Indian Peace Commission facts for kids

The Indian Peace Commission was a special group created by the United States government on July 20, 1867. Its main goal was to "establish peace with certain hostile Indian tribes." This group included four regular citizens and three (later four) military leaders.

During 1867 and 1868, they talked with many Native American tribes. These included the Comanche, Kiowa, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Lakota, Navajo, and Bannock. The agreements they made were meant to move the tribes to special areas called reservations. The government also wanted to help these native peoples change their way of life. They hoped tribes would switch from moving around (nomadic) to staying in one place and farming.

It's not clear if the tribes fully understood everything they agreed to. This was because of language and cultural differences. The Commission thought of tribes like a modern government with leaders who could make everyone follow rules. But Native American tribes made decisions by talking until everyone agreed. Chiefs were more like guides and advisors.

The Commission represented the U.S. Congress. However, Congress only paid for the talks, not for the promises made in the agreements. Once treaties were signed, the government was slow to act on some promises. They even rejected others. Even when treaties were approved, the promised help was often late or never given. Congress didn't feel forced to support what the Commission did. Eventually, in 1871, Congress stopped making treaties with tribes altogether.

Most people saw the Indian Peace Commission as a failure. Fighting started again even before the group officially ended in October 1868. The Commission sent two reports to the government. They suggested that the U.S. should stop seeing tribes as separate nations. They also said the U.S. should stop making treaties. The reports recommended using the army against tribes who refused to move to reservations. They also wanted to move the Bureau of Indian Affairs (which handled Native American issues) from the Department of the Interior to the Department of War. The system of treaties eventually fell apart. A decade of war followed the Commission's work. This was the last big commission of its kind.

Contents

Why the Commission Was Formed

During the 1860s, the American Civil War was happening. Many U.S. soldiers were fighting in the war. This meant the government had less control over the western parts of the country. Also, there was a lot of corruption in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. At the same time, more and more white settlers and railroads were moving west. All these things led to unrest and fighting.

A terrible event happened on November 29, 1864. It was called the Sand Creek massacre. U.S. troops killed over a hundred friendly Cheyenne and Arapaho people. Most of them were women and children. After this, the fighting got worse. Congress sent Senator James R. Doolittle to investigate. After two years, his report blamed the fighting on "lawless white men."

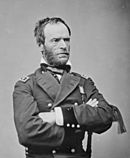

On December 21, 1866, another conflict happened. It was called the Fetterman Fight. Lakota, Sioux, and Arapaho warriors killed an entire army unit. This was part of Red Cloud's War. General William Tecumseh Sherman wrote to the Secretary of War. He said that even a few Native Americans could stop many soldiers. He believed action had to be taken, whether by talking or by fighting.

After four days of discussion, Congress created the Peace Commission on July 20, 1867. Its main goal was to "establish peace with certain hostile Indian tribes." They had three main aims to solve the "Indian question":

- To remove the reasons for war if possible.

- To protect frontier settlements and the building of railroads to the Pacific Ocean.

- To suggest a plan for helping Native Americans adopt a "civilized" way of life.

Fighting wars in the West was very expensive. Congress decided that peace was better than trying to wipe out the tribes. So, they gave power to a seven-man commission. This group included four civilians and three military officers. Their job was to talk with the tribes for the government. They were to try and get tribes to move to reservations. If they failed, they could raise an army to move them by force.

Commission Members

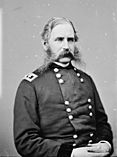

The members of the Commission included:

- Nathaniel Green Taylor: A former minister and head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

- John B. Henderson: A U.S. Senator who helped create the Commission.

- Samuel F. Tappan: A journalist and activist who supported Native American rights. He also investigated the Sand Creek Massacre.

- John B. Sanborn: A former major general in the U.S. Army.

- William Tecumseh Sherman: A high-ranking general in the U.S. Army.

- Alfred Terry: A major general in the U.S. Army.

- William S. Harney: A major general in the U.S. Army.

- Christopher C. Augur: A major general in the U.S. Army. He joined later.

Taylor, Tappan, Henderson, and Sanborn were named directly in the law that created the Commission. The president chose the military officers: Sherman, Terry, Harney, and later Augur.

The Commission's Work

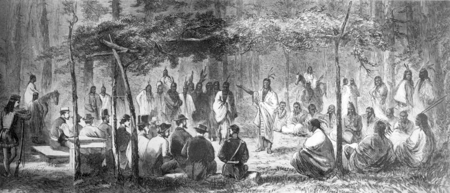

The Commission first met in St. Louis. They told military and civilian groups to start gathering tribes at Fort Laramie National Historic Site in the north and Fort Larned National Historic Site in the south. The Commission then traveled west. They met with leaders at Fort Leavenworth and other places. They also met with Lakota, Sioux, and Cheyenne groups. These early meetings didn't lead to any formal agreements. The commissioners planned to return later to talk more.

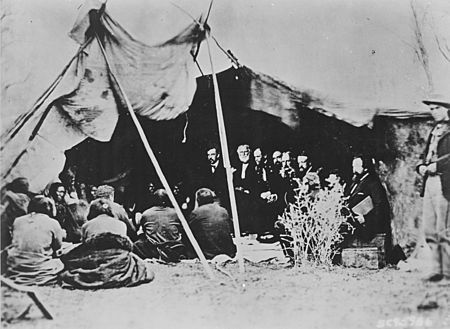

The Commission members went back to St. Louis. Then they traveled to Fort Larned, arriving on October 12, 1867. From there, they went to the Medicine Lodge River with an escort of local chiefs. The Commission itself had about 600 men and 1,200 animals with them. This group included reporters, soldiers, and many helpers like cooks and interpreters.

While on the way to Medicine Lodge, General Sherman was called back to Washington, D.C.. General Christopher C. Augur took his place.

Medicine Lodge Treaty

Talks began on October 19, 1867, at Medicine Lodge. About 5,000 people from the Comanche, Kiowa, Arapaho, and Kiowa-Apache tribes were camped there. For two days, the tribes resisted the idea of leaving their land. For example, Kiowa Chief Satanta said, "This building of homes for us is all nonsense. We don't want you to build any for us. We would all die."

On October 21, treaties were signed. These agreements moved the tribes to reservations in Oklahoma. The government promised small yearly payments and other things to help them switch to farming. In return, the commissioners gave them many goods and gifts.

On October 27, about 500 Cheyenne warriors arrived. They had been camped about 40 miles away. They also agreed to a similar treaty. This treaty created a reservation for them between the Arkansas River and Cimarron River (Arkansas River tributary) south of Kansas. More gifts were given, and the talks ended.

First Visit to Fort Laramie and Report

The Commission immediately left for North Platte and Fort Laramie. They hoped to talk with Red Cloud, a Lakota leader who was leading a revolt. But they only found the Crow people, who were already friendly with white settlers. Before leaving without success, they received a message from Red Cloud. He said that if the army left the forts on the Bozeman Trail, the war would end. The Commission sent a message back, suggesting a meeting in the spring or summer.

The commissioners went back to report to the government in December. Their report was submitted on January 7, 1868. In it, they described their successful talks. They also blamed white people for starting the recent conflicts. They urged Congress to approve the treaties and create areas where tribes could farm. They also wanted to replace "barbarous dialects" with the English language. They hoped that in 25 years, the buffalo (which many tribes relied on) would be gone. They believed nomadic Native Americans would become like other citizens, losing their tribal identity. The Commission hoped to prevent "another generation of savages." They also looked forward to talks with the Navajo people and the Sioux, with whom the government was still at war.

Treaty of Fort Laramie

In the new year, the Commission sent people to gather Lakota leaders at Laramie. President Ulysses S. Grant told General Sherman to prepare to leave military posts on Sioux land. This was the first time in history the U.S. government agreed to the demands of a hostile Native American leader in the field. The Commission arrived in Omaha, Nebraska in April. Sherman was again called back to Washington D.C. for other duties.

At Laramie, Red Cloud was not there. Talks began with the Brulé Lakota on April 13. The Commission agreed that the government would leave its military outposts. They would also build more Indian agencies and set aside land as "unceded Indian territory." The tribes agreed to similar rules as those at Medicine Lodge. These included staying on reservations and getting help to switch to farming.

Throughout the summer, many leaders signed the treaty. These included leaders of the Crow, Northern Cheyenne, and Northern Arapaho. But Red Cloud himself did not sign. He sent word that he would only come down from the mountains after the forts were abandoned. After the forts were left, Red Cloud and his warriors rode to them and burned them down. He then arrived at Fort Laramie in October. He talked for over a month and finally signed the treaty on November 6, 1868.

However, the Commission was not there to meet Red Cloud. In May, they had left Fort Laramie. They left the final signing of the treaty to the fort's commander. General Terry went to other forts. General Augur went to Fort Bridger to talk with the Snake, Bannock, and other tribes. Sherman, who had returned, went with Tappan to Fort Sumner to meet the Navajo. Only Harney and Sanborn stayed at Fort Laramie for a short time before joining Terry.

Treaty of Bosque Redondo

Sherman and Tappan arrived at Fort Sumner near Bosque Redondo on May 28, 1868. In 1864, thousands of Navajo people had been forced to move there. This was after U.S. soldiers used "scorched earth" tactics, which meant destroying everything. Many Navajo were pushed to the edge of starvation. On their journey, about 3,000 died in what became known as the Navajo's Long Walk.

Once they arrived at the camp, conditions were very bad. Farming was almost impossible. Other tribes raided their animals, and their crops failed due to dry weather, floods, and pests. They had to rely on government food, and many died from sickness and hunger. Even with such poor conditions, the camp was very expensive for the government to keep running.

Sherman wanted to move the Navajo to the Indian Territory in Oklahoma. But Tappan wanted them to return to their homeland in the Four Corners region. Sherman could not convince the Navajo, led by Barboncito. The Navajo decided they would not stay or move further east unless they were forced.

The two commissioners eventually presented a treaty. This treaty would allow the Navajo to return to their homeland. It also promised government help, required their children to go to school and learn English, and provided tools and encouragement for farming. On June 18, 1868, about 8,000 Navajo, with their sheep and horses, began their "Long Walk Home" to their ancestral lands. They traveled about 12 miles each day.

Fort Bridger Treaty

At Fort Bridger in modern Wyoming, General Augur met with the Shoshone and Bannock tribes. Even though they were at peace with the government, a treaty was signed on July 3, 1868. The goal was to "arrange matters that there may never hereafter be a cause of war between them." This treaty moved the tribes to the Fort Hall Indian Reservation and Wind River Indian Reservation. It also included rules very similar to the other agreements the Commission had made.

Final Report

In October, the commissioners returned to Chicago. The agreements at Medicine Lodge had already started to fail. Red Cloud had not yet signed for his group of Lakota. Senator Henderson was busy with the process to remove President Andrew Johnson from office. So, the remaining seven commissioners wrote their final report. It was published on October 9, 1868.

They recommended that the government provide the promised supplies to the tribes who had moved to reservations. They also said that each treaty should be fully in effect, even if the Senate had not officially approved it. They suggested that the government stop seeing tribes as separate nations. They also said no more treaties should be made with them. Finally, they recommended that "military force should be used to compel the removal" of any Native Americans who refused to go to reservations. They also suggested moving the Bureau of Indian Affairs from the United States Department of the Interior to the United States Department of War.

The Commission officially ended on October 10, 1868. It was the last major commission of its kind.

Treaty Promises

The Commission and Congress clearly wanted to "civilize" Native American peoples. According to Eric Anderson of Haskell Indian Nations University, the first treaty at Medicine Lodge marked a change. It moved from trying to wipe out tribes to policies that aimed to destroy their culture.

Senator Samuel C. Pomeroy believed that Native Americans had to join "civilization" or face "extinction."

Historian Francis Paul Prucha described Nathaniel Taylor, the Commission's president, as wanting to "civilize" Native Americans very strongly. Prucha said the Commission's January 1868 report was full of strong feelings about changing Native American ways. He noted that the treaties themselves clearly pushed for "civilization."

The treaties offered land for those who wanted to start farming. They also promised up to $175 worth of "seeds and implements" per family over four years. The government also agreed to provide farmers and other skilled workers. The treaties of Bridger, Laramie, and Medicine Lodge offered yearly prizes of $500 for the 10 families who grew the best crops. The Laramie treaty also added "one good American cow, and one good well-broken pair of American oxen" for each family that moved to a reservation and started farming.

However, much of the land set aside on reservations was not good for farming. Some traditional tribal members refused to farm, even with equipment. Some even threatened the farming instructors. Many were simply unwilling to change their way of life to match the "good life of English education and neat farms."

Funding Issues

One of the biggest problems was that Congress only paid for the talks themselves. They did not set aside money or rules for the promises made in the treaties. These promises included various payments, supplies, building construction, and yearly cash payments to individuals. In May 1868, General Sherman asked Congress for $2 million to cover treaty costs. He was given only $500,000.

Disagreements within the government over this spending largely undid the Commission's work. In 1869, the proposed budget for Native American affairs greatly increased after treaty funding was added. Money bills must start in the House of Representatives, but only the Senate can approve treaties. The two parts of Congress argued and failed to pass the funding bill for several years. According to historian Jill St. Germain, Congress created the Commission but didn't have to support its actions later.

Understanding the Treaties

Many historians have questioned how much the tribes truly understood what they were signing. Talks had to be done through translators, sometimes even through multiple translations. At Bosque Redondo, translators went from English to Spanish to Navajo. This made it hard to express complex ideas clearly.

Historian John Gray said the Fort Laramie treaty was full of "gross contradictions." He believed it was "inconceivable that any Indian was truthfully informed of all its provisions." Anthropologist Raymond DeMallie noted that both sides often gave prepared speeches. Specific questions from Native Americans were rarely answered right away. Many questions were ignored.

According to historian Carolyn Ives Gilman, the Commission thought Native American tribes had a system of power that didn't actually exist. Chiefs were seen as mediators and advisors. They could represent the tribe to outsiders, but they couldn't order others to obey them.

Aftermath and Legacy

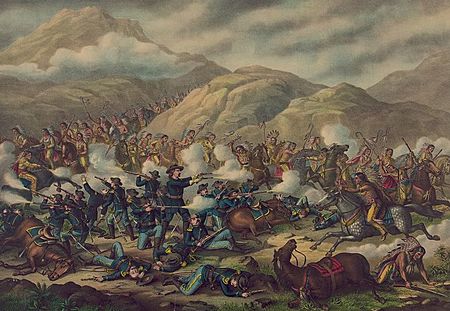

When the Commission ended, it was widely seen as a failure. Violence had already returned to the Southern Plains after the Medicine Lodge agreements broke down. The next month, George Armstrong Custer fought the Cheyenne at the Battle of Washita River. By 1876, Custer would fight his final battle when open war broke out again with the Sioux. This happened despite the Fort Laramie agreement that all sides would stop fighting forever. The second Treaty of Fort Laramie was changed three times by Congress between 1876 and 1889. Each time, more of the 33 million acres of land granted by the treaty was taken. This included taking the Black Hills in 1877 without permission.

The Medicine Lodge Treaty was approved by Congress in 1868. However, the tribes themselves never officially approved it. Within a year, Congress held back promised government payments. General Sherman also worked to limit hunting rights. A decade later, a mistake in the Fort Bridger Treaty helped start the Bannock War.

After the talks at Bosque Redondo, the Navajo became unique. They were the only people to use a treaty to return to their homeland. This was a rare case of Native Americans returning to their original lands. They stayed there and even expanded their land. It became the largest reservation in the nation. From that point on, the Navajo never again fought against white settlers, even though they had many reasons to.

The Senate was slow to act on many treaties. They rejected some, and presidents withdrew others before the Senate could approve them. For the treaties that were approved, like the one at Bosque Redondo, promised benefits from the government were not given. Some promises were not fulfilled even into modern times. When promises were kept, the government did so only after much debate and delay. For example, at Fort Laramie, William S. Harney bought and provided supplies for the Sioux to last through the winter. He then had to explain his "unauthorized expenditures" to Congress.

Some Native Americans returned to raiding both white settlers and other tribes. This was because their families were hungry without the promised government food. At the same time, their traditional ways of life were being destroyed. The government also failed to keep white settlers off the reservations, as agreed. This combination made the public angry. They saw a policy that seemed to feed Native Americans who then went out and killed white people. The main goal of government policy became war against all Native Americans who were not on reservations.

End of Treaties

In 1871, the United States House of Representatives added a rule to the Indian Appropriations Act. This rule ended the practice of making treaties with tribes. It also said that Native American people were now individuals under the care of the federal government.

Congress's efforts to make Medicine Lodge reservations smaller eventually led to the case of Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock. In 1903, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that Congress had the right to break or rewrite treaties with Native American tribes as they saw fit. According to Prucha, by the early 1900s, it was clear that treaty promises, once considered sacred, no longer had to be followed. The treaty system had completely fallen apart.

As historian Robert Oman summarized, the Commission did make some agreements. Their treaty at Fort Laramie effectively ended Red Cloud's War. They also had a big impact on federal policy toward Native Americans. "Yet, despite these accomplishments... instead of initiating an era of peace, the commission commenced a decade of war and bloodshed throughout the Plains."

See also

- American Indian Wars

- English-only movement

- Indian removal

- List of United States treaties

- Numbered Treaties

- Outline of United States federal Indian law and policy

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |