Jonathan Jennings facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jonathan Jennings

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Indiana's 1st district |

|

| In office March 3, 1823 – March 3, 1831 |

|

| Preceded by | Himself (at-large district) |

| Succeeded by | John Carr |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Indiana's at-large district |

|

| In office December 2, 1822 – March 3, 1823 |

|

| Preceded by | William Hendricks |

| Succeeded by | Himself (1st district) |

| Governor of Indiana | |

| In office November 7, 1816 – September 12, 1822 |

|

| Lieutenant | Christopher Harrison Ratliff Boon |

| Preceded by | Thomas Posey (Indiana Territory) |

| Succeeded by | Ratliff Boon |

| Delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives from the Indiana Territory's at-large district |

|

| In office November 27, 1809 – December 11, 1816 |

|

| Preceded by | Jesse B. Thomas |

| Succeeded by | William Hendricks (Representative) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 27, 1784 Readington, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | July 26, 1834 (aged 50) Charlestown, Indiana, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouses | Ann Gilmore Hay Clarissa Barbee |

| Signature |  |

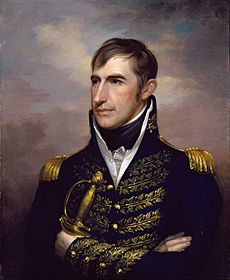

Jonathan Jennings (born March 27, 1784 – died July 26, 1834) was an important leader in Indiana's early history. He became the first governor of Indiana and also served many terms as a congressman. Jennings was born in either New Jersey or Virginia. He studied law before moving to the Indiana Territory in 1806.

Jennings first planned to be a lawyer. However, he took jobs at the federal land office and with the territorial legislature to support himself. He also became interested in buying and selling land, and in politics. Jennings got into a disagreement with the territorial governor, William Henry Harrison. This led him to enter politics and shaped his early career. In 1808, Jennings moved to eastern Indiana Territory, near Charlestown.

He was elected as the Indiana Territory's representative to the U.S. Congress. He won by getting support from those who opposed Governor Harrison. By 1812, Jennings was a leader of the group that wanted to ban slavery and make Indiana a state. He and his allies gained control of the territorial assembly after Governor Harrison resigned in 1812. As a delegate in Congress, Jennings helped pass the Enabling Act in 1816. This law allowed Indiana to form its own state government and constitution.

He was chosen to lead the Indiana constitutional convention in Corydon in June 1816. There, he helped write the state's first constitution. Jennings strongly supported banning slavery in Indiana. He also wanted the state's legislative branch (the lawmakers) to have a lot of power.

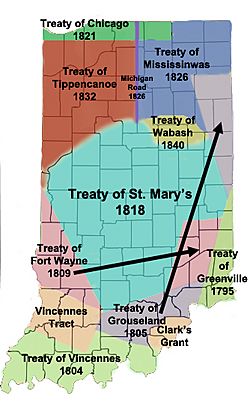

In August 1816, Jennings was elected as Indiana's first governor at age 32. He was re-elected for another term. As governor, he pushed for building roads and schools. He also helped negotiate the Treaty of St. Mary's. This treaty opened up central Indiana for American settlers. Some opponents tried to remove him from office because of his role in the treaty. They said it was against the constitution. However, this effort failed.

During his second term, Jennings faced money problems, especially after the panic of 1819. It was hard for him to manage his personal business and run the state at the same time. The state constitution did not allow him to serve another term as governor. So, Jennings looked for other ways to earn money. Before his second term ended in 1822, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. He retired from public service in 1831. In Congress, Jennings supported federal money for projects like roads and canals.

After retiring, he struggled to manage his farm. When his money situation worsened, his lenders tried to take his land. To help his friend, U.S. Senator John Tipton bought Jennings's farm. He allowed Jennings to continue living there. After Jennings died, his property was sold. There was not enough money left to buy a headstone for his grave. His grave remained unmarked for 57 years.

Historians have different ideas about Jennings's life and his impact on Indiana. Early historians praised him for defeating pro-slavery groups and setting up the state. Later historians were more critical, describing him as a clever politician who focused on himself. Modern historians place his importance somewhere in the middle. They agree that Indiana owes him a lot.

Contents

Early Life and Political Beginnings

Family and Education

Jonathan Jennings was born on March 27, 1784. His parents were Jacob and Mary Kennedy Jennings. He was the sixth of their eight children. His father was a doctor and a minister. His mother was also well-educated and helped her husband with his medical practice. Around 1790, Jennings's family moved to Pennsylvania. After his mother died in 1792, his older sister, Sarah, and brother, Ebenezer, raised him.

Jennings was schooled at home and then attended a grammar school in Pennsylvania. Two of his classmates, William Hendricks and William W. Wick, later became his political allies. Jennings studied law in Washington, Pennsylvania. By 1806, he had moved to Ohio, where his brother, Obadiah, had a law office. Jennings helped his brother with legal cases.

In 1806, Jennings moved west to the Indiana Territory. He first went to Jeffersonville, but only stayed a short time. In early 1807, he moved to Vincennes, which was the capital of the Indiana Territory. He opened his own law practice there. However, he found it hard to make money as a lawyer because there were not many clients. In July 1807, a friend offered Jennings a job as an assistant at the federal land office in Vincennes. Jennings also bought and sold land, making good profits. In 1807, he became an assistant to the clerk of the territorial legislature.

Disagreements with Governor Harrison

In August 1807, Jennings was appointed clerk of the Vincennes University board. This led him into political disagreements in the territory. The territorial governor, William Henry Harrison, was a powerful figure. He made many political appointments and had veto power. Jennings's appointment came after a dispute where Harrison wanted to ban French residents from using the university's common land. The board voted against Harrison's idea.

Jennings further angered Harrison when he tried to get a clerk position in the territorial legislature. Jennings's opponent for the job was Davis Floyd, who was against slavery and an enemy of Harrison. Jennings later dropped out of the race, and Floyd got the position. Floyd then became an important political friend to Jennings. In April 1808, a committee investigated Jennings's actions. This led to Jennings resigning in 1808. It also created a strong dislike between Jennings and Harrison that lasted for many years.

By March 1808, Jennings felt his future was limited in the western part of the territory, which Harrison controlled. By November, he had moved to Charlestown in Clark County. Jennings likely believed he would have more political success in the eastern part of the territory. Settlements in the east were against slavery and Harrison's style of leadership. This matched Jennings's own beliefs. The western part of the territory, including Vincennes, supported slavery.

In 1807, Harrison and his supporters tried to allow slavery in the territory. Jennings and his supporters wrote articles in the Vincennes Western Sun newspaper. They criticized Harrison's government, its support for slavery, and its aristocratic ways.

In 1808, Congressman Benjamin Parke resigned. Harrison ordered a special election to fill the spot. Jennings ran against Harrison's candidate, Thomas Randolph, and John Johnson, who was supported by the anti-slavery group. Jennings, who was against slavery, traveled from settlement to settlement. He gave speeches against slavery and criticized Randolph's ties to Harrison. Jennings found his strongest support among the growing Quaker community in the eastern part of the territory.

On November 27, 1809, Jennings was elected as a delegate to the Eleventh Congress. It was a close election. Randolph challenged the results, claiming some votes were not counted correctly. He went to Washington D.C. to argue his case. A House committee agreed with Randolph and suggested a new election. However, the full House voted against the committee's idea, and Jennings was allowed to take his seat. As a territorial delegate, Jennings learned how laws were made. He worked on committees, introduced bills, and continued his efforts against Governor Harrison. He was re-elected in 1811, 1812, and 1814.

Marriage and Family Life

During his first time in Congress, Jennings had a small portrait made of himself. He gave it to Ann Gilmore Hay, whom he was dating. Ann was born in Kentucky in 1792. Her family moved to Charlestown, Indiana Territory. Jennings first met her while campaigning in 1809. After his first session in Congress, Jennings returned to Indiana Territory. He married Ann, who was eighteen, on August 8, 1811. Ann's father had recently died, leaving her without family support.

After Jennings was re-elected in 1811, the couple went to Washington. Ann stayed there briefly before going to live with Jennings's sister in Pennsylvania. Jennings's wife had poor health. Her health worsened after he became governor in 1816. She died in 1826 after a long illness. Later that year, Jennings married Clarissa Barbee. She was a teacher from Kentucky. Jennings did not have any children from either marriage.

Serving in Congress

Challenges with Governor Harrison

After losing the election, Randolph continued to criticize Jennings. He even challenged Jennings to a duel, but Jennings refused. Jennings focused on the issue of slavery in his re-election campaign in 1810. He connected Randolph to Harrison's ongoing attempts to allow slavery. In 1809, Illinois was separated from the Indiana Territory. This weakened Harrison's power. Jennings's victory over Randolph in 1810 showed that people did not support Harrison's pro-slavery policies. After this election, Jennings and his anti-slavery allies passed laws that limited the governor's power.

In his first full term in Congress, Jennings increased his criticism of Harrison. He accused Harrison of using his office for personal gain and of causing problems with Native American tribes. Jennings proposed a resolution in Congress to reduce Harrison's power to make political appointments. He also opposed Harrison's policy of buying land from the Native Americans. When Harrison was up for re-appointment as governor in 1810, Jennings sent a strong letter to President James Madison arguing against it. However, Harrison's friends in Washington helped him get re-appointed.

Fighting broke out between Americans and Native American tribes, leading to the Battle of Tippecanoe in November 1811. Jennings helped pass a bill to pay veterans of the battle. It also provided pensions for the widows and orphans of those who died. Jennings felt sad about the battle. His friends in the territory blamed Harrison for causing the conflict. As calls for war with Great Britain grew, Jennings accepted the start of the War of 1812. Early in the war, Harrison became a military general and resigned as governor in 1812.

Before Harrison resigned, Jennings and his allies worked to weaken the governor's power. In 1811, the territorial legislature voted to move the capital away from Vincennes, which was a Harrison stronghold. This shifted political power from the governor to the elected members of the legislature. John Gibson, the acting governor, did not challenge the legislature. When Harrison's replacement, Thomas Posey, was confirmed in 1813, Jennings's group in the legislature was strong. They began to push for Indiana to become a state.

Jennings ran for re-election to Congress in 1811 against another pro-slavery candidate, Waller Taylor. This was Jennings's most difficult campaign. Taylor called Jennings a "coward" and challenged him to a duel, but Jennings refused. Jennings again focused on the slavery issue, using the motto, "No slavery in Indiana." Jennings easily won re-election. During his third term, Jennings began to argue for Indiana to become a state. He waited until the end of the War of 1812 to formally introduce the idea. Jennings easily won re-election in 1814 against Elijah Sparks.

Working for Statehood

By 1815, Jennings and the territorial legislature were ready to push for statehood. In December 1815, Jennings presented a request from the legislature to Congress for Indiana to become a state. A census in 1815 showed the territory had over 63,000 people. This was more than the minimum needed for statehood under the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. The House debated the issue and passed the Enabling Act on April 11, 1816. This act allowed Indiana to form a government and elect delegates to a convention to create a state constitution.

The territorial governor, Thomas Posey, worried that the territory did not have enough people to pay for a state government. He asked President Madison to veto the bill and delay statehood. However, Madison signed the bill, ignoring Posey's request.

Dennis Pennington, a key member of the territorial legislature, helped elect many anti-slavery delegates to the constitutional convention. Jennings was a delegate from Clark County. The convention was held in June 1816 in Corydon, the new territorial capital. Jennings was elected president of the assembly. This allowed him to choose the leaders of the convention's committees. The delegates wrote a new constitution for Indiana. Much of it was copied from other state constitutions, especially Ohio and Kentucky.

Some parts were new and unique to Indiana. Slavery, which was already banned in territorial laws, was also banned in the Indiana constitution. However, existing contracts for indentured servants were allowed to continue. The new state government had three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. The governor had limited powers, and most authority was given to the Indiana General Assembly and county officials. Soon after the convention, Jennings announced he would run for governor.

Governor of Indiana

First Election and Goals

At the state convention in June 1816, Jennings may have told some delegates he planned to run for governor. By early July 1816, he had publicly announced his candidacy. Thomas Posey, Indiana's last territorial governor, was Jennings's opponent. Posey was not a popular candidate and had health issues. Jennings won by a large number of votes: 5,211 to 3,934. Most of Jennings's votes came from the eastern part of the state, where he had strong support. Posey's votes likely came from the western part. Jennings moved to the new state capital at Corydon, where he served as governor.

Jennings's salary as governor was $1,000, the highest for an elected official in the state. The constitution said the governor served a three-year term and could not serve more than six years in a nine-year period. Jennings's plan included setting up courts, creating a state-funded education system, starting a state banking system, preventing the illegal capture of free Black people, organizing a state library, and planning for roads and canals. His efforts had limited success because the state had little money and the governor had limited power.

In his inauguration speech on November 7, 1816, Jennings strongly spoke against slavery. He encouraged the state legislature to pass laws to protect free Black people from being illegally taken into slavery. He also wanted to prevent those who were legally enslaved in other states from finding refuge in Indiana. In 1817, Jennings changed his stance on runaway enslaved people. He said it was needed to "preserve harmony" among the states. He agreed to allow citizens to reclaim any enslaved person who escaped to Indiana "with as little delay as possible." This was after citizens of Kentucky had trouble getting back their enslaved people who had fled to Indiana.

Improving the State

In 1818, Jennings began to promote a large plan for improving the state's infrastructure. Most projects focused on building roads, canals, and other ways to boost trade and the state's economy. During Jennings's second term, the state government continued to support public improvements. This included new road construction and more settlement in central Indiana. After Indianapolis became the permanent state capital in 1821, the Indiana General Assembly set aside $100,000 for new roads. However, this was much less than what was needed.

The state faced money shortages because of low tax revenues. This forced Jennings to find other ways to pay for projects. The main sources of money came from selling government bonds to the state bank and selling public lands. The state's spending and borrowing led to short-term money problems. Despite early difficulties, the improvements started by Jennings attracted new settlers to the state. In 1810, the Indiana Territory had 24,520 people. After Jennings's time as governor, Indiana's population grew from 65,000 in 1816 to 147,178 in 1820. By 1850, it had more than a million people.

In his first speech as governor in August 1816, Jennings talked about the need for an education plan. In his 1817 message to the state legislature, he encouraged setting up a free, state-funded education system, as the constitution called for. However, few citizens wanted to pay taxes for public schools. The state legislature believed that building government infrastructure should be the priority. Lack of public funds delayed the creation of a state library system until 1826.

From the start, the state's banks were closely tied to the government's money matters. This was made harder by the state's small economy and population, the economic downturn of the late 1810s and early 1820s, and a lack of banking experience. In 1817, Jennings signed a law to create the First State Bank of Indiana. The Bank of Vincennes, which started in 1814, became the new bank's main office. Three new branches were set up in Corydon, Brookville, and Vevay. The First State Bank soon became a place for federal money and was involved in land speculation.

When state spending was more than its income, Jennings preferred to get loans from the bank to cover the difference. Although taxes were collected and the state borrowed from the First State Bank, the state's money situation remained difficult. This was made worse by the economic downturn of 1819. By 1821, the bank was unable to pay its debts. In June 1822, a court declared the First State Bank had lost its right to operate. In November 1823, the Indiana Supreme Court agreed. The court found that the bank had mismanaged federal deposits, printed too much paper money, had too much debt, and paid large amounts to its owners. For several years after the bank's failure, Indiana citizens used other banks for financial services. Jennings was criticized for not watching the state's banks more closely.

Most of Jennings's second term was spent dealing with the state's ongoing money problems. When tax revenues and land sales remained low, the state did not have enough money to repay its loans for improvements. The Indiana General Assembly had to greatly reduce the value of its loans. This hurt the state's credit and made it hard to get new loans.

During his time as governor, Jennings nominated three judges to the Indiana Supreme Court: John Johnson, James Scott, and Jesse Lynch Holman. All three were quickly approved by the state legislature.

The Treaty of St. Mary's

In late 1818, Jennings was chosen as a federal commissioner. He worked with Lewis Cass and Benjamin Parke to negotiate a treaty with Native American tribes (Potawatomi, Wea, Miami, and Delaware) in northern and central Indiana. The Treaty of St. Mary's allowed Indiana to buy millions of acres of land. This opened most of central Indiana for American settlement.

This appointment caused a problem for Jennings's political career. The state constitution said a person could not hold a federal government job while also being the state's governor. Jennings's political enemies used this to try and remove him from office. They argued that he had left the governor's office when he accepted the federal job.

Lieutenant Governor Christopher Harrison claimed that Jennings had "abandoned" his elected office. Harrison took over as the state's acting governor while Jennings was away. Meanwhile, the Indiana House of Representatives started an investigation. When Jennings found out, he was upset that his actions were being questioned. He burned the documents he received from the federal government about his assignment. The legislature asked Jennings and Harrison to appear for questioning. Jennings refused, saying the assembly did not have the right to question him. Harrison also refused unless the assembly recognized him as the acting governor.

Since neither man would meet with the legislature, the assembly demanded copies of the documents Jennings received from the federal government. They wanted proof that he was not acting as a federal agent. Jennings replied that he acted to help the state by adding "a large and fertile tract of country."

The legislature questioned everyone who knew about the events at Saint Mary's. However, no one was sure of Jennings's exact role. After a short debate, the House voted 15 to 13 to recognize Jennings as governor. They dropped the proceedings against him. The votes against Jennings mostly came from the state's western counties. Harrison was very angry about the decision and resigned as lieutenant governor.

In 1820, Harrison ran against Jennings for re-election. Jennings won by a large margin: 11,256 votes to Harrison's 2,008. Jennings's big win showed he was still a popular politician. Voters were not overly concerned by the attacks on his character.

Financial Challenges

Jennings's personal money situation suffered from the economic downturn of 1819. Being governor also added to his financial burdens. He was never able to fully recover from his debts. One historian suggests his money problems might have come from campaign costs, his long time in government, and being too busy to manage his farm well. Jennings and his wife often hosted visitors, lawmakers, and other important people at their home in Corydon. In 1819, he hosted President James Monroe and General Andrew Jackson at a dinner in Jeffersonville. In 1822, Jennings asked for a personal loan from the Harmonists, but his request was denied. He was able to get personal loans from friends by putting his land up as collateral. Earlier in his career, when land prices dropped, he had to sell some land at a loss.

By the late 1820s, Jennings was very short on cash. He relied on his income from political office to pay his bills. His farm was not providing enough money. The law prevented the 38-year-old Jennings from running for a third term as governor in 1823. So, he had to consider other political options. Jennings decided to return to Congress.

Return to Congress and Later Career

In September 1822, just before his second term as governor ended, Jennings became a candidate for Congress. This happened after William Hendricks resigned his seat to run for Indiana governor. A special election was held on August 5, 1822, to fill Hendricks's empty seat. At the same time, Indiana's population had grown, giving the state three congressional seats. A regular election was held on the same day to elect three congressmen. Jennings won the special election against Davis Floyd. In the regular election for Indiana's Second Congressional District, Jennings easily won. He defeated James Scott by a large margin. Jennings became a Democratic-Republican in the 17th Congress. Lieutenant Governor Ratliff Boon became governor after him. Hendricks ran unopposed and was elected governor to succeed Boon.

Jennings won re-election to Congress and represented Indiana's Second District until 1830. He continued to support federal funding for infrastructure improvements. He introduced laws to build more forts in the northwest and to provide federal money for projects in Indiana and Ohio. He also led the debate to use federal funds to build the Wabash and Erie Canal through Indiana. He helped secure money to survey the Wabash River. This would make it easier for steamboats to travel year-round.

In his re-election campaign for the Second District, Jennings supported tariffs (taxes on imported goods) to protect American industries and internal improvements. He promised to support the presidential candidate his voters preferred if the election went to the House. Jennings won re-election in a close race. In the presidential election of 1824, American political parties were forming around three candidates: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and Henry Clay. Jennings favored Adams, and later, Clay. However, when the election went to the House in 1825, Jennings voted with the majority and supported Jackson. But Jackson was defeated in the House, and Adams became president.

Jennings tried to advance his political career by running for the Senate twice, but he lost both times. In 1825, the Indiana General Assembly elected the state's senators. Jennings came in third on the first vote. In his second attempt, he lost to James Noble.

Jennings's wife died in 1826 after a long illness. The couple had no children. Jennings was very sad about her loss. Later that year, he married Clarissa Barbee.

While in Congress, Jennings's health continued to decline. He suffered from severe rheumatism. In 1827, plaster fell from the ceiling of his boarding room in Washington D.C., severely injuring him. His poor health limited his ability to visit his voters. However, he remained a popular politician in Indiana. In the 1826 congressional election, Jennings ran unopposed. He won re-election in 1828, defeating his opponent, John H. Thompson. During Jennings's final term in office, records show he introduced no new laws, was often absent for votes, and only gave one speech. Jennings's friends, led by Senator John Tipton, noticed his situation. They took action to prevent Jennings from being re-elected when his health became a political issue. John Carr opposed Jennings in a six-person race for the congressional seat and won the election. Tipton had arranged for others to enter the race to divide Jennings's supporters. Jennings left office on March 3, 1831.

Later Years and Legacy

Retirement and Final Years

Jennings retired with his wife, Clarissa, to his home in Charlestown. Tipton may have felt it was a mistake to force Jennings out of public service. In 1831, Tipton helped Jennings get an appointment to negotiate a treaty with Native American tribes in northern Indiana. Jennings attended the negotiations for the Treaty of Tippecanoe, but the group did not succeed. Afterward, Jennings returned to his farm, where his health steadily worsened. He was no longer able to work his farm. Without a steady income, Jennings's lenders began to try and take his property. In 1832, Tipton bought the mortgage on Jennings's farm. He also got help from a local financier, James Lanier, to buy the debts on Jennings's other properties. Tipton allowed Jennings to stay on his mortgaged farm for the rest of his life. He encouraged Lanier to do the same.

Jennings died of a heart attack on July 26, 1834, at his farm near Charlestown. He was 50 years old. Jennings was buried after a short ceremony in an unmarked grave. His estate did not have enough money to buy a headstone. Jennings's lenders, many of whom were his neighbors, were not paid. After Jennings's death, Tipton sold the Jennings farm and gave Jennings's widow a gift of $100 from the money.

Memorials and Recognition

In the late 1800s, several attempts were made to build a monument honoring Jennings. Three times, in 1861, 1869, and 1889, requests were made to the Indiana General Assembly to put a marker on Jennings's grave. Each time, the request failed. In 1893, the state legislature finally approved the request to build a monument in his honor. Around the same time, after three witnesses confirmed his unmarked gravesite, his body was moved and reburied at a new spot in the Charlestown Cemetery.

Jonathan Jennings Elementary School in Charlestown and Jennings County are both named after him. In 2016, Indiana celebrated its Bicentennial (200 years). As part of the celebration, the Indiana General Assembly named Interstate 65 through Clark County the Governor Jonathan Jennings Memorial Highway. On August 10, 2016, the 23.6-mile stretch of Interstate 65 was officially dedicated.

His Impact on Indiana

Historians have different ideas about Jennings's life and his impact on Indiana's growth. Early state historians praised Jennings. They focused on his strong leadership in Indiana's early years. One historian called him the "young Hercules," praising his fight against Harrison and slavery. Another said, "Indiana owes him a debt more than she can compute."

Later historians in the early 1900s were more critical of Jennings. One described his abilities as "average." Another argued that Jennings "took no decisive stand" on important issues. They said the legislature, not Jennings, set the tone for the era. In 1954, historians described Jennings as a "shrewd politician rather than a statesman." They said his leadership was "not evident" at the 1816 convention. However, they also noted that his personal struggles should not hide his important contributions as a territorial delegate, president of the Constitutional Convention, first state governor, and congressman.

Modern historians suggest that Jennings's legacy is "somewhere between the two extremes." They agree that Indiana owes Jennings a debt of gratitude. Even though his accomplishments were not huge, he did a "commendable" job guiding the state as it moved toward a more democratic government. One historian describes Jennings as "ambitious," "passionate," "hot-tempered," and "moody." He argues that Jennings was good at campaigning but not as good at being a statesman or governor.

Jennings believed in popular democracy. He was against slavery and disliked powerful people who he felt were "trampling on the rights of his fellow Americans." His time as Indiana's governor and representative in Congress came at a time when government power shifted. It moved from the governor and his appointments to the state legislature and elected officials.

Images for kids

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |