Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Emanuel AME Church |

|

|---|---|

| "Mother Emanuel" African Methodist Episcopal Church |

|

|

|

| 32°47′14″N 79°55′59″W / 32.78722°N 79.93306°W | |

| Location | Charleston, South Carolina |

| Country | United States |

| Denomination | African Methodist Episcopal Church |

| Membership | 1600 (2008) |

| History | |

| Status | Church |

| Founded | 1816 |

| Founder(s) | Rev. Morris Brown Denmark Vesey |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Architect(s) | John Henry Devereux |

| Style | Gothic Revival |

| Groundbreaking | 1891 |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 2500 |

| Number of spires | 1 |

| Administration | |

| Parish | African Methodist Episcopal Church |

| District | Seventh |

Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, often called Mother Emanuel, is a historic church in Charleston, South Carolina. It was founded in 1817. This church is the oldest AME church in the southern United States. The AME denomination itself was the first independent black church group in the nation, started in 1816 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Mother Emanuel has one of the oldest black congregations south of Baltimore.

Contents

A Church with a Rich History

How Mother Emanuel Began

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, a religious movement called the Great Awakening encouraged many people, both enslaved and free, to join Baptist and Methodist churches. Black people were welcomed as members, and some even became preachers. However, white church leaders often kept control. They made black members sit in separate areas or hold services in basements. Laws in Charleston also said that white people had to lead churches.

In Charleston, black members faced more and more unfair treatment. A big problem happened when white leaders of Bethel Methodist decided to build a shed over a burial ground used by black members. This made the black churchgoers very upset.

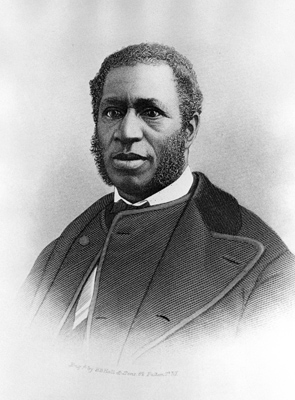

In 1818, a church leader named Morris Brown left Bethel Methodist because of this. Nearly 2,000 black members from three Methodist churches in the city followed him. They wanted to create their own church.

They started a new church, first known as the Hampstead Church. It was part of the "Bethel circuit" of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. This was a new, independent black church group formed in 1816 by Richard Allen and other leaders in Philadelphia.

Challenges and Secret Meetings

At that time, laws in Charleston made it hard for black people to worship freely. Services for black people could only happen during the day. Most people in a church had to be white, and black people were not allowed to learn to read or write. In 1818, Charleston officials arrested 140 black church members. Eight church leaders were fined and whipped. Officials continued to bother Emanuel AME Church in 1820 and 1821.

In June 1822, Denmark Vesey, one of the church's founders, was accused of planning a slave revolt. Vesey and five others were quickly found guilty in an unfair trial. They were executed on July 2.

The city held more trials, and over 30 men were executed. Others were forced to leave the state. The original Emanuel AME church building was burned down by an angry crowd of white people that same year.

Reverend Morris Brown was put in prison for many months, but he was never found guilty of any crime. After he was released, he and other important members moved to Philadelphia. Other members managed to restart the church in secret a few years later.

In 1834, after another slave rebellion led by Nat Turner, the city of Charleston made all-black churches illegal. The AME congregation met in secret until the American Civil War ended in 1865.

Rebuilding and Growth After the Civil War

After the Civil War ended, AME Bishop Daniel Payne appointed Reverend Richard H. Cain as the pastor. The congregation became known as Emanuel ("God with us") AME. In 1872, Cain was elected as a Republican Congressman in the U.S. House of Representatives. This continued a tradition of church leaders also serving in government.

The church was rebuilt as a wooden building between 1865 and 1872. Robert Vesey, the son of church co-founder Denmark Vesey, was the architect. In 1886, an earthquake destroyed that building. President Grover Cleveland donated money to help rebuild the church.

The current brick and stucco building was built in 1891 on Calhoun Street. This area was where black churches were built after the Civil War. The building was designed by a famous Charleston architect, John Henry Devereux. Construction started in 1891 and finished in 1892.

Emanuel AME in the 20th Century

In March 1909, Booker T. Washington, a national leader and president of Tuskegee Institute, spoke at Emanuel AME Church. Many white people attended, including the mayor of Charleston.

By 1951, the church had 2,400 members. It completed a $47,000 renovation project, which was a lot of money back then. The Charleston Chamber of Commerce gave the church an award for its improvements.

In 1962, Reverends Martin Luther King Jr. and Wyatt T. Walker spoke at the church. They encouraged members to register and vote. At that time, most African Americans in the South could not vote due to unfair laws. In 1969, Coretta Scott King, Martin Luther King Jr.'s wife, led a march to the church. About 1,500 people marched to support striking hospital workers. At the church, they faced members of the South Carolina National Guard. The church's pastor and 900 marchers were arrested.

In 1989, Hurricane Hugo damaged the church building. Major repairs were made, and the old tin roof was replaced with copper shingles.

Emanuel AME in the 21st Century

As of 2008, the church had over 1,600 members. It helps local charities like the Charleston Interfaith Crisis Ministry. The church also supports the arts, hosting art shows and concerts.

In 2010, the senior pastor, Rev. Clementa Pinckney, was also a state senator. He followed the example of earlier church leaders, like Rev. Richard H. Cain, who served as both religious and political leaders.

On December 31, 2012, the church held a special service to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. This important document was issued on January 1, 1863. Charleston's yearly Emancipation Day Parade on January 1 ends at Emanuel AME Church.

The 2015 Shooting Event

On June 17, 2015, a tragic event occurred at Mother Emanuel. Nine people were shot and killed inside the church. The victims included South Carolina State Senator Clementa Pinckney, who was the senior pastor, and eight other church members. A tenth person was also shot but survived.

A 21-year-old white male, Dylann Roof, was arrested soon after. He was charged with nine counts of murder. Officials investigated the killings as a possible hate crime, and it was confirmed that they were. The church, on its website, refers to Roof as "the stranger."

In December 2016, Roof was found guilty of many federal hate crime and murder charges. In January 2017, he was sentenced to death for these crimes. Roof also pleaded guilty to the state murder charges in April 2017 to avoid a second death sentence. He was sentenced to life imprisonment for those state crimes.

After the 2015 Shooting

After the shooting, Rev. Dr. Norvel Goff Sr. served as the temporary pastor until early 2016. On January 23, 2016, Rev. Dr. Betty Deas Clark became the pastor. She was the first woman to lead the church in its 200-year history. Currently, The Rev. Eric C. Manning serves as the Senior Pastor.

The Church Building

Built in 1891, Emanuel AME Church has a well-preserved historic interior. Many original parts are still there, like the altar, pews, and light fixtures. In December 2014, the church started raising money to build an elevator to make the building easier to access. A pipe organ was installed in 1902. The church can hold 2,500 people, making it one of Charleston's largest black churches. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2018.

In 2014, it was discovered that termites had caused damage to the building's structure. The church received a grant of $12,330 from the state of South Carolina to study the damage and plan repairs.

Images for kids