Ernest Everett Just facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

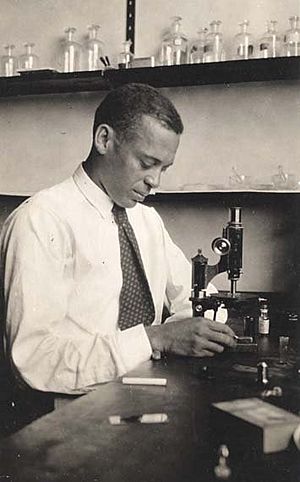

Ernest Everett Just

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 14 August 1883 |

| Died | 27 October 1941 (aged 58) |

| Resting place | Lincoln Memorial Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Dartmouth College University of Chicago |

| Known for | marine biology cytology parthenogenesis |

| Awards | Spingarn Medal (1915) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | biology, zoology, botany, history, and sociology |

| Institutions |

|

| Doctoral advisor | Frank R. Lillie |

Ernest Everett Just (born August 14, 1883 – died October 27, 1941) was an important African-American biologist and writer. He was one of the first scientists to show how important the outside surface of a cell is for how living things grow and develop.

Just studied marine biology (sea life), cytology (cells), and parthenogenesis (a type of reproduction). He believed scientists should study whole cells in their natural state. He thought it was better than just breaking them apart in a lab.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Ernest Just was born on August 14, 1883, in Charleston, South Carolina. He was one of five children. His father and grandfather were builders. When Ernest was four, both his father and grandfather died. His mother, Mary Matthews Just, had to support the family alone.

Mary taught at a school for African-American children in Charleston. In the summer, she worked in phosphate mines. She helped many Black families move to James Island to farm. The town they started was named Maryville in her honor.

When Ernest was young, he got very sick with typhoid fever. He had trouble getting better and his memory was affected. He had to relearn how to read and write. His mother helped him, but eventually gave up.

Ernest's mother wanted him to become a teacher. When he was 13, she sent him to a college in Orangeburg, South Carolina. But they both thought schools in the South were not as good for Black students. So, at 16, Ernest went north to Kimball Union Academy in Meriden, New Hampshire.

During his second year there, Ernest's mother died. Even with this sadness, he finished the four-year program in just three years. He graduated in 1903 with the best grades in his class.

Ernest then went to Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. He graduated in 1907 with very high honors. At Dartmouth, he became interested in biology, especially how eggs develop. He earned special awards in zoology, botany, history, and sociology.

Later, while teaching at Howard University, Just earned his PhD in 1916 from the University of Chicago. He was one of the first African Americans to get a doctorate from a major university.

Founding Omega Psi Phi

On November 17, 1911, Ernest Just and three students from Howard University started the Omega Psi Phi fraternity. The students were Edgar Amos Love, Oscar James Cooper, and Frank Coleman. They wanted to create the first Black fraternity on campus.

At first, Howard University's leaders were against the idea. They worried it might cause problems for the university's white administration. But Just helped to solve these issues. Omega Psi Phi, Alpha Chapter, officially started at Howard on December 15, 1911.

Scientific Career

After graduating from Dartmouth, Ernest Just faced a common problem for Black college graduates. It was very hard for Black people to get teaching jobs at white universities. So, Just took a job at Howard University in Washington, D.C., a historically Black university.

In 1907, he started teaching English. By 1909, he was also teaching biology. In 1910, he became the head of a new biology department. In 1912, he led the new Department of Zoology until he died in 1941.

Soon after starting at Howard, Just met Frank R. Lillie. Lillie was the head of zoology at the University of Chicago. He also directed the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Lillie invited Just to work as his research assistant at the MBL in the summer of 1909.

At the MBL, Just studied the eggs of sea creatures called invertebrates. He looked at how they were fertilized and how they reproduced. For over 20 years, Just spent almost every summer at the MBL.

Just became very skilled at handling marine eggs and embryos. Other scientists, both new and experienced, often asked for his help. In 1915, Just took time off from Howard to study at the University of Chicago. That same year, he received the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP. This award recognized his scientific achievements.

By the time he got his PhD in zoology in 1916, he had already published many research papers. He was known as a careful and skilled experimenter. He explored topics like how cells divide and how they react to light.

However, Just was frustrated because he couldn't get a job at a major American university. He wanted a position that would let him focus more on his research. Racism made it hard for him to get the opportunities he deserved.

Despite these challenges, Just made important contributions. In 1924, he helped write a textbook called General Cytology. In 1929, he traveled to Naples, Italy, to do experiments at a famous zoological station. In 1930, he was the first American invited to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin-Dahlem, Germany. Many Nobel Prize winners worked there.

Just visited Europe more than ten times between 1929 and 1938. Scientists there treated him with respect and encouraged his ideas. He enjoyed working in Europe because he faced less discrimination than in the U.S.

When the Nazis took control in Germany in 1933, Just stopped working there. He moved his studies to Paris and a marine lab in Roscoff, France.

Just wrote two books: Basic Methods for Experiments on Eggs of Marine Animals (1939) and The Biology of the Cell Surface (1939). He also published at least 70 scientific papers. He discovered how to quickly prevent too many sperm from fertilizing an egg. He also showed how the sticky properties of early embryo cells depend on their stage of development.

He believed that lab experiments should be as close to natural conditions as possible. His work on eggs helped scientists understand how cells respond to different signals. He strongly argued that the outer part of the cell, called the "ectoplasm," was key to how cells work. Sadly, his ideas were often overlooked, especially by American scientists.

Personal Life

On June 12, 1912, Ernest Just married Ethel Highwarden, who taught German at Howard University. They had three children: Margaret, Highwarden, and Maribel. They divorced in 1939. That same year, Just married Hedwig Schnetzler, a philosophy student he met in Berlin.

Death

When World War II started, Just was working in Roscoff, France. He was researching a paper called Unsolved Problems of General Biology. The French government asked foreigners to leave, but Just stayed to finish his work.

In 1940, Germany invaded France, and Just was briefly held in a prisoner-of-war camp. With help from his second wife's family and the U.S. State Department, he returned to the U.S. in September 1940. Just had been sick for months before being held, and his health worsened. In the fall of 1941, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and died soon after.

Legacy

Ernest Everett Just's life was told in the 1983 book Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just by Kenneth R. Manning. This book won an award and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. In 1996, the U.S. Postal Service honored Just with a special stamp.

Since 2000, the Medical University of South Carolina has held an annual event called the Ernest E. Just Symposium. This event encourages non-white students to study science and health. In 2008, a symposium honoring Just was held at Howard University, where he taught for many years.

The American Society for Cell Biology has given an award and hosted a lecture in Just's name since 1994. Both the University of Chicago and Dartmouth College, where Just studied, have also created awards or events in his honor. In 2013, an international symposium for Just was held in Naples, Italy, where he had worked.

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Just in his list of the 100 Greatest African Americans. A children's book about Just, called The Vast Wonder of the World: Biologist Ernest Everett Just, was published in 2018.

Just believed that life comes from a mix of chemicals that act in special ways. He wrote that "life is the harmonious organization of events." He thought that living things are more than just the sum of their tiny parts.

See also

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |