Prize money facts for kids

Prize money was a special reward paid to sailors and privateers (private ships allowed to attack enemy vessels) for capturing enemy ships or valuable goods during wartime. It was like a bonus for their bravery and success at sea!

Imagine a time when countries were often at war. If a warship or a privateer ship captured an enemy vessel or its cargo, the crew could get a share of the money from selling what they captured. This money was usually decided by a special court called a prize court.

Prize money wasn't just for wartime captures. It was also given for catching pirate ships, slave ships (after the slave trade was made illegal), or ships that broke trade rules. There were also similar rewards, like "gun money" or "head money," paid for sinking or destroying armed enemy ships.

Sometimes, armies captured valuable things on land, which was called "booty of war." This was different from naval prize money because it was usually for specific captures, like taking over a city.

Even though prize law still exists, paying prize money to privateers stopped in the mid-1800s. Most countries also stopped paying prize money to their navy personnel by the mid-1900s.

Contents

How Prize Money Started

The idea of prize money came from old maritime laws from the Middle Ages. These laws said that rulers of countries had rights over property found or captured at sea. Later, in the 1500s and 1600s, legal experts like Hugo Grotius developed international laws. They believed that only a country's government could declare war, and anything captured from an enemy belonged to that country's ruler.

However, it became a custom for the ruler to share some of this wealth with the sailors who made the captures. In the 1600s, rulers often kept a small part (like one-tenth to one-fifth) of what privateers captured. They kept more (up to half) of what their own navy captured. It was also a rule that a captured ship had to be brought to port or held for 24 hours. No money could be shared without a court's approval.

Most European countries had similar prize laws that offered rewards for captures. However, we know more details about the rules in England (which later became Great Britain and the United Kingdom), France, the Dutch Republic, and the United States. Smaller navies, like those of Denmark and Sweden, didn't get much prize money because they had fewer chances to capture enemy ships.

Booty of War: Prizes on Land

"Booty of war" (also called "spoils of war") was enemy property captured on land, like weapons or equipment. This was different from "prize," which was property captured at sea. Legally, booty belonged to the winning country. But often, some or all of its value was given to the soldiers who captured it.

In Britain, the Crown (the ruler) could grant booty for specific captures, like the Siege of Seringapatam in 1799 or the Siege of Delhi in 1857. This was done by special announcements, not general laws for all captures. The United States and France also allowed their soldiers to profit from booty, but they stopped this practice around 1900. Today, international rules like the Third Geneva Convention only allow military equipment of prisoners of war to be seized. They do not allow awarding booty.

Prize Money in England (Before 1707)

From medieval times, the English Crown had rights over certain property found or captured at sea or on the shore. This included shipwrecks, abandoned ships, and enemy ships or goods captured in wartime. These rights were known as "Droits of the Crown." Later, when the office of the High Admiral was created in the 1400s, these rights were given to him and became known as "Droits of Admiralty."

At first, there wasn't much difference in how rewards were given to Royal Navy sailors and privateers. Privateers were civilians who had "letters of marque" from the Crown, allowing them to attack enemy ships. In the Middle Ages, rulers didn't have a good system to decide on prizes or collect their share. The first Admiralty Court in England for prize issues was set up in 1483.

From the time of Elizabeth I, the Crown insisted that courts had to decide if a prize was valid and how much it was worth. The Crown always kept a part of the value. If an English ship didn't bring a captured prize to court, the ship itself could be taken away! The Crown decided how much to give to the captors and how to share it among the owners, officers, and crew. Usually, the Crown kept one-tenth of the value of prizes captured by privateers.

Sailors on navy ships had an old custom called "free pillage." This meant they could take the enemy crew's personal belongings and any goods not stored in the ship's hold. The government tried to stop this in 1652, but it was too hard to enforce. So, the right to pillage was made legal again later.

In 1643, a new rule allowed privateers to keep any captured ships and goods after a court decision, as long as they paid one-tenth of the value and customs duties. In 1649, a rule for navy ships said that sailors and junior officers could get half the value of a captured enemy warship. They also got "gun money" (10 to 20 pounds) for every gun on an enemy warship that was sunk. They got one-third of the value of a captured enemy merchant ship.

If a captured enemy warship could be repaired and used by the English fleet, the Crown might buy it. But until 1708, the price was set by the Admiralty, and people suspected they valued ships too cheaply. The 1643 rule also said that some prize money not given to the crew would go to the sick and wounded. Also, English ships recaptured from the enemy had to be returned to their owners, who paid one-eighth of their value to the recapturing ship. These rules were also applied to capturing pirate ships.

Anglo-Dutch Wars: Big Prizes and Problems

Before the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–1667) began, England took steps that caused problems with the Netherlands. First, the Navigation Acts in 1663 allowed English ships to capture any vessels breaking these trade rules. Captors could get one-third of the value, the colonial governor one-third, and the Crown one-third. Second, in 1664, prize money for English sailors was increased to 10 shillings for each ton of a captured ship, plus at least 10 pounds per gun for any warship sunk.

Even though King Charles II was usually generous with prize money, a scandal happened in 1665. The Earl of Sandwich, a naval commander, captured many valuable Dutch merchant ships. Worried that the King might not be generous, he and another officer, Sir William Penn, decided to take valuable goods for themselves from the captured ships. This was against the rules, which said all goods had to be declared in court first.

Some officers refused to take the goods, and the junior captains complained. Many English sailors also joined in the looting, and a lot of valuable spices were stolen or ruined. The Earl of Sandwich lost his command. This event showed how important it was to follow the rules for prize money.

English privateers were very active during the Anglo-Dutch Wars. They attacked Dutch trade and fishing, capturing many Dutch merchant ships.

War of the Spanish Succession: New Rules

The situation for ship captains improved with a Prize Act in 1692. This law made a difference between captures by privateers and by royal ships. Privateers could keep any captured ships and four-fifths of the goods, giving one-fifth to the Crown. They could sell their prizes and share the money as they wished.

However, for royal ships, one-third of the prize value went to the officers and men, and one-third to the King (who could reward flag officers). The final one-third went to the sick and wounded, and for the first time, also to families of killed crew members and to fund Greenwich Hospital.

The 1692 act also ended the old right of pillage. It set gun money at 10 pounds per gun and arranged for salvage payments to owners of English ships recaptured from the enemy. Before 1692, how the officers and men shared their one-third of prize money was based on custom. But then it was fixed: one-third to the captain, one-third to other officers, and one-third to the crew.

During this war (around 1701), the Admiralty set up a board of prize commissioners. These agents were in charge of captured ships until a court decided if they were legal prizes. While privateers could sell their prizes after court approval, the commissioners sold ships and goods captured by royal ships. They also valued ships bought for the Royal Navy and calculated prize money payments.

Many naval battles happened far away, like in the Mediterranean. Some captains sold captured ships without bringing them to a prize agent, often cheating their own crews. A Royal Proclamation in 1702 warned captains that they could be court-martialed if they didn't use prize agents. If a court found a capture was illegal, the ship and cargo were returned, and the captor had to pay for any losses.

Prize Money in Great Britain (1707 to 1801)

After England and Scotland united in 1707 to form Great Britain, the English prize money rules applied to the whole country. The War of the Spanish Succession continued until 1714.

A law from 1708, called the Cruisers and Convoys Act, aimed to protect British trade. It encouraged navy ships to protect convoys and attack enemy warships. It also encouraged both navy ships and privateers to attack enemy merchant ships. The main changes were:

- The Crown no longer took a share from merchant ships and their cargoes captured by navy vessels or from goods captured by privateers.

- "Head money" was introduced: five pounds for each crew member of a captured or sunk enemy warship. This replaced gun money.

Like other prize laws, this act ended in 1714. However, its rules were largely repeated in later prize acts during other wars. Sometimes, if an enemy merchant ship was captured far from a court, the captor might offer to ransom it for a percentage of its value. But in 1815, ransoming was mostly forbidden.

The 1708 act still required captured ships to be held by prize agents before a court decision. Customs duties also had to be paid on captured goods. But once these duties were paid, Royal Navy captors could sell the goods themselves for the best price. This act also allowed navy captains, officers, and crews to hire their own experts and agents to help with prize money. These changes helped many people make fortunes from prize money in the 1700s and early 1800s.

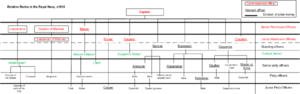

In the Georgian navy, prize money shares depended on rank. Senior officers received much larger individual shares than junior officers and ordinary sailors. In the 1700s, an admiral might get one-eighth of the value of all prizes taken by his fleet. If there was more than one admiral, they shared that eighth. A captain usually received one-quarter of his prize's value, or three-eighths if not under an admiral's command. Other officers shared another quarter, and the crew shared the rest. Any ships that were in sight of a battle also shared in the prize money. Unclaimed prize money went to Greenwich Hospital.

During the Seven Years' War, privateer crews from British colonies often received wages plus a share of prize money. But crews from British ports usually got no wages. The cost of their food was taken from their prize money. Privateer owners generally took half the prize value and an extra 10% for fees. The captain usually got 8%, leaving 32% for other officers and crew. This was often divided into shares, with officers getting much more than ordinary sailors.

Big Prize Money Awards (1707 to 1801)

One of the largest prize money awards for capturing a single ship was for the Spanish frigate Hermione in 1762. It was captured by the British frigate Active and sloop Favourite. The two captains, Herbert Sawyer and Philemon Pownoll, each received about £65,000! Each sailor and Marine got £482 to £485. The total prize money for this capture was £519,705 after expenses.

However, the capture of the Hermione didn't lead to the biggest award for an individual. After the Siege of Havana in 1762, many Spanish ships and military equipment were captured. The naval commander, Vice-Admiral Sir George Pocock, and the military commander, George Keppel, 3rd Earl of Albemarle, each received £122,697! The naval second-in-command, Commodore Keppel, received £24,539. Each of the 42 naval captains present got £1,600. But ordinary soldiers and sailors received much less, around £4 each.

In October 1799, the capture of the Spanish frigates Thetis and Santa Brigada brought in £652,000. This was split among the crews of four British frigates. Each captain was awarded £40,730, and the sailors each received £182 4s 9¾d, which was like 10 years' pay!

Prize Money in the United Kingdom (From 1801)

After Great Britain and Ireland united in 1801 to form the United Kingdom, the British prize money rules continued. The Napoleonic Wars began in 1803.

New prize acts repeated the rules from 1708. In 1812, the rules for sharing prize money were changed again. The admiral and captain together received one-quarter of the prize money, with the admiral getting one-third of that. This was less than before. Lieutenants and sailing masters received one-eighth, as did warrant officers. The crew below warrant officer rank now shared one-half of the prize money. However, this group was divided into many grades, with higher grades getting more.

The many prize money grades continued until 1918. The Naval Agency and Distribution Act of 1864 was a permanent law. It said prize money would be shared according to a Royal Proclamation or Order in Council. This act didn't include privateers because the United Kingdom had signed the Declaration of Paris, which made privateering illegal for signatory nations.

The Prize Courts Acts of 1894 said that rules for prize courts and prize money would be set by an Order in Council at the start of any war. The Naval Prize Act 1918 changed the system. Prize money was no longer paid to individual ship crews. Instead, it went into a common fund, and all naval personnel received a payment from it. This money was paid after the war ended. This system was used in the two World Wars. In 1945, it was changed to include Royal Air Force (RAF) personnel who helped capture enemy ships. The Prize Act 1948 officially ended the Crown's right to grant prize money in wartime.

Fighting Slavery: A New Kind of Prize Money

After Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807, a new source of prize money appeared. Royal Navy ships of the West Africa Squadron captured slave ships. Under a rule from 1808, the government paid £60 for each male slave freed, £30 for each woman, and £10 for each child under 14. This was paid instead of prize money for the slave ship itself, which became the British government's property. This money was shared like other prize money.

Between 1807 and 1815, the government paid Royal Navy personnel £191,100 for freeing slaves in West Africa. Captured slave ships were usually sold and re-registered as British ships. However, in 1825, the payment for all slaves was reduced to a flat rate of £10, and then to £5 in 1830. Later, in 1839, prize money was increased again to £5 for each slave landed alive, half that for slaves who died, and £1 10s for each ton of the captured ship's size.

During much of the Napoleonic wars until 1812, prize money was divided into eighths.

- Two-eighths went to the captain or commander. This often helped them become rich and powerful.

- One-eighth went to the admiral or commander-in-chief who gave the ship its orders. (If orders came directly from London, this eighth also went to the captain).

- One-eighth was shared among the lieutenants, sailing master, and captain of marines.

- One-eighth was shared among the wardroom warrant officers (like the surgeon and purser), standing warrant officers (like the carpenter and boatswain), lieutenant of marines, and master's mates.

- One-eighth was shared among junior warrant and petty officers, their mates, marine sergeants, the captain's clerk, surgeon's mates, and midshipmen.

- The final two-eighths were shared among the rest of the crew. Skilled seamen got more shares than ordinary seamen, landsmen, and boys. For example, an able seaman got two shares, an ordinary seaman one and a half, landsmen one share, and boys half a share.

In 1807, Captain Peter Rainier received £52,000 when his frigate Caroline captured the Spanish ship San Rafael.

Problems with Prize Money Payments

For much of the 1700s and early 1800s, the main complaints about prize money were delays in payment and practices that cheated ordinary sailors. While captains selling captured ships abroad became less common, payments were often made with a promissory note (a "ticket") that would be paid later. Officers could usually wait, but most sailors sold their tickets at a big discount to get cash immediately. Other sailors authorized someone else to collect their money, but it wasn't always passed on. Also, if a ship's value was decided in an overseas court, it could be re-evaluated in Britain, leading to delays and lower payments.

Delays also happened because courts took a long time to decide if captured ships were legal prizes and what they were worth. For example, in the War of 1812, courts in Halifax, Nova Scotia, had to deal with many small American ships, causing long legal delays. Even after a decision, it could take three years or more from capture to payment.

Under "joint capture" rules, any Royal Navy ship present during a capture could share in the prize money. But this led to arguments, for example, if ships were chasing a vessel but out of sight when another ship captured it. To avoid disputes, crews on the same mission sometimes made agreements to share prize money. For privateers, a ship had to actually help with the capture to claim a share, unless there was a prior agreement.

Prize Money in Scotland and Ireland

The Kingdom of Scotland had its own Lord High Admiral from medieval times until 1707. His power over Scottish ships, waters, and coasts was similar to England's Admiral. Scotland's fleet was small, but it commissioned many privateers during the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–67) and Third Anglo-Dutch Wars (1672–74).

Scottish privateers were quite successful, especially in the Second Anglo-Dutch War. They attacked Dutch and Danish merchant ships, many of which were poorly armed. These enemy ships often had to sail around northern Scotland to avoid the English Channel, making them easy targets for Scottish privateers. Privateer owners usually got most of the prize money, as their sailors often worked for wages instead of a share of the prize.

Ireland's Admiralty Court

Ireland also had an Admiralty Court from the late 1500s. It was mainly run by English officials and had similar powers to the English court. It mostly dealt with the many pirates operating off the Irish coast. The Irish Admiralty didn't have its own ships and couldn't issue Letters of Marque to privateers. However, it could seize and condemn pirate and enemy ships in Irish ports.

During the War of the Austrian Succession in 1744, the Irish Admiralty Court gained more power. It became an independent prize court, similar to the Vice-Admiralty courts in British colonies.

Prize Money in France

In France, the Admiral of France handled prize cases until that office was abolished in 1627. A group of legal experts, the prize council (Conseil des Prises), was set up in 1659 to decide on all prizes and prize money. Many French privateers tried to avoid its review. The Prize Council only operated during wartime until 1861, when it became permanent until 1965.

French Navy officers and sailors were supposed to get prize money, but awards were rare. French naval strategy often switched between building a strong battle fleet and using privateers to attack enemy trade. When financial problems prevented a large battle fleet, France often relied on privateers. Even when a battle fleet was active, French naval rules often focused on defensive tactics, which meant fewer captures and less prize money.

When France focused on attacking trade, many smaller warships were leased by the Crown to private contractors. These contractors paid for the ships and agreed to give the Crown one-fifth of all captures. These ships were treated as privateers. Other privateers were fully funded by private individuals. These privateers operated outside government control. This privateering often meant the French Navy struggled to find experienced seamen.

Under a rule from 1681, privateers had to register and pay a large deposit. Any prize had to be checked by the prize council, which took a tenth of the money for the Admiralty. Officers and men of the French Royal Navy were supposed to share four-fifths of the value of a captured merchant ship. One-tenth went to the Admiralty, and another tenth went to sick and injured seamen. The prize council was known for long delays, during which captured ships and their goods often spoiled.

Prize money was awarded to French naval personnel until 1916. After that, amounts that would have been prize money went into a fund for naval widows and wounded.

Prize Money in the Dutch Republic

During the Dutch Revolt, William the Silent could issue letters of marque to privateers. By the late 1500s, five partly independent admiralties had formed. They were in charge of providing warships and acting as prize courts for their own warships and privateers. The Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company also issued Letters of Marque. The Admiralty of Zeeland handled the most privateer cases. Prizes were usually sold at auction. The large number of captures in the 1600s wars often lowered prices, meaning less prize money for crews.

Prize money was an important extra income for Dutch warship officers. A lieutenant-admiral usually received four times as much as the captain who made a capture. A vice-admiral received twice as much. These flag officers shared in all ships and goods captured by captains in their admiralty, even if they weren't there. For ordinary sailors, prize money was rare, small, and often delayed. Payments were sometimes made in installments over several years, and crew members often sold their future payments for much less than they were worth.

Privateering was already common when the Dutch Republic formed. It grew even more in the 1600s. Dutch privateers often tried to avoid the prize rules. They sometimes attacked neutral or even Dutch ships, didn't bring captures to court, or sold goods secretly to avoid paying duties. Privateers licensed by the Dutch India companies aggressively attacked ships they called "interlopers" in their areas, no matter their nationality.

During the Eighty Years' War, Dutch privateers mainly targeted Spanish and Portuguese ships. Privateers licensed by the West India Company were very active against ships trading with Brazil. After a treaty in 1661, privateers stopped attacking Portuguese ships. Many then started attacking English shipping during the Second and Third Anglo-Dutch wars. However, there was less Dutch privateering after the War of the Spanish Succession, as Dutch maritime activity generally declined.

Prize Money in the United States

Early Days (To 1814)

During the American Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress didn't have a strong navy. It relied heavily on privateers authorized by individual states to capture British ships. State Admiralty courts decided on the ownership and value of captured vessels. American privateers captured about 600 British merchant ships during this war. In 1787, the US Constitution gave the right to issue letters of marque to Congress.

At the start of the War of 1812, the few large US Navy ships were mostly inactive. The Royal Navy had limited resources in the western Atlantic, leaving the seas open for privateers on both sides. However, when US Navy frigates were put back into action, they had some impressive successes. Officers like Stephen Decatur and John Rodgers each received over 10,000 dollars in prize money. Later in the war, the Royal Navy blockaded the US Eastern seaboard, capturing US Navy vessels and merchant ships, and stopping American privateer activity.

From its beginning, the United States government gave naval personnel two types of extra payments:

- Prize money: A share of the money from captured enemy merchant ships and their cargo.

- Head money: A cash reward from the US Treasury for sinking enemy warships.

From 1791, US Navy personnel received half the money from a captured prize of equal or weaker strength. They received all the money if the captured vessel was stronger. Privateers, however, received all the money from any prize, but had to pay duties (up to 40% during the War of 1812). Generally, half the net amount went to the privateer's owners, and half to the crew. From 1800, US Navy ships that sank an armed enemy ship received a bounty of twenty dollars for each enemy crew member. This was divided among the crew like other prize money.

Under US law from 1800, if navy ships captured a prize, the money was divided in specific ways.

- The captain(s) of the capturing vessel(s) received 10% of the prize money.

- The squadron commander received 5%. If the captain was operating alone, he received 15%.

- Naval lieutenants, marine captains, and sailing masters shared 10%.

- Chaplains, marine lieutenants, surgeons, pursers, boatswains, gunners, carpenters, and master's mates shared 10%.

- Midshipmen, junior warrant officers, and mates of senior warrant officers shared 17.5%.

- Various petty officers shared another 12.5%.

- This left 35% for the rest of the crew.

Any unclaimed prize money was kept by the Navy and Treasury to fund disability pensions.

Prize Money After 1815

For most of the time between the end of the War of 1812 and the start of the American Civil War, there wasn't much chance to earn prize money. When the Civil War began, the Confederate States issued about 30 commissions to privateers. These captured between 50 and 60 United States merchant ships. However, Abraham Lincoln declared that Confederate privateers would be treated as pirates. Also, European colonies closed their ports to sell prize vessels. This encouraged privateer owners to become blockade runners instead.

From 1861, US Navy ships engaged Confederate privateers and blockade runners. It was unclear if prize money would apply, as the US didn't recognize the Confederate States as a separate country. However, a revised law in 1864 stated that prize money rules would apply to all captures made by the United States. Over 11 million dollars in prize money was paid to US Navy personnel for captures during the Civil War. About one-third of the prize money was supposed to go to officers, but about half actually did. This was probably because it was hard to find enlisted men when payments were delayed.

In 1856, the Declaration of Paris was signed. This made privateering illegal for the 55 nations that signed it. The United States didn't sign it, partly because it felt that if privateering was abolished, then naval vessels shouldn't capture merchant ships either. However, the US agreed to follow the declaration during the American Civil War.

Changes were made to how prize money was shared in the US Navy in the 1800s, with the last change in 1864. This law kept the 5% award for squadron commanders (now also fleet commanders) and 10% for captains under a flag officer (or 15% for independent captains). It added new awards for division commanders and fleet captains. The biggest change was that the remaining prize money was divided among other officers and men based on their pay rates. This law also increased the bounty (head money) for destroying an enemy warship. It was $100 for each enemy crew member on a ship of equal or lesser force, or $200 for each crew member on a stronger enemy ship. This was divided among the US ship's officers and men like other prize money.

The US Navy was small, so privateering was seen as the main way to attack enemy trade. Until the early 1880s, American naval experts thought privateering was still a good option. But as the US Navy grew, this view changed.

In the Spanish–American War of 1898, neither the US nor Spain used privateers. However, the US Navy received what would be its last prize money payments for that war. Sailors who fought in the battles of Manila Bay and Santiago shared prize funds of $244,400 and $166,700, respectively. These were based on the estimated number of Spanish sailors and the value of salvaged ships.

End of US Prize Money

During the Spanish-American War in 1898, many Americans felt the US Navy was trying to profit too much from prize money and head money, even though the amounts were not huge. All awards of prize money and head money to US Navy personnel were abolished by a huge vote in Congress in March 1899, shortly after the war ended.

Sometimes it's claimed the US Navy last paid prize money in 1947. This refers to a specific case involving the USS USS Omaha and USS Somers (DD-381). In November 1941, before the US entered World War II, they stopped a German cargo ship called Odenwald. The Odenwald was trying to hide by sailing under the US flag and carrying illegal goods. Its crew tried to sink it, but the Omaha's crew managed to save it. The US was not at war with Germany at the time. After the war, the Odenwald's owners said its seizure was illegal. However, a court ruled in 1947 that because the crew tried to sink and abandon the ship, the Omaha's crew had "salvage rights." This meant they were rewarded for saving the ship, which was worth about 3 million dollars. The court clearly stated it was a case of salvage, not prize money.

The End of Prize Money

Privateers: A Fading Role

Privateers were most common in European waters during the 1600s and early 1700s, in wars involving Britain, France, and the Dutch Republic. They were also active outside Europe in the American War of Independence, the War of 1812, and colonial conflicts. However, between 1775 and 1815, their income dropped sharply. This was because it became much harder to capture enemy ships, partly due to more naval vessels competing for captures. Since equipping and manning ships for commerce raiding was expensive, privateering became less profitable.

The Declaration of Paris in 1856 made privateering illegal for the nations that signed it. This made it politically difficult for non-signatories, like the United States, to use privateers in future conflicts. Also, using new metal-hulled steamships for privateering brought new challenges, like maintaining complex engines and needing frequent refueling. After 1880, many countries started paying subsidies to build fast merchant ships that could be converted into armed merchant cruisers under naval control during wartime. These ships replaced the need for privateers, and no privateers were commissioned after the American Civil War.

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |