Indian removals in Indiana facts for kids

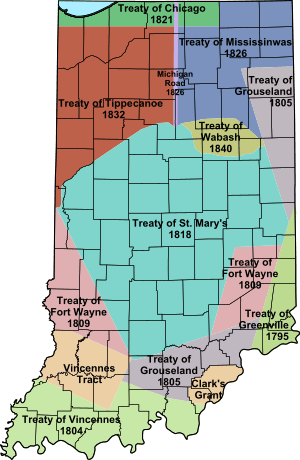

The removal of Native Americans in Indiana was a series of events where most native tribes were moved from their lands in Indiana. This happened because of many land agreements, called treaties, signed between 1795 and 1846. While some removals happened before 1830, most took place from 1830 to 1846.

Tribes like the Lenape (Delaware), Piankashaw, Kickapoo, Wea, and Shawnee were moved in the 1820s and 1830s. The Potawatomi and Miami removals happened later, between the 1830s and 1840s. These were more gradual, and not all Native Americans left Indiana willingly. A famous example of forced removal was the Potawatomi Trail of Death in 1838. During this event, Chief Menominee and his Potawatomi band were forced to march to Kansas. Out of 859 Potawatomi, at least forty people died on this difficult journey.

The Miami were the last major tribe to be moved from Indiana. Their leaders managed to delay the process until 1846. Many Miami people were allowed to stay on their land. This was thanks to special land allotments given to them in treaties, like the Treaty of St. Mary's (1818).

Between 1803 and 1809, William Henry Harrison, who later became a U.S. President, made many treaties. He bought almost all the Native American land in what is now Illinois and southern Indiana for the U.S. government. Most of the Wea and Kickapoo tribes moved west to Illinois and Missouri after 1813. The Treaty of St. Mary's led to the Delaware tribe moving in 1820. The remaining Kickapoo also moved west of the Mississippi River.

After the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, removals in Indiana became part of a bigger plan across the country. This plan was carried out under President Andrew Jackson. By then, most tribes had already left Indiana. The main tribes left were the Miami and Potawatomi. They were already living on smaller reservation lands because of earlier treaties. Between 1832 and 1837, the Potawatomi gave up their Indiana land. They agreed to move to reservations in Kansas. A small group of Potawatomi also joined their people in Canada.

Between 1834 and 1846, the Miami gave up their reservation land in Indiana. They agreed to move west of the Mississippi River. The biggest Miami removal to Kansas happened in October 1846.

Not all Native Americans left Indiana. Less than half of the Miami tribe moved. More than half either came back to Indiana or were never required to leave. The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians were the only other Native Americans left in the state after the main removals ended. Those who stayed settled on private land. They slowly became part of the larger culture, but some kept their Native American heritage. Members of the Miami Nation of Indiana mostly live along the Wabash River. Other Native Americans settled in cities like Indianapolis and Fort Wayne. In 2000, over 39,000 Native Americans from more than 150 tribes lived in Indiana.

Contents

Native American Settlements in Indiana

The Miami people and the Potawatomi were the most important native tribes in the area now called Indiana. In the late 1600s and early 1700s, some of these Algonquian groups returned from the north. They had gone there to escape conflicts with the Iroquois during the Beaver Wars.

The Miami remained Indiana's largest tribal group. They lived along the Maumee, Wabash, and Miami rivers in central and west-central Indiana. Their main settlement was Kekionga, near where Fort Wayne, Indiana is today. They also owned land in a large part of northwest Ohio. The Potawatomi settled north of the Wabash River, near Lake Michigan in northern Indiana, and in present-day Michigan.

The Wea lived on the middle Wabash River, near today's Lafayette. The Piankeshaw settled near the French town of Vincennes, Indiana. The Eel River band lived along the Eel River in northwestern and north-central Indiana. The Shawnee came to west-central Indiana after American colonists forced them out of Ohio. Smaller groups, like the Lenape (Delaware), Wyandott, and Kickapoo, lived in other areas. These tribes lived in farming villages along rivers. They traded furs for European goods with French traders, who arrived in the late 1600s.

Understanding the Treaties

Early Land Agreements

After Britain won the French and Indian War (part of the Seven Years' War), the Treaty of Paris (1763) gave Britain control over North American lands east of the Mississippi River. Many American settlers then moved west. Native American tribes were unhappy with British policies and started Pontiac's War. In response, the British government issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This rule tried to stop American colonists from settling west of the Appalachian Mountains, but it didn't work well. Settlers kept moving onto Native American lands.

After the American Revolutionary War, Britain and the new United States signed the Treaty of Paris (1783). Britain gave the Americans a large part of its land claims, including what is now Indiana. However, the native tribes who lived on the land said they were not part of the treaty talks. They ignored its rules. More talks were held to decide how much the tribes would be paid for their lands. American soldiers were also sent to control Native American resistance.

A group of Native American tribes fought against the Americans in the Northwest Indian War. The tribes were defeated at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. After this, the British left the Northwest Territory, and the tribes lost their military support. This defeat was a major turning point. It led to tribes giving up their lands and most Native Americans eventually being removed from what is now Indiana.

The Treaty of Greenville in 1795 was the first treaty to take Native American land in what became Indiana. It made it easier for American settlers to reach lands north of the Ohio River. Under this treaty, the American government gained two-thirds of present-day Ohio. They also got a small piece of land in southeastern Indiana, the Wabash-Maumee portage (near Fort Wayne, Indiana), and early settlements at Vincennes, Indiana, Ouiatenon, and Clark's Grant (near Clarksville, Indiana). In return, the Native Americans received goods worth $20,000 and yearly payments. Most of the remaining territory, including a large part of Indiana, was still occupied by native tribes. However, tribes living along the Wabash-Maumee portage had to move. The Shawnee moved east to Ohio. The Delaware settled villages along the White River. The Miami at Kekionga moved to the Upper Wabash River.

Treaties During Indiana's Early Years

Native American removal followed a series of land treaties that started when Indiana was a territory. The Northwest Ordinance (1787) created the Northwest Territory. It planned for this land to be divided into smaller territories, including the Indiana Territory, which was set up in 1800.

One of the first goals for the U.S. government and William Henry Harrison was to encourage quick settlement. Harrison was appointed governor of the Indiana Territory in 1800 and served until 1812. He needed to reduce threats from native tribes and create a plan for gaining ownership of territorial lands. At first, Harrison could not make treaties. But after 1803, President Thomas Jefferson gave him the power to negotiate with tribes. This was to open up new land for settlement, especially the Vincennes tract. This land had been bought by French authorities from the natives in the mid-1700s. It was then given to Britain after the French and Indian War, and finally to the Americans after the Revolutionary War.

Harrison wanted to expand settlements beyond Vincennes and Clarks Grant through land treaties. Efforts were also made to encourage Native Americans to become farmers. The other option was to move them to unsettled lands farther west. Harrison's methods to get land from the Native Americans included tough talks with weaker tribes first. Then, he would divide and conquer the remaining groups. The American military was ready to help if there were conflicts.

Harrison offered yearly payments of money and goods for land. He also rewarded tribal leaders who cooperated with trips to Washington, D.C. and offered bribes. Talks often used people who could translate, like Jean Baptiste Richardville, William Wells, and William Conner.

Between 1803 and 1809, Harrison negotiated land treaties with the Delaware, Shawnee, Potawatomi, and Miami tribes, among others. He gained almost all the Native American land in most of present-day Illinois and the southern third of Indiana. In total, Harrison negotiated thirteen land treaties across the Northwest Territory. This included eleven land treaties from 1803 to 1809 that covered over 2.5 million acres (10,000 km²) in the Indiana Territory. Several things helped Harrison: the fur trade was declining, Native Americans relied more on yearly payments and manufactured goods, and there were conflicts among the tribes. Many tribes did not understand the American idea of land ownership.

Harrison's first treaty, the Treaty of Vincennes (1803), successfully got the Wea and Miami to recognize American ownership of the Vincennes tract. This land was between Kaskaskia and Clarksville, Indiana.

The Treaty of Grouseland (1805) was the second important treaty to expand the Indiana Territory. Harrison negotiated with the Delaware, Potawatomi, Miami, Wea, and the Eel River band at Grouseland, Harrison's home in Vincennes. Under this treaty, the tribes gave up their land in southern Indiana. This land was south of the Grouseland Line, which started at the northeast corner of the Vincennes tract and went northeast to the Greenville Treaty Line. Settlers, like Squire Boone, moved into this new land. They established new towns, including Corydon, Indiana (the future territorial capital) in 1808, and Madison, Indiana in 1809.

Under the Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809), Harrison bought about 2.5 million acres (10,000 km²) of land. This land is now part of Illinois and Indiana, and was bought from the Miami. The Shawnee, who were not part of the talks, lived on the western part of this land. They were angry about the treaty, but Harrison refused to cancel it. In August 1810, Harrison and the Shawnee leader Tecumseh met at Grouseland to discuss the ongoing conflict. Tecumseh strongly complained about the land given to the government. He said, "The Great Spirit has given them as common property to all the Indians, and that they could not, nor should not be sold without the consent of all." The meeting ended without a solution, as did another meeting in 1811. This disagreement led to a war called Tecumseh's War. The Native American alliance was finally defeated at the Battle of the Thames in Ontario, Canada, where Tecumseh was killed in 1813.

The War of 1812 and later treaties ended the Native Americans' armed resistance to losing their lands. Although the Miami, Delaware, and Potawatomi stayed in Indiana, most of the Wea band and the Kickapoo moved west to Illinois and Missouri. The U.S. government began to change its policy. Instead of living alongside Native Americans, they focused on taking more land. This was the first sign of an official plan to move tribes west, beyond the Mississippi River.

Treaties After Indiana Became a State

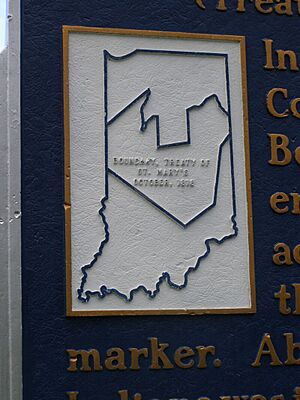

In 1818, Jonathan Jennings, Indiana's first governor, along with Lewis Cass and Benjamin Parke, negotiated several agreements. These were known as the Treaty of St. Mary's. They were made with the Miami, Wea, Delaware, Potawatomi, and other tribes. These treaties gave up land in central Indiana and Ohio to the U.S. government. The treaty with the Miami acquired most of their land south of the Wabash River. The only exception was the Big Miami Reserve in north-central Indiana, between the Eel River and the Salamonie River. Parts of these lands were given to individual Miami tribe members. These personal land grants helped protect many Miami, especially their leaders, from being removed in 1846.

The Miami were on good terms with the state because they had opposed Tecumseh and tried to stay neutral during the War of 1812. Under the treaty, the Miami also accepted a treaty made with the Kickapoo in 1809. This led to the Kickapoo's removal from Indiana. The Wea, who lived near Lafayette, Indiana, agreed to receive $3,000 yearly for giving up their land in Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois.

Under the Treaty of St. Mary's, the Lenape (Delaware) tribe, who lived in central Indiana near Indianapolis, gave up their lands to the government. This opened the area for more settlers. They agreed to leave Indiana and settle on lands provided for them west of the Mississippi River. In return for leaving, the Lenape received gifts and yearly payments totaling $15,500. Most of the tribe left for the West in August and September 1820. The Potawatomi received yearly payments for giving up some of their Indiana land. Several tribal members were given individual grants of reservation land. Most of the Potawatomi did not leave the state until 1838.

After years of peace following the War of 1812 and the land cessions from the Treaty of St. Mary's, Indiana's state government tried a more peaceful approach. They planned to "civilize" Native Americans rather than remove them. Using federal money, several mission schools were opened to educate the tribes and promote Christianity. However, these missions were not very successful.

Land cessions began again in 1819. On August 30, Benjamin Parke finished talks with the Kickapoo. They gave up their land in Indiana, including most of Vermillion County, Indiana, for goods worth $3,000 and a ten-year yearly payment of $2,000 in silver. The Miami did not recognize this treaty, as they claimed the Kickapoos' land. But European-American pioneers continued to settle in the area.

Other agreements with the Wea, Potawatomi, Miami, Delaware, and Kickapoo were made in 1819. The tribes were invited to a meeting to set up a trade agreement. Trading with Native Americans was one of the most profitable businesses in the state. In exchange for treaty agreements, the Wea received a $3,000 yearly payment. The Potawatomi received $2,500, the Delaware $4,000, and the Miami $15,000. Smaller amounts went to other tribes. These yearly payments came with extra gifts for tribal leaders, often worth similar amounts. Tribes also agreed to annual meetings at trading grounds near Fort Wayne, Indiana. There, the yearly payments would be made, and tribes could sell their goods to traders. This yearly event was the most important trading activity in the state from 1820 until 1840. Traders would gather and offer goods to the tribes, often at high prices and on credit. After the tribes approved the bills, traders would take them to the Indian agent, who would pay the claims from the tribe's yearly funds. Many leading politicians in the state, including Jonathan Jennings and John W. Davis, actively participated in this trade and made significant profits.

In exchange for giving up land to the government, Native Americans usually received yearly payments in cash and goods. They also got agreements to pay tribal debts. Sometimes, tribes were given reservation lands for their use, salt, small items, and other gifts. Treaty rules that gave land to individuals and families, and funds for fences, tools, and livestock, were meant to help Native Americans become farmers. Some treaties also provided help with clearing land, building mills, and providing blacksmiths, teachers, and schools.

The 1821 Treaty of Chicago concluded talks between the government and the Michigan Potawatomi. They gave up a narrow strip of Indiana land along the southern tip of Lake Michigan. This land extended east of the St. Joseph River, near South Bend, Indiana, along with other lands in Illinois and the Michigan Territory. In this treaty, the government also said it planned to build an east-west road connecting Chicago, Detroit, and Fort Wayne.

The Treaty of Mississinewas (1826) with the Miami and Potawatomi included most of what was left of the Miami reservation lands in northeastern Indiana and northwestern Ohio. It confined the Miami to their reservations along the Wabash, Mississinewa, and Eel rivers. This included land they had kept under the Treaty of St. Mary's. During treaty talks, Lewis Cass explained the government's reason for moving Native Americans: "You have a large tract of land here, which is of no service to you. You do not cultivate it, and there is but little game on it.... Your father owns a large country west of the Mississippi. He is anxious that his red children should remove there."

The land cessions opened up the first public lands for settlement in northern Indiana. This led to the development of South Bend and Michigan City, Indiana. It included much of LaPorte County, Indiana, and parts of Porter County, Indiana and Lake County, Indiana. The treaty with the Potawatomi also arranged for the purchase of a narrow strip of land where the government would build the Michigan Road from Lake Michigan to the Ohio River. In exchange for Indiana land north of the Wabash River (except for some reserved lands that allowed them to stay), the Miami agreed to receive livestock, goods, and yearly payments. The Potawatomi received yearly payments in cash and goods, and money from the government to build a mill and hire a miller and blacksmith, among other things. The government also agreed to pay tribal debts. Treaties with the Potawatomi were renegotiated in October 1832. The tribe was given larger yearly payments in cash and goods, totaling $365,729.87. Land was also set aside west of the Mississippi River (in present-day Kansas and Missouri) for the tribe's relocation.

Forced Removals

Although the Delaware, Piankashaw, Kickapoo, Wea, and Shawnee tribes moved in the 1820s and 1830s, the Miami and Potawatomi removals in the 1830s and 1840s were more gradual and not fully completed. By 1840, the Miami were the only "intact tribe wholly within Indiana." Even though the Miami agreed to move in 1840, their tribal leaders delayed the process for several years. Most, but not all, of the remaining Miami left in 1846.

The removal of Indiana's Native Americans did not start right after the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830. However, the Black Hawk War in nearby Illinois in 1832 brought back fears of violence between Indiana's settlers and local tribes. Other factors also increased the pressure for removal. New roads and canals passed through Native American lands in Indiana. This made it easier for settlers to reach northern Indiana. White settlers also argued that the native tribes had refused earlier attempts to adapt to "civilized society." They suggested that moving west would allow them to progress at their own pace, away from some negative changes in their lives.

Organized efforts to remove native tribes from the state began in 1832. In July, the state's Indian Services Bureau was reorganized. Money was set aside to hold talks with tribal leaders and offer them reasons to leave Indiana for lands in the West. The rising tensions after the Black Hawk War had also worried the tribes. By the 1830s, white settlers greatly outnumbered the native tribes still living in Indiana. Some, but not all, tribal leaders thought resistance would be useless. They encouraged their people to accept the best deal for their lands while they could still negotiate. Other tribes did not want to leave their lands in Indiana and refused to cooperate.

Not everyone in Indiana wanted the Native Americans to leave. However, most of their reasons were about money. Towns near the reservation lands depended on the tribes' yearly payments as a source of income, especially the Indian traders. A few traders were also land speculators. They bought the given-up Native American lands from the government and sold them to pioneer settlers, making a lot of money. Also, land treaties often included rules for paying off Native American debts to the traders.

In theory, removals were supposed to be voluntary. But negotiators put a lot of pressure on tribal leaders to accept relocation agreements. The Congress, under President Andrew Jackson's administration, gave federal power through the Indian Removal Act. This allowed them to negotiate with native tribes in eastern states. They offered land west of the Mississippi River in exchange for lands in the established states. In a series of treaties from 1832 to 1840, tribal leaders gave up many pieces of land in Indiana to the government. According to Indian agent John Tipton, between five and six thousand Native American "tribesmen" lived in Indiana in 1831. About 1,200 of them were Miami, and the rest were Potawatomi. The Potawatomi owned about three million acres in north-central and northwestern Indiana. The Miami held the Big Miami Reserve, which was thirty-four square miles near the Wabash River, and other smaller pieces of land totaling over nine thousand acres.

The Vermillion Kickapoo and some of the Potawatomi, led by Kennekuk, the Kickapoo Prophet, moved in 1832. The forced removal of the Potawatomi, known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death, happened in 1838. The Miami gave up all but a small part of their remaining land in Indiana in treaty talks in 1838 and 1840. A small Miami reservation along the Mississinewa River, in southern Wabash County, Indiana and northern Grant County, Indiana counties, and scattered land grants to individuals were the only lands the Miami kept after 1840.

Potawatomi Removals

In the 1830s, government agents began visiting Potawatomi communities in northern Indiana. They offered yearly payments, goods, payment of tribal debts, and reservation land in the West, among other things. This was in exchange for their land in Indiana. Most of the Potawatomi accepted these terms, including the government's agreement to pay for their move to new homes. Similar negotiations with tribes in other states had similar results.

The Treaty of Tippecanoe (1832) was a series of three treaties made with the Potawatomi in October 1832. These treaties gave up Native American land in Indiana, Illinois, and part of Michigan to the government. Only small reservation lands for tribal use and scattered land grants to individuals were kept. Under these treaties, the government gained over four million acres of Potawatomi land in northeastern Indiana. In return, the Potawatomi received yearly payments worth $880,000, goods worth $247,000, and payment of tribal debts totaling $111,879. The total value of these three treaties was over $1.2 million (about thirty cents per acre). Fourteen more treaties made in 1834, 1836, and 1837 gave up additional pieces of Indiana land. In exchange, the Potawatomi received payments in cash and goods amounting to $105,440. The government also agreed to set aside reservation land west of the Mississippi River, in present-day Kansas and Missouri. This reduced the Potawatomi's land in Indiana to a piece of reservation land along the Yellow River. In 1836 alone, the government negotiated nine more treaties with the Potawatomi to give up the remaining Potawatomi land in Indiana. These treaties required the Potawatomi to leave Indiana within two years.

The Treaty of Yellow River (1836) was one of Indiana's more difficult treaties. It offered the Potawatomi $14,080 for two sections of Indiana land. However, Chief Menominee and seventeen others refused to accept the terms. The Yellow River band of Potawatomi, living near Twin Lakes, Indiana, led by Chief Menominee, refused to take part in the talks. They did not recognize the treaty's power over their band. Under the treaties made in 1836, the Potawatomi were required to leave their land in Indiana within two years, including the Yellow River band. Menominee refused, saying: "I have not signed any treaty, and will not sign any. I am not going to leave my land, and I do not want to hear anything more about it." Father Deseille, the Catholic missionary at Twin Lakes, also said the Yellow River Treaty (1836) was a fraud. Colonel Pepper, the government's treaty negotiator, believed Father Deseille was interfering with their plans to remove the Potawatomi from Indiana. He ordered the priest to leave the mission at Twin Lakes or face legal action. The government refused Menominee's demands, and the chief and his band were forced to leave the state in 1838.

Indiana governor David Wallace authorized General John Tipton to forcefully remove the Potawatomi. This event became known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death, the largest single Native American removal in the state. Starting on September 4, 1838, a group of 859 Potawatomi were forced to march from Twin Lakes to Osawatomie, Kansas. The difficult journey of about 660 miles (1,060 km), in hot, dry weather and without enough food or water, led to the death of 42 people, including 28 children.

Later treaties with other Potawatomi tribes gave up more lands in Indiana, and removals continued. In a treaty made on September 23, 1836, the government agreed to buy forty-two sections of their Indiana land for $33,600 (or $1.25 per acre, the lowest price the government could get from selling public lands). A treaty made with the Potawatomi on February 11, 1837, provided for more land cessions in Indiana. In exchange, they received a piece of reservation land for tribal members on the Osage River, southwest of the Missouri River in present-day Kansas, and other guarantees. Another small group of Potawatomi from Indiana moved in 1850. Those who had been forcefully removed were first moved to reservation land in eastern Kansas. But they moved to another reservation in the Kansas River valley after 1846. Not all the Potawatomi from Indiana moved to Kansas. A small group joined about 2,500 Potawatomi in Canada.

Miami Removals

Under the terms of treaties negotiated in 1834, 1838, and 1840, the Miami gave up more land in Indiana to the government. This included parts of the Big Miami Reserve along the Wabash River. In the treaty agreement made in 1838, the Miami gave up a large part of their reservation land in Indiana. In return, they received yearly payments, cash payments to tribal leaders Jean Baptiste Richardville and Francis Godfroy, payment of tribal debts, and other benefits. Under the Treaty of the Wabash (1840), another large piece of the Miami Reservation was given to the government for $550,000. This included yearly payments, payment of tribal debts, and other provisions. The Miami also agreed to move to lands set aside for them west of the Mississippi River.

Land given to individuals under the treaties with the Miami allowed some tribe members to stay on the land as private landowners. This was under the terms of the Treaty of St. Mary's. Individuals also received more land in later treaties. Land given to tribal leaders and others was meant to encourage the European idea of land ownership. In five treaties negotiated with the Miami between 1818 and 1840, Jean Baptist Richardville received 44 quarter sections of Indiana land in separate grants. Francis Godfroy received 17 sections.

The remaining Miami reservation land was given to the government in 1846. The main removal of the Miami from Indiana began on October 6, 1846. The group left Peru, Indiana, and traveled by canal boat and steamboat to reach their reservation lands in Kansas on November 9, 1846. Six deaths occurred along the way, and 323 tribal members made it to the Kansas reservation. A small group moved in 1847. In total, less than half of the Miami moved from Indiana. More than half of the tribe either returned to Indiana from the West or were never required to leave under the terms of the treaties.

Life After Removal

Native American lands given to the government were sold to new owners—settlers and land speculators. Over three million acres of the given-up lands in Indiana were sold in 1836 alone. The financial panic of 1837 slowed the land rush, but it did not stop it. Squatters also hoped to claim a portion of the former Native American land. Under the rules of the Preemption Act (1838), squatters who were heads of families and single men aged twenty-one or older could claim up to 160 acres. This right was later extended to widows.

Native Americans who stayed in Indiana after the 1840s eventually blended into the larger culture. However, some kept ties to their Native American heritage. Some groups chose to live together in small communities, which still exist today. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, other Native American groups moved to Indiana, many of them Cherokee. The Miami Nation of Indiana is mostly found along the Wabash River. Other Native Americans settled in Indiana's cities, such as Indianapolis, Elkhart, Fort Wayne, and Evansville. In 2000, Indiana's population included over 39,000 Native Americans from more than 150 tribes.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |