Abraham Fornander facts for kids

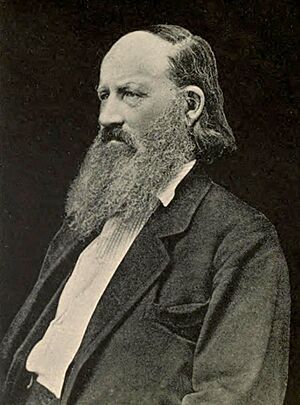

Abraham Fornander (born November 4, 1812 – died November 1, 1887) was a Swedish man who moved to Hawaii. He became a very important journalist, judge, and expert on different cultures (an ethnologist) in the Hawaiian Kingdom. He is best known for his writings about the history and origins of the Polynesian people.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Abraham Fornander was born in Öland, Sweden, on November 4, 1812. His parents were Anders and Karin Fornander. For most of his early years, his father, who was a clergyman, taught him at home.

From 1822 to 1823, Abraham studied at a school called a gymnasium in Kalmar. There, he learned important ancient languages like Latin, Greek, and Hebrew.

In 1828, he started studying theology (the study of religion) at the University of Uppsala. Two years later, in 1830, he moved to the University of Lund. However, in 1831, he left the university to help his family, who were going through a difficult time. After this, Fornander left Öland and traveled to Malmö, then Copenhagen, before sailing to America.

Life in Hawaii

Moving to the Islands

Not much is known about Abraham Fornander's life right after he arrived in America. He later wrote that he had to become a whaler (someone who hunts whales) because of his situation. He first visited the Hawaiian islands in 1838. He then went on a whaling trip that lasted until 1842.

After his time at sea, a doctor named Thomas Charles Byde Rooke hired Fornander. He worked as a coffee planter in Nuʻuanu Pali, on the island of Oahu. In 1847, Dr. Rooke hired him again, this time as a land surveyor, which means he measured and mapped land.

On January 19, 1847, Abraham Fornander became a citizen of the Kingdom of Hawaii. He promised his loyalty to King Kamehameha III. In the same year, he married Pinao Alanakapu in Honolulu. She was a Hawaiian chiefess from Molokai. They had three daughters and one son. Only one daughter, Catherine, lived to be an adult. His wife, Pinao, passed away in 1857.

Working as a Journalist

In 1849, Hawaii was thinking about changing its government. At this time, Abraham Fornander started writing for a new newspaper called the Argus. He eventually took over the paper. He used his newspaper to support good government, better public education, and other important changes.

When the Argus closed in 1855, Fornander started a new magazine called the Sandwich Islands Monthly. This magazine was meant to cover local news and discuss big ideas in science, literature, and religion. The magazine only lasted less than a year. However, a common idea in Fornander's writing was his concern for the Hawaiian people. After this, Fornander worked for The Polynesian, another newspaper, where he was the editor until it closed in 1864.

Serving as a Public Official

In late 1863, the new Hawaiian king, Kamehameha V, saw how talented Fornander was. He appointed him to the nation's privy council. This group was made up of about thirty of the most important men in the islands.

In May 1864, the King made Fornander a judge. He held this job for less than a year. Then, he became the superintendent of the Honolulu school district. In March 1865, he was made the Inspector General of Schools for the entire kingdom.

Fornander had always believed in public education. As Inspector General, he had three main goals:

- To make the school system fair for everyone, no matter their religion.

- To create more opportunities for girls to get an education.

- To improve the teaching of English.

His first goal, making schools non-religious, caused some problems with American Protestant missionaries. They thought he was being unfair. By July 1870, their strong disagreement led to Fornander being replaced as Inspector General.

However, the King re-appointed him in May 1871 to the circuit court, where he served as a judge for the next twelve years. He also served on many other government groups. These jobs required Fornander to travel a lot. This travel helped him learn more about Hawaiian mythology (ancient stories and beliefs) and the Hawaiian language.

His Big Work: Account of the Polynesian Race

While working his official jobs, Fornander was also developing his ideas about where the Hawaiian people came from. He collected a lot of information for a major book. In 1877, he finished the first part of his huge work, An Account of the Polynesian Race, its Origin and Migrations, and the Ancient History of the Hawaiian People to the Times of Kamehameha I. This book was published in London in 1878.

In this book, Fornander suggested that the Polynesians were related to people from ancient India. He believed they had traveled over many years through India and the Malay islands into the Pacific islands.

Fornander used Polynesian languages, family histories (genealogies), and myths to support his ideas. He thought that Polynesians first arrived in Fiji around the 1st or 2nd centuries AD. When they were pushed out by other groups, they moved to Samoa and Tonga. By AD 400 or 500, he believed they reached Hawaii. They lived there alone until the 11th century, when new groups started to arrive.

Fornander paid close attention to Hawaiian legends and family trees. He believed these records kept the history of the Hawaiian islands after they were settled. This included their wars, family disagreements, and later, their contact with explorers like Captain James Cook and George Vancouver. He later published more parts of his book series. The last part ended with the victory of Kamehameha I and how he united all the islands.

This important work brought Fornander attention from around the world. In 1878, he was asked to become a member of the California Academy of Science. The next year, the Hawaiian King made him a Knight Companion of the Royal Order of Kalākaua. In 1880, he was invited to join the Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography.

Later Life and Legacy

Abraham Fornander enjoyed the international praise for his work. He continued his official duties, even serving as acting governor of Maui for a time. In 1886, he began to feel pain in his mouth. It soon became clear that he had a serious illness.

Even though he was sick, he continued to travel as a circuit judge. The Hawaiian assembly voted to give him a pension (regular payment) of $1200 per month once he stopped working for the government. They also gave him a one-time payment of $2500 to help with the costs of publishing his research. His work was called "the most learned work ever written here [and] a credit to the author, to his adopted country, and to the Hawaiian people."

In November 1886, Fornander was made a Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Kamehameha I. He was the last person ever given this honor. In December, he was made a Knight of the North Star by Oscar II of Sweden, who was the King of Norway and Sweden.

On December 27, 1886, Fornander was appointed a justice of the supreme court. He officially started this job early the next year. However, his illness was too advanced for him to actually serve. He spent his final months at his only daughter's home. Abraham Fornander passed away on November 1, 1887, after a long battle with cancer.

Impact and Influence

After Abraham Fornander's death, many people praised his contributions to Hawaii. They recognized him as both a fair judge and a great scholar. The Hawaiian royal family attended his funeral. A memorial in his honor was built in Honolulu, and it still stands there today.

Fornander left his papers and library to his daughter. She later sold them to Charles Reed Bishop. This collection included over 300 books, along with many journals and scientific yearbooks. Over time, this collection became part of the Hawaiian Historical Society, where they are still kept today.

Charles Reed Bishop also bought Fornander's personal papers and many notes. He gave these to the Bernice P. Bishop Museum, which he founded in memory of his wife. These papers contained many Hawaiian chants, folktales, myths, and family histories. They were finally published as the Fornander Collection between 1916 and 1920. The collection includes Fornander's original Hawaiian writings, along with an English translation edited by Thomas George Thrum.

Images for kids

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |