Cherokee Commission facts for kids

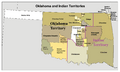

The Cherokee Commission was a special group of three people. President Benjamin Harrison created it to work with Native American tribes. Their main goal was to buy land from the Cherokee Nation and other tribes in what is now Oklahoma Territory. This land was then opened up for non-Native American settlers.

The Commission signed eleven agreements with nineteen tribes between May 1890 and November 1892. Many tribes didn't want to give up their land. Some didn't fully understand the agreements. The Commission even tried to stop tribes from hiring lawyers. Not all the people who translated for the tribes could read or write.

The Commission worked until August 1893. After it ended, there were many lawsuits and investigations. Some tribes, like the Tonkawa, protested the agreements. The Indian Rights Association also criticized how the Commission dealt with the Cheyenne and Arapaho. The Commission tried to make deals with the Osage, Kaw, Otoe, and Ponca tribes, but they didn't succeed.

The Dawes Act of 1887 was an important law. It allowed the U.S. President to divide tribal lands into smaller pieces for individual tribal members. These individual land pieces were held in trust by the government for 25 years, meaning they couldn't be taxed during that time.

Contents

- Understanding the Indian Appropriations Act

- How the Commission Was Organized

- Agreements with Native American Tribes

- Iowa Tribe's Agreement (May 20, 1890)

- Sac and Fox Agreement (June 12, 1890)

- Citizen Band of Potawatomi Agreement (June 25, 1890)

- Absentee Shawnee Agreement (June 26, 1890)

- Cheyenne and Arapaho Agreement (October 1890)

- Wichita and Affiliated Bands Agreement (June 4, 1891)

- Kickapoo Agreement (September 9, 1891)

- Tonkawa Agreement (October 21, 1891)

- Cherokee Agreement (December 1891)

- Comanche, Kiowa and Apache Agreement (October 6–21, 1892)

- Pawnee Agreement (November 23, 1892)

- Failure to Negotiate Treaties

- Images for kids

Understanding the Indian Appropriations Act

On March 2, 1889, President Grover Cleveland signed the Indian Appropriations Act. This law allowed the President to create a three-person group to talk with the Cherokee and other tribes. Their job was to get tribes to give up their lands to the United States. Two days later, Benjamin Harrison became President. This group was officially called the Cherokee Commission. It worked until August 1893. Another part of the Act allowed the President to open land for new settlers. On May 2, 1890, President Harrison signed the Oklahoma Organic Act, which created the Oklahoma Territory.

The Commission received its first money on July 1, 1889. The commissioners were paid for their food, travel, and lodging. They also got extra money for each day they worked. Congress gave the Commission more money several times to continue its work.

How the Commission Was Organized

The Cherokee Commission reported to the Secretary of the Interior, first John Willock Noble and later Michael Hoke Smith. Secretary Noble told the Commission to offer about $1.25 for each acre of land. He also said they could change the price if needed.

Lucius Fairchild from Wisconsin was the first Chairman. He quit after the Commission's first attempt to negotiate with the Cherokee failed. Angus Cameron, also from Wisconsin, took over but resigned after only three weeks. Then, David H. Jerome from Michigan became the Chairman. The only Democrat on the Commission was Judge Alfred M. Wilson from Arkansas. John F. Hartranft, a former Governor of Pennsylvania, was the third member. When Hartranft died in October 1889, President Harrison chose his friend Warren G. Sayre from Indiana to replace him.

Agreements with Native American Tribes

The Cherokee Commission made many agreements with different tribes. These agreements often involved tribes giving up large parts of their land. In return, tribal members would receive smaller, individual plots of land. They also received money from the government.

Iowa Tribe's Agreement (May 20, 1890)

The Iowa tribe originally lived in Wisconsin. They moved several times to avoid white settlers. In 1878, some Iowa people moved to Indian Territory. In 1890, there were about 102 Iowa people on their reservation. They had about 225,000 acres of land. Some Iowa people spoke English and wore "citizens' clothes."

The Commission first tried to talk with the Iowa in October 1889, but the tribe refused. In May 1890, David H. Jerome and the Commission returned. Jerome told the Iowa that the President wanted to offer them individual land plots and buy their extra land. Chief William Tohee wanted the Iowa to keep all their land for future generations. Jerome warned that if they didn't agree, the government would use the Dawes Act to divide their land anyway.

On May 20, 1890, the Iowa tribe signed an agreement. They gave up all their land for $60,000. This was less than 27 cents per acre. The money was paid over 25 years. Each person received 80 acres of land. This land was held in trust by the government for 25 years, meaning it couldn't be taxed. Congress approved this agreement in February 1891. Later, in 1929, a court ruled that the tribe had been underpaid. They were given an additional $254,632.59.

Sac and Fox Agreement (June 12, 1890)

The Sac and Fox Nation in Oklahoma moved to Indian Territory after a treaty in 1867. In 1890, about 515 Sac and Fox people lived on their reservation. They had about 479,667 acres of land. They used the land for grazing, farming, and orchards. Many lived in tipis or bark houses.

The Commission met with the Sac and Fox in October 1889. They offered the tribe land for individual plots and $1.25 per acre for the extra land. When David Jerome became Chairman, the Commission returned in May 1890. Chief Maskosatoe was there, but Moses Keokuk led the talks through an interpreter. Keokuk asked about the land plots and how much land the Commission wanted. Jerome explained the Dawes Act, which gave different amounts of land based on age. Keokuk asked for 200 acres per person and $2.00 per acre for the land they gave up. Jerome didn't agree.

The Sac and Fox National Council insisted on 160 acres per person, no matter their age or marital status. The Commission agreed, but only half of this land would be held in trust for 25 years. The other half would be held in trust for only 5 years, allowing tribal members to sell it sooner.

On June 12, 1890, the tribe signed the agreement. They gave up their land for $485,000, which was a little over $1 per acre. Part of the money went into the U.S. Treasury, some to the local Indian agent, and the rest was paid to tribal members. Congress approved the agreement in February 1891. In 1964, a court ruled the tribe had been underpaid and awarded them an additional $692,564.14.

Citizen Band of Potawatomi Agreement (June 25, 1890)

The Citizen Band of Potawatomi got their name because a treaty in 1887 promised them full citizenship if they moved to a reservation. In 1872, Congress allowed their reservation to be in Indian Territory. In 1890, about 480 Potawatomi people lived on their reservation. They had about 575,000 acres. Many had some white ancestry and spoke English. They were considered a wealthy group.

On June 25, 1890, the tribe signed an agreement. They gave up 575,870.42 acres for $160,000, which was less than 28 cents per acre. Many Potawatomi had already received their individual land plots under the Dawes Act. These land plots were held in trust for 25 years and were tax-free. The total number of land plots was limited to 1,400. If more plots were needed, $1 per acre would be taken from the $160,000 payment. Congress approved the agreement in March 1891. In 1968, the Indian Claims Commission ruled that the land was actually worth $3 an acre. They awarded the Potawatomi an additional $797,508.99.

Absentee Shawnee Agreement (June 26, 1890)

The Absentee-Shawnee were named this because they were not on the Shawnee reservation in Kansas. They lived on the Oklahoma Potawatomi reservation. In 1890, about 640 Absentee-Shawnee people lived there. They had advanced to wearing "civilized clothing," lived in log houses, and owned livestock. The group was split into two bands: the Lower Shawnee led by Chief White Turkey and the Upper Shawnee led by Big Jim.

On June 26, 1890, the Absentee-Shawnee signed an agreement. They gave up 578,870.42 acres for $65,000, which was less than 11 cents an acre. Big Jim of the Upper Shawnee refused to sign. The Shawnee received individual land plots under the Dawes Act, limited to 650 plots. If more plots were made, $1 per acre would be taken from the $65,000 payment. These land plots were held in trust for 25 years and were tax-free. Congress approved the agreement in March 1891. In 1999, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that only the Potawatomi had rights to the land given up in 1890. So, the Absentee-Shawnee could not share in the 1968 payment.

Cheyenne and Arapaho Agreement (October 1890)

The Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes had their land boundaries set by treaties in 1851 and 1861. The 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty assigned them a reservation in the Cherokee Outlet. This treaty also said that three-fourths of all adult males in the tribe had to sign any land cession agreement. In 1890, there were 2,272 Cheyenne and 1,100 Arapaho people.

The Ghost Dance religion became popular among the Arapaho at this time. It was started by a Northern Paiute prophet named Wovoka. People believed he would bring back the buffalo and remove white people from tribal lands. Some Cheyenne leaders, like Porcupine, became strong believers. This led some tribal members to focus on dancing instead of their work.

On July 5, 1890, the Commission met with Cheyenne leaders who were against giving up land. The Commission was told to get signatures from three-fourths of the adult males, as required by the 1867 treaty. On July 7, the Commission started talks by mentioning the 1887 Dawes Act, which allowed the President to divide land. The tribes refused, saying their land was given to them by the Great Spirit and by the treaty. On July 9, the Commission said the tribes "will be the richest people on earth." The crowd was not convinced. On July 14, Jerome threatened to stop giving them food rations. The Cheyenne began to boycott the meetings.

The Commission and Secretary Noble met to discuss their next steps. They wanted to change the Dawes Act to set a time limit for tribes to accept land divisions. They also wanted to stop outside cattle from grazing on tribal land. On October 7, the Cheyenne boycotted the talks again, and the Arapaho refused to continue.

The Commission started collecting signatures on October 13. By November 12, Secretary Noble said they had enough signatures for the agreement. However, tribal members complained of fraud. They said women and underage males were counted as signers. They also claimed the Commission combined the signatures from both tribes instead of counting them separately.

Under the agreement signed in October 1890, the tribes were to receive $1,500,000. Two payments of $250,000 each were made, and the remaining $1,000,000 was held by the U.S. Treasury, earning 5% interest. Each person was to receive 160 acres of land. This land was held in trust for 25 years and was tax-free. Congress approved the agreement in March 1891.

Tribal Lawyers and Claims

The Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes hired lawyers to represent them. These lawyers' fees were taken from the money paid to the tribes. The tribes complained about these fees. People like Charles Painter of the Indian Rights Association investigated. Painter said the Commission used "trickery, coercion, threats and cunning." He also claimed the lawyers caused the tribes to lose three-fourths of their land's value. Congress did not act on these complaints.

In 1951, the tribes sued the United States. The Indian Claims Commission found that the 51,210,000 acres of land were worth $23,500,000 at the time of the agreement. The tribes settled with the government for $15,000,000.

Wichita and Affiliated Bands Agreement (June 4, 1891)

In 1855, a treaty allowed the U.S. to lease land for the Wichita and other tribes. This area was called the Leased District. After the Civil War, the U.S. bought this district. Other tribes, like the Kiowa, Comanche, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, also received reservations there. Because the Wichita felt crowded, the government tried to increase their reservation in 1872. However, Congress never approved this.

In 1890, the Wichita reservation had 991 people, divided into six bands: Wichita, Caddo, Tawakoni, Kichai, Delaware, and Waco.

The Commission began talks with the Wichita on May 9, 1891. They explained the Dawes Act and asked the Wichita to give up land. Tawakoni Jim immediately asked for a lawyer to represent the tribes. Jerome tried to say it was a waste of money. Caddo Jake said educating children should come before any talks. Tribal members expressed their distrust of the government because of broken treaty promises.

The Commission offered 160 acres per person and $286,000 for the extra land. When asked, Sayre said they were offering only 50 cents per acre. When it was clear the Wichita wouldn't negotiate without a lawyer, the government provided Luther H. Pike. Pike and the Wichita agreed to the Commission's terms, except for the price per acre. Jerome agreed to let Congress decide the price.

On June 4, 1891, the Wichita signed an agreement to give up their extra land. Congress would set the price. Each person received 160 acres of land. The total number of land plots was limited to 1,060. These land plots were held in trust for 25 years and were tax-free. Congress approved the agreement in March 1895.

In 1899, a court ruled that only the Choctaw and Chickasaw tribes should get the payment for the extra land. The Wichita appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, which overturned the ruling. The court then awarded the Wichitas $673,371.91 ($1.25 an acre) for their land. When Congress finally paid in 1902, they took out money for lawyer fees.

Kickapoo Agreement (September 9, 1891)

The Kickapoo were a nomadic tribe. By the 1800s, they were split between Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. Some moved to Mexico. In 1873, some Kickapoo were forced to move to Indian Territory. In 1890, there were about 325 Kickapoo people on their reservation. They had about 200,000 acres. They were known as good farmers.

The Commission first met the Kickapoo in October 1889, but the tribe wasn't interested in individual land plots. In June 1890, the Commission returned, but the Kickapoo again refused. In June 1891, the Commission tried again. The Kickapoo said they didn't want to anger the Great Spirit by giving up their land.

Jerome moved the talks to Washington, D.C.. Kickapoo leaders were authorized to represent the tribe. On September 9, 1891, in Washington, D.C., the Kickapoo signed an agreement. They gave up their lands for $64,650, which was about 32 cents per acre. Each person received 80 acres of land, with a limit of 300 plots. These land plots were held in trust for 25 years and were tax-free. The interpreter for the Kickapoo said he could not read or write. Congress approved the agreement in March 1893.

In 1894, a Quaker worker reported that most Kickapoo didn't understand they were giving up their land. With help from the Indian Rights Association, the Kickapoo presented their case to Congress. They claimed the Commission used "trickery, coercion, threats and cunning." In 1908, Congress gave the tribe another $215,000, but again deducted money for lawyer services.

Tonkawa Agreement (October 21, 1891)

The Tonkawa tribe, originally from Texas, almost disappeared as buffalo herds dwindled. In 1859, the U.S. government moved them to Indian Territory. During the Civil War, a difficult event greatly reduced their numbers. In 1885, the Tonkawa moved to the Cherokee Outlet and served as scouts for the U.S. Army. In 1890, there were about 76 Tonkawa people. Many dressed in white society's clothes and tried to speak only English. They were described as "ready and anxious" to accept individual land plots.

On October 21, 1891, the Tonkawa signed an agreement. They gave up their entire 90,710.89 acres for $30,600, which was about 34 cents per acre. Part of the money was paid in cash, and the rest was held in trust by the U.S. Treasury, earning 5% interest. Sixty-nine land plots were agreed upon. These land plots were held in trust for 25 years and were tax-free. Congress approved the agreement in February 1893.

The Tonkawa later hired lawyers. They claimed they were pressured into signing the agreement. They said they were threatened that their land plots would be canceled if they didn't agree. They also claimed they had asked for $1.25 per acre. Congress did not act on their claim.

Cherokee Agreement (December 1891)

Between 1836 and 1839, the Cherokee removal forced the tribe from their lands. The 1835 Treaty of New Echota created their reservation in Oklahoma, including the "Cherokee Outlet." This land was also known as the Cherokee Strip. When cattle ranchers started leasing grazing land on the Outlet, the Cherokees taxed them. Some ranchers ignored the taxes and built fences. In 1883, the government forced the fences to be removed.

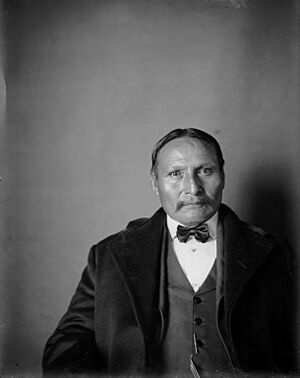

Joel B. Mayes was the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. He was a former teacher and farmer. He was in charge of renegotiating the grazing leases on the Outlet. He was re-elected Chief in 1891 and died that December. Colonel Johnson Harris then became chief.

In July 1889, Secretary Noble told the Commission to start talks with the Cherokees to buy the Outlet. Most Cherokees didn't want to sell the land. Chief Mayes wanted to increase tribal income by raising taxes on cattle ranchers. The Commission arrived in Tahlequah in July 1889 and made an offer in August. The Cherokees didn't agree. In December 1889, the Commission's offer was withdrawn. President Harrison then banned all cattle from the Outlet, which stopped the Cherokee's income from it.

In November 1890, the Commission, with Jerome as Chairman, returned to talks. Chief Mayes appointed a nine-member committee to negotiate. By December 26, 1890, the talks failed again.

In February 1891, the United States House Committee on Territories suggested skipping talks and just taking the Outlet. They recommended paying the Cherokees $1.25 an acre. Judges in Oklahoma Territory also ruled that the Cherokees didn't legally own the Outlet. The Cherokees showed documents proving their ownership.

The Commission reopened talks with the Cherokees in November 1891. The Cherokees asked for the Outlet's boundary to be moved and for the government to estimate the land's size. A big problem was the issue of "intruders"—outside workers living on Cherokee land—and the U.S. government's failure to handle this. The Cherokee Nation asked for $3 an acre. Jerome and Sayre made fun of this offer. The Commission threatened that Congress could remove the tribe from certain laws. On December 11, they almost reached an agreement, with the Cherokees asking for $2 an acre.

On December 19, a compromise was reached. The Agreement with the Cherokee (1891) was approved by the Cherokee National Council on January 4, 1892. The Cherokees gave up 8,144,682.91 acres for $8,595,736.12. Congress approved the agreement in March 1893. In 1961, the Indian Claims Commission awarded the Cherokee Nation an additional $14,364,476.15. They ruled the land was actually worth $3.75 an acre in 1892.

Comanche, Kiowa and Apache Agreement (October 6–21, 1892)

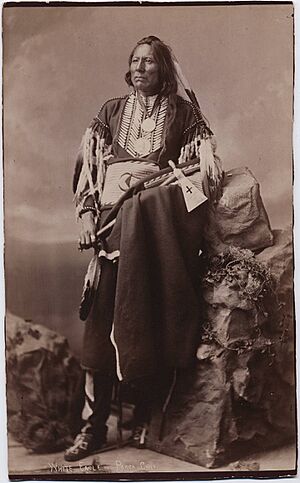

On October 21, 1867, the Kiowa and Comanche tribes signed the Medicine Lodge Treaty. This treaty moved them to a shared reservation in Indian Territory. It also said that three-fourths of all adult males had to sign any land cession. Not all tribal members moved to the reservation right away. Quanah Parker, a Comanche leader, later became wealthy by leasing cattle land. He was paid by cattlemen and represented them in Washington D.C. In 1892, there were 1,014 Kiowa, 1,531 Comanche, and 241 Apache people on the reservation.

The Commission began talks with the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache at Fort Sill on September 26, 1892. Quanah Parker immediately asked how much money per acre and what the terms were. Jerome avoided giving details about the money. Other tribal members wanted to wait until the Medicine Lodge Treaty expired. Parker kept asking for financial details, but Jerome avoided them. Sayre explained the offer of $2,000,000 to be divided among them. Parker asked how Sayre came up with that number, and Sayre replied, "...we just guess at it." Parker noted that prices per acre varied for different tribes.

On October 3, Wilson reminded the tribes about the 1887 Dawes Act, saying the government could force land division. Parker suggested one representative from each tribe meet with a lawyer to prepare a tribal proposal. The Indian agent told the tribes they could accept the Commission's offer or be forced into land division by the Dawes Act. Jerome wrongly used Parker's wealth as an example of what land division would bring to others. Parker suggested adding $500,000 to the $2,000,000 offer. Kiowa chief Tohauson said he and many in his tribe would not sign.

The Commission continued to press for signatures. On October 22, the Commission told the President they had enough signatures for the agreement.

Protests immediately started. People claimed there were problems getting signatures and that individuals were misled about the terms. Lone Wolf and Quanah Parker went to Washington D.C. many times to share their views. From 1893 until 1900, Congress tried to change the agreement before finally approving it.

Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock

After the Commission claimed enough signatures, Lone Wolf and other Kiowa leaders said there was fraud. In October 1899, a petition from most Kiowa males questioned the agreement's validity. When the land division process began, Lone Wolf filed a complaint with the Supreme Court. He argued the agreement was against the Constitution because it didn't meet the treaty's requirement of three-fourths of adult male signatures.

In the 1903 case of Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, the Court ruled against Lone Wolf. The Court said that Congress acted in good faith and that the courts should not question Congress's reasons. The Court ruled that Congress had the power to change treaties if it believed it was in the best interest of the tribes.

Pawnee Agreement (November 23, 1892)

The Pawnee tribe had four main groups. In 1876, the Pawnee gave up their reservation in Nebraska. The U.S. government sold this land and used the money to move the tribe to Indian Territory, on land bought from the Cherokee. The Pawnee owned about 230,014 acres in the Outlet and 53,006 acres south of there.

In 1892, there were about 798 Pawnee people. About 400 were of mixed heritage. Many could speak English. The report also mentioned the Pawnee's involvement in the Ghost Dance. This spiritual movement promised a new leader who would remove outsiders and bring back the buffalo. The government tried to stop the Ghost Dance by arresting a leader named Frank White.

The Commission met with the Pawnee on October 31, 1892. Jerome told the Pawnee they had no choice but to agree. He said leasing land to cattle ranchers was forbidden. The Pawnee worried about losing their way of life and about future generations. Jerome threatened to cut off their food rations. He told them that giving their land to the government was their only protection from white settlers.

On November 2, Jerome presented the government's offer. The Pawnee didn't like the $1.25 per acre price. They also didn't like that only 80 acres of their 160-acre plots could be used for farming. The Pawnee wanted all 160 acres without restrictions and $2.50 per acre for the land they gave up. Sun Chief had heard that Quanah Parker got $1.50 per acre, but Jerome said the Comanches only got 80 cents. After several days, the Pawnee lowered their price to $1.50 an acre, but Jerome refused. Sun Chief offered to meet in the middle, but Jerome still refused.

Sun Chief finally approved the Commission's agreement. On November 23, the Agreement with the Pawnee (1892) was signed. From their 283,020-acre reservation, 111,932 acres became individual land plots. The remaining 171,088 acres were given up as extra land for $1.25 per acre. $80,000 was paid in cash, and the rest was held in the U.S. Treasury, earning 5% interest. The individual land plots were held in trust for 25 years and were tax-free. Congress approved the agreement in March 1893. In 1950, the Indian Claims Commission ruled the Pawnee had been underpaid for their Nebraska reservation and awarded them over $7,000,000.

Failure to Negotiate Treaties

The Cherokee Commission tried to make agreements with several other tribes but was not successful.

Osage, Kaw and Otoe Tribes

In 1892, the Osage reservation had 1,644 people. The Osage were described as religious and proud of their heritage. The Kaw on the reservation numbered 209. They were described as generous. In June 1893, the Commission tried to talk with the Osage and Kaw. Neither tribe was interested. The Dawes Act did not apply to the Osage, so they couldn't be forced to accept individual land plots. The Osage had their own government. The Kaw refused to consider land plots unless the Commission could make a deal with the Ponca.

In 1892, the Otoe tribe had 362 people living on 129,113 acres. The Ghost Dance, which the agent called "The Messiah Craze," was stopped by arresting a participant. The Otoe refused to meet with the Commission.

Ponca Tribe

In 1868, the Ponca land in Dakota Territory was given to the Sioux. In 1877, the Ponca were forced to move to Indian Territory. President Rutherford B. Hayes denied their appeal to stop the move. The Ponca lived on 101,894 acres in the Outlet, which they bought for $50,000 in 1878. In 1892, there were 567 Ponca people. Many could speak English.

The Commission met with the Ponca in October 1891 and spring 1892. The commissioners read the Dawes Act. White Eagle suggested white settlers "...stay on their own reservation." The Ponca felt that individual land plots didn't make a difference in a tribe's living standards. The Commission threatened that Congress could cut off the Ponca's yearly money. The Ponca visited the Cherokee Nation for advice, but the Cherokee couldn't help.

In April 1893, talks restarted. Jerome threatened that the government could do anything it wanted. He told the Ponca that the Commission would stay until the Ponca agreed to individual land plots. Sayre threatened to cancel money from grass leases. The Ponca stood firm, saying they owned the land. They reminded the Commission of what happened to their land in Dakota Territory. Jerome responded that the government would force the land division and even threatened one person with jail. The Commission threatened to cut off all government services. The Commission finally gave up on June 6, 1893, after 20 months of trying.

Images for kids

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |