Medicine Lodge Treaty facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

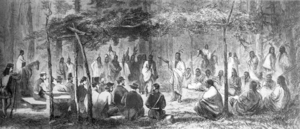

Council at Medicine Lodge Creek, drawing from Harper's Weekly

|

|

| Signed | 21 October 1867 28 October 1867 |

|---|---|

| Location | Medicine Lodge Peace Treaty Site |

| Signatories | |

| Citations | 15 Stat. 581 15 Stat. 589 15 Stat. 593 |

| See also the Act of 6 June 1900, §6, 31 Stat. 672, 676. | |

The Medicine Lodge Treaty is the name for three important agreements. These were signed in October 1867 near Medicine Lodge, Kansas. They were made between the United States government and several southern Plains Indian tribes. The goal was to bring peace by moving Native Americans to special areas called reservations. This would keep them separate from European-American settlers.

A group called the Indian Peace Commission helped negotiate these treaties. In their report, they said that the wars could have been avoided. They found that the U.S. government had not always been fair or honest with Native Americans. They also failed to keep their promises.

The U.S. government and tribal leaders met at a place important for Native American ceremonies. The first treaty was signed on October 21, 1867, with the Kiowa and Comanche tribes. The second treaty, with the Kiowa-Apache, was signed on the same day. The third treaty was signed on October 28 with the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes.

Under these treaties, the tribes were given smaller reservations than before. The treaties said that adult men in the tribes needed to vote to approve them. However, this vote never fully happened. Later, the U.S. government passed new laws like the Dawes Act. These laws allowed the government to reduce reservation lands even more.

Because of these issues, the Kiowa chief Lone Wolf sued the government. He said the government had acted unfairly. In 1903, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the tribes. The Court said that Congress had "plenary power" (full authority) to make such decisions. After this, Congress often made land decisions for other reservations without tribal agreement.

Years later, in the mid-1900s, the Kiowa, Arapaho, and Comanche tribes sued the U.S. government again. They won large amounts of money as compensation for the land taken.

Contents

The Indian Peace Commission

In 1867, the United States Congress created the Indian Peace Commission. Its job was to make peace with the Plains Indian tribes who were fighting the U.S. The Commission met in St. Louis, Missouri, on August 6, 1867. They chose Nathaniel Green Taylor, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, as their leader.

The Commissioners agreed on a plan for lasting peace. They wanted to separate "hostile" (unfriendly) Indians from "friendly" ones. They also planned to move all tribes to reservations. These reservations would be away from the paths of U.S. settlers moving west. The government would also provide for the tribes' needs.

The Commission sent a report to the President on January 7, 1868. This report explained the causes of the Indian Wars. It listed many unfair social and legal actions against Native Americans. It also mentioned broken treaties and dishonest local agents. The report stated that Congress had failed to meet its legal duties.

The report concluded that the Indian Wars could have been prevented. This would have happened if the U.S. government had acted honestly and legally.

Other important members of the Peace Commission included Lieutenant General William Tecumseh Sherman. He was a military commander. Major General William S. Harney also joined, having fought with the Cheyenne and Sioux before. Brigadier General Alfred Terry was another military leader.

Senator John B. Henderson of Missouri was also a member. He helped create the peace commission. Colonel Samuel F. Tappan was a peace supporter. He had investigated the Sand Creek massacre. Major General John B. Sanborn had helped negotiate an earlier treaty in 1865. General Sherman could not attend the councils at Medicine Lodge Creek. Major General Christopher C. Augur took his place temporarily.

Meetings at Medicine Lodge River

After a meeting with northern Plains Indians in September, the Commission gathered. They met at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas in early October. From there, they traveled by train to Fort Harker.

An escort of 500 soldiers from the 7th Cavalry Regiment joined them. These soldiers had two powerful Gatling guns. Many newspaper reporters also came along. They wrote detailed stories about the Commission's work.

The Commission arrived at Fort Larned on October 11. Some chiefs were already there. These included Black Kettle of the Cheyenne, Little Raven of the Arapaho, and Satanta of the Kiowa.

The tribes asked to move the meetings to Medicine Lodge River. This was a traditional Native American ceremonial site. Preliminary talks began on October 15. They discussed an earlier military action by Major General Winfield Scott Hancock. During this action, a large Cheyenne and Sioux village was destroyed. The Commissioners agreed that this action was a mistake. They apologized for the destruction. This helped create a more positive mood for the main meetings. The councils officially began on October 19.

Treaty Terms and Signatories

The treaties signed at Medicine Lodge Creek were very similar. The tribes had to give up their large traditional lands. In return, they received much smaller reservations in Indian Territory (which is now Oklahoma). They also received supplies like food, clothing, tools, and weapons for hunting.

Treaties with the Kiowa, Comanche, and Plains Apache

The first treaty forced the Kiowa and Comanche to give up over 60,000 square miles of their land. They received a 3-million-acre reservation in the southwest part of Indian Territory. This land was mostly between the North Fork of the Red River and the North Canadian River. The tribes were also promised houses, barns, and schools worth $30,000, even though they had not asked for them.

A second treaty included the Plains or Kiowa-Apache tribe. This treaty was signed by the same Kiowa and Comanche chiefs, plus several Plains Apache chiefs. These treaties with the Kiowa, Comanche, and Plains Apache tribes were completed on October 21, 1867.

Kiowa chiefs who signed:

- Satank, or Sitting Bear

- Sa-tan-ta, or White Bear

- Wa-toh-konk, or Black Eagle

- Ton-a-en-ko, or Kicking Eagle (Kicking Bird)

- Fish-e-more, or Stinging Saddle

- Ma-ye-tin, or Woman's Heart

- Sa-tim-gear, or Stumbling Bear

- Sit-par-ga, or One Bear

- Cor-beau, or The Crow

- Sa-ta-more, or Bear Lying Down

Comanche chiefs who signed:

- Parry-wah-say-men, or Ten Bears

- Tep-pe-navon, or Painted Lips

- To-sa-in (To-she-wi), or Silver Brooch

- Cear-chi-neka, or Standing Feather

- Ho-we-ar, or Gap in the Woods

- Tir-ha-yah-gua-hip, or Horse's Back

- Es-a-nanaca, or Wolf's Name

- Ah-te-es-ta, or Little Horn

- Pooh-yah-to-yeh-be, or Iron Mountain

- Sad-dy-yo, or Dog Fat

Plains Apache chiefs who signed:

- Mah-vip-pah, Wolf's Sleeve

- Kon-zhon-ta-co, Poor Bear

- Cho-se-ta, or Bad Back

- Nah-tan, or Brave Man

- Ba-zhe-ech, Iron Shirt

- Til-la-ka, or WhiteHorn

At this meeting, the Comanche Chief Parry-wah-say-men (Ten Bears) gave a powerful speech. He spoke about the future of his people:

My heart is filled with joy when I see you here, as the brooks fill with water when the snow melts in the spring; and I feel glad, as the ponies do when the fresh grass starts in the beginning of the year. I heard of your coming when I was many sleeps away, and I made but a few camps when I met you. I know that you had come to do good to me and my people. I looked for benefits which would last forever, and so my face shines with joy as I look upon you. My people have never first drawn a bow or fired a gun against the whites. There has been trouble on the line between us and my young men have danced the war dance. But it was not begun by us. It was you to send the first soldier and we who sent out the second. Two years ago I came upon this road, following the buffalo, that my wives and children might have their cheeks plump and their bodies warm. But the soldiers fired on us, and since that time there has been a noise like that of a thunderstorm and we have not known which way to go. So it was upon the Canadian. Nor have we been made to cry alone. The blue dressed soldiers and the Utes came from out of the night when it was dark and still, and for camp fires they lit our lodges. Instead of hunting game they killed my braves, and the warriors of the tribe cut short their hair for the dead. So it was in Texas. They made sorrow come in our camps, and we went out like the buffalo bulls when the cows are attacked. When we found them, we killed them, and their scalps hang in our lodges. The Comanches are not weak and blind, like the pups of a dog when seven sleeps old. They are strong and farsighted, like grown horses. We took their road and we went on it. The white women cried and our women laughed.

But there are things which you have said which I do not like. They were not sweet like sugar but bitter like gourds. You said that you wanted to put us upon reservation, to build our houses and make us medicine lodges. I do not want them. I was born on the prairie where the wind blew free and there was nothing to break the light of the sun. I was born where there were no inclosures [sic] and where everything drew a free breath. I want to die there and not within walls. I know every stream and every wood between the Rio Grande and the Arkansas. I have hunted and lived over the country. I lived like my fathers before me, and like them, I lived happily.

When I was at Washington the Great Father told me that all the Comanche land was ours and that no one should hinder us in living upon it. So, why do you ask us to leave the rivers and the sun and the wind and live in houses? Do not ask us to give up the buffalo for the sheep. The young men have heard talk of this, and it has made them sad and angry. Do not speak of it more. I love to carry out the talk I got from the Great Father [president of the US]. When I get goods and presents I and my people feel glad, since it shows that he holds us in his eye.

If the Texans had kept out of my country there might have been peace. But that which you now say we must live on is too small. The Texans have taken away the places where the grass grew the thickest and the timber was the best. Had we kept that we might have done the things you ask. But it is too late. The white man has the country which we loved, and we only wish to wander on the prairie until we die. Any good thing you say to me shall not be forgotten. I shall carry it as near to my heart as my children, and it shall be as often on my tongue as the name of the Great Father. I want no blood upon my land to stain the grass. I want it all clear and pure and I wish it so that all who go through among my people may find peace when they come in and leave it when they go out.—Ten Bears

Treaty with the Cheyenne and Arapaho

In an earlier treaty from 1865, the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes had a reservation. It included parts of Kansas and Indian Territory. Under the Medicine Lodge Treaty, their land was cut by more than half. It was reduced to about 4.3 million acres, all south of the Kansas state line.

The tribes were allowed to keep hunting buffalo north of the Arkansas River. This was permitted as long as buffalo were still there. They also had to stay away from white settlements and roads. This agreement helped get the Dog Soldiers (a Cheyenne warrior society) to agree to the treaty. A separate treaty was made for the Northern Cheyenne, but they did not sign it. They were allied with Red Cloud and the Oglala Lakota who were fighting the U.S.

Southern Cheyenne chiefs who signed:

- O-to-ah-nac-co, Bull Bear

- Moke-tav-a-to, Black Kettle

- Nac-co-hah-ket, Little Bear

- Mo-a-vo-va-ast, Spotted Elk

- Is-se-von-ne-ve, Buffalo Chief

- Vip-po-nah, Slim Face

- Wo-pah-ah, Gray Head

- O-ni-hah-ket, Little Rock

- Ma-mo-ki, or Curly Hair

- O-to-ah-has-tis, Tall Bull

- Wo-po-ham, or White Horse

- Hah-ket-home-mah, Little Robe

- Min-nin-ne-wah, Whirlwind

- Mo-yan-histe-histow, Heap of Birds

Arapaho chiefs who signed:

- Little Raven

- Yellow Bear

- Storm

- White Rabbit

- Spotted Wolf

- Little Big Mouth

- Young Colt

- Tall Bear

Unapproved Treaty

The Medicine Lodge Treaty was immediately met with disagreement. Many members and leaders of the tribes did not accept it. The treaty itself stated that 3/4 of the adult men in each tribe had to approve it. This approval, called ratification, never fully happened. So, the treaty was never officially valid or legal. Conflicts over the treaty terms continued for many years.

The Medicine Lodge Treaty also said that 3/4 of the adult men on the reservation had to approve any future land sales. In 1887, Congress changed its policy on Native American lands. They passed the Dawes Act. This law aimed to divide tribal land into smaller pieces for individual families. The government could then sell any "extra" land.

For the southern Plains Indians, a special group was sent to get their agreement for these land divisions and sales. The Jerome Agreement of 1892 was created. Even though the tribes never officially approved it, this agreement put the new land policy into action. This meant millions of acres were taken from the reservation. The commission that negotiated the agreement did not tell the Native Americans what the land would be sold for.

The Kiowa chief Lone Wolf sued the Secretary of the Interior. He sued on behalf of the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache tribes. He argued that the government had cheated them.

The case, Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1903, the Court made its decision. It agreed that the Native Americans had not agreed to give up the land. However, the Court ruled that Congress had "plenary power" (full authority) to act on its own. So, the tribes' disagreement did not matter. This decision showed the common view towards Native Americans in the 1800s. The Court even quoted an earlier case, describing tribes as "wards of the nation." This meant they were seen as dependent on the U.S. government, which had a duty to protect them, and therefore, power over them.

What Happened Next

After the Supreme Court's decision, Congress kept changing reservation lands without tribal agreement. This started in 1903 and 1904 with the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs, William Arthur Jones, said he planned to support bills in Congress that would take Indian property without their consent. For example, in 1907, Congress allowed the sale of "extra" land at Rosebud, again without the tribes' permission.

The issues from the Medicine Lodge Treaty were challenged again in the mid-1900s. Starting in 1948, representatives from the Kiowa, Apache, and Comanche tribes sued the U.S. government. They sought payment for the original treaty and later actions, including sales under the unapproved Jerome Agreement. Over many years and several lawsuits, the tribes won large amounts of money. They received tens of millions of dollars in compensation from the Indian Claims Commission.

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |