "If I could gather up all the notes that I let fall under the piano, I could give a second concert with them."

Part of the reason for this might have been the size of Rubinstein's hands. They were huge! Josef Hofmann, his student, said Rubinstein's fifth finger was "as thick as my thumb." Pianist Josef Lhévinne described them as "fat, pudgy" with fingertips so broad that he sometimes hit two notes at once.

Because of these occasional messy moments, some more precise pianists questioned Rubinstein's greatness. But those who valued the feeling and interpretation of the music more than perfect technique praised him highly. Pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow called Rubinstein "the Michelangelo of music."

Sound Quality

Many people said Rubinstein's piano playing had a beautiful, singing quality. His sound was "strikingly full and deep." They said that when he played, the piano sounded like a whole orchestra, not just in terms of power but also in the variety of sounds.

Schonberg believed Rubinstein had the most expressive piano sound of any great pianist. Another pianist, Rafael Joseffy, compared it to "a golden French horn." Rubinstein himself said, "Strength with lightness, that is one secret of my touch." He also said he spent hours trying to make his piano sound like the voice of a famous singer, Rubini.

Rubinstein told a young Rachmaninoff how he got his special sound: "Just press upon the keys until the blood oozes from your fingertips." When he wanted to, Rubinstein could play very lightly and delicately. However, he usually played powerfully because he knew audiences loved to hear him "thunder." His strong playing made a huge impression during his American tour, where such powerful piano playing had never been heard before.

Concert Programs

Rubinstein's concert programs were often very long. Hanslick mentioned that in one concert in Vienna, Rubinstein played more than 20 pieces, including three long sonatas by Schumann and Beethoven. Rubinstein was a very strong person and seemed never to get tired. Audiences seemed to give him extra energy, making him perform like a "superman." He knew a huge amount of music by heart until he turned 50, when he started having memory lapses and had to use sheet music.

Rubinstein was most famous for his "historical recitals." These were seven concerts in a row that showed the history of piano music. Each program was enormous. For example, the second concert, dedicated to Beethoven sonatas, included eight famous sonatas like the Moonlight, Appassionata, and Op. 111. All of these were played in one recital! The fourth concert, focused on Schumann, included major works like the Fantasy in C and Carnaval. This doesn't even count the many extra pieces Rubinstein would play as encores.

Rubinstein ended his American tour with this series, playing all seven recitals over nine days in New York City in May 1873. He also performed this series in Russia and Eastern Europe. In Moscow, he gave the series on Tuesday evenings and repeated each concert the next morning for students, free of charge.

Rachmaninoff's Thoughts on Rubinstein

Sergei Rachmaninoff first attended Rubinstein's historical concerts when he was a twelve-year-old piano student. Years later, he said that Rubinstein's playing "gripped my whole imagination" and greatly influenced his own goals as a pianist.

Rachmaninoff explained that it wasn't just Rubinstein's amazing technique that captivated people. It was his "profound, spiritually refined musicianship" that came through every note. This made him "the most original and unequalled pianist in the world."

Rachmaninoff remembered that Rubinstein wasn't always perfect at these concerts. He recalled a time when Rubinstein forgot a part during Balakirev's Islamey. Rubinstein simply improvised in the style of the piece until he remembered the rest of it four minutes later. Rachmaninoff defended him, saying that "for every possible mistake [Rubinstein] may have made, he gave, in return, ideas and musical tone pictures that would have made up for a million mistakes."

Conducting

Rubinstein conducted the Russian Musical Society programs from its start in 1859 until he resigned in 1867. He also conducted as a guest before and after his time with the RMS. When Rubinstein was on the podium, he was as passionate as he was at the piano. This led to mixed reactions from both orchestra musicians and audiences.

Teacher

As a composition teacher, Rubinstein was very inspiring. He was known for spending a lot of time and effort with his students, even after a long day of administrative work. He also had high expectations for them. According to one of Tchaikovsky's fellow students, Rubinstein would sometimes start class by reading some verses and then ask students to set them to music for a singer or a chorus. This assignment would be due the next day. Other times, he would expect students to create a minuet, a rondo, or another musical form on the spot.

Rubinstein constantly told his students not to be timid. He advised them not to stop at a difficult part in a piece but to keep going. He also encouraged them to write down their musical ideas in sketches and to avoid composing only at the piano. Famous students he taught include pianists Josef Hofmann and Sandra Drouker.

Compositions

By 1850, Rubinstein decided he wanted to be known not just as a pianist, but as a composer who performed his own symphonies, concertos, and operas. Rubinstein wrote a lot of music. He composed at least twenty operas, including the well-known The Demon and The Merchant Kalashnikov. He also wrote five piano concertos, six symphonies, and many pieces for solo piano. He also wrote a lot of music for chamber groups, two concertos for cello, one for violin, and orchestral works like Don Quixote.

Rubinstein's music doesn't show the strong Russian national style found in the music of The Five. Instead, his music was more influenced by German composers like Robert Schumann and Felix Mendelssohn. Rubinstein also tended to compose quickly, which sometimes meant that good ideas, like those in his Ocean Symphony, weren't always developed in the best way.

After Rubinstein's death, his works became less popular. However, his piano concertos were still played in Europe until World War I. His main works have also kept a place in Russian concert halls. His music might have lacked a unique sound compared to the established classics or the new Russian styles of Stravinsky and Prokofiev.

In recent years, his music has been performed more often in Russia and other countries, often receiving good reviews. Among his most famous works are the opera The Demon, his Piano Concerto No. 4, and his Symphony No. 2, known as The Ocean.

Rubinstein's Clever Sayings

Rubinstein was known for his sharp wit and sometimes very insightful comments. During one of his visits to Paris, French pianist Alfred Cortot played the first movement of Beethoven's Appassionata for him. After a long silence, Rubinstein told Cortot, "My boy, never forget what I am going to tell you. Beethoven's music must not be studied. It must be reincarnated." Cortot reportedly never forgot those words.

Rubinstein's own piano students were also challenged. He wanted them to think about the music they were playing and match the sound to the piece. His way of teaching combined strong, sometimes harsh criticism with good humor.

Rubinstein insisted that his students play exactly what was written in the music. This surprised Josef Hofmann, because he had heard his teacher take liberties in his own concerts. When Hofmann asked Rubinstein about this, Rubinstein replied, "When you are as old as I am, you may do as I do." Then he added, "If you can."

Rubinstein also didn't hold back his comments, even for important people. When he returned to lead the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, Tsar Alexander III gave the old, run-down Bolshoi Theater as the Conservatory's new home. However, he didn't provide money to fix it up. At a party for the Tsar, the Tsar asked Rubinstein if he was happy with the gift. Rubinstein replied bluntly, to everyone's shock, "Your Imperial Majesty, if I gave you a beautiful cannon, all mounted and embossed, with no ammunition, would you like it?"

Rubinstein's Voice Recording

A recording of Anton Rubinstein's voice was made in Moscow in January 1890. He is heard making a positive comment about the phonograph recorder.

| Anton Rubinstein: | What a wonderful thing. | Какая прекрасная вещь ....хорошо... |

| Julius Block: | At last. | Наконец-то. |

| Elizaveta Lavrovskaya: | (sings) | |

| Vasily Safonov: | (sings) | |

| Pyotr Tchaikovsky: | This trill could be better. | Эта трель могла бы быть и лучше. |

| Lavrovskaya: | (sings) | |

| Tchaikovsky: | Blok is a good fellow, but Edison is even better. | Блок молодец, но у Эдисона ещё лучше! |

| Lavrovskaya: | (sings) A-o, a-o. | А-о, а-о. |

| Safonov: | Peter Jurgenson in Moscow. | Peter Jurgenson in Moskau. |

| Tchaikovsky: | Who's speaking now? It seems like Safonov's voice. | Кто сейчас говорит? Кажется голос Сафонова. |

| Safonov: | (whistles) |

See also

In Spanish: Antón Rubinstein para niños

In Spanish: Antón Rubinstein para niños

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |