Porcupine (Cheyenne) facts for kids

Porcupine (born around 1848, died 1929) was an important Cheyenne chief and medicine man. He is most famous for introducing the Ghost Dance religion to his people. Porcupine grew up with the Sioux tribe because his mother was Sioux. He later married a Cheyenne woman and became a brave warrior in the Cheyenne's special group called the Dog Soldiers.

Porcupine fought against the U.S. Army in a conflict known as Hancock's War in 1867. During this time, the Cheyenne people did not want to move to a reservation. Porcupine's group was chased by the 7th Cavalry from Kansas to Nebraska. In Nebraska, he managed to make a train go off its tracks, which was the first time Native Americans had done this. After the Great Sioux War of 1876, the Cheyenne surrendered and were sent to Oklahoma. Porcupine was part of the Northern Cheyenne Exodus. This was when some of the starving tribe fought their way back to their homeland in Montana.

In 1889, Porcupine traveled all the way to Nevada to meet Wovoka. Wovoka was the prophet of the new Ghost Dance religion. Porcupine believed that Wovoka was a special leader who would help Native Americans. He thought Wovoka would bring back the buffalo and make the white settlers leave the continent. Porcupine returned home to teach the Ghost Dance to the Cheyennes. He began to welcome new followers into his church. The Ghost Dance quickly spread among many plains tribes.

The U.S. Army tried to stop the Ghost Dance. They worried it would cause a new Native American uprising. While the Cheyenne did not suffer as much as the Sioux at Wounded Knee, Porcupine had to perform the dance in secret after 1890. In 1900, he was put in prison for trying to bring the religion back. Like Wovoka, Porcupine taught peace. He never took part in any violence linked to the Ghost Dance. He also served as a chief for the Cheyenne in several treaty meetings with the U.S. government. This included leading a group to Washington D.C.

Contents

Porcupine's Early Life

Porcupine was born around 1848. He grew up with the Sioux people. His father was Sioux, and his mother was Cheyenne. When he grew up, he married a Cheyenne woman. He then became a member of the Cheyenne tribe. This was a common custom: a husband would usually live with his wife's family. Like most young Cheyenne men, Porcupine joined a special warrior group. He became a member of the famous Dog Soldiers.

Hancock's War and Its Impact

After the American Civil War, the U.S. government wanted to move Plains Indians to reservations. General Ulysses S. Grant oversaw several military actions to make this happen. General Winfield Scott Hancock led one of these efforts in West Kansas. His main goal was to move the Southern Cheyenne in the Smoky Hills area.

In April 1867, Hancock brought a large army to Fort Larned. He demanded that Native American leaders meet him there. He hoped to scare them with a show of force. However, Edward W. Wynkoop, the Indian agent for the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho, warned him. Wynkoop said that this would seem like an attack and was not good for peace talks. Hancock did not listen to this advice.

The Native Americans were careful about going to the fort. A camp of Southern Cheyenne and Oglala Sioux was set up about thirty miles away. A few leaders, including Tall Bull of the Dog Soldiers, went to the fort. Hancock threatened them with war if they did not agree to his terms. But they simply returned to their camp. Hancock was angry that many leaders did not meet him. He decided to move his whole army to their camp. The Indian agents warned him again that this would be seen as an attack.

The Native Americans tried to stop Hancock by setting fire to the prairie. But this did not work. Outside the camp, there was a tense meeting with the Cheyenne leader Roman Nose. Hancock spoke harshly to Roman Nose. Roman Nose then told his friend, Bull Bear, to ride away. He planned to kill Hancock in front of his soldiers and did not want Bull Bear to get hurt. Instead, Bull Bear led Roman Nose away.

Hancock then ordered his soldiers to capture the camp. But when they entered, it was empty. The Native Americans had already left and scattered. They feared another event like the Sand Creek massacre. Hancock waited three days. Then he ordered the camp to be burned. Many people, both then and now, felt this action was unnecessary and started a war. Porcupine, who was nineteen years old, was one of the Native Americans being chased by Custer.

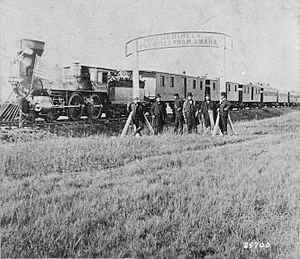

The First Train Attack by Native Americans

Porcupine and his friend, Red Wolf, fled north from Custer's soldiers. They joined a group of Cheyenne led by Turkey Leg and Spotted Wolf. This was near the Union Pacific Railroad in Nebraska. Porcupine had an idea to stop or damage a train.

On August 6, 1867, Porcupine and Red Wolf placed a railroad tie across the tracks. This was three miles west of Plum Creek (now Lexington). They tied it down with wire taken from the telegraph line. At sunset, they lit a fire. Two men, Pat Handerhan and William Thompson, were sent on a handcar to check the broken telegraph line. They were distracted by the fire and hit the obstruction. Porcupine and Red Wolf shot at the men. Handerhan was killed, and Thompson was wounded but pretended to be dead and survived. Porcupine and Red Wolf found two Spencer carbines in the handcar. These were new types of rifles that opened up. They did not understand them, as they only knew older muzzle-loading rifles. Thinking the rifles were broken, they threw them away.

Encouraged by this, the Native Americans decided to do more damage to the tracks. They pulled up the rails, bent them, and built a bigger barrier. Late on the night of August 7, two freight trains approached. Some of the Native Americans came out and chased the first train on horseback. They shot at it and even tried to stop the engine with a lasso. This did not work, but it made the train's engineer, Brooks Bower, speed up to escape. The train hit the damaged tracks at full speed. Bower was thrown from the train and died. The survivors from the wreck went back to the second train. They picked up people from Plum Creek Station and took them to Elm Creek.

In the morning, the first train was completely looted and then burned. Colorful cloth from the train was tied to the tails of the warriors' ponies. They unrolled like flags as the ponies ran. These were taken back to camp for the women. Porcupine's actions that day led to the first train derailment caused by Native Americans.

The Northern Cheyenne Exodus

After the Great Sioux War of 1876, the Cheyenne were forced to move to reservations in Oklahoma. There, they found that the hunting grounds had no large game for them to survive. Also, the supplies promised by the U.S. government often did not arrive or were stolen. Facing starvation, chiefs Dull Knife and Little Wolf led the Northern Cheyenne in 1878. They began a difficult journey back to their homeland in Montana, over a thousand miles away. The U.S. cavalry chased them the whole way. Porcupine was part of this brave journey, known as the Northern Cheyenne Exodus.

Dull Knife's group surrendered at Fort Robinson in Nebraska. They were imprisoned there and denied food and heat, even though it was freezing cold. This was because they refused to go back to Oklahoma. Nearly half of them were killed in a desperate escape from Fort Robinson. Little Wolf surrendered in March 1879 at Fort Keogh in Montana. Little Wolf's group was allowed to stay, and Dull Knife's survivors later joined them.

During the journey north, some Kansas settlers had been killed. There were calls to put the entire Cheyenne group on trial. As a compromise, the military sent seven Native Americans for trial in a civilian court. These included Wild Hog, a war chief, Porcupine, and five others. Items taken from homes in Kansas had been found with the Native Americans. They were sent to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in early 1879 to await trial. From there, they were taken to Dodge City by lawman Bat Masterson for their trial.

This was not an easy trip. Large, sometimes unruly, crowds came out to see the Native Americans. In Lawrence, Masterson had to hit the city marshal to keep order. The trial began in Dodge City on June 24. The defense lawyer successfully argued that local bias would prevent a fair trial. He asked for the trial to be moved to Lawrence, which was granted. The defense planned to show how unfair the reservation system was. They even called important figures like General Nelson A. Miles, General John Pope, and Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz to testify. Meanwhile, the prosecution had trouble getting witnesses to travel to Lawrence. When the chief prosecutor did not show up on October 13, all charges were dropped.

The Ghost Dance and Porcupine's Role

The Ghost Dance religion was started by its prophet Wovoka in Nevada. Wovoka was a Paiute Native American. He had a special vision on January 1, 1889, during a solar eclipse. In this vision, he was taken to heaven. There, he was given a dance, the Ghost Dance, to share with Native Americans. This dance would ensure their place in heaven. Wovoka's religion was much like Christianity. He said that a special leader, like the Christian Jesus, would come to Earth. This leader would bring back all the Native American dead. All white people would leave Earth, and the buffalo would return. Wovoka predicted this would happen in Spring 1891. Until then, Wovoka taught that Native Americans should not fight the whites. Instead, they should perform the Ghost Dance.

In November 1889, Porcupine led a Cheyenne group to visit the Arapahoes in Wyoming. His companions were Grasshopper and a younger man. In Wyoming, Porcupine changed their plan and continued to Nevada to see Wovoka. They stayed there over the winter and returned in the spring of 1890. Porcupine's report to the tribal council of chiefs took five days to share. After hearing him, the council gave him permission to teach Wovoka's message to the tribe. This is how Porcupine became the main teacher of the Ghost Dance among the Cheyennes. Porcupine taught that Wovoka was a special leader, like Christ.

Porcupine said his visit to Wovoka was a lucky side trip from visiting the Arapahoes. He spoke as if only the Cheyenne group went alone. However, James Mooney, a government researcher who studied the Ghost Dance, told a different story. Mooney interviewed many people involved, including Wovoka himself. He said Porcupine's group was part of a larger, planned mission. Perhaps a dozen people were sent by a meeting of chiefs in Wyoming. Their clear purpose was to learn about the new religion. This mission included people from the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Shoshoni tribes. It seems the Arapaho visit was a cover story. It made it easier to get permission from the Indian agent to leave the reservation. U.S. soldiers guarded the reservation and were ordered to stop anyone leaving without a permit. Porcupine, however, traveled without a permit until he reached Fort Hall Indian Reservation in Idaho. There, the Indian agent gave him one. At Fort Hall, more Shoshoni and Bannock Indians joined them. The Indian agent in Nevada reported that the group had thirty-four people when they passed through. Porcupine said that all the Native Americans they met after Fort Hall were already doing the Ghost Dance. He also said that many white people, mostly Mormons in Nevada, were dancing too.

How White Settlers Reacted

The Ghost Dance religion was not just for the Cheyennes. It spread across many plains tribes. White settlers living near reservations became worried. They feared it would lead to a new Native American uprising. They asked the army to step in. Native American dances had been made illegal by the Indian Religious Crimes Code in 1883. This law stayed until 1934.

White fear of the movement led to conflict between the army and the Sioux. This resulted in the killing of the Hunkpapa Sioux chief Sitting Bull and the terrible Wounded Knee Massacre in December 1890. At Porcupine's location on the Northern Cheyenne reservation, more soldiers were sent from Fort Keogh to the Lame Deer agency. The army sent Sgt. Willis Rowland, a scout who was part Cheyenne and part white. His job was to gather information on Porcupine's teachings. Rowland joined Porcupine's church and was welcomed into it. Rowland did not like having to be sneaky. He said, "I hated to do this, but it seemed like it was the best way." After three days, he reported to his commanders. He said that Porcupine's teachings were completely peaceful. He also said that no one was talking about fighting white people.

Even so, the government stopped the Ghost Dance. The Northern Cheyenne sometimes managed to hold illegal Ghost Dances. They would convince soldiers trying to break it up that it was a different dance.

Some time after the Ghost Dance was stopped, Porcupine moved to the Oglala Sioux Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. The Sioux and Cheyennes had always been friends. They had fought together before the Cheyenne surrendered. Porcupine himself was half Sioux. However, after Wounded Knee, Porcupine and sixty others were temporarily moved to the Northern Cheyenne Reservation. Many Cheyenne were army scouts, and it was thought they would not be safe at Pine Ridge. They became stuck in a confusing situation there. Porcupine believed they should have received their share of money. This money came from the forced sale of reservation land in South Dakota to the government in 1889. They did not get it because they were no longer officially listed at Pine Ridge. This was true even though their move was only supposed to be temporary. Some of them were paid after waiting a year.

The Ghost Dance religion became less popular when the special leader and the return of the dead did not happen as predicted. However, it did not completely disappear. A small part of it still exists today. Porcupine tried to bring the religion back in 1900. The Indian agent, James C. Clifford, collected a petition from Northern Cheyennes. This petition asked for Porcupine to be put in prison. Porcupine was arrested in October and given hard labor at Fort Keogh. He was released on February 28, 1901, after promising to behave.

In 1918, there was an attempt to start a revolt on the Northern Cheyenne reservation. This was also inspired by the idea of a special leader. White people at the agency were so scared that they carried guns and stored ammunition. However, the attempt was stopped quickly with strong warnings to the Native Americans. Porcupine did not take part in this, or any other, attempted rebellion linked to the special leader. He remained peaceful throughout this time.

Porcupine as a Political Leader

Porcupine was a chief of the Northern Cheyenne. However, the U.S. government never officially recognized him as such. This was probably because of his connection to the Ghost Dance. He was also a very powerful medicine man. According to historian Thomas B. Marquis, Porcupine had more influence than even the highest-ranking medicine man in the tribe.

He was involved in four different treaty meetings with the U.S. government. These meetings led to official treaties. Porcupine believed that the U.S. had broken all of these agreements. He was most upset when the U.S. broke the treaty about the Black Hills. This happened after gold was found there. This broken treaty was the main reason for the 1876 war. Porcupine was the spokesman for a Cheyenne group that visited Washington D.C. This happened during the presidency of Benjamin Harrison (1889–1893). The purpose of their visit was to ask for payment for the broken treaties.

Porcupine's Character

When Porcupine was teaching the Ghost Dance, he was a man of peace. This was different from his younger days as a warrior. Historian Thomas B. Marquis met Porcupine and wrote about him. Marquis said, "As a 'bad Indian' he was of the most gentle type. The high regard for him was not restricted to his own people ... Even the missionaries liked him, their only condemnation being that he was an apostle of paganism."

Porcupine had two sons. Both of them died from tuberculosis. This was a common disease among the Cheyenne during the reservation period. They had little natural protection against it. Porcupine passed away in 1929.

|

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |