African Americans in South Carolina facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,428,796 (2017) | |

| Languages | |

| Southern American English, African-American Vernacular English, Gullah | |

| Religion | |

| Black Protestant | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Gullah |

This article explores the history of African Americans in South Carolina. It highlights their lives, their standing in society, and their important contributions. The first enslaved Africans arrived in the area in 1526. Slavery continued until the Civil War ended in 1865. Before slavery was abolished, less than 2% of the Black population in South Carolina was free.

After the Civil War, during the Reconstruction Era, many African Americans were elected to political jobs. This led to South Carolina having its first government where most leaders were Black. However, by the late 1870s, the Democratic Party took back power. They passed laws to stop African Americans from voting and having rights. Between the 1870s and the 1960s, Black and white people lived separately. They could not go to the same schools or use the same public places. African Americans were treated as second-class citizens. This unfair treatment led to the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s.

Today, African Americans make up 22% of the state's government, called the state's legislature. In 2014, Tim Scott became the first African American U.S. Senator from South Carolina since Reconstruction. In 2015, the Confederate flag was removed from the South Carolina Statehouse. This happened after the Charleston church shooting.

Contents

- Colonial South Carolina: Early Days of Slavery

- The Revolutionary War: A Fight for Liberty, But Not For All

- Early America: The Rise of Cotton and Slavery

- The Civil War: A Fight for the Nation's Future

- Reconstruction Era: A New Beginning for Black Rights

- Post-Reconstruction: Rights Taken Away

- Jim Crow Era and Early 20th Century: Segregation and Inequality

- World War II: Service and Continued Struggle

- Civil Rights Movement: Fighting for Equality

- Modern South Carolina: Progress and Challenges

- Notable African American Scholars and Leaders in South Carolina History

- Notable African Americans from South Carolina

Colonial South Carolina: Early Days of Slavery

Enslaved Africans first arrived in what is now South Carolina in 1526. They came with a Spanish trip from the Caribbean. In 1670, the British Empire took control of the region. The Lords Proprietor set up the Province of Carolina. They created a farming system based on large farms called plantations. These farms increasingly relied on enslaved workers.

By 1708, the number of enslaved Africans in South Carolina was higher than the number of free white people. This Black majority continued in the state until the Great Migration in the early 1900s. There were some small changes in numbers over time.

The Slave Trade: How People Were Bought and Sold

South Carolina's start with slavery was different from northern colonies. It was largely based on a system already in place in the Caribbean. Many of the first white settlers came from Barbados. By 1700, South Carolina's slavery system helped grow the rice and indigo crops. These were important "cash crops" that made a lot of money. Cotton became a big crop later, in the early 1800s.

By the 1700s, most of the slave trade in South Carolina was controlled by the Royal African Company. This company was set up by the British monarchy to trade in West Africa. Slave traders often offered items like iron, copper, brass pans, cowry shells, guns, gunpowder, cloth, and alcohol. In return, they took enslaved Africans. Ships usually carried between 200 and over 600 enslaved people.

Charleston, South Carolina, called Charles Town back then, was a major port for trading goods and enslaved people. More than half of all enslaved people brought to British North America came through Charles Town. By 1770, over 3,000 enslaved Africans were brought to the city each year. The International African American Museum, opening in 2022, is being built in Charleston. It is on the site of Gadsden's Wharf. This was where up to 40% of all enslaved people in America first arrived.

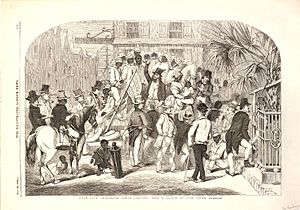

When enslaved people arrived, they were often checked and sold at local markets. Buyers looked at enslaved men to see if they seemed strong. If a man looked weak, old, or sick, he sold for less money. Enslaved people with scars from whippings sold more cheaply. Buyers worried they might be rebellious. Buyers checked enslaved women for beauty and their ability to have children. Both men and women were checked for diseases. They were often stripped of their clothes. Some buyers even forced open their mouths to check their teeth. Enslaved people not bought in Charles Town were forced to travel to other auction houses. These were in places like Georgetown or other colonies.

Slave auctions were also a form of entertainment for many white residents. Even people not planning to buy watched as African men and women were sold. Sometimes, auctioneers offered wine and other drinks to buyers. As slavery grew, the prices of enslaved people went up. By the 1770s, enslaved people sold for as much as $1,500. This was like the price of a new car today. Families were sometimes split apart at these auctions.

Stono Rebellion: Fighting for Freedom

The Stono Rebellion was the largest slave uprising in the British colonies. It led to the deaths of 40-50 Africans and 23 colonists. A slave named Jemmy led the revolt in 1739. He gathered 22 enslaved people near the Stono River in Charleston. They marched, shouting "Liberty," and more enslaved people joined them. The group killed two storekeepers to get weapons and ammunition. Their goal was to reach Spanish Florida. This was a known safe place for those who escaped.

Lieutenant Governor William Bull warned slave owners about the rebellion. Slave owners gathered their local soldiers, called militia, to stop the uprising. The next day, the enslaved people and the militia fought. After the fight, 23 white people and 47 enslaved people were killed. Even though the rebellion failed, it made many governments in British America pass laws. These laws further limited the freedoms of enslaved people and free Black people.

After the Stono Rebellion, South Carolina's government passed more laws. These laws limited the rights of African Americans. They also controlled slavery more strictly. One such law was the Negro Act of 1740. This act stopped enslaved people from gathering, learning to read or write, and moving freely. It also required government approval for each act of manumission (freeing a slave). The law set punishments for slave owners who were too easy on their enslaved people. It required enslaved people to travel with a pass. Any white male could question and hold Black people they thought were escaped slaves.

The Revolutionary War: A Fight for Liberty, But Not For All

During the American Revolutionary War, leaders disagreed on how to reward African Americans who fought for America. Some, like Edward Rutledge and Thomas Lynch, wanted to stop free African Americans from joining the army. Others, like Henry Laurens, thought military service should lead to freedom. Laurens suggested the government pay slave owners $1,000 for each healthy enslaved person under 35 who served. This idea was rejected. Another idea was to give a free slave to any man who joined the army for ten months. This was also rejected.

In the end, enslaved people who served as Patriots were returned to slavery after the war. African Americans in the Continental Army mostly worked as laborers or cooks. Very few fought in battles. Enslaved people usually did not join voluntarily. Most were ordered by their owners to serve in their place. If an enslaved person refused, they could be punished by death. If they were paid, that money went to their owner.

Some African Americans in South Carolina fought for the British. They were called Loyalists. Dunmore's Proclamation promised freedom to any enslaved person who ran away and joined the British army. This promise was not kept because the British lost the war. About 25,000 enslaved people, along with other British Loyalists, left South Carolina after the war. One group of 300 enslaved people from Georgia and South Carolina called themselves "King of England's Soldiers." They hid in the Savannah River swamps until May 1786. Then, the militia found them and burned them out.

Early America: The Rise of Cotton and Slavery

President Thomas Jefferson signed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves in 1807. This law stopped the import of enslaved people. Before it took effect, Charleston traders brought in about 70,000 Africans between 1804 and 1807. For most of the 1800s, enslaved people in South Carolina were born into slavery, not brought from Africa.

By 1860, South Carolina had over 402,000 enslaved people. The free Black population was just over 10,000. At the same time, there were about 291,000 white people in the state. This meant white people made up about 30% of the population. South Carolina had a very large enslaved population compared to other states. It had almost quadrupled in 70 years.

Much of this growth was due to the cotton industry. Before the 1800s, South Carolina's economy relied on tobacco, rice, and indigo. In 1800, the Santee Canal connected the Santee and Cooper rivers. This made it easier to move goods from Columbia, South Carolina to Charleston by water. The canal, along with the invention of the cotton gin, changed cotton production. It became part of the global economy.

The upcountry of South Carolina had good land for growing short-staple cotton. Many planters unknowingly ruined the land by planting cotton year after year. But the cotton industry, driven by enslaved labor, made South Carolina one of the wealthiest places on Earth by the mid-1800s. Slavery spread throughout all of South Carolina. Before, it was mostly along the coast. By 1860, 45.8% of white families in the state owned slaves. This was one of the highest percentages in the country.

Denmark Vesey: A Plan for Freedom

Denmark Vesey was born into slavery in St. Thomas. His owner settled in Charleston after the Revolutionary War. Vesey won $1,500 in a city lottery. He used $600 to buy his freedom. After becoming free, Vesey spent time with many enslaved people. He became determined to help them escape slavery.

In 1821, Vesey and some enslaved people began to plan a revolt. To succeed, Vesey needed to get more people to join his "army." This was not hard because he was a lay preacher. Vesey inspired enslaved people by comparing their fight for freedom to the biblical story of the Exodus. He planned the uprising for July 14, 1822. Vesey held many secret meetings. He gained support from both enslaved and free Black people. They were ready to fight for their freedom.

Vesey planned a surprise attack on the Charleston arsenal. After getting weapons, he intended to take ships from the harbor. Then, they would sail to Haiti. Haiti had recently won its own successful slave revolution. Vesey and his followers also planned to kill white slaveholders in the city. This had happened in Haiti. They also planned to free more enslaved people.

Two enslaved people loyal to their masters, George Wilson and Joe LaRoche, told officials about Vesey's plan. Their stories confirmed an earlier report from another enslaved person named Peter Prioleau. Based on these warnings, the city started looking for the plotters. The Mayor, James Hamilton, organized a group of armed citizens. The city was put on high alert. White groups patrolled the streets daily for several weeks. Many enslaved people were arrested, including Vesey.

Over five weeks, the city court ordered the arrest of 131 Black men. They were charged with planning a conspiracy. In total, 67 men were found guilty and 35 were executed, including Vesey, in July 1822. Thirty-one men were sent away, 27 were cleared, and 38 were questioned and released. Even though Vesey's revolution failed, it led to stricter slave laws and rules against Black people across the country.

Life as an Enslaved Person: Daily Struggles

In South Carolina before the Civil War, slave-owning society had three main groups. The Yeomen class usually owned 1-5 enslaved people. The Middling class usually owned 5-20. The Planter class usually owned over 20. While some enslaved people worked on huge planter-class plantations, others worked on small farms. The planter class made up only 12% of slave owners.

Life as an enslaved person was very different depending on the owner. There were usually three types of slave labor in South Carolina:

- Gang system: This was the most common. Enslaved people worked from sunrise to sunset. This system was often used on cotton plantations and was the most difficult.

- Task system: This system required enslaved people to finish a certain job by the end of the day. It was less common. If tasks were finished early, enslaved people had some time for their own culture.

- Household slaves: These were usually women who worked inside the slave owner's home. They mainly cared for children, prepared food, and cooked.

Slave Codes: Rules and Punishments

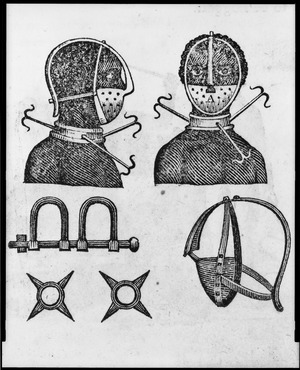

Enslaved people were often forbidden from gathering, practicing their religion, learning to read or write, and owning weapons. However, many of these rules were decided by the slave owner. Here are some examples of slave codes:

- 1712 South Carolina slave code (with changes in 1739, used until the Civil War):

- Enslaved people were not allowed to leave their owner's property unless a white person was with them or they had permission. If an enslaved person left without permission, "every white person" was required to punish them.

- Enslaved people's homes were searched every two weeks for weapons or stolen goods. Punishments for breaking these rules got worse. For the fourth offense, the penalty was death.

- No enslaved person was allowed to work for pay. They could not plant corn, peas, or rice. They could not keep hogs, cattle, or horses. They could not own or use a boat. They could not buy or sell things. They could not wear clothes nicer than "Negro cloth."

- A fine of $100 and six months in prison was given for teaching an enslaved person to read and write. Death was the penalty for sharing writings that could cause rebellion.

Slave Culture: Keeping Traditions Alive

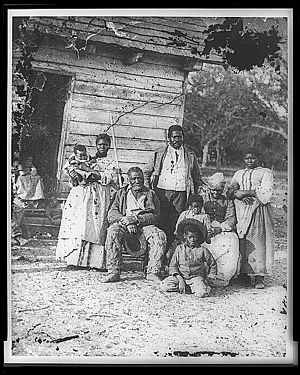

Enslaved people in South Carolina kept their culture alive through food, music, dance, hair, language, and religion. Many sang songs about escaping, like Follow the Drinking Gourde and Wade in the Water.

Gullah People: A Unique Heritage

African Americans in the coastal areas of South Carolina are often called the "Gullah." They are known for keeping more of their African heritage than any other group in the United States. They speak an English-based language called a creole. This language has many African words. It also has strong influences from African languages in its grammar and sentence structure. Gullah storytelling, food, music, folk beliefs, crafts, farming, and fishing traditions all show strong influences from West and Central African cultures.

David Drake: A Talented Potter

David Drake was an enslaved man from Edgefield, South Carolina. He became famous for his pottery. Historians believe Drake made over 40,000 pieces in his lifetime. When Drake was alive, his pottery was worth about fifty cents each. Today, some pieces have sold for as much as $50,000.

Drake often wrote poems or messages on his pottery. Many of these writings were close to being rebellious. This was because enslaved people were generally not allowed to read or write. In one writing, Drake wrote: "I wonder where is all my relations / Friendship to all—and every nation." Drake was likely trying to quietly criticize slavery. For 17 years, Drake did not sign any pots. This was probably because his owner stopped him.

Free Black People: Limited Freedoms

The number of free Black people in South Carolina never went above 2% of the total population. In the North, new economies helped end slavery. But in South Carolina, a lot of money was invested in cotton. This made slavery even stronger. By 1860, the free Black population in South Carolina was still 2%. In contrast, Maryland's free Black population was almost 49%.

It was rare for enslaved people to be freed in South Carolina. This was because manumission (freeing a slave) was generally against the law. For example, in 1850, only two enslaved people gained their freedom. Of the small number of free Black people in South Carolina, 79% were "mulattos." This meant they were people of mixed race. Some slave owners had children with their enslaved people. These children were more likely to be freed than those who were fully of African descent.

Most free Black people lived in the countryside as small farmers. But a small number worked as skilled craftspeople, tenant farmers, or bought their own land. Other free Black people even owned enslaved people for labor. Daria Thomas, a planter in Union District in the 1860s, used many of his 21 enslaved people on his cotton farm. Similarly, William Ellison used 63 enslaved people on his plantation and in his cotton gin business.

However, most freed Black people faced many legal challenges. Since 98% of the state's Black population was enslaved, free Black people constantly had to prove they were free. In the early 1800s, freed Black people were still tried in slave courts. They often faced all-white juries. Free Black people could not speak in court against white people. They were often not allowed in many businesses or public places. Free Black people over 15 years old had to be with a white guardian. These laws became stricter as slave rebellions across the nation made white people fearful. They wanted to stop more uprisings.

The Civil War: A Fight for the Nation's Future

According to historian Walter Edgar, there is no proof that African Americans fought for the South during the American Civil War. Confederate leaders often worried about giving weapons to Black people. Some enslaved people helped the Confederate army. But Black men were not legally allowed to be combat soldiers in the Confederate Army. They worked as cooks, drivers, and manual laborers. They were usually forced to serve. Many enslaved people across the South used the war as a chance to escape to freedom. The Union sometimes called these escapees "contrabands." This meant they were like enemy property that had been taken.

Second Battle of Fort Wagner: Black Soldiers Show Courage

The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment was made up of free African Americans from New England. Some were formerly enslaved or had escaped slavery. This regiment fought at the Second Battle of Fort Wagner in Charleston, South Carolina. Fort Wagner was one of the strongest Confederate forts. On July 18, 1863, the 54th Massachusetts attacked the fort.

The battle lasted almost three hours. Over 1,500 Union soldiers were captured, killed, or wounded. Even though it was a loss on the battlefield, the news of the Battle of Fort Wagner was important. It led to more Black U.S. troops fighting in the Civil War. It also encouraged more people to join the Union Army. This gave the Union a greater number of soldiers than the South.

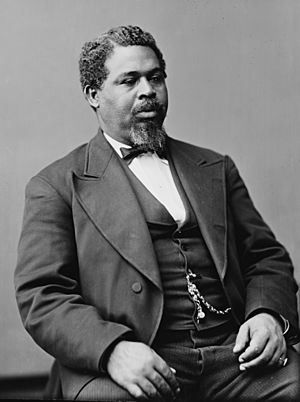

Robert Smalls: A Heroic Escape

Robert Smalls was born into slavery in 1839 in Beaufort County. When he was 12, Smalls' owner sent him to Charleston to work as a laborer. He earned $1 a week, but the rest of his pay went to his owner. Smalls first worked at a hotel, then as a lamplighter. Later, he worked at the docks. He became a longshoreman, a rigger, a sailmaker, and finally a wheelman. Because of this, he knew a lot about Charleston harbor.

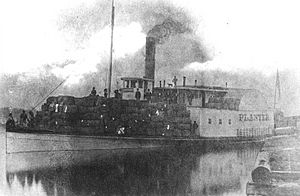

In the fall of 1861, Smalls was told to steer the CSS Planter. This was a lightly armed Confederate military transport ship. The Planter carried messages, troops, and supplies. It also explored waterways and laid mines. On the evening of May 12, the Planter was docked as usual. Its three white officers left to spend the night ashore. They left Smalls and the crew on board, as they often did. (Later, the three Confederate officers faced a military trial. Two were found guilty, but the verdicts were later overturned.)

Around 3 a.m. on May 13, Smalls and seven of the eight enslaved crewmen made their planned escape. They headed for the Union blockade ships. Smalls put on the captain's uniform and a straw hat like the captain's. He sailed the Planter past Southern Wharf. He stopped at another wharf to pick up his wife and children, and the families of other crewmen. Smalls guided the ship past the five Confederate forts in the harbor without any problems. He gave the correct signals at checkpoints. The Planter had been commanded by Captain Charles C. J. Relyea. Smalls copied Relyea's actions and wore his straw hat on deck. This fooled Confederate watchers on shore and in the forts. The Planter sailed past Fort Sumter around 4:30 a.m. The alarm was only raised after the ship was too far away for guns to reach. Smalls headed straight for the Union Navy fleet. He replaced the Confederate flags with a white bed sheet that his wife had brought.

The USS Onward saw the Planter. It was about to fire until a crewman saw the white flag. In the dark, the sheet was hard to see. But the sunrise came, making it visible.

Smalls, who had just turned 23, quickly became known as a hero in the North. Newspapers and magazines wrote about his brave act. The U.S. Congress passed a law giving Smalls and his crewmen prize money for the Planter. The ship was valuable for its guns and its ability to sail in the shallow Charleston bay. Southern newspapers demanded harsh punishment for the Confederate officers. Their night ashore had allowed the enslaved people to steal the boat. Smalls' share of the prize money was $1,500 in 1862.

Smalls became a pilot on the ship Crusader under Captain Alexander Rhind. In June of that year, Smalls was piloting the Crusader on Edisto in Wadmalaw Sound. The Planter returned to service. An army group fought in the Battle of Simmon's Bluff at the Edisto River. He continued to pilot the Crusader and the Planter. As an enslaved person, he had helped place mines (then called "torpedoes") along the coast and river. Now, as a pilot, he helped find and remove them. He also helped with the blockade between Charleston and Beaufort.

After the Civil War, Smalls started the Republican Party of South Carolina. As a Republican, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives five times. He also served in the South Carolina Senate.

Reconstruction Era: A New Beginning for Black Rights

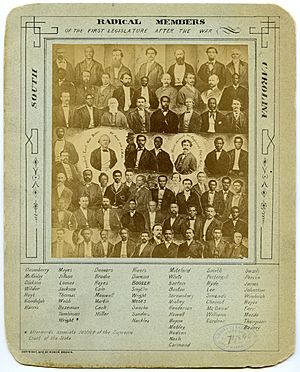

African American Majority in Government

Laws passed during the Reconstruction era greatly expanded the rights of African Americans in South Carolina. These included the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments to the U.S. Constitution. In 1867, U.S. troops registered voters in South Carolina. For the first time, African Americans could vote. Many former Confederates and Southern Democrats chose not to vote. This led to many Republicans voting in the election the next year.

As a result, in the 1868 election, Republicans won by a lot. The new government in South Carolina, the General Assembly, had mostly African American members. As President Andrew Johnson wanted, the new government started creating a new constitution. This constitution would not bring back the old ways of the South.

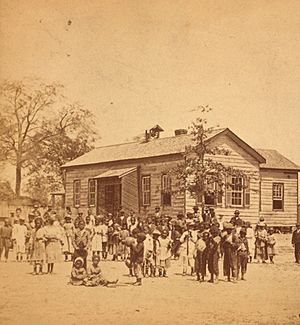

The new constitution made sure that representation was based on population. It did not use the old system based on population and wealth. It removed property requirements for voting. It also guaranteed that all men could vote. The Constitution of 1868 was the first South Carolina constitution to require "a uniform system of free public schools throughout the State." It made marriages between different races legal. It also banned separating people in public places. Anyone who broke anti-segregation laws would lose their business license. They would also pay a $1,000 fine and could be jailed for up to five years.

African Americans were also elected to other important jobs, including federal ones:

- U.S. House of Representatives

- Joseph Rainey

- Robert Smalls (1875-1879; 1882-1883; 1884-1887)

- Alonzo J. Ransier (1873-1875)

- Richard H. Cain (1873-1875; 1877-1879)

- Robert B. Elliott (1871-1874)

- George W. Murray

- Robert C. De Large

- Thomas E. Miller

- Lieutenant Governor

- Alonzo J. Ransier (1870-1872)

- Richard Howell Gleaves (1872-1876)

- Other offices

- Robert B. Elliott, Attorney General (1876-1877)

- Francis Lewis Cardozo, Secretary of State, (1868-1872)

- Richard Theodore Greener, Superintendent of Education

- Jonathan Jasper Wright, Supreme Court (1870-1877)

- Stephen Atkins Swails, mayor of Kingstree

Post-Reconstruction: Rights Taken Away

Black Codes: Limiting Freedoms

Black codes in South Carolina were laws designed to take away civil liberties from African Americans. These codes only applied to "persons of color." This term included anyone with more than one-eighth (12.5%) "Negro blood." Here are some examples of Black codes passed by the South Carolina General Assembly:

XXXV. All persons of color who make contracts for service or labor, shall be known as servants, and those with whom they contract, shall be known as masters.

X. A person of color who is in the employment of a master engaged in husbandry shall not have the right to sell any corn, rice, peas, wheat, or other grain, any flour, cotton, fodder, hay, bacon, fresh meat of any kind, poultry of any kind, animal of any kind, or any other product of a farm, without having written evidence from such master that he has the right to sell such product.

XIV. It shall not be lawful for a person of color to be owner, in whole or in part, of any distiller where spirituous liquors, or in retailing the same, in a shop or elsewhere

LXXII. No person of color shall pursue or practice the art, trade or business of an artisan, mechanic or shop-keeper, or any other trade, employment or...on his own account and for his own benefit, or in partnership with a white person, or as agent or servant of any persons, until he shall have obtained a license therefore from the Judge of the District Court; which license shall be good for one year only.

The Black codes were an effort by Democrats and white supremacists. They wanted to keep a system of racial inequality. This system had existed before the Civil War. Black codes, along with poll taxes, literacy tests, and threats, meant that the Democratic party in South Carolina faced almost no opposition. This lasted until the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s.

Voter Suppression: Making it Hard to Vote

Between the mid-1870s and the early 1970s, African Americans in South Carolina mostly could not vote. The Fifteenth Amendment protected Black men's right to vote. But poll taxes, literacy tests, and threats from groups like the Ku Klux Klan made it very hard. As a result, very few African Americans voted in elections. By 1940, African American voters made up only 0.8% of those old enough to vote in the state.

Literacy Tests and Poll Taxes: Barriers to Voting

South Carolina required voters to fill out a voter application. One rule was that voters had to be able to "(a) both read and write a section of the Constitution of South Carolina; or (b)...have paid all taxes due last year on property in this State assessed at $300.00 or more." Many former enslaved people could not read. Many also could not afford the $300 property tax. Because of this, they were not allowed to vote.

The test was very unfair. The person giving the test, almost always a white male, could stop anyone from voting based on his own opinion. For example, if a man read the entire South Carolina constitution but mispronounced one word, the examiner could still refuse him the right to vote. The state of South Carolina said that poll taxes were not about voting. They claimed it was a way to pay for public schools. However, historians today disagree with this. In 1923, South Carolina's poll tax was $1.00. This is about $15 in today's money. After the Civil War, many African Americans worked as sharecroppers. They earned very little money. In the 1920s, the average weekly pay for a sharecropper was $5 to $6. The $1.00 poll tax would have been about one day's pay, or 20% of one week's pay.

Intimidation: Threats and Violence

Toward the end of Reconstruction, African Americans were discouraged from voting. This happened through threats and violence. The Ku Klux Klan, or KKK, was a major terrorist group in the state. It appeared in the 1870s. In 1871, evidence showed that African Americans were being killed or terrorized by the Klan. In York County alone, eleven African Americans were murdered and 600 were whipped. Governor Robert Scott refused to declare martial law or fight the Klan's violence.

Later that year, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Ku Klux Klan Act. This law made it a federal crime to stop any American citizen from using their rights. In nine South Carolina counties, Grant declared martial law. He arrested about 600 Klansmen. Fifty-three pleaded guilty, and five were found guilty in court. For a while, the number of lynchings and acts of terror went down a lot. But they increased again after the Compromise of 1877. In this agreement, President Hayes removed federal troops from the South.

Klan activity in South Carolina was much stronger in the upstate. This was where the African American population was not as large. Between 1882 and 1968, there were 4,743 reported lynchings in South Carolina. However, many historians believe this number is too low. They say that as many as 60% of lynchings were not reported or recorded. Most victims killed or hurt by the Klan were Republican African Americans. Some Republican white people also suffered, but in smaller numbers.

A group with similar goals to the Ku Klux Klan was the Red Shirts. Their 1876 "Battle Plan" said: "Every Democrat must feel honor bound to control the vote of at least one Negro, by intimidation...In speeches to Negroes you must remember that they can only be influenced by their fears, superstitions and cupidity. Treat them so as to show them you are the superior race and that their natural position is that of subordination to the white man." The Red Shirts were less secret than the KKK. They worked more openly. But both groups had the same goal: to bring Democrats back to power.

Jim Crow Era and Early 20th Century: Segregation and Inequality

Legal Limitations: Laws That Separated People

After the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) court decision, separating people by race was legal across the United States. However, this separation was already deeply rooted in South Carolina's culture. In a 1900 speech, South Carolina U.S. Senator Benjamin Tillman said: "We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern the white man, and we never will. We have never believed him to be equal to the white man. I would to God the last one of them was in Africa and that none of them had ever been brought to our shores."

Starting in the late 1870s, Democrats canceled most of the laws passed by Republicans during Reconstruction. This took away civil liberties and rights from African Americans in South Carolina. For example, an 1879 law made marriages between different races illegal. It stated: "Marriage between a white person and an Indian, Negro, mulatto, mestizo, or half-breed shall be null and void." This law was not overturned until the Loving v. Virginia (1967) Supreme Court case.

In 1895, the General Assembly created a new constitution. It required: "No children of either race 'shall ever be permitted to attend a school provided for children of the other race.'" An 1898 law required railroad companies to have separate cars for white and "colored" passengers. A similar law in 1905 required streetcars to be segregated. State and city laws stopped white and Black people from eating in the same part of a restaurant. They also couldn't use the same public facilities, like drinking fountains or bathrooms. Separate seating was required. A 1952 state law forced cotton textile factories to stop different races from working together in the same room. They also couldn't use the same exits or bathrooms. Another 1952 law made it a crime for any "colored" person to adopt or take care of a white child.

African Americans also struggled to get skilled jobs. Many worked as sharecroppers, earning very little money. Factories and business owners often preferred white employees over Black employees. If Black employees were hired, they were usually paid less than white people. In 1896, Lucy Hughes Brown became the first Black female doctor in the state. She helped start the Hospital and Training School for Nurses in 1897 with Alonzo Clifton McClennan, a Black doctor.

Cultural rules in Jim Crow South Carolina also kept African Americans in a lower position. For example, a South Carolina custom required African Americans to address white people in certain ways: "If you are white, never say 'Mr.', 'Mrs.', 'sir', or 'ma'am' to nonwhites and always call them by their first names. If you are nonwhite, always say 'Mr.', 'Mrs.', 'sir', or 'ma'am' to whites and never call them by their first name." These unwritten rules stopped white and Black people from shaking hands. They also required Black people to take off their hats when speaking to white people. Not following these rules could lead to Black people being arrested, whipped, or lynched. Federal changes meant to help African Americans mostly failed. The Freedmen's Bureau was largely ineffective. The 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments were denied to African Americans in practice.

Charleston Race Riots of 1919: A Violent Outbreak

In Charleston, five white men at the Charleston Naval Shipyard felt they had been cheated by a Black man. They searched for him. When they couldn't find him, they attacked African Americans randomly. One of the men they attacked, Issac Doctor, fired his weapon to defend himself. News of the shooting spread quickly. Within an hour, over 1,000 white sailors and some white citizens gathered in the street. The white sailors raided shooting galleries and stole guns. The crowd marched around the city, attacking African Americans and their businesses and homes. Some businesses were looted.

Police brought the riot under control by 2:30 a.m., three and a half hours after it started. As a result, 6 African Americans died. Seventeen suffered serious injuries, and 35 were taken to hospitals. Seven white sailors and one police officer were seriously injured. Eight sailors were admitted to hospitals. Police arrested 49 men accused of starting a riot, but the charges were dropped due to lack of evidence. Eight people received $50 fines for having weapons illegally.

The Great Migration: Leaving the South

The Great Migration was when 6 million African Americans moved from the rural Southern United States. They went to cities in the Northeast, Midwest, and West. This happened between 1916 and 1970. In 1900, South Carolina's African American population was about 58%, meaning they were the majority. By 1970, the population dropped to 30%. African Americans left the state to escape Jim Crow laws, racial violence, and to find better-paying jobs.

World War II: Service and Continued Struggle

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, African Americans in South Carolina still lived in separate neighborhoods. They went to separate schools and used separate public places. Many young African American men joined the military, either by choice or by the draft. They went to Europe and the South Pacific after the Bombing of Pearl Harbor. They fought against the Axis. The military remained segregated until President Harry Truman signed an executive order after World War II to integrate the armed forces.

All servicemen faced challenges during their time in the military. But African Americans faced even greater difficulties. Bura Walker was a Black soldier who was promoted to warrant officer at Fort Jackson (South Carolina)Fort Jackson. Very few African Americans reached this rank. Because of the state's segregation laws, Walker could not move into the officer quarters. This was because his fellow officers were all white. Many Black veterans remembered being treated worse by officers than white soldiers. They also felt their fellow soldiers did not respect them.

African Americans who stayed in South Carolina still struggled to participate in politics. They were often denied skilled jobs. The Charleston Naval Yard, which mostly hired white men before the war, saw a large increase in female and African American workers during World War II. More than 6,000 Black people were hired by the Naval Yard. However, when the war ended, white veterans were usually preferred over Black employees.

In the summer of 1942, rumors spread that Black citizens were collecting war materials in Charleston. This convinced the mayor to cancel the annual Black Labor Day parade. Another Charleston resident remembered seeing two African Americans try to sit at the front of a city bus. This was strictly forbidden by the Jim Crow laws at the time. When the bus driver told them to move back, they seemed to hesitate. The driver then pulled out a pistol and ordered the two African Americans to the back. They quickly obeyed, and nothing else happened.

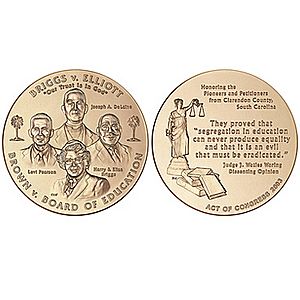

Civil Rights Movement: Fighting for Equality

Like much of the nation in the 1950s and 1960s, African Americans in South Carolina led peaceful protests. They protested against unfair segregation laws. However, much of the national attention during the civil rights movement focused on Alabama and Mississippi. Most of the civil rights movement in South Carolina happened without many riots or violence, except in a few cases.

In Greenville, the Greenville Eight were African American college students. They protested the segregated library system by entering the white-only branch. In Columbia, Black students from Allen University and Benedict College led protests throughout the city. In Orangeburg, South Carolina, students from South Carolina State University and Claflin University led protests and marches to challenge segregation.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, many businesses, schools, and governments resisted integration. In 1956, U.S. Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina wrote the Southern Manifesto. This document criticized the 1954 Brown v. Board decision. It called it "unwarranted" and referred to anti-segregationists as "agitators and troublemakers invading our States." Many school districts ignored the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. Some districts were still segregated into the 1970s.

Modern South Carolina: Progress and Challenges

Politics: African Americans in Leadership

In 1993, Jim Clyburn was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina's 6th congressional district. Clyburn served as the House Majority Whip from 2007 to 2011, and from 2019 to the present. In 2012, Governor Nikki Haley appointed U.S. Representative Tim Scott to fill a vacant spot. Scott became the first African American man to serve in the U.S. Senate from South Carolina. Scott won the 2014 special election and was reelected in 2016.

In July 2010, Stephen K. Benjamin became the first African American mayor of Columbia. In 2006, Terence Roberts became the first African American mayor of Anderson. In 2015, Barbara Blain-Bellamy became the first African American female mayor in the state, in Conway. In December 2019, Barry Walker became the first African American mayor of Irmo.

As of 2020, 44 of the 172 members of the South Carolina General Assembly were African American. This accounts for about 26%.

In the 2016 Presidential Election, African Americans in South Carolina mostly voted for the Democratic Party. According to a CNN exit poll, 94% of voting African Americans voted for Hillary Clinton. Four percent voted for Donald Trump, who won the state's nine electoral votes.

Demographics: Population Changes

According to 2017 estimates, African Americans make up 27.3% of South Carolina's population. This number has been slowly going down since the early 1900s.

According to the 2010 census, out of South Carolina's 46 counties, 12 have a majority-Black population. The counties with Black populations above 55% are:

- Allendale, 73.6%

- Williamsburg County, 65.8%

- Bamberg County, 65.5%

- Lee County, 63.3%

- Orangeburg County, 62.2%

- Fairfield County, 59.1%

- Marion, 55.9%

| African American |

| White American |

| Other |

Historical South Carolina Racial Breakdown of Population

Recent Events: Protests and Marches

George Floyd Protests: Standing Up for Justice

After the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota on May 25, 2020, protests happened across the United States. In South Carolina, most protests were peaceful. Many large cities set curfews after a day of violence. Several businesses and restaurants in downtown Columbia were damaged. Protesters burned three police cars. They also tried to burn down several buildings, but were not successful. In Charleston, protesters stopped traffic on Interstate-26.

Million Man March (2020): A Call for Change

On June 14, 2020, thousands of people marched from Martin Luther King Park in Five Points to the Statehouse in Columbia. The march honored the Million Man March held in Washington, D.C. in 1995. According to Leo Jones, the event's organizer, the march aimed to protest racial injustice. It was also a continuation of the George Floyd protests from previous weeks. Marchers were asked to wear their "Sunday best." They were also encouraged to register to vote after the march if they hadn't already. Tents were set up on the Statehouse grounds for voter registration. Columbia Mayor Stephen K. Benjamin, Richland County Sheriff Leon Lott, and Columbia Police Chief Skip Holbrook joined the march. Groups like 100 Black Men and the NAACP also supported the march.

Notable African American Scholars and Leaders in South Carolina History

- Septima Poinsette Clark - an educator and civil rights activist.

- Esau Jenkins - a human rights leader, businessman, preacher, and community organizer.

- Valinda W. Littlefield, Ph.D. - a USC Professor who studies African American History and is a community leader.

- Walter Edgar - an American historian and author who specializes in Southern history and culture.

Notable African Americans from South Carolina

Science

Politics

- Charlotta Bass - newspaper publisher, Civil Rights leader, first African-American woman to run for national office – Vice President of the United States.

- Harvey B. Gantt

- Jesse Jackson

Healthcare

- Anna DeCosta Banks - a pioneer in nursing.

- Lucy Hughes Brown

- Matilda Evans

- Alonzo Clifton McClennan

Education

- Augusta Baker - the University of South Carolina's Storyteller-in-Residence.

- Mary McLeod Bethune - founder of Bethune-Cookman University, Special Advisor on Minority Affairs to President Roosevelt, and founder of the National Council for Negro Women.

- Septima Poinsette Clark

- Mary Gordon Ellis

- Ruby Middleton Forsythe

- Lucille Simmons Whipper

Law

Military

- Webster Anderson - received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his service in the Vietnam War.

Entertainment and Art

- Charlamagne Tha God - Radio personality, actor.

- Kimberly Clarice Aiken - Miss America 1994.

- Clayton "Peg Leg" Bates - a tap dancer.

- Paul Benjamin - actor.

- Kitty Black Perkins - principal designer for Mattel's Barbie fashions.

- Chadwick Boseman

- James Brown

- Chubby Checker

- Viola Davis

- Althea Gibson

- Dizzy Gillespie

- Mary Jackson (artist)

- Eartha Kitt

- Darius Rucker

- Cecil J. Williams

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |