Aboriginal title in the United States facts for kids

The United States was the first country to recognize a special idea called aboriginal title. This means that Native American tribes and nations have rights to land they have used and lived on for a very long time. It's also known as "original Indian title" or "Indian right of occupancy."

To have aboriginal title, a tribe must show they have used and lived on the land continuously and exclusively for a "long time." Sometimes, individuals can also claim aboriginal title if their ancestors held the land this way. Unlike in some other places, the rights that come with aboriginal title are not limited to just old ways of using the land.

However, land with aboriginal title cannot be sold or given away by the tribes themselves, unless it's to the federal government or with Congress's approval. This is different from land Native Americans own like regular property (called "fee simple") or land held in federal trust.

The US Congress has the power to end aboriginal title, either by buying the land or by taking it (like through conquest). This ending of title doesn't always mean the tribes get paid under the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution, but many laws do offer payment. If aboriginal title hasn't been ended, tribes can sue to get their land back or for damages if someone has trespassed on it. Many lawsuits by tribes have been settled with new laws that end the aboriginal title in exchange for money or permission to run casinos.

Big lawsuits for money started in the 1940s, and lawsuits to get land back started in the 1970s. It's hard to sue the federal government to get land back because of "sovereign immunity" (meaning the government can't be sued without its permission). It's also hard to sue states for land or money, unless the federal government gets involved. The US Supreme Court has rejected most legal defenses against these claims. However, one court (the Second Circuit) has said that very old claims that would cause too much disruption might not be allowed.

Contents

History of Aboriginal Title

Before the United States Existed

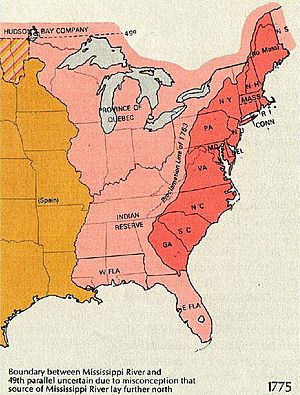

Before 1763, during the time of the American colonies, people often bought land directly from Native Americans. Many of the oldest land records in the Eastern states show these kinds of deals.

Things changed with the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This rule said that only the British Crown (the government) could buy land from Native Americans. It also tried to stop colonists from settling west of the Appalachian Mountains. The Declaration of Independence, which announced America's freedom from Britain, even complained about this rule.

After Independence, Before the Constitution

After the American Revolution, the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783 said that aboriginal title could not be ended without Congress's permission. But during this time, some states, like New York, still bought land from tribes without federal approval. Later, in the 1970s and 1980s, courts decided that the Confederation Congress didn't have the power to stop states from buying land within their own borders. So, the rule only applied to federal lands.

After the US Constitution

When the Constitution of the United States was approved in 1788, states lost the power to end aboriginal title. The Constitution gave the federal government control over trade with Native American tribes. Congress then passed laws called the Nonintercourse Acts (starting in 1790) that made it illegal to buy land from tribes without federal approval.

Early Supreme Court Decisions

The Marshall Court (1801–1835), led by Chief Justice John Marshall, made some of the first important decisions about aboriginal title. However, what the Court said about aboriginal title during this time was often "dicta," meaning it was comments that weren't directly part of the main ruling.

Two important cases, Fletcher v. Peck (1810) and Johnson v. M'Intosh (1823), were about land sales. In these cases, the Court said that aboriginal title could only be sold to the government.

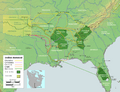

Indian Removal Era

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 led to many Native American tribes being forced to move from their lands in the Eastern United States. This policy resulted in the complete ending of aboriginal title in many states, including Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Illinois, Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Indiana, and Ohio by the 1840s.

Reservations and Treaties

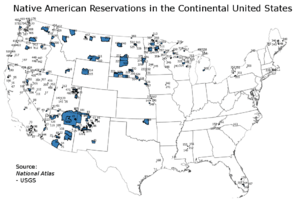

After the removal era, the policy shifted. All tribal lands were either given to the federal government or set aside as Indian reservations. This happened across the Western United States by the late 1800s. It took much less time to acquire land in the West than it did in the East.

In 1871, Congress stopped making treaties with Native American tribes. However, similar agreements continued to be used to take tribal land and set up reservation boundaries.

Later, the Dawes Act of 1887 divided communal reservation lands into smaller plots for individual Native Americans. Any "extra" land was then sold to non-Native people. This policy ended in 1934.

Modern Era (1940s—Present)

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (1971) ended all aboriginal title in Alaska. Similar laws, called Indian Land Claims Settlements, ended aboriginal title in Rhode Island (1978) and Maine (1980).

Since the 1940s, many Native American tribes have tried to get their land back or receive payment for land that was taken unfairly. They have worked with Congress, courts, and government agencies to resolve these claims. Many of these efforts have been successful, leading to court decisions or special agreements made through new laws.

What is Aboriginal Title?

How is it Recognized?

To recognize aboriginal title in the United States, a group must show they have used and lived on the land continuously and exclusively for a "long time." This "long time" can sometimes be as short as 30 years. However, if multiple tribes shared the same area, it might be harder for one tribe to claim exclusive aboriginal title.

Sometimes, individuals can also claim aboriginal title if their ancestors held the land individually, not as part of a tribe.

What Can You Do with Aboriginal Title Land?

If a tribe's land was taken away and they buy it back, it doesn't automatically become "Indian Country" again for tribal self-governance. States can still tax and enforce laws on these lands, even if a tribe reacquires them. Also, Native Americans cannot tax non-Native people who own land within their traditional areas.

How is Aboriginal Title Ended?

Today, for aboriginal title to be ended, it must be done by Congress or a part of the federal government that Congress has given permission to. The earliest and most common way to end aboriginal title was through treaties. Even if a treaty was made unfairly, it might still end aboriginal title if the tribe doesn't challenge it in court.

Since 1790, states have not been able to end aboriginal title. They can't even take tribal lands for unpaid taxes. However, if a state ended aboriginal title before 1790 (between independence and the Constitution), those actions are usually considered valid.

A famous court case, Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock (1903), said that Congress had complete power to end aboriginal title, even if it went against treaties. While this decision hasn't been officially overturned, later decisions have made it clear that the federal government has a special responsibility (a "fiduciary duty") to Native American tribes.

Ending aboriginal title means that any past trespassing or taking of resources from those lands is made legal, and tribes usually can't get compensation for those actions.

Lawsuits for Land and Money

For a long time, the idea of aboriginal title was mostly talked about in court cases that didn't involve Native Americans directly. It was assumed that tribes could sue to get their land back, but this wasn't really tested until the 1970s.

In 1974, a case called Oneida I said for the first time that federal courts could hear lawsuits from tribes trying to get their land back based on aboriginal title. Then, in 1985, Oneida II said that tribes could sue based on federal common law (laws made by judges). This case also said there was no time limit for these kinds of lawsuits, which meant the Oneida tribe could challenge a land deal from 1795!

These decisions opened the door for many important land claims, especially in the original thirteen colonies, where states had bought tribal land without federal approval after the Constitution was passed.

To sue, a tribe must prove that it is the direct descendant of the historical tribe. If a jury decides a group is not a tribe, then non-federally recognized tribes cannot automatically reverse that decision.

Getting Paid for Land

Under the Constitution

The Supreme Court has said that if the federal government takes land that Native Americans own like regular property (fee simple) or land recognized by a treaty, they must pay for it under the Fifth Amendment. However, the Court decided in Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v. United States (1955) that unrecognized aboriginal title is not "property" under the Fifth Amendment. This means it can be ended without payment. But if the government takes "recognized Indian title," tribes can claim payment.

Under Other Laws

The Nonintercourse Act created a special relationship between tribes and the federal government, like a trust. The Indian Claims Commission Act of 1946 (ICCA) created a way for tribes to sue the federal government for unfair dealings. This means tribes could get money if the government didn't act fairly, even if the land transfer was technically legal.

Before 1946, Native American land claims were usually not allowed in special claims courts. The ICCA created the Indian Claims Commission to handle these claims, but it also set a four-year time limit to file them. The Commission could only award money, not return land. Also, the ICCA was the only place to sue the federal government for these claims.

In these claims, the land's value is usually based on its value at the time it was taken, not its current value, and without interest.

Challenges to Lawsuits

Government Immunity

It's hard to sue the federal government because it has "sovereign immunity," meaning it can't be sued without its permission. The government has allowed some lawsuits for money under the ICCA, but with time limits.

Most illegal land takings happened at the hands of states. However, states also have "sovereign immunity" under the Eleventh Amendment to the United States Constitution. This means tribes generally cannot sue states without their permission.

There are a few exceptions:

- Tribes can sometimes sue state officials (not the state itself) to stop future illegal actions.

- The federal government can sue states on behalf of tribes. This is how the Coeur d'Alene Tribe got help in their claim for Lake Coeur d'Alene.

Delays in Bringing Claims

In the Oneida II case, the Supreme Court said there was no time limit for federal lawsuits to get land back based on aboriginal title. This means that aboriginal title generally cannot be lost just because someone else has lived on the land for a long time (called "adverse possession"). However, if a tribe was subject to an "Indian Termination Act," state time limits might apply to their land claims.

A legal idea called "laches" can sometimes be used to stop very old claims. This means that if a claim is so old that it would cause too much disruption or unfairness to current landowners, a court might not allow it. The Second Circuit court has used this idea to block some "disruptive" Native American land claims, even though other courts have not always agreed with this broad use of "laches."

Aboriginal Title and Reservations

Aboriginal title is different from "recognized Indian title." Recognized title is when the US federal government officially recognizes tribal land through a treaty or other agreement. Aboriginal title is not required to have recognized title.

The connection between aboriginal title and reservations can be confusing. Sometimes, courts don't need to decide if aboriginal title exists if the land is already part of an Indian reservation. Some reservations were created in a way that ended aboriginal title. While Congress can give tribes land as regular property, some reservations might still be held under aboriginal title.

In the past, it was thought that if aboriginal title was ended, all tribal rights to that land were also ended. But now, the view is that certain rights, like the right to use the land for hunting or fishing (called "usufructory rights"), might continue even if aboriginal title is ended.

Images for kids

-

Removal of the Five Civilized Tribes

-

ANCSA created Alaska Native Regional Corporations.

See Also

- Aboriginal title in the United States case law

- Indian Country

- Indian reservation

- Indian Land Claims Settlements

- Native American land claims

- Native American tribal sovereignty

- Native Americans in the United States

- Trust law

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |