Yosano Akiko facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Yosano Akiko

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 7 December 1878 Sakai, Osaka, Japan |

| Died | 29 May 1942 (aged 63) Tokyo, Japan |

| Occupation | Writer, educator |

| Genre | poetry, essays |

| Notable work | Kimi Shinitamou koto nakare |

| Spouse | Tekkan Yosano |

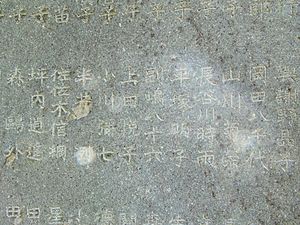

Yosano Akiko (与謝野 晶子; 7 December 1878 – 29 May 1942) was a famous Japanese author and poet. She was also a pioneering feminist, meaning she believed in equal rights for women. Akiko was a pacifist, someone who believes in peace and is against war. She was also a social reformer, working to make society better.

She was active during the late Meiji era, Taishō era, and early Shōwa era in Japan. Her birth name was Shō Hō. Many people consider her one of Japan's most important and sometimes controversial female poets from after the classical period.

Contents

Early Life and Literary Beginnings

Yosano Akiko was born into a wealthy merchant family in Sakai, near Osaka. From the age of 11, she helped a lot with her family's business. They made and sold yōkan, a type of sweet jelly.

Akiko loved reading from a young age. She read many books from her father's large library. When she was in high school, she started reading a poetry magazine called Myōjō (Bright Star). She soon became a regular writer for the magazine.

The editor of Myōjō, Tekkan Yosano, taught her about tanka poetry. They met when he visited Osaka and Sakai to give talks and workshops. Later, they got married.

Akiko was not allowed to leave her home alone when she was young. She later said her childhood felt difficult because of these rules. She married Tekkan when she was 24 years old. They started a new life together in a suburb of Tokyo and were married in 1901. Akiko had 13 children, and 11 of them lived to adulthood.

Midaregami: A Revolutionary Poetry Collection

In 1901, Yosano Akiko released her first book of tanka poems, called Midaregami (Tangled Hair). This book had 400 poems. Many literary critics did not like it at first.

However, many people read it, and it became very popular. It was like a guiding light for people who wanted to think freely. Midaregami was her most famous book. It brought a strong sense of individuality to traditional tanka poetry. This was very different from other works of the late Meiji period.

Most of the poems in Midaregami are love poems. Akiko wrote them to express her feelings for Tekkan Yosano. Through this collection, she created a new image for herself. She also paved the way for other female writers in modern Japan. Her poems often expressed femininity in a way that was unusual for her time, especially for a woman writer.

In traditional Japanese society, women were expected to be gentle and modest. Their main roles were to have and raise children, especially boys. Midaregami talked about ideas and issues important to women. These topics were not usually discussed so openly. The book created a new, revolutionary image of womanhood. It showed women as lively, free, and confident people. This was very different from the usual picture of a quiet, polite young lady in Japan.

Midaregami challenged the traditional values of Japanese society. It also questioned the accepted ways of writing and culture at the time. Even though Akiko Yosano's work was criticized, it greatly inspired women of her era.

A Poet's Busy Life

After Midaregami, Yosano Akiko published more than twenty other tanka poetry books. Some of these include Koigoromo (Robe of Love) and Maihime (Dancer). Her husband, Tekkan, was also a poet. But Akiko's fame grew much larger than his. He continued to help publish her work and encouraged her writing career.

Yosano Akiko was an incredibly productive writer. She could write up to 50 poems in one sitting! During her lifetime, it is believed she wrote between 20,000 and 50,000 poems. She also wrote 11 books of prose, which are stories or essays. Many of these prose works were not as well-known.

Yosano helped start a girls' school called the Bunka Gakuin (Institute of Culture). She worked with Nishimura Isaku and Kawasaki Natsu. Akiko became the school's first dean and main teacher. She helped many new writers get started in the literary world. She always supported education for women. She also translated classic Japanese stories into modern Japanese. These included the Shinyaku Genji Monogatari (Newly Translated Tale of Genji).

Akiko's poem Kimi Shinitamou koto nakare (Thou Shalt Not Die) was very famous. She wrote it for her younger brother. It was published in Myōjō during the Russo-Japanese War. This poem was very controversial. It was even made into a song. People used it as a mild way to protest the war. This happened as news spread about the many Japanese soldiers who died in the bloody Siege of Port Arthur.

In the poem, Akiko asked her brother: "Did our parents make you grasp the sword and teach you to kill? For you what does it matter whether the fortress of Lüshun [Port Arthur] falls or not?" Yosano questioned the idea of Bushido. This was a code that said it was a great honor for a man to die for the Emperor. She pointed out that the Emperor never put himself in danger, but expected others to die for him.

By calling the war with Russia pointless, Yosano became Japan's most controversial poet. The government even tried to ban her poem. Kimi was so unpopular that angry people threw stones at Yosano's house. She also had a big debate with a journalist named Omachi Keigestu. They argued about whether poets should support the war or not.

The first issue of the literary magazine Seito came out in September 1911. It featured her poem "The Day the Mountains Move." This poem asked for women to have equal rights. In an article from 1918, Yosano criticized the "ruling and military class." She said they stopped a truly moral system to protect their families' wealth. She ended her article by calling militarism a "barbarian thinking." She believed women had a duty to get rid of it.

Yosano Akiko had 13 children, and 11 of them lived to adulthood. The later Japanese politician Yosano Kaoru was one of her grandsons.

Akiko's Feminist Ideas

Yosano Akiko often wrote for the all-women literary magazine Seitō (Bluestocking). She also wrote for other publications. Her ideas focused on women sharing equally in raising children. She also believed in women being financially independent and having social responsibility.

On Financial Independence

Yosano Akiko did not agree that mothers should get financial help from the government. She believed that depending on the government was the same as depending on men.

This idea was very different from what many Japanese feminists thought at the time. For example, Raichō Hiratsuka, one of the founders of Seitō, believed the government should support mothers financially. Raichō argued that most women could not realistically live without financial help.

On Motherhood

Even though she gave birth to thirteen children, Yosano said that giving birth was not the most important part of her identity. She also worried that if womanhood was only about motherhood, it would ignore other important parts of a person.

Her main point was that women could be mothers, but they were also much more. They were friends, wives, Japanese citizens, and members of the world.

Yosano believed that motherhood should not be controlled by the government. She thought that marriage and life should be a partnership. She felt that living with one gender having power over the other would lead to "tragic consequences" for everyone.

Later Views and Legacy

During the Taishō period, Yosano started writing about social issues. She wrote books like Hito oyobi Onna to shite (As a Human and as a Woman). In 1931, Yosano, who was known as a pacifist, changed her views. She supported Japan's actions when the Kwantung Army took over Manchuria.

In a poem from 1932 called "Rosy-Cheeked Death," she supported Japan against China. However, she also saw the Chinese soldiers who died as victims. She blamed Chiang Kai-shek for betraying Dr. Sun Yet-sen's ideas of friendship between China and Japan. In this poem, she said the Chinese were "foolish" to fight Japan. She called Japan a "good neighbor" that they could not defeat.

In her poem "Citizens of Japan, A Morning Song" from June 1932, Yosano praised Bushido. She honored a Japanese soldier who died for the Emperor. She described how the soldier's body "scattered" as a "human bomb." Yosano called the soldier's "scattered" body "purer than a flower." She urged Japanese women to "unify in loyalty" for the Emperor's forces.

Yosano's poems from 1937 onwards supported the Second Sino-Japanese War against China. In 1941, she supported the Pacific War against the United States and the United Kingdom. Her later writings often praised Japanese militarism. She also continued to promote her feminist ideas. Her last major work was Shin Man'yōshū (New Man'yōshū). It was a collection of 26,783 poems by 6,675 writers, gathered over 60 years.

In 1942, in one of her last poems, Yosano praised her son. He was a lieutenant in the Imperial Japanese Navy. She urged him to "fight bravely" for the Emperor in "this sacred war." Yosano died of a stroke in 1942 at age 63. Her death happened during the Pacific War and was barely noticed. After the war ended, her works were mostly forgotten.

However, in the 1950s, Kimi became required reading in Japanese high schools. During student protests against the government, Kimi became like an anthem for the students. Her romantic and emotional writing style has become popular again in recent years. She has a growing number of fans. Her grave is at Tama Cemetery in Fuchu, Tokyo.

Works

- Midaregami (みだれ髪) 1901

- Kimi Shinitamou Koto Nakare (君死にたまふことなかれ) 1904

See also

In Spanish: Akiko Yosano para niños

In Spanish: Akiko Yosano para niños

- Japanese literature

- List of Japanese authors

- List of peace activists