Action of 22 September 1914 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Action of 22 September 1914 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First World War | |||||||

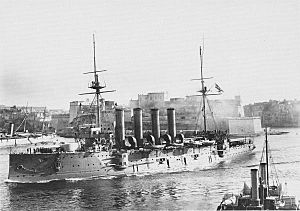

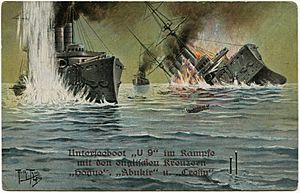

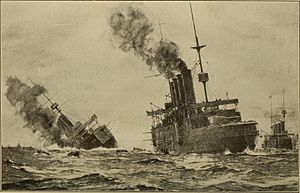

Artist's illustration of the sinking of HMS Aboukir |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1 submarine | 3 armoured cruisers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | 1,459 killed 3 armoured cruisers sunk |

||||||

The Action of 22 September 1914 was a surprise attack during World War I. A German U-boat (a submarine) called U-9 sank three British warships. These ships were older Royal Navy cruisers. They were part of the 7th Cruiser Squadron. Many of their crew were part-time sailors called reservists.

The attack happened while the ships were patrolling the southern North Sea. Nearby neutral ships and fishing boats quickly helped rescue survivors. However, 1,459 British sailors tragically lost their lives. This event caused a big shock in Britain. It made people question the government and the strength of the Royal Navy. This was especially important as many countries were still deciding which side to join in the war.

Contents

Why the Ships Were There

The British cruisers were part of a group called the Southern Force. This group included the main ship, Euryalus, and the light cruiser Amethyst. The 7th Cruiser Squadron was also part of this force. It was sometimes called the live-bait squadron. This squadron had several large armoured cruisers, including Aboukir, Hogue, and Cressy.

Their job was to patrol the North Sea. They supported smaller ships like destroyers and submarines. Their main goal was to stop the German Navy from entering the English Channel.

Old Ships, New Dangers

Even though the three ships were less than 15 years old, naval technology had changed a lot. These cruisers were not built to handle modern attacks. People had worried that these older ships were not safe against newer German warships.

However, the Navy's orders from July 1914 were still in place. These orders mainly focused on attacks from destroyers, not submarines. The ships were told to patrol an area "clear of enemy torpedo craft and destroyers." They were usually further north but moved south to help protect troop movements. This put them closer to German bases and made them more open to submarine attacks.

Before the Attack

On September 16, the admiral in charge, Arthur Christian, was allowed to keep two cruisers north. One was to stay at the Broad Fourteens. But he kept them all together in a central spot. This way, they could help in both areas.

The next day, bad weather forced the destroyer escorts to leave. The storm was so bad that the patrols could not be properly set up. The Admiralty (the British Navy's headquarters) ordered the ships to cover the Broad Fourteens until the weather improved.

On September 20, Euryalus went back to port for more coal. By September 22, Aboukir, Hogue, and Cressy were on patrol. Captain J. E. Drummond of Aboukir was in command.

At the start of the war, German U-boats had not been very successful. They had sent out ten submarines but hadn't sunk any ships. They had also lost two of their own. But on the morning of September 22, Otto Weddigen, the commander of U-9, spotted the three British cruisers.

The Attack Begins

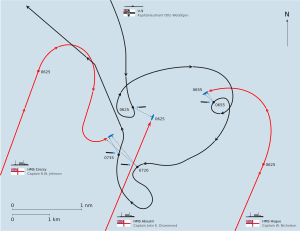

At 6:00 AM on September 22, the weather was calm. The ships were patrolling at about 10 kn (12 mph; 19 km/h) (11.5 mph or 18.5 km/h). They were sailing side-by-side, about 2 nmi (2.3 mi; 3.7 km) (2.3 miles or 3.7 km) apart. Lookouts were watching for submarine periscopes. One gun on each side of each ship was ready.

U-9 had been ordered to attack British transport ships. But the storm had forced it to dive and hide. When it surfaced, Weddigen saw the British ships and decided to attack.

At 6:20 AM, U-9 fired a torpedo at the middle ship, Aboukir. The torpedo hit the ship's right side. This flooded the engine room and stopped the ship immediately. No submarines had been seen, so Captain Drummond thought they had hit a mine. He ordered the other two cruisers to come closer and help.

Aboukir turned over after 25 minutes and sank five minutes later. Only one lifeboat could be launched. The explosion had damaged the ship, and the steam-powered winches needed to launch other lifeboats failed.

Sinking of Hogue and Cressy

U-9 had dived after firing the first torpedo. It then rose to periscope depth. Weddigen saw the other two cruisers rescuing sailors from Aboukir. He fired two torpedoes at Hogue from about 300 yd (270 m) (274 meters) away.

As the torpedoes were fired, the front of U-9 rose out of the water. Hogue's gunners saw it and fired before the submarine dived again. The two torpedoes hit Hogue. Within five minutes, Captain Wilmot Nicholson ordered everyone to leave the ship. Hogue turned over after ten minutes and sank at 7:15 AM.

Sailors on Cressy had also seen the submarine. They fired at it and tried to ram it, but failed. Then they turned to pick up survivors. At 7:20 AM, U-9 fired two torpedoes at Cressy from its back tubes. One torpedo missed. The submarine then turned and fired its last front torpedo from about 550 yd (500 m) (503 meters) away.

A torpedo hit Cressy's right side around 7:25 AM. A second one hit the left side at 7:30 AM. The ship turned over to its right side and floated upside down until 7:55 AM.

Two Dutch fishing boats nearby did not come close to Cressy. They were afraid of mines. British destroyers, led by Tyrwhitt, had received distress calls. They were already at sea and heading towards the cruisers as the weather had improved.

At 8:30 AM, a Dutch steamship named Flora arrived and rescued 286 men. Another steamer, Titan, picked up 147 men. More were saved by fishing trawlers before the destroyers arrived at 10:45 AM. In total, 837 men were rescued. But 62 officers and 1,397 men, many of them reservists, were killed. Robert Johnson, the captain of Cressy, was among the dead.

The destroyers searched for the submarine. U-9 had little battery power left to travel underwater. It could only go about 14 kn (16 mph; 26 km/h) (16 mph or 26 km/h) on the surface. The submarine submerged for the night and returned to its base the next day.

What Happened Next

This disaster greatly shocked the public in Britain and around the world. It made people lose confidence in the Royal Navy. Other cruisers were taken off patrol duties. Admiral Christian was officially criticized. Captain Drummond was also criticized for not taking precautions against submarines. However, he was praised for his actions during the attack.

The 28 officers and 258 men rescued by the Flora were taken to a port in the Netherlands. They were sent back home on September 26.

A Lucky Survivor

Wenman "Kit" Wykeham-Musgrave (1899–1989) was an amazing survivor. He was on all three ships that were torpedoed! His daughter later shared his story:

He went overboard when the Aboukir was going down and he swam like mad to get away from the suction. He was then just getting on board the Hogue and she was torpedoed. He then went and swam to the Cressy and she was also torpedoed. He eventually found a bit of driftwood, became unconscious and was eventually picked up by a Dutch trawler.

—Pru Bailey-Hamilton

Wykeham-Musgrave survived the war. He rejoined the Royal Navy in 1939 and became a commander.

Heroes and Lessons Learned

Otto Weddigen and his crew returned home to a hero's welcome. Weddigen received the Iron Cross, 1st Class, a high military award. His crew each received the Iron Cross, 2nd Class.

The sinking of the three ships made the British Admiralty take the danger of U-boat attacks much more seriously. Commander Dudley Pound, who later became the head of the Royal Navy, wrote in his diary:

Much as one regrets the loss of life one cannot help thinking that it is a useful warning to us — we had almost begun to consider the German submarines as no good and our awakening which had to come sooner or later and it might have been accompanied by the loss of some of our Battle Fleet.

—Pound

This meant that even though the loss of life was sad, it taught the Navy a valuable lesson. They had started to think German submarines were not a big threat. This event showed them they were wrong.

In 1954, the British government sold the rights to salvage (recover items from) the sunken ships. Work to recover things from the wrecks began in 2011.

Order of Battle

This lists the main ships involved in the battle.

- HMS Aboukir, armoured cruiser (main ship)

- HMS Hogue, armoured cruiser

- HMS Cressy, armoured cruiser

- U-9, submarine