1969 Charleston hospital strike facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Charleston hospital strike |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement in South Carolina |

|||

|

|||

| Date | March 19, 1969 – June 27, 1969 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

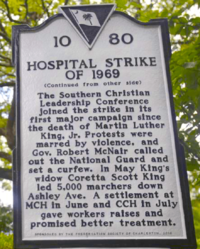

The Charleston hospital strike was a protest that lasted for two months in Charleston, South Carolina. It happened because Black hospital workers were treated unfairly and unequally. The protests started after twelve Black employees were fired for speaking up to the president of Medical College Hospital. This hospital is now called the Medical University of South Carolina. This strike was one of the last big events of the Civil Rights Movement in South Carolina. It was also the first major action by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) since Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated the year before.

Contents

Why the Strike Started: Unfair Treatment at the Hospital

Even after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, Black workers at Charleston's Medical College Hospital still faced unfair treatment. They were treated worse than white employees. Many Black hospital workers tried to meet with Dr. William McCord, the hospital president. They wanted to talk about low pay, unfair treatment, and mean comments they received at work.

For example, a nurse named Mary Grimes-Vanderhorst said she was unfairly moved from being a nurse to a nursing assistant. This happened because of her race, and it meant she earned less money. Other Black nurses and hospital workers said they were paid less than white employees doing the same job. They earned only $1.30 per hour, which was 30 cents below the minimum wage at the time. Black employees also often complained about racist words being used against them. The hospital did nothing to stop employees who made these comments. Some Black workers were not allowed to eat lunch in the break rooms due to segregation. They had to eat outside or in boiler rooms.

In September 1968, some hospital workers contacted Local 1199. This was a national union for health care workers. Local 1199 agreed to start a local group in Charleston called Local 1199B. Mary Moultrie, who also worked at the hospital, became its president.

Local 1199B, with help from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), asked the hospital president to officially recognize their union. But he refused. On March 18, 1969, President McCord agreed to meet with Moultrie and other employees during their lunch break. However, McCord brought a group of people who were against the union. This group was much larger than Moultrie’s group. Moultrie and her colleagues left the meeting because they knew they couldn't reach a fair agreement. Moultrie and eleven other workers briefly protested in the president’s office. The hospital then fired these twelve workers. They were accused of leaving their patients alone. But Louise Brown, one of the fired Black women, said they were on their lunch break. Other staff members were already covering their patients, as usual.

The Strike Begins

Because the twelve Black employees were fired, more than sixty Black hospital workers walked off their jobs on March 19, 1969. They started a strike against the hospital. Both the State of South Carolina and Charleston County, who employed the hospital workers, wanted to stop the union from forming.

Soon after the strike began, the Medical College tried to stop all picketing (protesting outside the hospital). Later, they changed this rule to say that protesters had to stand at least twenty yards apart. A nurse named Naomi White created a group called Hell's Angels. This group went to hospital workers' homes to encourage them to join the strike or protest. However, Moultrie and the SCLC did not know about the Angels.

Governor Robert McNair told the Medical College and Charleston County not to make any deals with the strikers. He urged them to avoid anything that looked like workers coming together to bargain. Governor McNair was worried that this strike would cause more strikes in other jobs across the state.

On April 25, 1969, Governor McNair sent over 1,000 state troopers and National Guardsmen. He also set a curfew from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m. and declared a state of emergency. Some protesters ignored the curfew and continued the strike into the night. By early summer, military vehicles and armed soldiers arrived in the city. Acts of violence against strikers increased. One union member's hotel room was attacked, and mysterious fires started around the city. Mary Moultrie moved out of her home for her family’s safety. She slept on a cot at the union hall, guarded by young people. William Bill Saunders, a Korean War veteran who joined the strike, saw police arresting many people every day. More than 1,000 people were arrested during the conflict.

By the end of April, the movement gained support from Coretta Scott King and SCLC members Andrew Young and Ralph Abernathy. On April 30, Coretta Scott King gave a speech at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. She said, "I feel that the black woman in our nation, the black working woman is perhaps the most discriminated against of all of the working women, the black woman." After her speech, King and Mary Moultrie led a march of 2,000 people. The next week, on Mother's Day, over ten thousand people marched in downtown Charleston. This included five U.S. Congressmen.

These marches caused problems for Charleston's tourism. Protesters filled public streets and markets. Local 1199B created ads encouraging locals to buy only food and medicine. This was meant to further disrupt the city's economy. Most politicians in South Carolina agreed with Governor McNair's actions. However, people in Charleston became more and more frustrated by the ongoing problems. Many businesses in Charleston were negatively affected by the strikes. This was due to strikers blocking stores and the 9 p.m. curfew. Some businesses reported losing as much as 50% of their income. Hotels like the Holiday Inn had to cancel events and conferences. Also, using the National Guard cost $10,000 every day.

Ending the Strike and What Happened Next

A federal investigation found the Medical College Hospital guilty of 37 violations of civil rights. The hospital was threatened with losing $12 million in federal money. President McCord finally gave in. On June 27, 1969, he announced that the hospital and the strikers had reached an agreement.

The Medical College Hospital promised to rehire the strikers the next week. This included the original twelve employees who had been fired. They also agreed to follow a new six-step process for handling complaints and to give small pay raises. Even though the union was never officially recognized by the Hospital or the government, the strike was seen as a success. As a result, Black workers at the Medical College received higher pay and a fairer system for hiring.

A few months after the strike ended, Local 1199 stopped supporting Charleston. They had not been able to get official recognition. In 1970, a political documentary called I Am Somebody, directed by Madeline Anderson, showed the Charleston strikes to people across the country.

On August 15, 1969, two hundred Black sanitation workers in Charleston started a similar strike. They protested and demanded better pay and working conditions. After two months, their strike was also settled with an agreement.

See also

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |