Zhou Zuoren facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

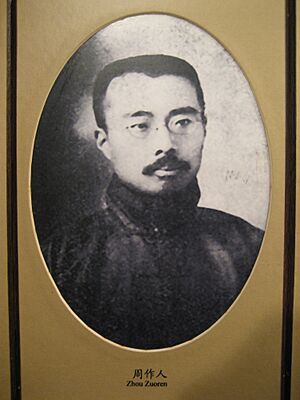

Zhou Zuoren

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Zhou Kuishou (周櫆壽)

16 January 1885 Shaoxing, Zhejiang, Qing Empire

|

| Died | 6 May 1967 (aged 82) Beijing, People's Republic of China

|

| Occupation | Translator, Essayist |

| Partner(s) | Zhou Xinzi (original name: Nobuko Habuto) |

| Children | Zhou Fengyi Zhou Jingzi Zhou Ruozi |

| Parent(s) | Zhou Boyi (father) Lu Rui (mother) |

| Relatives | Zhou Shuren (elder brother) Zhou Jianren (younger brother) |

Zhou Zuoren (Chinese: 周作人; pinyin: Zhōu Zuòrén; Wade–Giles: Chou Tso-jen) was a famous Chinese writer and translator. He was born on January 16, 1885, and passed away on May 6, 1967. He was especially known for his essays and for translating many books into Chinese. He was also the younger brother of another very famous writer, Lu Xun (Zhou Shuren).

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Zhou Zuoren was born in Shaoxing, a city in Zhejiang province, China. As a teenager, he studied at the Jiangnan Naval Academy. In 1906, he moved to Japan, just like his older brother.

While in Japan, he started learning Ancient Greek. His goal was to translate the Gospels into Classical Chinese. He also attended lectures on Chinese language history (called philology) by a scholar named Zhang Binglin. Even though he was supposed to study civil engineering, he focused on literature and languages. He returned to China in 1911 with his Japanese wife and began teaching at different schools.

Role in the May Fourth Movement

Zhou Zuoren was an important figure in the May Fourth Movement and the New Culture Movement. These movements aimed to change Chinese society and culture. He wrote essays in everyday Chinese (called vernacular Chinese) for a magazine called La Jeunesse. He strongly supported making literature more modern.

In 1918, Zhou Zuoren, who was a literature professor at Peking University, wrote an article called "Human Literature." In this article, he said that people should understand and care for each other. He believed that literature should focus on human life. He criticized old traditions where children sacrificed themselves for parents or wives were buried alive with dead husbands. He also thought that traditional performances like Beijing opera were "disgusting" and "pretentious."

Later Years and Legacy

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, some people believed Zhou Zuoren worked with the Japanese government. In 1945, he was arrested and accused of helping the Japanese during their occupation of northern China. He was sentenced to prison in 1947. However, in January 1949, he was released on bail and went back to Beijing.

For the next 17 years, Zhou Zuoren continued his work as a translator. He translated many classic Japanese and Greek books. During the Cultural Revolution, he stopped receiving money for his books, which was his only income. He passed away on May 6, 1967. For a long time, his writings were not widely available in China because of the accusations against him. But in the 1980s, his works became available again, and people could read them. A Chinese scholar named Qian Liqun later wrote a detailed book about Zhou Zuoren's life.

Literature Interests

Zhou Zuoren called his wide range of studies "miscellanies." He even wrote an essay titled "My Miscellaneous Studies." In Tokyo, he became interested in myths, how societies work (anthropology), and what he called ertongxue (the study of children's development).

He became a very skilled translator. He translated many works from classical Greek and Japanese literature. Some of his translations include:

- Greek plays called mimes

- Poems by Sappho

- Tragedies by Euripides

- The Japanese book Kojiki

- Ukiyoburo by Shikitei Sanba

- Makura no Sōshi by Sei Shōnagon

- A collection of Japanese plays called Kyogen

He believed his translation of Lucian's Dialogues, which he finished late in his life, was his greatest literary success. He also translated the story Ali Baba into Chinese from English. In the 1930s, he often wrote for Lin Yutang's humor magazine, The Analects Fortnightly. He wrote a lot about China's traditions of humor, satire, and joking. He even put together a collection of jokes called Jokes from the Bitter Tea Studio. In 1939, he became the chancellor of Beijing University.

Philosophical Views

In his early writings, Zhou Zuoren believed that violence was not the way to modernize China. Instead, he wanted to see social change happen through peaceful discussions and ideas. Before the 1920s, his ideas about literature and philosophy were similar to a style called Romanticism. This meant he focused on individual feelings and experiences.

During the May Fourth era, he continued to believe in what he called "individualist humanism," which means focusing on the value of each person. However, he later changed his mind after seeing how violent things became. He wrote in 1926 that "class struggle was true," like the idea of competition for survival. After the May Fourth Movement, Zhou Zuoren wanted to step back from big national projects and focus more on individual, everyday life.

Between 1940 and 1943, Zhou Zuoren used Confucianism to argue that the Chinese people did not have a "thought problem," as the Japanese claimed. He compared the development of Confucianism in China to a tree. He said that "the tree can grow up again if there was no outside interference." Later, his writing style was also seen to match the ideas of Daoism. In 1944, he explained his "two not-to-be-isms": he didn't want to be a follower, and he didn't want to be a leader. He felt this attitude was like Daoism, even though he called himself a Confucian.

See also

In Spanish: Zhou Zuoren para niños

In Spanish: Zhou Zuoren para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |