Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Argued October 23, 1902 Decided January 5, 1903 |

|

| Full case name | Lone Wolf, Principal Chief of the Kiowas, et al., v. Ethan A. Hitchcock, Secretary of the Interior, et al.' |

| Citations | 187 U.S. 553 (more)

23 S. Ct. 216; 47 L. Ed. 299

|

| Prior history | 19 App. D. C. 315 |

| Holding | |

| Congress has plenary power to abrogate treaty obligations between the United States and Native American tribes unilaterally. | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | White, joined by Brewer, Brown, Fuller, Holmes, Peckham, McKenna, Shiras |

| Concurrence | Harlan |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Constitution, Article V | |

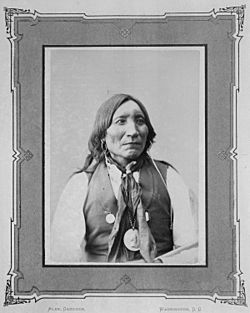

Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553 (1903), was an important case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States. It was brought by Lone Wolf, a chief of the Kiowa tribe. He sued the United States government.

Lone Wolf claimed that the government had unfairly taken land from Native American tribes. This land was protected by the Medicine Lodge Treaty. He said that actions by Congress went against this treaty.

The Supreme Court decided that Congress had "plenary power". This meant Congress had full authority to change or cancel treaties with Native American tribes on its own. This decision was a big change from earlier rulings. Cases like Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832) had shown more respect for the independence of Native American tribes.

Contents

Understanding the Background

Native American Tribes

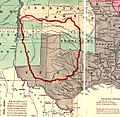

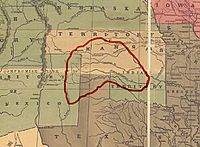

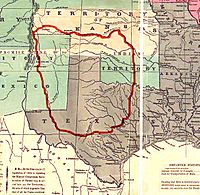

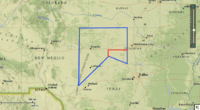

The Kiowa are a Native American tribe. Historically, they lived in the southern Great Plains. This area is now parts of Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas, and New Mexico. They originally lived further north near the Platte River. Due to pressure from other tribes, they moved south. They settled mainly in what is now Oklahoma, south of the Arkansas River.

The Kiowa had a long history of working closely with the Plains Apache. Around 1790, the Kiowa also formed an alliance with the Comanche. Together, they created a strong barrier. This made it hard for European-Americans to enter their lands. Travel on the Santa Fe Trail became dangerous. Attacks on wagon trains started in 1828 and continued for years.

Important Treaties

In 1837, Kiowa leaders signed their first treaty with the United States at Fort Gibson. By 1854, a new treaty was needed. The U.S. signed a treaty with the Kiowa, Comanche, and Kiowa-Apache (KCA) at Fort Ackinson, Indian Territory. This treaty mostly extended the 1837 agreement.

There was an attempt to move some tribes to a reservation on the Brazos River in Texas. This was near Fort Belknap. By 1858, the plan changed to move the reservation into Indian Territory. By August 1859, the tribes from the Brazos Reservation were moved. They settled south of the Washita River near Fort Cobb.

In 1865, near present-day Wichita, Kansas, the three tribes signed another treaty. This treaty set up a reservation in parts of Oklahoma and Texas. Finally, in 1867, the tribes agreed to the Medicine Lodge Treaty. This treaty created a much smaller reservation. It also stated that white settlers were not allowed on the reservation. To reduce the land further, three-fourths of the tribal members had to agree.

Changes to Tribal Life

Within a year, the United States broke the Medicine Lodge Treaty. General William Tecumseh Sherman ordered all tribes to Fort Cobb. He held back treaty payments. He also tried to end their hunting rights. At the same time, government agents tried to weaken tribal leaders. White hunters were also killing off the buffalo herds. This made it harder for the tribes to live as they always had.

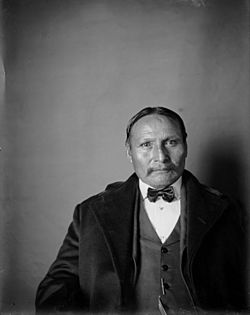

Two new leaders became important: Quanah Parker and Lone Wolf (the younger). After a defeat at the Battle of Palo Duro Canyon, Parker decided to adopt some white ways. Lone Wolf and his followers, however, continued to resist these changes. Many older tribal leaders were arrested or died from old age and disease.

During this time, the KCA tribes found a new way to use their land. They leased it to cattle ranchers for grazing. By 1885, about 1.5 million acres were used for about 75,000 cattle. The tribes received $55,000 each year. Meanwhile, white settlers often came onto the reservation. They took timber and other resources. The tribes formed a police force to protect their property.

The Jerome Commission's Visit

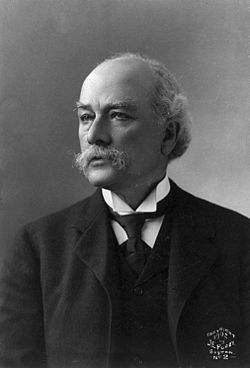

In 1892, the United States sent the Jerome Commission. This group included David H. Jerome, Alfred M. Wilson, and Warren G. Sayre. Their goal was to convince the Kiowa to give up most of their reservation land. In return, the tribes would get $2 million.

Lone Wolf spoke strongly against this plan. He said:

Now we have several good schools on the reservation. We intend to send our children there. They will learn how to live like white people and become civilized. We told our people to build houses, and many are doing so. Because we are making such fast progress, we ask the commission not to push us too quickly. This morning, the Comanches, Kiowas, and Apaches all decided not to sell the country. I do not wish the commission to force us. That is all.

After more than a week of talks, terms were set. Each tribal member would receive 160 acres. The tribes would get $2 million. Of this, $250,000 would be paid to members. The rest would be held in trust for the tribes, earning 5% interest.

The commission quickly began collecting signatures. But soon, there were claims of fraud. Joshua Givens, an interpreter, was suspected of being dishonest. He was accused of forcing some members to sign. Others were tricked into thinking they were signing against the agreement. The tribes almost all opposed the agreement. They asked to see the document and remove their signatures. Lone Wolf later said they were refused and threatened. Jerome left the reservation claiming he had the approval of three-fourths of the tribe.

Congress and the Agreement

Because the agreement's validity was questioned, the tribes worked with the Indian Rights Association (IRA). Local ranchers also joined them. They all lobbied against Congress approving the agreement. The IRA wrote to Senators. They said the agreement was "utterly destructive of that honor and good faith." They argued it was wrong to treat a weaker people this way.

The United States Secretary of the Interior told Congress the land was not good for farming. He said the small amount of land given would not be enough for the tribes to raise cattle. He warned the agreement would harm the tribes. A bill to approve the agreement was introduced in 1892. It failed to pass. It was brought up every year until it finally passed in 1900, eight years later. The agreement passed when the Rock Island Railroad agreed to set aside an extra 480,000 acres of pastureland for the tribes to share.

Court Challenges

When the agreement was approved, tribal leaders went to Washington, D.C.. They asked to meet with President William McKinley. President McKinley said the tribes had to accept Congress's decision. Quanah Parker and other chiefs accepted that the fight was over. But Lone Wolf kept arguing against the land division. In 1901, Lone Wolf and others hired William M. Springer, a former federal judge.

District of Columbia Court

On June 6, 1901, Springer filed a lawsuit. This was in the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia. This is a different court from the U.S. Supreme Court. The plaintiffs asked the court to stop the government. They wanted to prevent the KCA lands from being opened to settlers. They also wanted to stop the land from being divided.

Springer argued that the Jerome agreement took the tribes' land without due process. He said it broke the treaty and violated the Constitution. Springer claimed the KCA were tricked into signing. He also said it was not signed by three-fourths of the members, as the treaty required. He stated that the tribes had protested from the start. He also said the version Congress approved was different from the one the KCA signed.

While the case was being heard, on August 6, 1901, the government began selling the tribes' extra land. Judge A.C. Bradley ruled against Lone Wolf. He said Congress had the power to divide the land. He referred to the case United States v. Kagama.

Appeals Court Decision

Springer then appealed to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. By the time this court heard the appeal, the reservation land had already been divided. The extra land had been sold.

The D.C. Circuit Court ruled that the question was not for the courts to decide. They called it a "political question" that Congress had to decide. The court said that an act of Congress must be stronger than any specific part of a treaty with a Native American tribe. The court also said that the land did not truly belong to the tribe. It was controlled by the United States, and the Native Americans were just living on it. The appeals court agreed with the lower court's decision.

The Supreme Court's Ruling

Arguments Presented

At this point, the IRA hired a new lawyer, Hampton L. Carson. He took over from Springer. The arguments were the same as in the lower courts. They argued that the tribes were losing their land without fair legal process. The lawyers pointed out that the U.S. had never taken a tribe's land without some form of agreement from the tribe before. Carson and Springer used the case Worcester v. Georgia in their arguments. They also mentioned the "Indian canon of construction." This is a rule that says treaties with Native Americans should be interpreted in a way that benefits the tribes.

Willis Van Devanter argued the case for the United States. He said that Congress had the power to cancel the treaty whenever it wanted. Devanter used Kagama as proof that Congress had full power over Native American matters.

The Court's Opinion

Justice Edward Douglass White wrote the opinion for the unanimous court. The Court decided that Congress had the power to cancel treaty agreements with Native American tribes. They said Congress had an "inherent plenary power." This means a complete and unquestionable power.

Justice White wrote:

Congress has always had authority over the tribal relations of the Indians. This power has always been seen as a political one. It is not something the courts can control.

The decision was partly based on the idea that the United States was like a parent to the tribes. The Court saw the tribes as dependent on the U.S. government.

Justice White also wrote that it was assumed the United States would act fairly. He said Congress would act like a "Christian people" dealing with an "ignorant and dependent race." This view reflected common beliefs of the time. It suggested that Congress would always act in the best interest of the tribes. White argued that requiring tribal consent might actually harm the tribes. He said tribes should trust that Congress would protect their needs.

Justice John Marshall Harlan agreed with the final decision. However, he did not write his own separate opinion.

What Happened After

Reports show that 90% of the land given to tribal members was lost to settlers. By the 1920s, the KCA tribes were very poor. Their unemployment rate was 60%.

By 1934, about 90 million acres of Native American lands had been transferred to settlers. This was about two-thirds of all Indian lands. The process of dividing and selling tribal lands continued. It only stopped when the Meriam Report was published. This report showed how damaging the policy was. By the time Congress ended this land division, the KCA land went from 2.9 million acres to about 3,000 acres.

The Court's ruling also meant that Native American tribes had few options to resolve land disputes. They could only go to Congress. They could not bring cases in the United States Court of Claims. They were limited to state courts, which were often not friendly to their claims.

Many legal experts have criticized the Lone Wolf decision. Some have even compared it to the very controversial Dred Scott case.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |